China’s Successful Securities Regulation to Protect Investors

In emerging markets, controlling shareholders may extract private benefits at the expense of minority investors. To safeguard cash-flow rights, regulators have turned to dividend requirements, yet their rigidity risks stifling investments and growth. In China, the regulator successfully adopted an intermediate “comply-or-explain” approach to strengthen investor protection without forcing firms to forgo investments and growth.

Regulations for investor protection

Investor protection is a central concern for policymakers in emerging markets. Weak institutions, coupled with concentrated ownership, make it easier for controlling shareholders to divert resources at the expense of minority investors. Such behavior undermines both trust in capital markets and long-term growth by discouraging foreign investments (La Porta et al 2002, Piotroski and Wong 2012).

How, then, can regulation effectively curb expropriation? In many jurisdictions, supervisory bandwidth is constrained, so relying solely on regulators as a line of defense is often unrealistic. At the same time, one-size-fits-all mandates—such as blanket dividend requirements—protect investors’ cash flow rights but risk distorting corporate decisions, especially for growth firms with a high marginal value of internal cash (Albuquerque and Wang 2008). Such rules can ultimately sacrifice investment and innovation, undermining the very economic dynamism that securities markets are intended to foster.

To illustrate how regulations can better protect investors in emerging economies without stifling growth, our recent research (Bourveau et al. 2025) investigates the effectiveness of a flexible form of “comply-or-explain” regulation implemented by China’s Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) that aimed to increase dividend payouts and enhance investor protection (SSE 2012).

China’s “pay-or-explain” regulation

In 2012, the SSE introduced a “pay-or-explain” regulation, giving firms with positive undistributed and current-year profits two choices:

1. Pay at least 30% of annual profits as cash dividends, or

2. Explain publicly, through an online investor conference call, why they were not meeting the requirement.

This design sought to balance two objectives. By requiring a minimum payout, the rule curtailed controlling shareholders’ ability to siphon off cash. By offering the option to explain publicly, it gave firms with growth opportunities the flexibility to retain cash, subject to heightened scrutiny by regulators and investors.

Economic consequences of the regulation

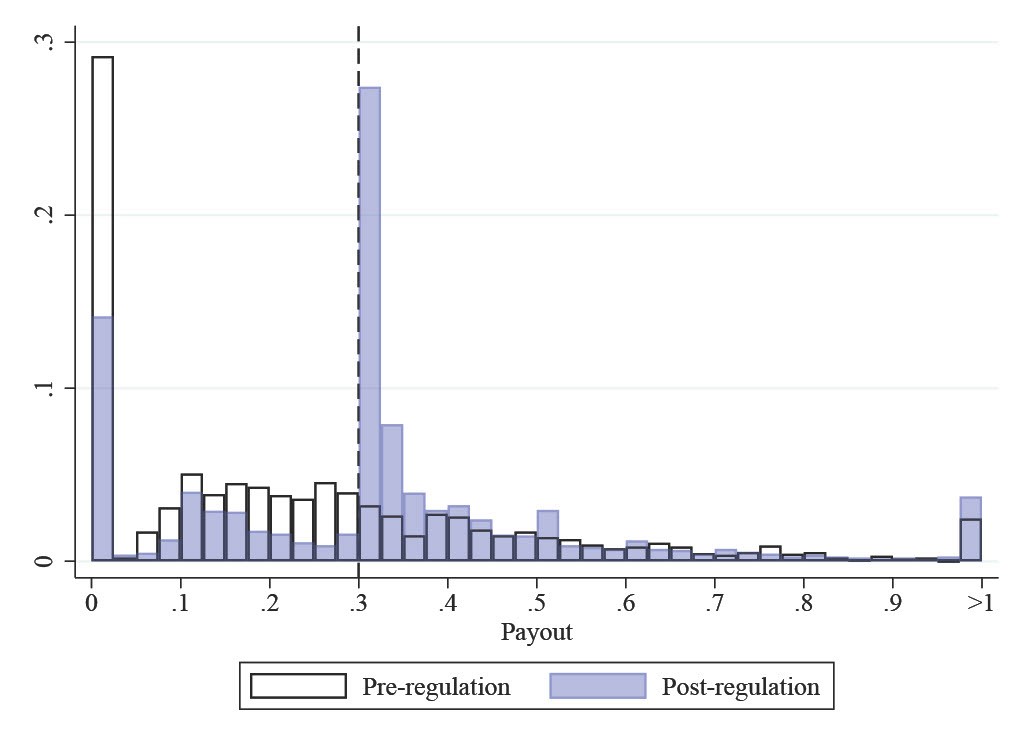

Compliance was nearly universal. Roughly 98% of eligible SSE firms either paid or explained after the regulation’s implementation. Dividend payout shifted sharply toward 30%: the share of applicable firms meeting or exceeding the 30% threshold jumped from 32% to 75% in the first year after the regulation’s implementation (Figure 1). The use of dividend conference calls to explain nonpayment more than doubled, from 9% to 28%.

Figure 1: Pre- and post-regulation dividend payouts for SSE firms

Tunneling decreased substantially. Tunneling is an important form of shareholder expropriation in China (Johnson et al. 2000, Jiang et al. 2010). We proxy firms’ tunneling with financing related-party transactions (RPTs) scaled by total assets. As illustrated by Fisman and Wang (2010), a related party may take a guarantee to secure a loan and use the funds to finance projects that generate private benefits for the controlling shareholder, despite a high risk of default. In the event of default, minority shareholders’ wealth is expropriated. Using Shenzhen-listed firms as a control group, our difference-in-differences estimates suggest that the decline in treated firms’ financing RPTs is about 1.14 percentage points of total assets, relative to the control firms. The reduction is economically significant: the decrease represents about 38% of the average financing RPTs of the treated firms prior to the regulation. Importantly, although firms differ in their perceptions of the trade-offs between “pay” vs. “explain,” the net effect on tunneling following the regulation is similar, regardless of firms’ compliance pathways.

Deeper dive into the efficacy

Less “expropriable” cash for payers. In theory, cash dividends constrain tunneling by directly reducing the volume of cash available for the activity (Faccio et al. 2001). In the data, firms that complied by meeting the 30% requirement held less excess cash—that is, the difference between actual and optimal cash holdings. We measure optimal cash levels using the predicted value from a regression of the natural logarithm of the cash ratio on a set of firm characteristics (e.g., Faleye 2004, Gao et al. 2009). In contrast, we find no statistically significant changes in excess cash among firms that opted to explain nonpayment. The finding is consistent with the regulators’ intention of allowing explaining firms to retain cash for internal usage.

Heightened monitoring for explainers. The comply-or-explain regulation concentrates regulatory resources on firms that opt to explain nonpayment, rather than spreading these resources across all firms. For example, the SSE established dedicated task forces to monitor the communications of explainers. Our evidence indicates an improvement in regulatory monitoring in the form of more supervisory letters on governance-related issues—such as expropriation of corporate assets, misuse of funds, inappropriate loan guarantees, and false or misleading disclosures—for explainers but not payers. Complementing regulatory monitoring, minority investors engaged more actively during explainers’ shareholder meetings to make their voice heard.

Explanations are not cheap talk. Corporate communications proved informative. During the online dividend calls, investors pressed managers on payout policy in roughly three-quarters of cases, and managers’ stated reasons for retaining cash aligned with subsequent actions. For example, firms citing fixed-asset investments exhibit higher capital expenditures. The evidence suggests that credibility matters: when explanations are falsifiable and archived in public, they serve as commitments that regulators and investors can verify ex post.

Concluding remarks

The lessons above have implications beyond the Chinese setting. For regulators confronting similar securities market problems, smarter rules can trump more rules. The success of the “comply-or-explain” model likely rests on a few key factors. First, regulators should direct their efforts and resources toward areas where risks are the highest. In our setting, the SSE deployed dedicated task forces to monitor explainers, and the credibility of the targeted approach was reinforced by 98% compliance among eligible firms. Second, the innovative form of disclosure (i.e., online conference calls) significantly mobilized minority shareholders and created verifiable records such that investors’ monitoring could complement regulators’ oversight. This approach aligns with the CSRC’s broader goal of gradually introducing more market forces into the Chinese securities market (Lennox and Wu 2022).

References

Albuquerque, Rui, and Neng Wang. 2008. “Agency Conflicts, Investment, and Asset Pricing.” Journal of Finance 63 (1): 1–40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25094433.

Bourveau, Thomas, Xingchao Gao, Rongchen Li, and Frank S. Zhou. 2025. “Comply-or-Explain Regulation and Investor Protection.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 79 (2–3): 101765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2025.101765.

Bushee, Brian J., and Christian Leuz. 2005. “Economic Consequences of SEC Disclosure Regulation: Evidence from the OTC Bulletin Board.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 39 (2): 233–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.04.002.

Faccio, Mara, Larry H. P. Lang, and Leslie Young. 2001. “Dividends and Expropriation.” American Economic Review 91 (1): 54–78. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.1.54.

Faleye, Olubunmi. 2004. “Cash and Corporate Control.” Journal of Finance 59 (5): 2041–60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3694816.

Fisman, Raymond, and Yongxiang Wang. 2010. “Trading Favors within Chinese Business Groups.” American Economic Review 100 (2): 429–33. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.429.

Gao, Feng, Joanna Shuang Wu, and Jerold Zimmerman. 2009. “Unintended Consequences of Granting Small Firms Exemptions from Securities Regulation: Evidence from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.” Journal of Accounting Research 47 (2): 459–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2009.00319.x.

Jiang, Guohua, Charles M.C. Lee, and Heng Yue. 2010. “Tunneling through Intercorporate Loans: The China Experience.” Journal of Financial Economics 98 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.05.002.

Johnson, Simon, Peter Boone, Alasdair Breach, and Eric Friedman. 2000. “Corporate Governance in the Asian Financial Crisis.” Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1–2), 141–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00069-6.

La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny. 2002. “Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation.” Journal of Finance 57 (3): 1147–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00457.

Lennox, Clive, and Joanna Shuang Wu. 2022. “A Review of China-Related Accounting Research in the Past 25 Years.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 74 (2–3): 101539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2022.101539.

Piotroski, Joseph D., and T. J. Wong. 2012. “Institutions and Information Environment of Chinese Listed Firms.” In Capitalizing China, edited by Joseph P. H. Fan and Randall Morck. University of Chicago Press.

Shanghai Stock Exchange. 2012. “Shanghai Stock Exchange Press Conference on the Guidelines of Cash Dividends for Listed Firms.” https://www.sse.com.cn/aboutus/mediacenter/hotandd/c/c_

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email