Can Environmental Regulation Enhance Productivity? Evidence from China’s Industrial Sector

- We study how an environmental regulation implemented in China in the late 1990s impacted firm productivity, finding that productivity increased by 5% on average for regulated firms in less pollution-intensive industries, while remaining stable for those in more pollution-intensive industries relative to unregulated firms.

- Productivity gains are driven by a combination of market selection (i.e., firm exit), reallocation, and intra-firm technology and production process upgrading.

- Creative destruction dynamics are concentrated among privately owned firms rather than state-owned enterprises.

Fostering economic growth and development while protecting environmental quality is a challenge that has long dominated policy and academic discourse. Some argue that environmental regulation can dampen productivity and competitiveness, as it increases costs for firms that must comply. At the same time, regulatory pressure may motivate firms to develop new, more efficient production processes and technologies, which can reduce costs and enhance productivity (Porter and Van der Linde 1995). That is, firm productivity may increase due to innovative activities and substitution of more efficient input (Levinson 2009, 2015; Shapiro and Walker 2018), and if unproductive firms exit, reallocation to more efficient firms throughout the economy may boost aggregate productivity (Syverson 2011).

This “economy versus the environment” tension remains central to the climate policy discourse globally, as many countries are aiming to transition to greener economies without stifling industrial growth. However, evidence as to how environmental policies impact firm productivity remains surprisingly sparse and inconclusive (Dechezleprêtre and Sato 2017, Cohen and Tubb 2018). While a growing body of work demonstrates how some interventions foster green innovation, studies of firm productivity are less common. Most research in this area also has focused on developed countries, but the results may not transfer to developing countries that currently face widespread poverty and poor environmental quality, as they are frequently characterized by different institutional challenges.

We start tackling this question in a recent paper (Lu and Pless 2024) by analyzing the effects of China’s Two Control Zone (TCZ) air pollution regulation on industrial firm productivity. The regulation was introduced in 1998, a period of rapid economic transformation, and it sought to reduce sulfur dioxide (SO₂) emissions by requiring firms in about half of China’s prefectures to adopt pollution-control measures or clean technologies. Although the TCZ regulation was implemented more than 20 years ago, China’s experience provides lessons that are relevant for how other developing and emerging economies at similar growth stages today, like India and Vietnam, might respond to environmental regulations.

Method

Using firm-, industry-, and prefecture-level data from several sources covering 1996 through 2006, we construct firm-level total factor productivity (TFP) and employ a heterogeneous difference-in-differences research design to study how the productivity of firms in regulated prefectures changed relative to those in unregulated prefectures after the regulation was implemented. An important aspect of our approach is that we allow the effects to vary based on whether the firm is in a more versus less pollution-intensive industry, capturing the intensity of “regulatory exposure.” Doing so allows us to estimate the effects not only on firms in the dirtiest industries, but also on those in less dirty industries—those that are still regulated but face lower compliance costs.

Accounting for this heterogeneity is important for understanding the complete picture of how regulation impacts economic activity across all industries. For instance, Greenstone, List, and Syverson (2012) found that productivity declined in U.S. manufacturing following the Clean Air Act, but outcomes varied by pollutant, suggesting that the story of how environmental regulation impacts economic activity is nuanced. Likewise, Metcalf and Stock (2020) highlight sectoral heterogeneity in the effects of carbon taxes.

We address several other potential methodological concerns in our empirical research design as well. For example, we selected the TCZ zones based on the historical air quality of the prefectures, referencing indicators such as ambient SO2 concentrations and precipitation pH values. With this in mind, we control for how firms in prefectures that were already more industrialized may respond differently to the regulation relative to those in less industrialized prefectures with prefecture fixed effects and prefecture-year trends.

Another potential concern is firms moving production to unregulated regions to avoid regulatory costs, which could bias our estimates. That is, multi-plant firms may shift production away from plants in regulated prefectures toward those in unregulated prefectures, or single plant firms may move altogether. However, about 95% of firms in our data are single-plant operations, and relocating large industrial plants altogether is extremely costly. Moreover, if such behavior did emerge, enhanced production by plants in unregulated prefectures should attenuate our results, if anything. We also do not find evidence of high-skilled labor migration in response to the regulation, which could otherwise signal movement of production activities.

Main Findings

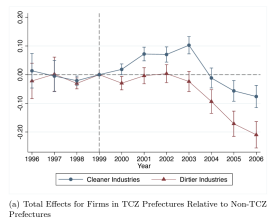

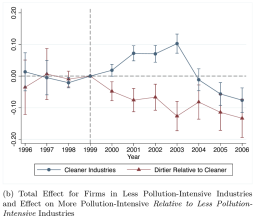

Our results suggest that environmental regulation may be a catalyst for growth under some conditions, although this may hinge upon the strength of underlying institutions and broader market conditions. Figure 1 illustrates our main results:

Productivity increased in firms in cleaner industries relative to unregulated firms. On average, firms in less pollution-intensive industries experienced a 5% increase in productivity compared to their unregulated counterparts (see both panels of Figure 1).

Productivity remained stable for firms in heavily polluting industries relative to unregulated firms. While regulated firms in more pollution-intensive industries saw a decline in productivity compared to regulated firms in cleaner industries (see right panel of Figure 1), their productivity levels remained about the same relative to unregulated firms (see left panel of Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changes in TFP for Firms in More and Less Pollution-Intensive Industries

Mechanisms Driving the Results

Our main results suggest that firms’ responses to the TCZ regulation generated benefits that offset regulatory costs. By carrying out a number of additional tests, we find that productivity improvements are driven by three primary mechanisms:

- Market selection and reallocation: Less productive firms exit while inputs and output—labor, capital, and sales—are reallocated toward more productive surviving firms.

- Within-firm industrial upgrading: Incumbent surviving firms adopted more efficient production processes and modern machinery, reflected by reduced capital age and intermediate input use along with gains in intermediate input productivity. These results are consistent with industrial upgrading and innovative activity that can enhance productivity through a “technique” effect.

- Role of ownership and institutional incentives: Privately owned firms showed stronger responses to regulatory pressure, exiting the market or upgrading production processes. In contrast, state-owned enterprises may have benefited from government protectionism and did not experience comparable productivity improvements.

Implications for Policy and Development

Our findings carry significant implications for policymakers globally, suggesting that environmental regulation need not stifle productivity. In fact, under some conditions, environmental regulation appears to induce innovative activities and more efficient use of resources, which in turn, enhances firm productivity.

For developing economies like India or Vietnam, which are currently undergoing significant economic transformation while simultaneously facing poor environmental quality, China’s experience offers both optimistic and cautionary lessons. Environmental regulation has the potential to catalyze growth, but this may depend on institutional capacity, enforcement, and the incentives for firms to innovate and compete.

Our study also contributes to the broader discourse on industrial policy (see Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik 2023 for a recent review of related academic literature). As debates about green industrial policy gains traction in the U.S., Europe, and beyond, there is revived interest in developing a better understanding of how it might impact economic activity. Although economic growth and environmental regulation are often pitted against each other, our findings suggest that this need not be the case.

References

Cohen, Mark A., and Adeline Tubb. 2018. “The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Firm and Country Competitiveness: A Meta-analysis of the Porter Hypothesis.” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 5 (2): 371–99. https://doi.org/10.1086/695613.

Dechezleprêtre, Antoine, and Misato Sato. 2017. “The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Competitiveness.” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 11 (2): 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rex013.

Greenstone, Michael, John A. List, and Chad Syverson. 2012. “The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Competitiveness of U.S. Manufacturing.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18392. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18392.

Juhász, Réka, Nathan Lane, and Dani Rodrik. 2023. “The New Economics of Industrial Policy.” Annual Review of Economics 16: 213–42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-081023-024638.

Levinson, Arik. 2009. “Technology, International Trade, and Pollution from US Manufacturing.” American Economic Review 99 (5): 2177–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.5.2177.

Levinson, Arik. 2015. “A Direct Estimate of the Technique Effect: Changes in the Pollution Intensity of US Manufacturing, 1990–2008.” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2 (1): 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1086/680039.

Lu, Yangsiyu, and Jacquelyn Pless. 2024. “Greening to Grow: Evidence from Environmental Regulation and Industrial Firm Productivity in China.” MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 6487-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5014283.

Metcalf, Gilbert E., and James H. Stock. 2020. “Measuring the Macroeconomic Impact of Carbon Taxes.” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 110: 101–6. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20201081.

Porter, Michael E., and Claas van der Linde. 1995. “Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate.” In The Dynamics of the Eco-Efficient Economy: Environmental Regulation and Competitive Advantage, edited by Emiel Wubben. Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

Shapiro, Joseph S., and Reed Walker. 2018. “Why Is Pollution from US Manufacturing Declining? The Roles of Environmental Regulation, Productivity, and Trade.” American Economic Review 108 (12): 3814–54. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20151272.

Syverson, Chad. 2011. “What Determines Productivity?” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (2): 326–65. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.2.326.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email