Employment Protection and Corporate Cash Holdings: Evidence from China’s Labor Contract Law

We examine whether and how employment protection influences corporate cash holdings using Chinese firm-level data. Our empirical results show that labor-intensive firms in China significantly increased their cash holdings following the enactment of China’s Labor Contract Law. Further analyses suggest that the results are generally consistent with a “labor adjustment costs” channel: employment protection increases labor adjustment costs and hence the expected costs of financial distress for labor-intensive firms, so these firms are likely to increase their cash holdings to reduce the risk of financial distress when employment protection is strengthened.

Employment protection through various regulations on labor is widespread. Given that human capital has become an increasingly important asset for firms (Zingales 2000), it is important to study whether and how employment protection influences firms. We specifically examine its impact on corporate cash policy as it is at the core of firms’ operation. A previous study by Klasa, Maxwell, and Ortiz-Molina (2009) finds that employment protection provided by unionization reduces corporate cash reserves. Their explanation is that unionization increases the collective bargaining power of workers, so firms in more unionized industries strategically hold less cash to shelter their income from labor unions’ demands.

However, employment protection is a multidimensional concept. While the collective bargaining power of labor unions leads to a decrease in cash holdings, other institutions of employment protection may exert different impacts on cash holdings through alternative mechanisms. In particular, many measures of employment protection, including labor unions, increase firms’ labor adjustment costs. Unionization is also likely to exert a positive impact on cash holdings by increasing labor adjustment costs, but it is dominated by the negative effect through the “collective bargaining power” channel (Schmalz 2015). Theoretically, employment protection increases labor adjustment costs and hence the expected costs of financial distress for labor-intensive firms. It follows that these firms are likely to increase their cash holdings to reduce the risk of financial distress when employment protection is strengthened. Thus, a more complete account of the role played by employment protection deserves further investigation. We complement the existing literature by examining how employment protection affects corporate cash holdings through the “labor adjustment costs” channel.

In 2007, China passed the Labor Contract Law (“the LC Law” hereafter). Compared to previous labor regulations, the LC Law significantly increases employment protection and makes firing workers more costly. It does not involve a collective bargaining mechanism and allows us to isolate the labor adjustment costs channel. Furthermore, the law’s passage was not due to firms’ lobbying, and it can be considered a quasinatural experiment from the perspective of individual firms. We thus take advantage of a policy change in China to test the above hypothesis.

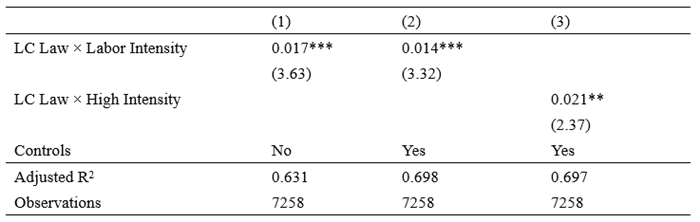

We use data of listed companies in the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges over the 2005–10 period obtained from the CSMAR database to study the influence of employment protection on corporate cash holdings. Specifically, we compare the changes in cash holdings of firms with high labor intensity (“treatment group” or “treated firms”) and those with low labor intensity (“control group” or “control firms”) before and after the enactment of the law. Labor intensity is defined as the ratio of the number of employees to total assets. As shown in Table 1, column (3), our empirical analysis suggests that the treatment group experiences a relative increase of 2.1 percentage points in cash holdings as measured by the cash to noncash assets ratio, or a 10% increase as compared to the average ratio, which is consistent with our hypothesis that employment protection increases the cash holdings of labor-intensive firms.

Table 1. Employment Protection, Labor Intensity, and Cash Holdings

Note: The dependent variable is Cash Holdings, measured as the ratio of cash and marketable securities to total noncash assets. LC Law is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the LC Law is effective and 0 otherwise. Labor Intensity is the ratio of the number of employees to total assets. High Intensity is a dummy variable that equals 1 if a firm’s labor intensity is greater than the sample median and 0 otherwise. All regressions control for firm and year fixed effects. The t statistics are in parentheses and are adjusted for heteroskedasticity and within-firm clustering. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

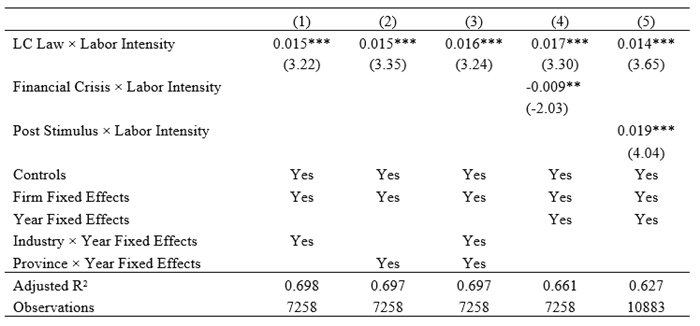

Our results could also be driven by other confounding factors. In particular, if there is a contemporaneous shock that increases the cash holdings of labor-intensive firms, our results would suffer from the omitted variables bias. We adopt a number of strategies to tackle this endogeneity concern and present the analysis in Table 2. First, we explicitly control for time-varying industrial and regional shocks by including industry-year and province-year fixed effects, and the results are qualitatively unchanged as shown in columns (1) to (3). We then consider two prominent macroeconomic shocks around the enactment of the LC Law: the global financial crisis triggered by the 2007–8 US subprime mortgage crisis and China’s four trillion RMB stimulus plan to counter the global financial crisis. Our analysis in columns (4) and (5) shows that they do not cause the main finding.

Table 2. Employment Protection, Labor Intensity, and Cash Holdings: Confounding Factors

Note: The dependent variable is Cash Holdings. LC Law and Labor Intensity are defined as in Table 1. Financial Crisis equals 1 for year 2008 and 0 otherwise. Post Stimulus equals 1 for years 2011–13 and 0 otherwise. The t statistics are in parentheses and are adjusted for heteroskedasticity and within-firm clustering. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

It is possible that the results are driven by a contemporaneous wage rise that has a larger impact on the cash holdings of labor-intensive firms. To address this concern, we conduct several cross-sectional tests to add evidence to our argument. In particular, if labor-intensive firms indeed increase cash holdings after the enactment of the law due to the increase in labor adjustment costs, such an effect should vary cross-sectionally, depending on government enforcement as well as firms’ compliance with the law and their ability to adjust cash reserves.

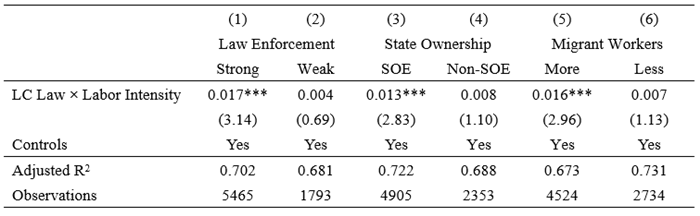

First, given the large disparity of law enforcement in different areas of China, we compare the effect of the LC Law on the cash holdings of the treatment group in areas with strong law enforcement to those with weak law enforcement. As shown in Table 3, columns (1) and (2), labor-intensive firms in the subsample with strong law enforcement increased cash holdings significantly after the enactment of the LC Law, while such an effect is not observed in the subsample with weak law enforcement. Second, a firm should be more affected by the LC Law if it is more compliant with laws. Using state ownership as a proxy for compliance with laws, as shown in Table 3, columns (3) and (4), we find that the positive impact of the LC Law on the cash holdings of labor-intensive firms appear only in the group of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) but not in the group of non-SOEs. Third, the LC Law increases employment protection more for migrant workers (temporary employees) than for formal employees, so the effect of the LC Law should be stronger for industries with a higher proportion of migrant workers, which is confirmed by the empirical analysis in Table 3, columns (5) and (6) .

Table 3. Employment Protection, Labor Intensity, and Cash Holdings: Cross-Sectional Tests

Note: The dependent variable is Cash Holdings. LC Law and Labor Intensity are defined as in Table 1. Columns (1) and (2) examine subsamples with strong and weak legal enforcement, respectively. Columns (3) and (4) examine the subsamples of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-SOEs, respectively. Columns (5) and (6) examine the subsamples of industries with the migrant worker ratio above and below the industrial median, respectively. All regressions control for firm and year fixed effects. The t statistics are in parentheses and are adjusted for heteroskedasticity and within-firm clustering. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

To further rule out the possibility that our results are driven by other confounding factors such as a concurrent wage increase, we directly test the mechanism behind our hypothesis, i.e., the LC Law makes labor adjustment costlier for firms and hence increases their operating leverage. Using the elasticity of a firm’s operating income with respect to its sales as a proxy for operating leverage, we find that operating leverage increased after the enactment of the LC Law, which is consistent with our hypothesis.

Overall, our main finding is in sharp contrast to that of Klasa, Maxwell, and Ortiz-Molina (2009). The contrast reveals that while they all aim to protect the rights of workers, different forms of employment protection may work through different mechanisms and have diverse implications for firms. It also underscores the importance of analyzing institutional details before discussing the role of employment protection.

(Chenyu Cui is currently an assistant professor of accountancy at Business School, University of International Business and Economics; Kose John is Charles William Gerstenberg Professor in Banking and Finance at the Leonard N. Stern School of Business, New York University; Jiaren Pang is an associate professor of finance at School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University; Haibin Wu is an associate professor of accountancy at College of Business, City University of Hong Kong.)

References

Klasa, Sandy, William F. Maxwell, and Hernán Ortiz-Molina. 2009. “The Strategic Use of Corporate Cash Holdings in Collective Bargaining with Labor Unions.” Journal of Financial Economics 92 (3), 421–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.07.003.

Schmalz, Martin. 2015. “Unionization, Cash, and Leverage.” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2254025.

Zingales, Luigi. 2000. “In Search of New Foundations.” Journal of Finance 55 (4): 1623–53. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.228472.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email