Building Tall, Falling Short: An Empirical Assessment of Chinese Skyscrapers

Amid debates around state-led urbanization in developing countries, we analyze the causes and consequences of China’s skyscraper boom. We find that local governments often subsidize these projects through discounted land prices, motivated by political incentives. However, we find that such subsidies offer minimal long-term benefits, largely due to a mismatch with local conditions.

China’s rapid urbanization in recent decades, highlighted by a skyscraper construction boom, is remarkable. Since 2000, China has built 1,575 skyscrapers, accounting for 60% of the world’s new tall buildings. A key driver is the strong incentives for local officials to promote major projects, under the belief that modern infrastructure will attract investment and enhance their political careers (Xu 2011, Chen and Kung 2016, Wang et al. 2020). However, this assumption hinges on whether state-led projects can generate sufficient economic spillover to justify their costs—an untested premise that is of significant policy importance.

In our recent study (Chen et al. 2025), we assess the determinants and economic impacts of China’s skyscraper construction from 2006 to 2014. For this purpose, we compiled a comprehensive, geocoded dataset of all skyscrapers over 100 meters in height constructed in China during that period, along with land transaction records, firm registrations, business amenities, and infrastructure.

- What drives the skyscraper boom in China?

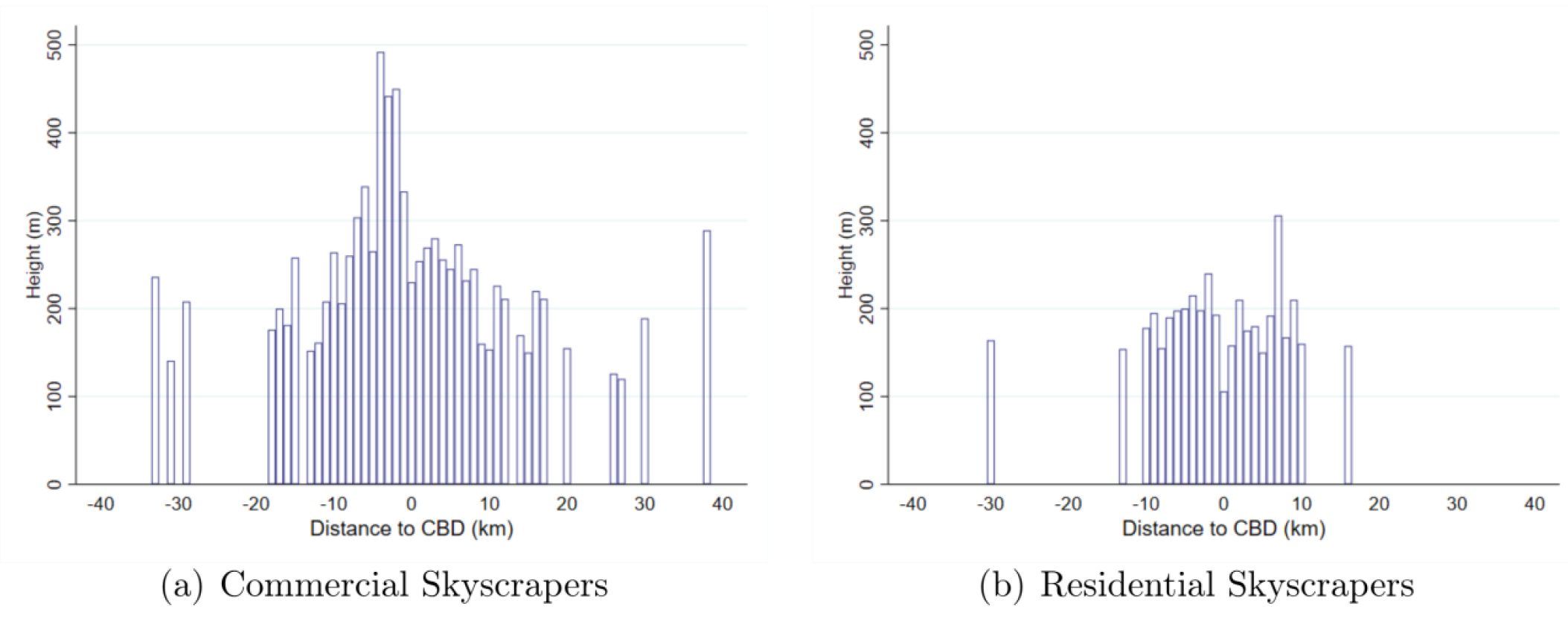

Our analysis reveals two intriguing key patterns in China’s skyscraper development: over half of the commercial skyscrapers are situated in small or mid-sized cities, often far from central business districts, and their heights are less influenced by land costs compared to residential skyscrapers (Figures 1 and 2). This contrasts with trends observed in the US (Ahlfeldt and McMillen 2018).

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of commercial skyscrapers in mainland China, 2006–2014

Figure 2. Distribution of skyscrapers by distance from the CBD, 2006–2014

These patterns challenge the neoclassical theory that skyscrapers are a direct result of land-capital substitution. Instead, an examination of official policy documents reveals a “visible hand” approach, where local governments promote commercial skyscraper development—often in new towns on the urban periphery—to attract skilled labor and high-value firms, aiming to foster productive local agglomerations.

Building on this observation, we employed a spatial matching approach (Chen and Kung 2019) to estimate the magnitude of land discounts by comparing the transaction prices of land parcels designated for commercial skyscrapers with those of adjacent parcels sold within the same year—within radii of 10, 5, and 2.5 km—that shared similar characteristics and thereby comparable market values. We provide evidence that local governments have granted substantial subsidies to commercial skyscraper projects. These subsidies, averaging 40.1% below market rates, primarily support projects in smaller cities or suburban districts, often led by officials motivated by career incentives during periods of credit expansion initiated by the central government.

- Economic returns of skyscrapers

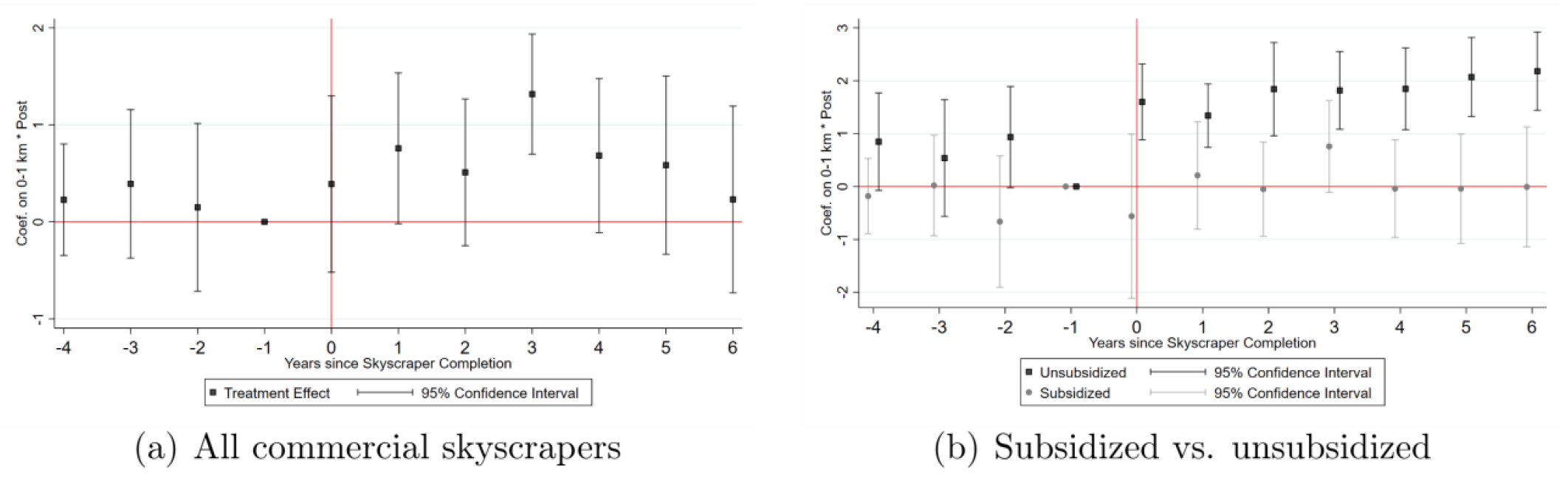

We next evaluate whether the cited economic rationale for providing commercial skyscraper subsidies is substantiated by evidence. Using a spatial difference-in-differences research design, we compare changes in land prices within a two kilometer radius of a newly built skyscraper at the time of completion to those in areas slightly farther away. We find that five to 10 years after completion, subsidized skyscrapers exhibit limited spatial spillovers in terms of land price premiums, new business formation, and urban amenities compared to unsubsidized ones (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Commercial skyscrapers’ impacts on nearby land value

Figure 4. Commercial skyscrapers’ impacts on business formation and urban amenities

- Interpretation

Despite efforts to subsidize the construction of commercial skyscrapers, local governments have not achieved their goal of fostering new urban agglomerations. We propose and assess several plausible explanations for this lack of expected spillover effects. First, the extent of spatial spillovers is closely linked to the location of these skyscrapers. As one of the most durable types of structures, skyscrapers built in suboptimal locations can impose long-lasting costs. These locational disadvantages—or advantages—can be either amplified or mitigated by subsequent infrastructure investments, such as public transit systems.

Second, subsidies may exacerbate the principal-agent problem between local governments and commercial real estate developers. In terms of ex-ante adverse selection, discounted land prices could attract less experienced and financially stable developers. On the other hand, in the context of moral hazard ex-post, the winning bidder for a skyscraper project might lack strong incentives to maximize efficiency once they have received subsidies.

Policy implications and suggestions

Our findings call into question the presumption that heavily subsidizing urban development confers significant benefits, such as attracting businesses and promoting land revenue. One important implication is that the spillovers of grand projects such as skyscrapers are highly dependent on local factors. In our view, the fact that such policies work somewhere does not guarantee that they work everywhere. Moreover, the fiscal motive for placing these projects within large tracts of undeveloped land, and the corresponding lack of supporting infrastructure and subsequent investments, further jeopardize their economic impacts. Moving forward, China’s local governments should prioritize strategic quality over sheer scale by aligning projects with local economic needs and investing in sustainable infrastructure.

References

Ahlfeldt, Gabriel M., and Daniel P. McMillen. 2018. “Tall Buildings and Land Values: Height and Construction Cost Elasticities in Chicago, 1870–2010.” Review of Economics and Statistics 100 (5): 861–75. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00734.

Chen, Ting, and James Kai-sing Kung. 2016. “Do Land Revenue Windfalls Create a Political Resource Curse? Evidence from China.” Journal of Development Economics 123 (November): 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.08.005.

Chen, Ting, and James Kai-sing Kung. 2019. “Busting the ‘Princelings’: The Campaign Against Corruption in China’s Primary Land Market.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134 (1): 185–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy027.

Chen, Ziyang, Ting Chen, Yatang Lin, and Jin Wang. 2025. “Building Tall, Falling Short: An Empirical Assessment of Chinese Skyscrapers.” Journal of Urban Economics 145 (January): 103731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2024.103731.

Wang, Zhi, Qinghua Zhang, and Li-An Zhou. 2020. “Career Incentives of City Leaders and Urban Spatial Expansion in China.” Review of Economics and Statistics 102 (5): 897–911. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00862.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011. “The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4): 1076–1151. https://10.1257/jel.49.4.1076.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email