Quarters of Birth Matter for Girls: How Agricultural Seasonality Shapes Gender Inequality in China

We find that people born in the fourth quarter tend to have better lifecycle outcomes than others in China. More importantly, this birth quarter effect is significantly larger for females than for males. Such a gendered pattern is likely driven by seasonal variations in household resources induced by agricultural seasonality, which may exert gender-differentiated effects on intrahousehold neonatal investment due to son preference. These findings have meaningful implications for the role of economic development in reducing gender inequality through the (gender-neutral) increase in household resources.

Background

Gender inequality remains one of the most persistent challenges in developing economies. Despite substantial progress in recent decades, women in developing countries continue to lag behind men in education, health, and labor market outcomes (Duflo 2012). A critical question for policymakers is understanding how economic development can reduce these disparities without directly targeting cultural norms or implementing costly gender-specific interventions.

Prior studies have shown that when families face severe resource constraints, parents are more likely to allocate fewer resources to daughters than sons, particularly in societies with strong son preferences (Rose 1999, Duflo 2012). Moreover, the impact of an increase in household resources may depend on the gender of the resource recipient in a household (Duflo 2000, 2003). Nevertheless, as pointed out by Duflo (2012) in her literature review, it is still empirically unclear whether an unconditional (gender-neutral) increase in household resources would reduce gender inequality in intrahousehold investment, especially under normal circumstances (as opposed to extreme situations such as famines). The reason might be that, as Deaton (1997) suggests, it is difficult to find general variations in household resources under normal circumstances that would generate detectable gender differences in intrahousehold investment.

However, identifying the causal effects of gender-neutral variations in resource constraints on gender inequality under normal circumstances is empirically challenging, as researchers struggle to find exogenous variations in household resources that would generate detectable gender differences in investment decisions.

In our study (Qin et al. 2025), we address this gap by exploiting a previously overlooked source of variation in household resources: the seasonality of agricultural production in traditional agricultural societies (Fink et al. 2020). Based on Chinese population censuses covering cohorts born between 1940 and 1995, we document a striking pattern in how birth quarters affect lifecycle outcomes differently for men and women—and show how economic development can reduce these gender gaps by relaxing household resource constraints.

Key facts on birth quarter effects by gender

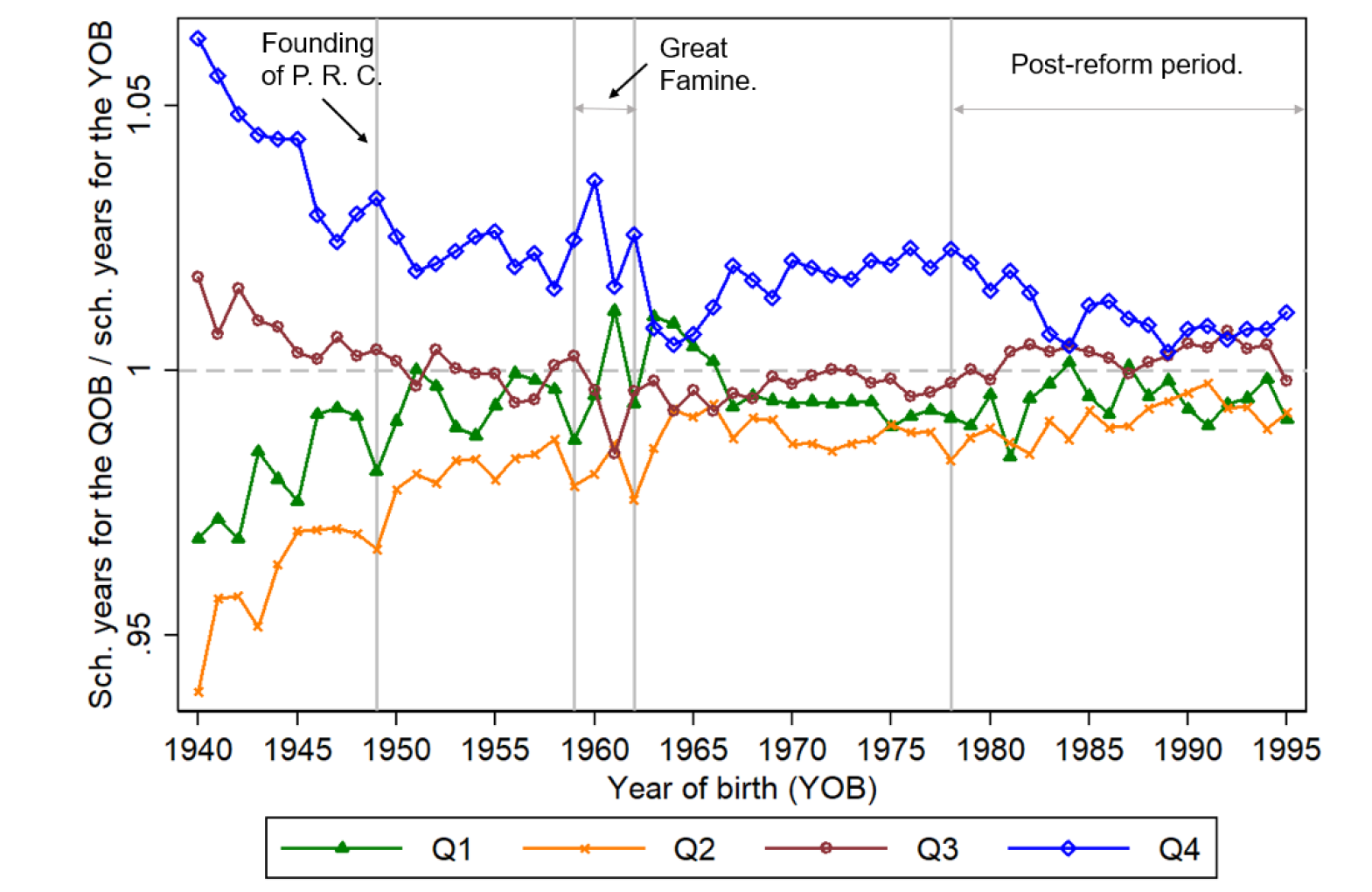

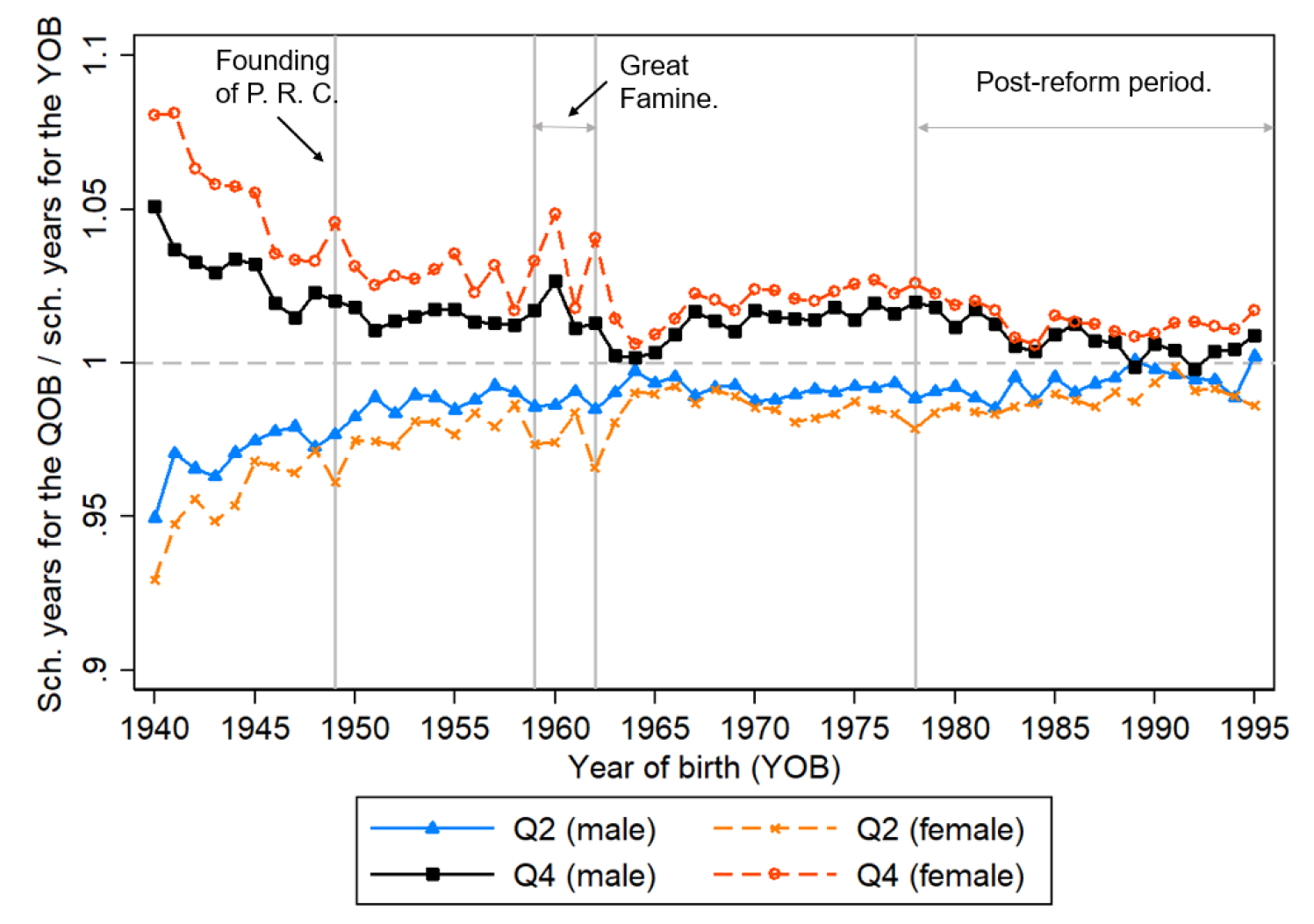

We begin with three remarkable empirical findings as shown in Figure 1: (i) People born in the fourth quarter (October–December, Q4) consistently achieve higher educational attainment than those born in other quarters in China; (ii) Such a birth quarter effect (BQE) is significantly larger for females than males; and (iii) The BQE and its gender gap vary over time in systemic ways: it spiked during China's Great Famine (1959–1962), when resources were scarce, and declined after market-oriented economic reforms in 1979.

In a regression framework, we show that compared with individuals born in the second quarter (Q2), average schooling years increase by 0.26 for females and 0.19 for males born in Q4 among the 1940–1990 birth cohorts. This gender gap in BQEs corresponds to a 5% reduction in the overall education gender gap in China. Similar patterns are observed for labor market outcomes. To identify the gender difference in BQEs, we do not require the absence of selection of birth quarters on unobservables, as long as such selection does not systematically vary between genders. This assumption is weaker than that for the identification of BQEs. Using census data, we provide two pieces of evidence to support our identification assumption. First, sex ratios are balanced between birth quarters. Second, the correlations between birth quarters and maternal characteristics are similar between boys and girls.

The agricultural seasonality mechanism

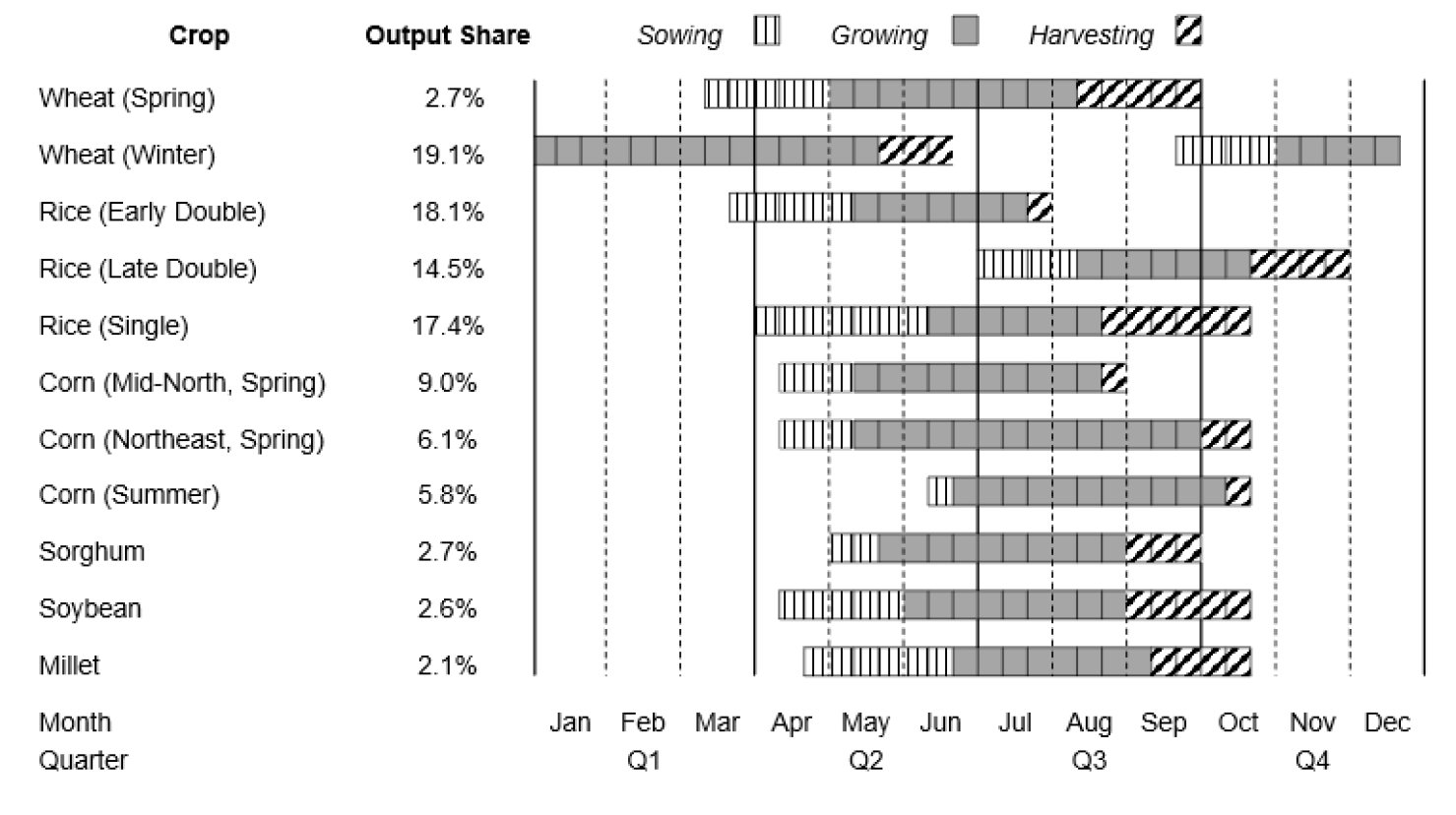

What drives these gendered birth quarter effects? We propose and test a novel mechanism centered on agricultural seasonality and its interaction with son preference. In traditional agricultural societies, household resources—both food availability and parental time for childcare—vary dramatically across seasons due to the timing of planting and harvesting cycles (Figure 2). Moreover, the pattern of agricultural seasonality exhibits substantial spatial variations across provinces in China, which we exploit to enrich our mechanism analysis as discussed below.

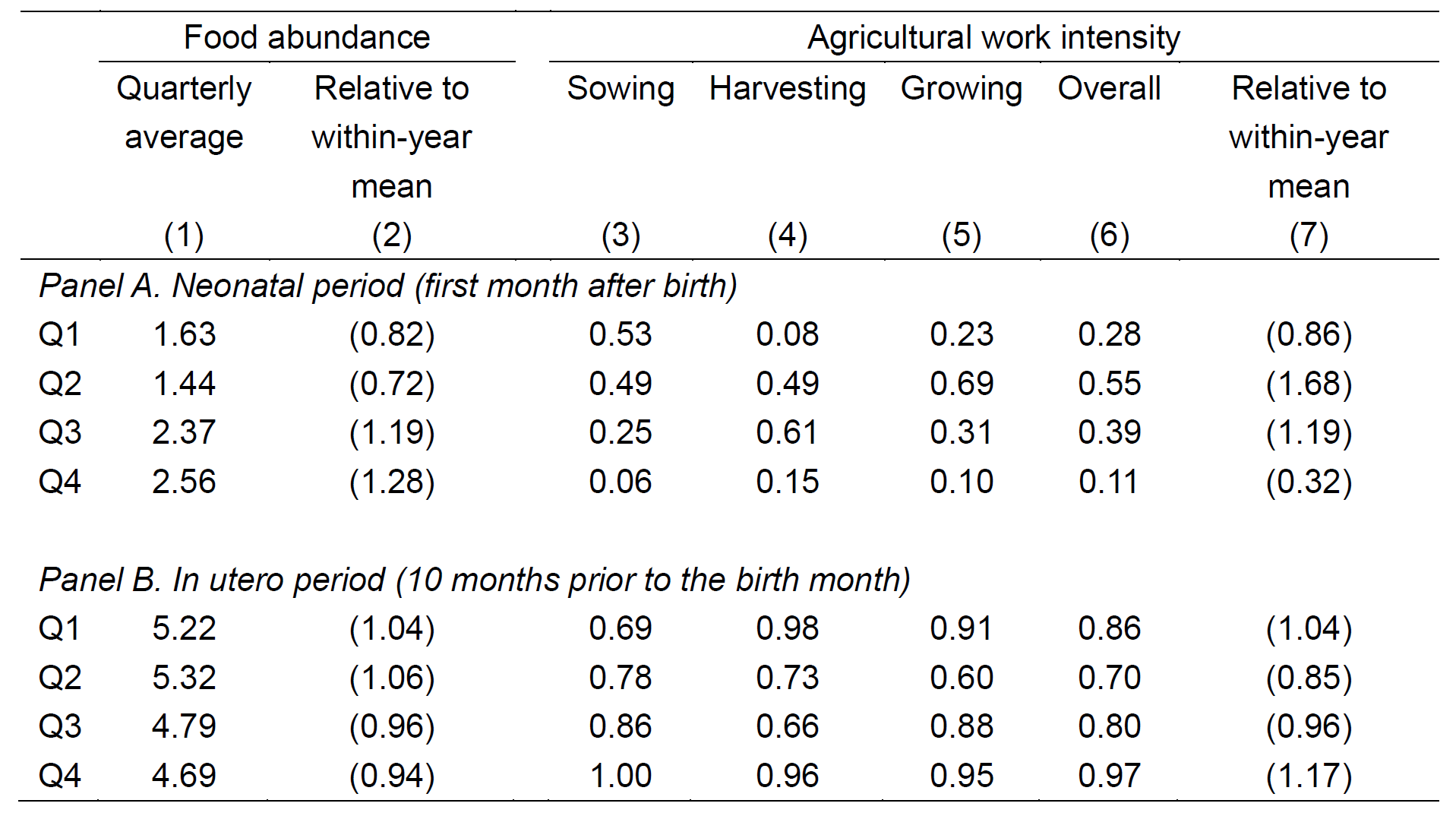

Our detailed analysis of China’s agricultural calendar reveals that household resources are most abundant for children whose critical neonatal period (the first month after birth) coincides with the fourth quarter (Q4), as shown in Table 1. These children benefit from parents having just completed the harvest, leading to peak food availability and minimal agricultural work demands (abundant parental time for childcare).

Contrarily, for other quarters when resources are scarce, e.g., for children born in lean seasons, parents with son preference allocate available resources disproportionately to boys. The result is that girls experience larger gaps in neonatal investment between lean and abundant seasons, which results in the observed gender difference in BQEs due to the persistent effect of neonatal conditions.

By exploiting the variation in crop structures and agricultural seasonal cycles across provinces in China, we find that people born in quarters with abundant resources for child neonatal investment have significantly better lifecycle outcomes, and this effect is significantly larger among females than males. Furthermore, we show that the BQEs and their gender difference are significantly larger in provinces with higher levels of seasonality in resources, and in provinces with one harvest per year compared to those with two or three harvests per year.

Evidence from weather shocks and quasi-experimental economic reform in 1979

To establish causal evidence for the agricultural seasonality mechanism, we exploit weather shocks to agricultural productivity as natural experiments, constructing measures of thermal agricultural productivity based on county-level weather records. We find that positive weather shocks in the previous year reduce BQEs, particularly for females in rural areas.

Furthermore, we leverage the 1979 rural economic reform in China as a quasi-experimental test of how economic development affects these patterns. This reform dramatically increased agricultural productivity and helped rural households smooth consumption across seasons through market mechanisms and institutional changes like the Household Responsibility System. Our analysis shows that the reform significantly reduced the effect of agricultural weather shocks on gender gaps in BQEs, providing direct evidence that economic development can promote gender equality by relaxing household resource constraints.

Evidence on infant breastfeeding

To provide direct evidence for our proposed channel of neonatal investment, we examine BQEs on infant breastfeeding—a proxy for intrahousehold neonatal investment—using data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. We find that female infants born in Q4 are significantly more likely to be breastfed than those born in other quarters, while no similar pattern is found for males. Crucially, this effect is concentrated among rural households with low socioeconomic status. This provides support for the role of household resource constraints in shaping BQEs in intrahousehold investment by gender.

Policy implications

Our findings have important implications for understanding how economic development promotes gender equality (Duflo 2012, Jayachandran 2015). Traditional policy approaches have focused on changing gender bias in culture and implementing targeted interventions for women. Our study suggests a gender-neutral pathway: economic development can reduce gender inequality even without directly targeting cultural norms, simply by relaxing the resource constraints that force families to make gender-biased allocation decisions.

The mechanisms we identify are relevant in many developing economies where agricultural seasonality remains important and son preference persists. Our results suggest that policies aimed at smoothing seasonal consumption—such as improved crop storage facilities, better access to credit markets, or agricultural productivity improvements—could have important gender equality benefits.

In addition, our study highlights the critical importance of early-life conditions for long-term gender inequality. The fact that resource constraints during the first months of life have persistent effects on educational attainment and other lifecycle outcomes underscores the high returns to ensuring adequate early-life investment for all children, regardless of gender.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: Relative Average Schooling Years by Quarter and Year of Birth

(a) Whole Sample

(b) Subsamples by Gender

Notes: Data are from Chinese population censuses (1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020). The sample includes individuals born between 1940 and 1995 and aged 25–60 in the census year. Figure (a) presents the ratio of average schooling years for each quarter of birth (QOB) over average schooling years for the corresponding year of birth (YOB). Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 indicate people born in the first, second, third, and fourth quarters, respectively. Figure (b) presents the ratio of gender-specific average schooling years for people born in Q2 and Q4 over average schooling years for the corresponding YOB in the same gender subsample.

Figure 2: Seasonal Agricultural Production in China

Notes: Data sources: China Agricultural Yearbook (1980); US Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service.

Table 1: Food Abundance and Agricultural Work Intensity by Quarter of Birth

Notes: The calculation is based on the crop calendar presented in Figure 2. See Qin et al. (2025) for details of the calculation.

References

Deaton, Angus. 1997. The Analysis of Household Surveys: A Microeconometric Approach to Development Policy. World Bank Publications.

Duflo, Esther. 2000. “Child Health and Household Resources in South Africa: Evidence from the Old Age Pension Program.” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 90 (2): 393–98. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.2.393.

Duflo, Esther. 2003. “Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old-Age Pensions and Intrahousehold Allocation in South Africa.” World Bank Economic Review 17 (1): 1–25. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/17173.

Duflo, Ester. 2012. “Women Empowerment and Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 50 (4): 1051–79. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051.

Fink, Günther, B. Kelsey Jack, and Felix Masiye. 2020. “Seasonal Liquidity, Rural Labor Markets, and Agricultural Production.” American Economic Review 110 (11): 3351–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180607.

Jayachandran, Seema. 2015. “The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Economics 7 (1): 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404.

Qin, Xuezheng, Junjian Yi, and Haochen Zhang. 2025. “Quarter of Birth, Gender Inequality, and Economic Development.” Journal of Labor Economics, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1086/737993.

Rose, Elaina. 1999. “Consumption Smoothing and Excess Female Mortality in Rural India.” Review of Economics and Statistics 81 (1): 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465399767923809.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email