Exports in Disguise: Trade Rerouting during the US-China Trade War?

Our work explores the extent of trade rerouting through Vietnam during the 2018–2019 US-China trade war. We found that the level of rerouting varied significantly depending on the granularity of the measure used: 16.5% of Vietnamese exports to the US were rerouted at the product level, compared to just 1.7% at the firm level. Trade war tariffs led to increases in rerouting, but estimates were again significantly smaller for more granular measures, underscoring the importance of detailed microdata in formulating trade policy and measuring compliance.

Since the US-China trade war began in 2018, global trade flows have shifted dramatically and Vietnam has emerged as a critical player, with increasing imports from China and exports to the US. Policymakers and economists have debated the efficacy of these tariffs, with a major criticism being that they can be evaded via rerouting through third-party countries. This has led many to ask: does “Made in Vietnam” simply mean “Made in China”? However, previous work has conflated rerouting with several legitimate business responses to tariffs.

We explore whether and how Chinese products were rerouted through Vietnam to the US due to the 2018 US-China trade war. The economic dispute started in February 2018 and included several rounds of tariff impositions by the US on Chinese goods and reciprocal tariffs by China on US goods (Bown 2021). During this period, there was significant concern among policymakers that Chinese companies might evade tariffs specific to country origins by redirecting their shipments through third-party nations (Shi and Liu 2019; Kitazume et al. 2019).

There are two main reasons this paper focuses on Vietnam. First, past research indicates that Chinese products are more likely to be rerouted through countries with close ties to China, such as those with geographical proximity, similar institutional frameworks, and shared cultural norms, including the presence of overseas Chinese (Rotunno et al. 2013; Liu and Shi 2019). Given these criteria, Vietnam emerges as a prime candidate for such rerouting activities. Second, among all suppliers of US imports, Vietnam has benefited the most from the decline in US-China trade relations. Research indicates that from 2017 to 2022, Vietnam compensated for nearly half of the market share China lost in US imports (Alfaro and Chor 2023). Additionally, during this period, Vietnam saw a significant increase in its import share from China by 6 percentage points, the largest rise among all its trading partners (Alfaro and Chor 2023).

While the overall trade flows among China, Vietnam, and the US are notable, they alone do not confirm the presence or scale of rerouting. For instance, Vietnamese companies might import raw materials from China and then manufacture different products for export to the US, which is not an act of tariff evasion. This distinction is essential, especially since trade between Vietnam and the US was already expanding before the trade war began (McCaig and Pavcnik 2018). Additionally, the tariffs may have genuinely promoted growth in exports through new foreign investment in Vietnamese companies or increased capital in existing firms.

Our measurement strategy uses two detailed datasets: the Vietnam Enterprise Survey (VES) and S&P Global’s Panjiva (Panjiva). The VES provides data on firm investment, production, capital, employment, revenue, and more. Panjiva details imports and exports at the eight-digit Harmonized System (HS) product level in and out of Vietnam. By combining these sources, we can construct three different measures of rerouting. The first, a product-level measure, captures the movement of specific HS eight-digit products from China through Vietnam to the US within a single quarter. The second, a region-level rerouting measure, captures the same HS eight-digit products flowing in and out of the same Vietnamese province within a quarter. Lastly, a firm-level measure, also considers HS eight-digit products within a quarter, but defines rerouting only as flows through the same Vietnamese firm.

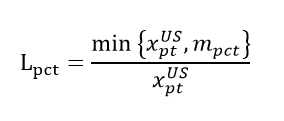

Specifically, for the product-level measure, we compute this object for each HS eight-digit product:

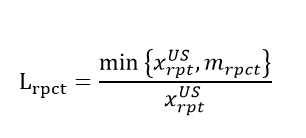

In this equation, p indexes HS eight-digit products, t indexes quarters, and c indexes partner countries. x_pt^US are Vietnamese exports to the US, and m_pct are Vietnamese imports from source country c. When c is set to China, L_pct, our product-level measure of rerouting, captures the maximum possible value of product p flowing from China to the US through Vietnam, normalized by Vietnamese exports of that product to the US. Our region-level measure, L_rpct, follows the same logic, but is also conditioned on each Vietnamese province, which we index using subscript r.

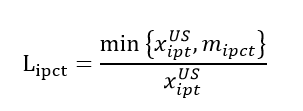

Finally, the firm-level measure, L_ipct, follows the same logic, but is also conditioned on each firm, which we index using subscript i. Note that rerouting could theoretically take place across multiple firms in Vietnam, so we consider this measure a lower bound of true rerouting.

The granularity of our measure significantly influences the estimated extent of rerouting. In 2021, 16.5% of Vietnamese exports to the US were classified as product-level rerouting, in contrast to 6.5% at the regional level and only 1.7% at the firm level. These figures translate to approximately $15.9 billion, $6.3 billion, and $1.6 billion in rerouted goods, respectively.

One other striking pattern emerges in our data. We find that that Chinese-owned firms in Vietnam play a large role in firm-level rerouting. From 2018 to 2021, this group saw the largest increase in firm-level rerouting behavior relative to all other Vietnamese firms that export to the US, with the number of firms engaging in rerouting activity increasing by 314%. It is possible that these firms have unique motivations that drive this behavior as well as institutional knowledge and connections to Vietnamese firms that facilitate it.

We also estimate the causal impact of the trade war on rerouting using temporal variation in tariff implementation, product variation in tariff intensity, and destination variation in tariff targeting. For the average tariff increase on Chinese exports, 12.48%, product-level rerouting increased by 5.9 percentage points, and firm-level rerouting increased by 0.22 percentage points. Given 2018 values, these treatment effects represent a 47.2% increase in product-level rerouting and a 15.7% increase in firm-level rerouting.

Our paper aims to make two contributions. First, it seeks to improve understanding of the US-China trade war's effects on global production. Much existing research has focused on the immediate impacts of tariff increases, showing extensive price transmission and negative economic outcomes in both the US and China (Amiti et al. 2019, 2020; Fajgelbaum et al. 2024; Flaaen et al. 2020; Cavallo et al. 2021; Chang et al. 2021; Ma et al. 2021) as well as the reorganization of global supply chains (Fajgelbaum et al. 2024; Alfaro and Chor 2023; Grossman et al. 2024; Freund et al. 2023). However, there is less empirical data on trade rerouting, partly due to the difficulty of measuring evasion. Our study addresses these gaps and provides estimates for both rerouting levels and their response to tariffs.

Second, we improve on existing methodologies. Much of the previous literature relied on bilateral trade data to measure rerouting, offering inferential evidence (Fisman et al. 2008; Stoyanov 2012; Rotunno et al. 2013; Liu and Shi 2019). For example, studies have shown that China tended to import more through Hong Kong under higher world tariffs. Similarly, evidence of rerouting has been documented where goods receiving preferential treatment under the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement were more likely to be transshipped between the US and Canada, indicating possible violations of origin rules. Other research has looked at how quotas and anti-dumping duties led to correlations between Chinese imports and US exports, particularly in sectors like apparel under the African Growth and Opportunity Act. However, these studies often use product-level data, which might exaggerate rerouting if additional value-added processes within a product category are not visible. Our approach using firm-level data provides a more precise measure of rerouting and allows for a thorough validation with production data.

With Donald Trump’s re-election in 2024, US tariffs on China are likely here to stay. It is therefore critical for businesspeople and policymakers around the world to understand rerouting as they craft their strategies for the coming decades.

References

Alfaro, Laura, and Davin Chor. 2023. “Global Supply Chains: The Looming ‘Great Reallocation.’” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 31661. https://www.nber.org/papers/w31661.

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David E. Weinstein. 2019. “The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (4): 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.187.

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David E. Weinstein. 2020. “Who’s Paying for the US Tariffs? A Longer-Term Perspective.” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 110 (May): 541–46. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20201018.

Bown, Chad P. 2021. “The US–China Trade War and Phase One Agreement.” Journal of Policy Modeling 43 (4): 805–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2021.02.009.

Cavallo, Alberto, Gita Gopinath, Brent Neiman, and Jenny Tang. 2021. “Tariff Pass-Through at the Border and at the Store: Evidence from US Trade Policy.” American Economic Review: Insights 3 (1): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20190536.

Chang, Pao-Li, Kefang Yao, and Fan Zheng. 2021. “The Response of the Chinese Economy to the U.S.-China Trade War: 2018–2019.” Singapore Management University School of Economics, Economics and Statistics Working Paper No. 25-2020. https://economics.smu.edu.sg/sites/economics.smu.edu.sg/files/economics/PG_JobCandidates/YaoKefang/JMP_Yao%20Kefang.pdf.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo, Pinelopi Goldberg, Patrick Kennedy, Amit Khandelwal, and Daria Taglioni. 2024. “The US-China Trade War and Global Reallocations.” American Economic Review: Insights 6 (2): 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20230094.

Fisman, Raymond, Peter Moustakerski, and Shang-Jin Wei. 2008. “Outsourcing Tariff Evasion: A New Explanation for Entrepôt Trade.” Review of Economics and Statistics 90 (3): 587–92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40043169.

Flaaen, Aaron, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot. 2020. “The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines.” American Economic Review 110 (7): 2103–2127. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190611.

Freund, Caroline, Aaditya Mattoo, Alen Mulabdic, and Michele Ruta. 2024. “Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains?” Journal of International Economics 152 (November): 104011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2024.104011.

Grossman, Gene M., Elhanan Helpman, and Stephen J. Redding. 2024. “When Tariffs Disrupt Global Supply Chains.” American Economic Review 114 (4): 988–1029. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20211519.

Iyoha, Ebehi, Edmund Malesky, Jaya Wen, Sung-Ju Wu, and Bo Feng. “Exports in Disguise: Trade Rerouting during the US-China Trade War?” Harvard Business School Working Paper 24-072. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/24-072_a50d1294-e645-4a28-b1f1-ec4e86bd20e4.pdf.

Kitazume, Kyo, Tomoya Onishi, and Yusho Cho. 2019. “Chinese Goods Navigate Alternate Trade Routes to US Shores.” Nikkei Asia, June 1. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Datawatch/Chinese-goods-navigate-alternate-trade-routes-to-US-shores.

Liu, Xuepeng, and Huimin Shi. 2019. “Anti-Dumping Duty Circumvention Through Trade Rerouting: Evidence from Chinese Exporters.” World Economy 42 (5): 1427–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12747.

Ma, Hong, Jingxin Ning, and Mingzhi Jimmy Xu. 2021. “An Eye for an Eye? The Trade and Price Effects of China’s Retaliatory Tariffs on US Exports.” China Economic Review 69: 101685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101685.

McCaig, Brian, and Nina Pavcnik. 2018. “Export Markets and Labor Allocation in a Low-Income Country.” American Economic Review 108 (7): 1899–1941. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141096.

Rotunno, Lorenzo, Pierre-Louis Vézina, and Zheng Wang. 2013. “The Rise and Fall of (Chinese) African Apparel Exports.” Journal of Development Economics 105 (November): 152–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.08.001.

Shi, Huimin, and Xuepeng Liu. 2019. “(Still) Made in China? How Tariff Hikes May Trigger Re-Routing and Circumvention.” VoxEU, July 11. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/still-made-china-how-tariff-hikes-may-trigger-re-routing-circumvention.

Stoyanov, Andrey. 2012. “Tariff Evasion and Rules of Origin Violations Under the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement.” Canadian Journal of Economics 45 (3): 879–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5982.2012.01719.x.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email