The Impact of Health Insurance on the Wellbeing of Older Chinese

Using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2011, 2013 and 2015, we analyze whether the universal health insurance system in China increases the life satisfaction of middle-aged and older adults and to what extent the type of health insurance affects their life satisfaction. We find that the life satisfaction of middle-aged and older adults does not depend on having any health insurance coverage but varies with the type of health insurance coverage, controlling for potential confounding variables such as health status, occupation, and other demographic variables. Individuals covered by the most generous program, the Government Medical Insurance (GMI), reported a higher life satisfaction while those covered by the Urban Employee Medical Insurance (UEMI), the Urban Resident Medical Insurance (URMI), and the New Rural Cooperative Scheme (NCMS) reported lower life satisfaction, which suggests that establishing a more equitable health insurance system should be the next step in health reforms in China.

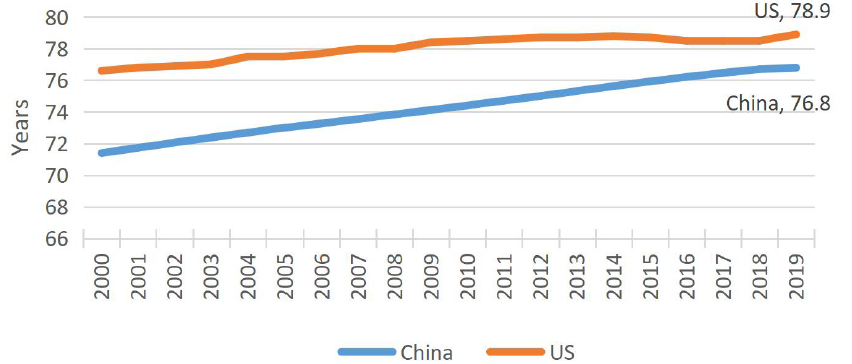

Over the past three decades, China’s population has aged faster than that of most other countries. Life expectancy at birth increased to 76.8 years in 2019, just two years less than life expectancy in the U.S. (Figure 1). The proportion of the population aged 60 years and above was 18 percent in 2018 and is projected to increase to 34 percent by 2045 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2018). Chinese older adults now live longer and have experienced substantial economic development, but are they also happier?

Figure 1: Life expectancy at birth in China and the U.S., 2000–2019 (years)

Source: World Bank (2020)

A substantial income, good physical and mental health, and health insurance coverage are important factors for older adults pursuing a happy life (Ng et al., 2017; Gwozdz and Sousa-Poza, 2010; Qi and Zhou, 2010; Wu and Tsay, 2018). However, older adults in China have experienced health and financial risks in recent years. In 2015, 100 million older adults in China reported having at least one chronic disease. Moreover, a large proportion of older adults had no access to health care (World Health Organization, 2015). Addressing “difficult and expensive to access health care” (kanbingnan kanbinggui) has thus become an important public policy issue since the 2000s.

Since 2009, the central government has conducted a series of reforms that aim to provide universal and affordable health care for all residents. One important policy is to develop universal health insurance for the general population, especially vulnerable groups such as older adults. The Chinese government introduced the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) in 2003 for rural residents, and introduced the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI) scheme in 2007 for urban residents without formal employment, such as the elderly, students, and the self-employed.The two new schemes, combined with two existing schemes (the Government Medical Insurance, or GMI, for employees of government institutes, and the Urban Employee Medical Insurance, or UEMI, for urban employees) established universal health insurance in China (see Note 1). Older adults benefited from this universal coverage. In 2012, more than 98 percent of older adults were covered by a public health insurance program (World Health Organization, 2015).

However, there is mixed evidence on the effects of health insurance on health and subjective wellbeing in the general population, including for older adults. Several studies find that enrolment in both the NCMS and URBMI do not reduce the out-of-pocket medical expenses of enrollees, although enrollment promotes their utilization of medical services (Cheng et al., 2015; Liu and Zhao, 2014). The benefits from these programs are generally insufficient, and access to health care is often inequitable, which leads to a disparity in health outcomes across the different health insurance schemes (Su et al., 2018). However, Qi and Zhou (2010) find that Chinese older adults covered by the relatively generous GMI program have a higher self-reported subjective wellbeing compared to their counterparts. There are no longitudinal studies of how the coverage of different health insurance programs impacts the life satisfaction of older adults in China.

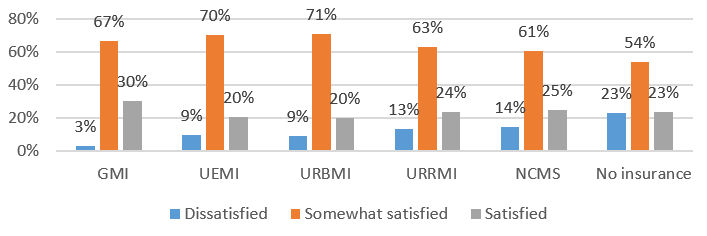

Our recent study (Yang and Hanewald, 2020) tests the extent to which having various health insurance coverage programs contributes to life satisfaction among middle-aged and older adults (age 45 and above) in China. Based on data from the nationally representative China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) survey in 2011, 2013, and 2015, we document that older adults without any health insurance coverage report the highest rates of life dissatisfaction (23 percent), while GMI enrollees report the lowest rate (3 percent), followed by URBMI enrollees (9 percent). At the same time, GMI enrollees have the highest life satisfaction rate (30 percent) compared to their counterparts (Figure 2) (see Note 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of life satisfaction by public health insurance

Source: CHARLS, 2011, 2013 and 2015

Based on a panel fixed effects model, we find that the change from no health insurance to some type of health insurance among middle-aged and older adults does not necessarily promote higher life satisfaction. Rather, it is coverage by a generous health insurance package (such as the GMI) that significantly drives higher life satisfaction. Specifically, those middle-aged and older adults who changed their health insurance coverage from the GMI to either the UEMI, the URBMI, or the NCMS reported a lower level of life satisfaction (see Note 3).

Why does health insurance coverage affect life satisfaction among middle-aged and older adults? We show that self-reported health status is a mediator between health insurance and life satisfaction. GMI enrollees are more likely to access health care and be able to cover their health care expenses. They then benefit from the program and enjoy good health, which in turn improves their life satisfaction.

Based on these findings, we offer several suggestions for further reforms to China’s health insurance system. First, it is important to recognize that the current health insurance system is fragmented. Individuals enrolled in different health insurance schemes would face different out-of-pocket expenditures for the same health care with the same quality. The central government should set up guidelines and plans to deepen the reforms of the health insurance system. While universal coverage has been generally achieved, further reforms should focus on narrowing the gaps in the levels of service provision across schemes. For example, the NCMS could be integrated into the URBMI or the UEMI, or the GMI and the UEMI could merge into one new health insurance scheme. This consolidation should aim to reduce the gaps across different schemes and provide adequate inpatient and outpatient services to all enrollees. Some provinces and cities have begun the process of consolidation (for example, Nanchang City merged the URBMI, the URRMI, and the NCMS in 2016), but the pace of consolidation varies across China. Pilot programs at the city or provincial level lack the universal standards for reimbursements and benefit packages. Further consolidation requires national and universal guidelines as well as financial support from the central government.

Second, the central government should subsidize vulnerable groups, such as economically disadvantaged older adults who have difficulty purchasing health services or high levels of demand regarding access to services. Following Japan’s model, China could design a package of services for older adults, which would provide subsidies to older adults and encourage them to use affordable health services. Our research suggests that equitable and affordable insurance is critical to reduce the disparity in health status and therefore improve the life satisfaction of older adults.

Note 1: Funding sources differ across health insurance types. The UEMI is funded by an 8 percent payroll contribution, of which employers pay 6 percent and employees pay 2 percent. The URBMI receives 70 percent of its funding from government subsidies and 30 percent from individual premiums. The NCMS is funded 80 percent by government subsidies and 20 percent by individual premiums. The GMI is 100 percent funded by the government (World Bank, 2010).

Note 2: We note that some regions or provinces in China have started to merge the NCMS and the URBMI into one scheme (the f Urban and Rural Resident Medical Insurance, or URRMI) since 2014. We found that only 2 percent respodents reported to be covered by the URRMI in our sample.

Note 3: The main reason for a change in health insurance is a change in employment status. Approximately 35 percent of respondents changed their employment status between the three waves of CHARLS. In addition, approximately 5 percent of respondents changed from the GMI to other types of insurance after their retirement. We controlled for potential confounding variables, such as employment status and retirement, in the panel fixed effects model.

[Sisi Yang, ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR); Katja Hanewald, School of Risk & Actuarial Studies, UNSW Sydney, and CEPAR]

References

Chen, Y., & Fang, H. (2018). How family planning policies reshape the life of the Chinese elderly. VoxChina. http://voxchina.org/show-3-98.html (Accessed 20 May 2020).

Cheng, L., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Shen, K., & Zeng, Y. (2015). The impact of health insurance on health outcomes and spending of the elderly: Evidence from China’s new cooperative medical scheme. Health Economics, 24(6), 672–91.

Gwozdz, W., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2010). Ageing, health, and life satisfaction of the oldest old: An analysis for Germany. Social Indicators Research, 97(3), 397–417.

Liu, H., & Zhao, Z. (2014). Does health insurance matter? Evidence from China’s urban resident basic medical insurance. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(4), 1007–20.

Keng, S. H., & Wu, S. Y. (2014). Living happily ever after? The effect of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance on the happiness of the elderly. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(4), 783–808.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2018). http://www.stats .gov.cn/tjsj/ (Accessed 14 October 2019).

Ng, S. T., Tey, N. P., & Asadullah, M. N. (2017). What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest-old? Evidence from China. PLOS One, 12(2), e0171799.

Qi, S., & Zhou, S. (2010). The influence of income, health, and Medicare insurance on the happiness of the elderly in China. Journal of Public Management, 1 (in Chinese).

Su, M., Zhou, Z., Si, Y., Wei, X., Xu, Y., Fan, X., & Chen, G. (2018). Comparing the effects of China’s three basic health insurance schemes on the equity of health-related quality of life: Using the method of coarsened exact matching. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 41.

World Bank. (2016). Live long and prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2020). Life expectancy at birth, total (years). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN (Accessed 10 June 2020).

Wu, L. H., & Tsay, R. M. (2018). The search for happiness: Work experiences and quality of life of older Taiwanese men. Social Indicators Research, 136(3), 1031–51.

Yang, S., & Hanewald, K. (2020). Life satisfaction of middle-aged and older Chinese: The role of health and health insurance. Social Indicators Research, forthcoming.

Zhang, C., Lei, X., Strauss, J., & Zhao, Y. (2017). Health insurance and health care among the mid-aged and older Chinese: Evidence from the national baseline survey of CHARLS. Health Economics, 26(4), 431–49.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email