Sowing Seeds of Mobility: The Uneven Impact of Land Reform

Structural transformation—the shift of labor from farming to other industries—is one of the most salient features of economic development. Yet in many developing countries, this transition is held back by potential institutional and mobility barriers.

Land market frictions due to incomplete property rights are common in rural areas of developing countries, where farmers often have usage rights but not rental or ownership rights, resulting in inefficient or absent rental markets (Chen, 2017; World-Bank, 2024). Consequently, transitioning from agriculture to non-farm work may entail forgoing land income, in addition to the forgone labor income. Given land’s central role in agricultural production, such land market frictions significantly constrain labor mobility (Ngai et al., 2019). An extreme example is the so-called “use-it-or-lose-it” practice, where failure to use land can lead to its reallocation. Households often respond by keeping some members on the farm to safeguard the land (de Janvry et al., 2015). In many cases, wives assume this role, which may explain the higher share of women engaged in agricultural work in lower-income countries (Lee, 2024).

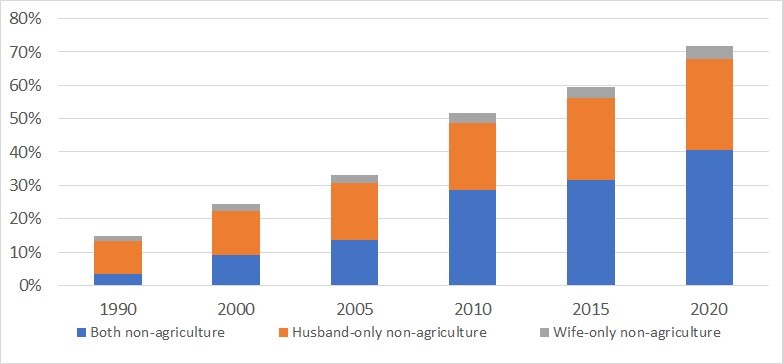

In China, this implicit barrier to mobility is made explicit through the Hukou system, which provides a unique institutional context for directly measuring the impact of such mobility constraints. The system classifies citizens as either having non-agricultural or agriculture Hukou. Those with agricultural Hukou are entitled to farm government-allocated land rent-free, but risk losing this land if they do not cultivate it (Feng et al., 2014). In our recent paper (Chen et al., 2025), we document that among rural married households, women are less likely to work in the non-agricultural sector relative to men (See Figure 1). Only after 2005 has there been an increasing trend of both partners working in non-agriculture. This shift coincides with major two land reforms implemented between 2003 and 2019.

Figure 1. Employment Pattern of Rural Married Households

Notes: Census and one percent population survey. Pairs of rural husbands and wives aged 18–55 by sectoral employment. “Both non-agriculture” denotes that both the husband and wife are employed in non-agricultural sectors. “Husband-only non-agriculture” denotes that husbands work in non-agriculture and wives do not. “Wife-only non-agriculture” denotes that wives work in non-agriculture while husbands do not.

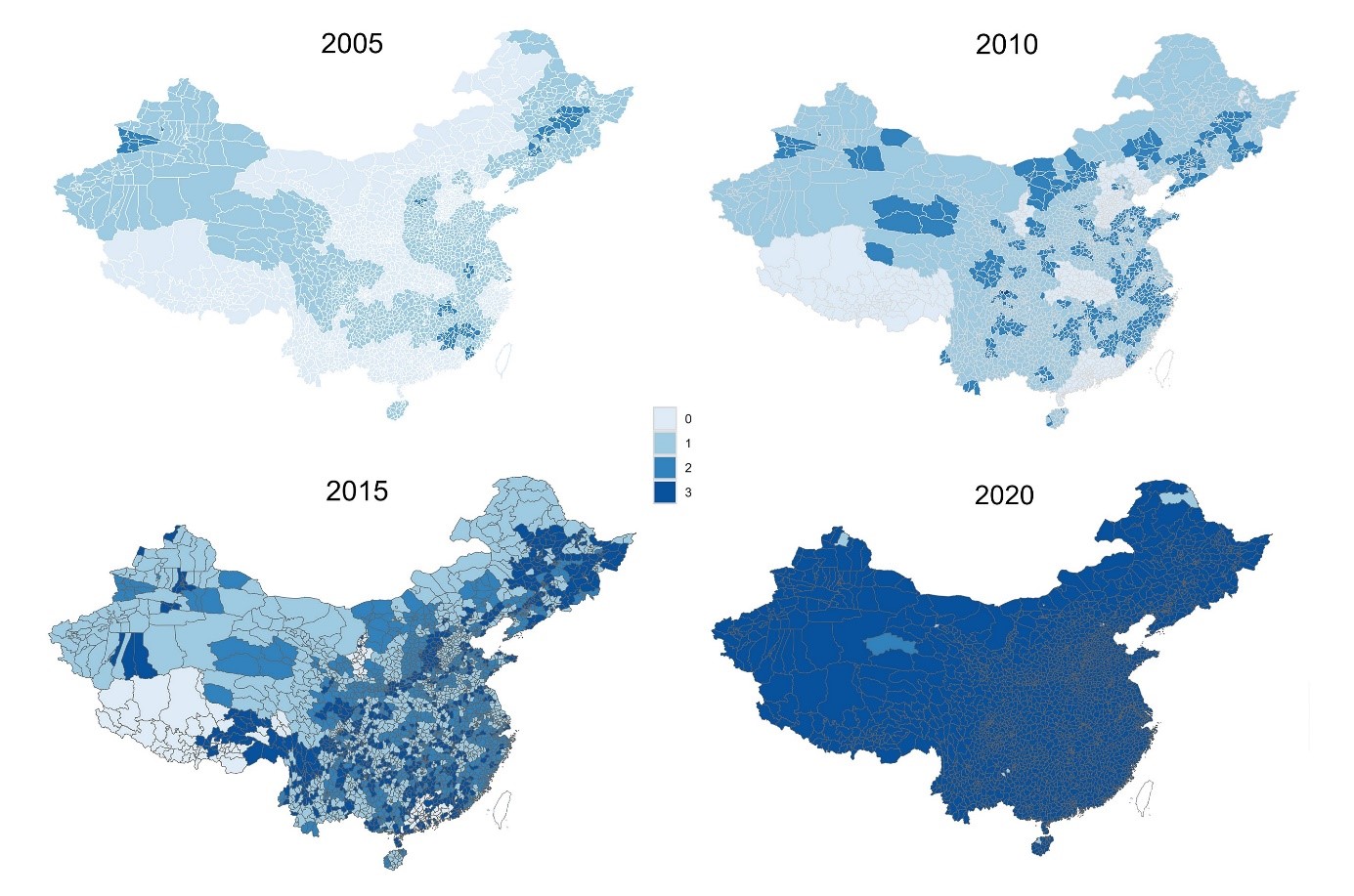

The land contracting reform (initiated in 2003) and the land titling reform (launched in 2009) both aim to safeguard agricultural households’ rights to lease and rent farmland (Chari et al., 2021, Liu et al., 2023). These reforms provided researchers with a rare opportunity to study the effects of lowering mobility barriers. To capture this, we analyze more than 4,000 government documents to construct a comprehensive and granular county-level reform index that traces the geographical and temporal diffusion of both reforms (see Figure 2). This index provides a direct measure of how barriers have evolved over time.

Figure 2. Spatial Diffusion of the Land Reform, 2003–2019

Notes: This figure matched the county-level land reform index with the 2010 Chinese prefecture-level GIS map. Darker colors represent a higher Land Reform Index. The reform index takes four potential values: 0 (No reform), 1 (Provincial regulations on land contracting reform issued), 2 (Prefecture/county regulations on land contracting reform also issued, in addition to provincial regulations), and 3 (Land titling reform completed, regardless of contracting reform). The sample did not include Taiwan.

Our land reform index advances existing measures in two key respects. First, it leverages granular county-level variation from the staggered rollout of contracting reforms, rather than relying on provincial-level data, which may fail to capture important differences across the 1,996 counties in 31 provinces. Second, it incorporates both contracting and titling reforms, providing a more comprehensive measurement of land property rights reform that spans from 2003 to 2019. The hierarchical diffusion of policies from provinces to prefecture and county levels suggests that the roll-out was likely independent of regional socioeconomic conditions, which we verify through balance tests.

Leveraging this new index and controlling for a rich set of regional economic and policy variables, along with individual factors, we show that land reform has significantly increased rental activities, signaling improved rental rights security. More importantly, we examine the impact of reform on the labor market outcomes for both agricultural Hukou and non-agricultural Hukou holders. For agricultural Hukou holders, the reforms induce rural women to leave agriculture at higher rates than rural men. Our granular county-level index is essential for identifying the impact of contracting reform on employment allocation—an effect that Chari et al. (2021) did not find when using a provincial-level index. For non-agricultural Hukou holders, the reforms lower women’s employment and wages relative to men. This is especially true for women with lower education, suggesting the presence of a substitution effect due the relative increase of female migrants.

We explain the empirical findings using a model with two sectors and two regions. In this model, rural couples decide whether one or both members should move to non-farm employment, weighing the potential loss of land income (calibrated using our empirically constructed land reform index). Given that land policy is gender neutral, why are we able to generate gender differential effects? These arise from two sets of parameters implied by the calibration. First, the non-agricultural sector employs female labor less intensively than both the agricultural and non-market (home production) sectors. Second, when women with agricultural Hukou leave the agricultural sector for non-agricultural work, the productivity of non-market sector declines. As a result, when land insecurity requires a family member to stay behind to protect land rights, it is more often the woman who remains. Consequently, reforms that strengthen land tenure security disproportionately benefit women’s non-agricultural employment.

Finally, the predicted labor reallocation boosts the relative agricultural productivity through a work intensity channel and a selection channel. First, as some individuals leave farming, the remaining workers have more land per person, which increases marginal returns from farm work and incentivizes them to work longer hours. Second, the average ability of agricultural workers increases relative to that of non-agricultural workers, since the marginal workers who move to non-agriculture tend to have lower non-agricultural ability.

This work contributes to a growing literature on mobility barriers, structural transformation, gender, and labor dynamics in developing countries. By treating land policy as both a barrier and a lever for reform, it opens new pathways for rethinking inclusive growth. As policymakers continue to tackle inequality and rural-urban divides, China’s experience offers a compelling case to consider the uneven impacts of land reforms.

References

Chari, Amalavoyal, Elaine M. Liu, Shing-Yi Wang, and Yongxiang Wang (2021). “Property Rights, Land Misallocation, and Agricultural Efficiency in China.” The Review of Economic Studies 88, no. 4: 1831–1862.

Chen, Ting, Jiajia Gu, L. Rachel Ngai, Jin Wang (2025), “Sowing seeds of mobility: the uneven impact of land reform,” CEPR working paper 20360.

Chen, Chaoran, “Untitled Land, Occupational Choice, and Agricultural Productivity (2017),” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 9(4), 9–121.

de Janvry, Alain, Kyle Emerick, Marco Gonzalez-Navarro, and Elisabeth Sadoulet (2015), “Delinking Land Rights from Land Use: Certification and Migration in Mexico,”American Economic Review,105(10), 3125–49.

Feng, Lei, Helen XH Bao, and Yan Jiang, “Land reallocation reform in rural China: A behavioral economics perspective,” Land Use Policy, 2014, 41, 246–259.

Lee, Munseob (2024), “Allocation of Female Talent and Cross-CountrTty Productivity Differences,” The Economic Journal,134(664), 3333–3359.

Liu, Shouying, Sen Ma, Lijuan Yin, and Jiong Zhu (2023). “Land Titling, Human Capital Misallocation, and Agricultural Productivity in China.” Journal of Development Economics 165: 103165.

Ngai, L. Rachel and Christopher A. Pissarides, and Jin Wang (2019), “China’s mobility barriers and employment allocations,” Journal of the European Economic Association,17(5), 1617–1653.

World-Bank, Land Policies for Resilient and Equitable Growth in Africa, Washington D.C., U.S.: World Bank Group, 2024.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email