Chinese Economic Growth Doesn’t Appear Overstated, but Its Heavy Reliance on Credit May Be a Cause for Concern

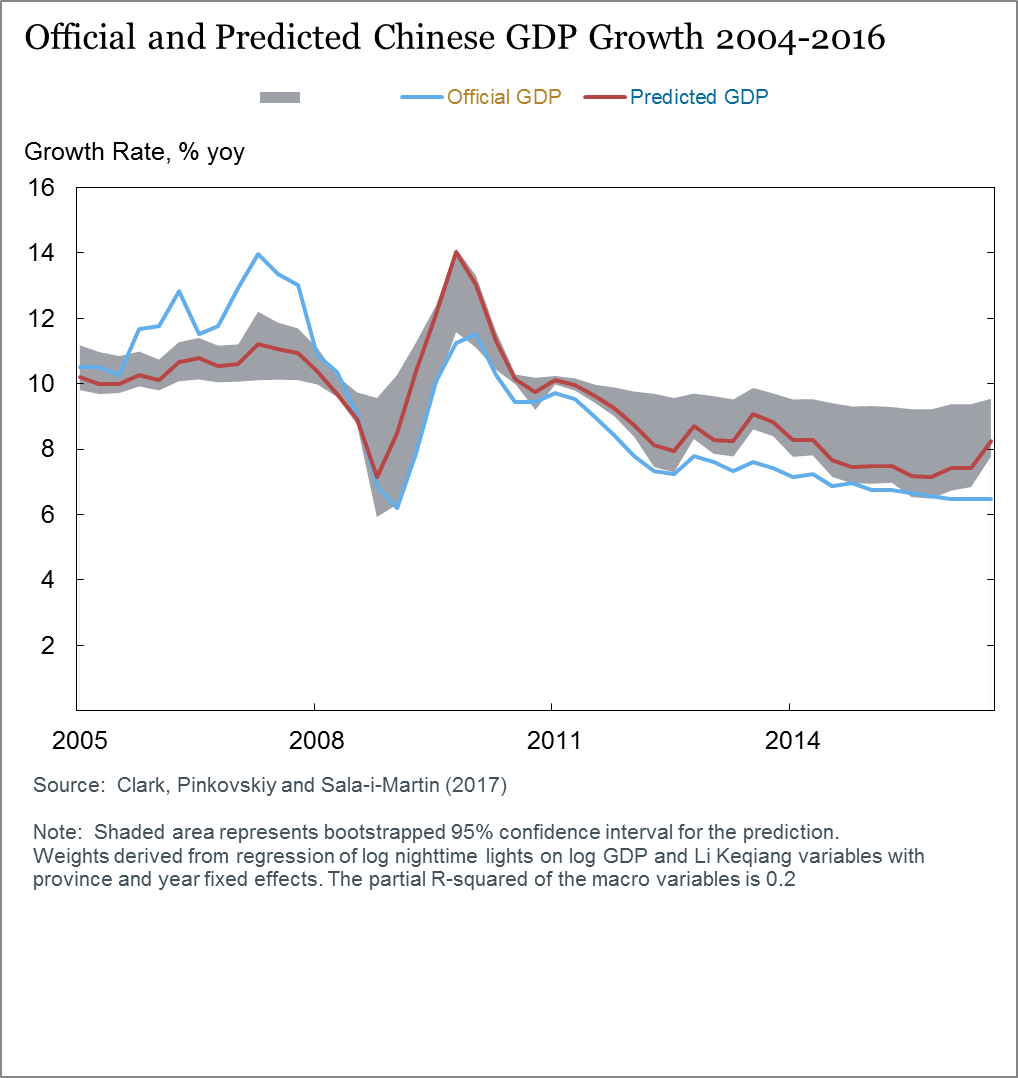

Are China’s official GDP growth number exaggerated? Hunter Clark, Jeff Dawson and Maxim Pinkovskiy from the New York Fed and Xavier Sala-i-Martin from Columbia University use satellite measurements of the intensity of China’s nighttime light emissions to proxy for GDP growth. Their estimate of Chinese GDP growth, since 2012, was never appreciably lower, and was in many years higher, than the GDP growth rate reported in the official statistics.

For analysts of the Chinese economy, doubts about the accuracy of the country’s official GDP data lead many to seek guidance from alternative indicators. These nonofficial gauges often suggest that Beijing’s growth figures are exaggerated. This conclusion, however, is not supported by our analysis, which draws upon satellite measurements of the intensity of China’s nighttime light emissions—a feasible proxy for GDP growth. More worrisome, however, is that China’s recent GDP growth has been driven by a historic credit boom that does not appear sustainable.Recent efforts by Chinese authorities to rein in credit growth are encouraging, but they may be challenging to manage and could spill over into international markets given the size of the Chinese economy.

Doubts about the Official Data

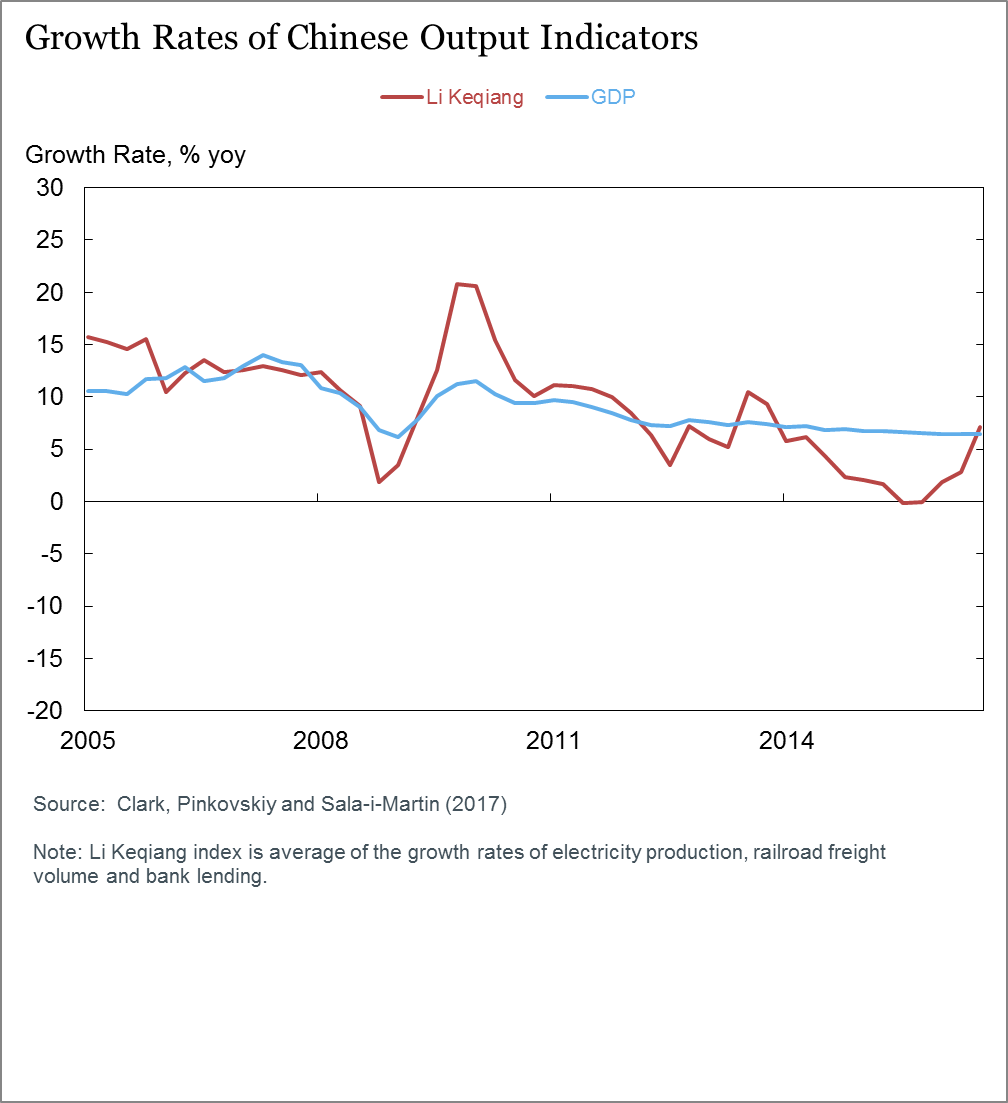

In the eyes of many observers,China’s economy seemed to be entering a tailspin in 2015. And yet, the official GDP data showed a negligible slowdown in growth. The financial press pounced on these “questionable” statistics, citing a now-famous 2007 exchange between Premier Li Keqiang, then a provincial Communist Party secretary, and U.S. Ambassador Clark Randt. Li admitted that he preferred to assess the performance of his province’s economy by averaging the growth rates of electricity production, rail freight, and bank loans.Li’s metric—since dubbed the “Li Keqiang index”—has declined for four of the past six years, recording a precipitous drop in 2015. Such signals have prompted many observers to believe the Chinese economy is weaker than official statistics portray it to be (notwithstanding the fact that the index rose over the course of 2016). Skeptical of the official numbers, many Wall Street analysts have constructed their own models of Chinese economic growth, suggesting that growth in the last quarter of 2015 was indeed much lower than the official rate of 6.8 percent. Some analysts claim that the “true” figure is less than 5 percent.

Imperfect Alternatives

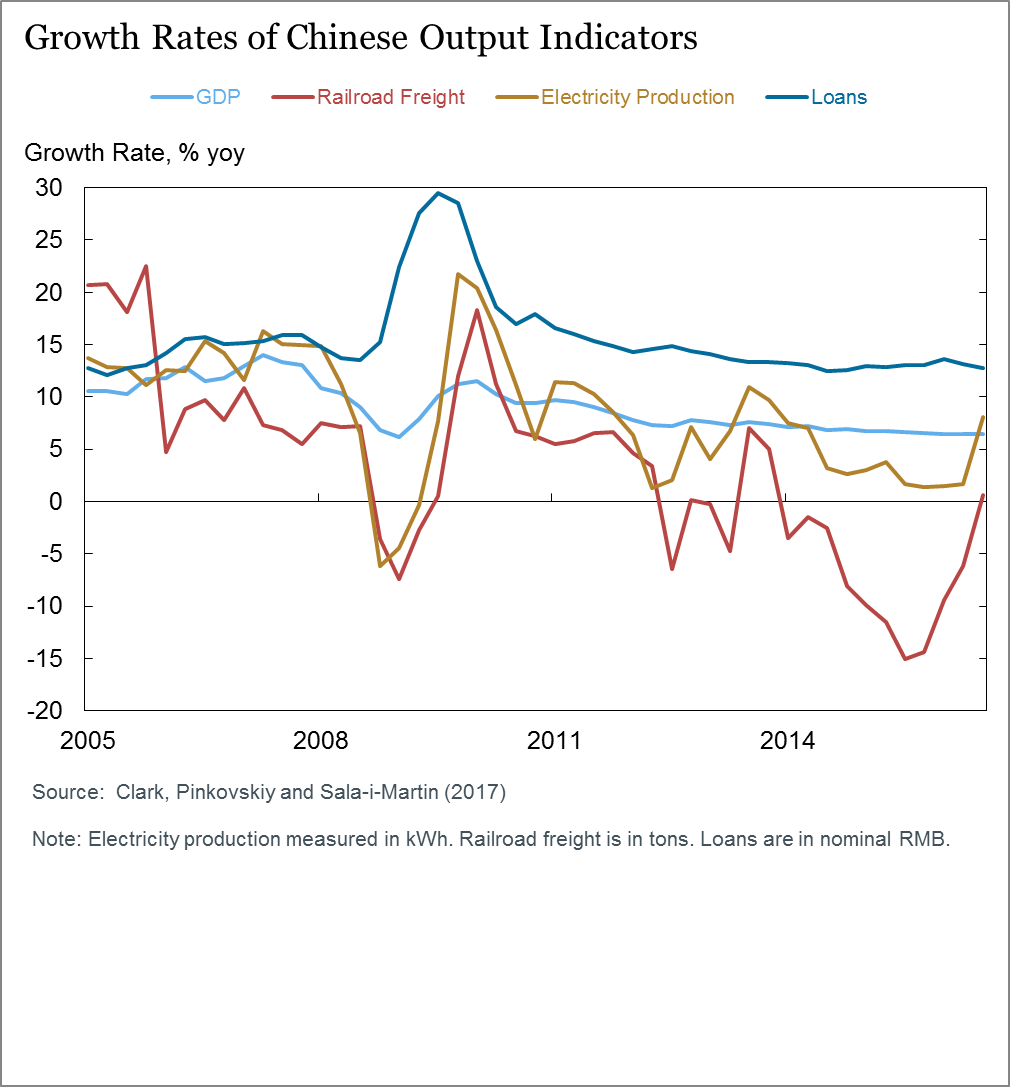

These nonofficial indices are all based on assumptions about and models of the Chinese economy that are difficult to express, let alone test. As the chart below shows, the components of the Li Keqiang index—the growth rates of electricity production, rail freight, and bank loans—have followed separate trajectories over the past twelve years. Placing greater weight on any one of these inputs would produce a much different stream of GDP growth estimates.

In light of the structural changes under way in the Chinese economy, we might devise a modified Li Keqiang index, placing more weight on the bank loans series than on the rail freight series, as opposed to weighting the three growth rate series equally. This approach would have engendered much less concern at the end of 2015.

Satellite Readings

To resolve these credibility issues, we need to develop a transparent, data-driven procedure centered on an independent gauge of Chinese economic growth. We argue that such a measure exists in the form of satellite-recorded data on the brightness of nighttime lights across Chinese provinces over time. It has been well established that growth in nighttime light intensity is a good proxy for economic growth.The heart of our analysis is a regression of growth in nighttime lights across Chinese provinces and over time on the growth rates of the various statistical series used to calculate the Li Keqiang index. Using the key assumption that measurement errors in nighttime lights are independent of the measurement errors of the other variables utilized, the regression coefficients on the statistical series are proportional to the optimal weights that should be applied to these measures in order to derive predictions for true Chinese GDP growth.

Reweighting the Li Keqiang Index

We find that the components of the Li Keqiang index should not be assigned equal weighting, as is typically supposed. In fact, our analysis indicates that bank loan growth should be given six to eight times more weight than rail freight growth, with the optimal weighting on electricity production growth somewhere in between these two. The implications of this reweighting on our optimal estimate of Chinese GDP growth are profound. We find that since 2012, our estimate of Chinese GDP growth was never appreciably lower, and in many years was higher, than the GDP growth rate reported in the official statistics. Adding other series besides those incorporated in the Li Keqiang index does not change our results. In fact, our estimate for Chinese growth shows an appreciable acceleration in 2016, even as the official growth rate remained virtually unchanged.

Some Cause for Concern

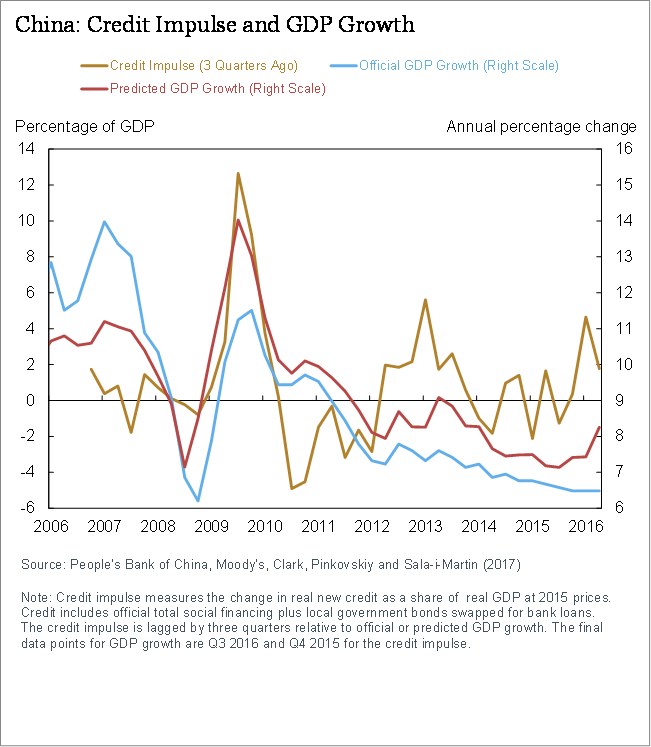

Nonfinancial debt in China has increased from roughly $3 trillion at the end of 2005 to nearly $25 trillion, while banking system assets have increased sixfold over the same period to over 300 percent of GDP. In 2016 alone, the amount of credit outstanding increased by more than $3 trillion, with the pace of growth still well above nominal GDP. As a result, the “credit-to-GDP gap”—the difference between the debt-to-GDP ratio and its long-run trend—has reached almost 30 percentage points. The international experience suggests that such a rapid buildup is often followed by stress in domestic banking systems. Roughly one-third of boom cases end up in financial crises one-third of boom cases end in financial crises and another third precede extended periods of below-trend economic growth.

Is Credit Now Offering Less of a Boost to Growth?

Improvements in credit efficiency going forward will require reforms, such as hardening budget constraints at state-owned enterprises and local governments, reducing implicit and explicit guarantees in the financial system, improving regulatory oversight and coordination, and slowing aggressive balance sheet growth at smaller financial institutions.

Substantial Buffers Remain

Despite its vulnerabilities, China’s financial system has several features that reduce the associated risks. Unlike many emerging market credit booms that have ended in busts, China’s credit growth has been funded primarily by high domestic saving, mainly in the form of bank deposits. Chinese authorities have sufficient liquidity tools, including high required reserve ratios, the ability to extend short-term liquidity via an array of facilities, and a financial sector dominated by state-owned lenders and borrowers. China also has substantial fiscal resources to address losses in its financial system and among troubled state-owned debtors. This last consideration is very important; the Chinese government’s strong balance sheet should provide the necessary capacity to absorb potential losses from a financial disruption. Still, the speed and increasing complexity of the country’s credit growth suggest that there could be significant benefits for China in comprehensively addressing its banking system and in financial reforms.

(Hunter Clark, Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group; Jeff Dawson, Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group; Maxim Pinkovskiy, Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group, Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Department of Economics at Columbia University.)

References

Hunter Clark, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, “Is Chinese Growth Overstated?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), April 19, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/04/is-chinese-growth-overstated.html.

Jeff Dawson, Alex Etra, and Aaron Rosenblum, “China’s Continuing Credit Boom," Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), February 27, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/02/chinas-continuing-credit-boom.html.

Hunter Clark, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, “China’s GDP Growth May be Understated” NBER Working Paper No. 23323, April, 2017. Hunter Clark, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, “China’s GDP Growth May be Understated” NBER Working Paper No. 23323, April, 2017. http://www.nber.org/papers/w23323The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email