Gender Differences in Reactions to Failure in High-Stakes Competition: Evidence from the National College Entrance Exam Retakes

We document gender differences in reactions to failure in the National College Entrance Exam, an important, high-stakes competition that solely determines college admission outcomes for almost all teenagers in China. Using unique administrative data in Ningxia Province and a regression-discontinuity design, we find that students who score just below the tier-2 university cutoff have an eight-percentage-point higher probability of retaking the exam in the next year, and that retaking substantially improves exam performance. However, women are less likely to retake than men in general, and the increase in retake probability when confronting the failure of scoring just below the cutoff is also more pronounced for men than for women. The gender disparity in the tendency to retake has important implications for exam performance, college quality, and labor market outcomes.

Understanding the causes and consequences of the gender disparities in educational outcomes and labor market outcomes is crucial for providing policy implications and has attracted increasing attention among economists. Previous studies have documented that gender differences in non-cognitive traits and attitudes, such as willingness to compete, pressure tolerance, risk aversion, and confidence, may explain an important part of the gender gaps in educational choices and labor market outcomes (see a review article by Delaney and Devereux 2021). However, less is known about the gender differences in reactions to failure and its mechanisms and implications, which is important because people confront numerous competitions throughout their career for college admission, jobs, and promotions, and failures and setbacks in these competitions are not uncommon for most people. Different responses to failure, such as whether to try again in subsequent competitions or give up, may lead to very different educational achievements and career paths.

A growing body of literature shows the gender differences in the willingness to participate and the performance in competitions (Niederle and Vesterlund 2007; Buser, Niederle, and Oosterbeek 2014; Flory, Leibbrandt, and List 2015; Berlin and Dargnies 2016; Buser, Peter, and Wolter 2017; Reuben, Wiswall, and Zafar 2017; Cai et al. 2019). In recent years, some studies have focused on gender differences in the dynamic evolution of willingness to compete in response to winning and losing. They have documented that when confronting failures in competitions, women are less likely to choose competition again than men in lab experiments and in high school math competitions in the Netherlands and the United States (Buser and Yuan 2019; Ellison and Swanson 2018), in the entrance exam of the elite science graduate programs in France (Landaud and Maurin 2020), and in local elections in California (Wasserman 2020). However, these studies focus on either competitions with low-stakes, or a relatively selective group of people that choose to enter the competition in the first place and may be different from the general population, which raises concerns about how to interpret these findings in different contexts, for competitions with higher stakes, and for more general population.

In Kang, Lei, Song, and Zhang (2021), we document gender differences in reactions to failure in a real-world competition with extremely high stakes: the National College Entrance Exam (NCEE), which is also commonly known as gaokao, in China. The NCEE is an annual exam that solely determines the admission of almost all teenagers into higher education institutions in China. Over 2,000 universities in China are classified into four tiers, with NCEE score cutoffs determining the eligibility of application for each tier. Around 10 million students take the NCEE to compete for admissions to the highly selective universities each year, with only around 25% of students receiving scores that make them eligible to apply for high-quality universities in the top two tiers. The NCEE is highly competitive and often described as the “toughest exam in the world,” and the sense of competition and failure is very strong in this setting.

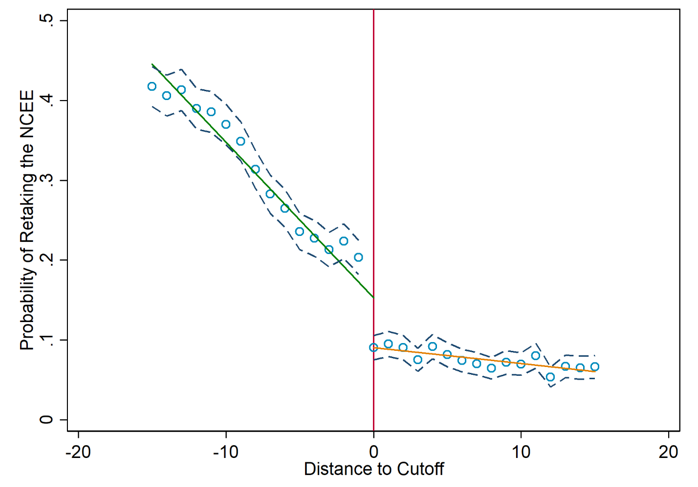

We use unique administrative data for the universe of NCEE takers in Ningxia Province (Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region) from 2002 to 2010 and exploit a regression-discontinuity design to investigate the choice of retaking the NCEE when confronting failure in this high-stakes competition and its causal effects on exam performances. Figure 1 plots the probability of retaking the NCEE in the next year against the distance to the tier-2 cutoff score. There is a notable discontinuity in retake probability around the cutoff point, and our estimates show that students who score just below the tier-2 cutoff, a signal of entering good universities and educational success, have an eight-percentage-point higher probability of retaking the NCEE in the next year, almost doubling that of those who score just above the cutoff. We then exploit the discontinuity in retake probability around the tier-2 cutoff to estimate the causal effects of retaking the NCEE on exam performance. Our results show that retaking the NCEE increases the test scores by 0.47 standard deviations, and increases the relative ranking among competitors by 11 percentage points. These improvements in exam performance are consequential; our results show that these improvements translate to a 51 to 62 percentage point higher probability of scoring above the tier-1 cutoff in the end, which amounts to a 5.2 to 9.7% higher wage offer for the first job after college (Jia and Li 2021). Our estimates of the effects of retaking the NCEE on exam performance are comparable to and even larger than the estimates for other admission-relevant exams such as SAT (Goodman, Gurantz, and Smith 2020).

Figure 1: The Probability of NCEE Retaking vs. Distance to Tier-2 University Cutoff Score

Notes: This figure plots the probability of retaking the NCEE in the next year against the distance to the tier-2 cutoff score. The sample consists of observations within the 15-point bandwidth around the cutoff. Each circle corresponds to one point in the test score. The straight lines represent the fitted linear functions to the left and to the right of the cutoff. The dashed lines represent the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval for the sample mean of the outcome variable within the corresponding bin.

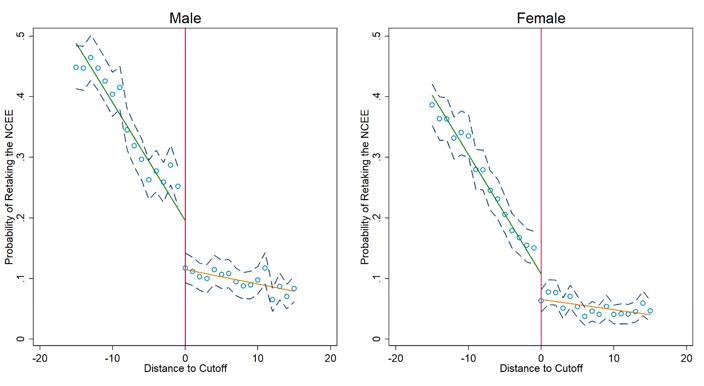

Despite the sizable returns, there are large gender differences in the propensity to participate in the competition again in the next year. We find consistent evidence that women are less likely to retake the NCEE than men with similar exam performance. In addition, the cutoff-induced retakes from the regression discontinuity design, which reflect the desire to participate in the competition again inspired by the failure of scoring below the cutoff, are also much more pronounced for men than for women. Figure 2 plots the probability of retaking the NCEE in the next year against the distance to the tier-2 cutoff separately for males and females. It is clear that males have a higher retake probability than females on both sides of the cutoff, and the discontinuity in retake probability at the cutoff is much more pronounced for males than for females. Our results show that the increase in retake probability when falling just below the tier-2 cutoff for males is twice as large as for females (11 versus 5.5 percentage points, respectively).

Figure 2: The Probability of NCEE Retaking vs. Distance to Tier-2 University Cutoff Score, by Gender

Notes: This figure plots the probability of retaking the NCEE in the next year against the distance to the tier-2 cutoff score separately for males and females. The left panel is for males, and the right panel is for females. The sample consists of observations within the 15-point bandwidth around the cutoff. Each circle corresponds to one point in the test score. The straight lines represent the fitted linear functions to the left and to the right of the cutoff. The dashed lines represent the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval for the sample mean of the outcome variable within the corresponding bin.

We detect several important mechanisms that can help explain why women are less likely to retake the NCEE than men when scoring just below the cutoff, and provide evidence to help distinguish between the possible explanations. We find that the returns to retake in terms of exam outcomes for women are similar to or sometimes even higher than those for men. In addition, we find that the gender differences are large and of similar magnitude for individuals from urban and rural households, of different ethnicities, from high-quality and low-quality high schools, from rich and poor counties, and from places with high and low levels of sex ratio. These results suggest that gender differences in benefits and costs of retake, as well as in social norms and family support, are unlikely to fully explain our results. They also show that gender differences in reactions to failure are not driven by certain groups, but are pronounced for all types of individuals. By contrast, our results may be explained by gender differences in non-cognitive traits, such as causal attribution, confidence, and risk preferences. We find that the gender differences are much smaller for repeated takers, which is consistent with this explanation.

Taken together, our findings provide evidence on gender differences in reactions to failure that are consistent with previous studies, but in a setting with higher stakes and for a much larger population. Our estimates suggest that if females are equally likely to retake as males, females would have better exam performances and be substantially more represented in the high-quality universities, which may in turn, have important implications for the gender equality in the labor market.

(Le Kang, Institute of Education Research, Nanjing University; Ziteng Lei, School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China; Yang Song, Department of Economics, Colgate University; Peng Zhang, School of Management and Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.)

References

Berlin, Noémi, and Marie-Pierre Dargnies. 2016. “Gender Differences in Reactions to Feedback and Willingness to Compete.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 130: 320–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.08.002.

Buser, Thomas, Muriel Niederle, and Hessel Oosterbeek. 2014. “Gender, Competitiveness, and Career Choices.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (3): 1409–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju009.

Buser, Thomas, Noemi Peter, and Stefan C. Wolter. 2017. “Gender, Competitiveness, and Study Choices in High School: Evidence from Switzerland.” American Economic Review 107 (5): 125–30. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171017.

Buser, Thomas, and Huaiping Yuan. 2019. “Do Women Give Up Competing More Easily? Evidence from the Lab and the Dutch Math Olympiad.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11 (3): 225–52. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170160.

Cai, Xiqian, Yi Lu, Jessica Pan, and Songfa Zhong. 2019. “Gender Gap under Pressure: Evidence from China’s National College Entrance Examination.” Review of Economics and Statistics 101 (2): 249–63. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00749.

Delaney, Judith M., and Paul J. Devereux. 2021. “Gender and Educational Achievement: Stylized Facts and Causal Evidence.” Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper No. 14074. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/14074/gender-and-educational-achievement-stylized-facts-and-causal-evidence.

Ellison, Glenn, and Ashley Swanson. 2018. “Dynamics of the Gender Gap in High Math Achievement.” NBER Working Paper No. 24910. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24910.

Flory, Jeffrey A., Andreas Leibbrandt, and John A. List. 2015. “Do Competitive Workplaces Deter Female Workers? A Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment on Job Entry Decisions.” Review of Economic Studies 82 (1): 122–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdu030.

Goodman, Joshua, Oded Gurantz, and Jonathan Smith. 2020. “Take Two! SAT Retaking and College Enrollment Gaps.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12 (2): 115–58. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170503.

Jia, Ruixue, and Hongbin Li. 2021. “Just Above the Exam Cutoff Score: Elite College Admission and Wages in China.” Journal of Public Economics 196 (April), 104371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104371.

Kang, Le, Ziteng Lei, Yang Song, and Peng Zhang. 2021. “Gender Differences in Reactions to Failure in High-Stakes Competition: Evidence from the National College Entrance Exam Retakes.” http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3861378.

Landaud, Fanny, and Éric Maurin. 2020. “Aim High and Persevere! Competitive Pressure and Access Gaps in Top Science Graduate Programs.” Paris School of Economics Working Paper 03065958. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03065958.

Niederle, Muriel, and Lise Vesterlund. 2007. “Do Women Shy Away from Competition? Do Men Compete Too Much?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (3): 1067–1101. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1067.

Reuben, Ernesto, Matthew Wiswall, and Basit Zafar. 2017. “Preferences and Biases in Educational Choices and Labour Market Expectations: Shrinking the Black Box of Gender.” Economic Journal 127 (604): 2153–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12350.

Wasserman, Melanie. 2020. “Gender Differences in Politician Persistence.” http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3370587.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email