Understanding the Evolution of China’s Production and Trade Patterns

China’s role in the global economy has been a topic of intense academic and policy debate. This paper examines the factors driving the evolution of China’s production and trade patterns using firm-level data and a quantitative model. The findings imply that capital accumulation has shifted production toward more capital-intensive industries, and labor-biased productivity growth has allowed China to maintain a competitive edge in labor-intensive sectors. These forces also explain the trajectory of China’s inverted U-shape trade openness, which peaked around the mid-2000s before declining, even though global exposure to Chinese exports rose continuously.

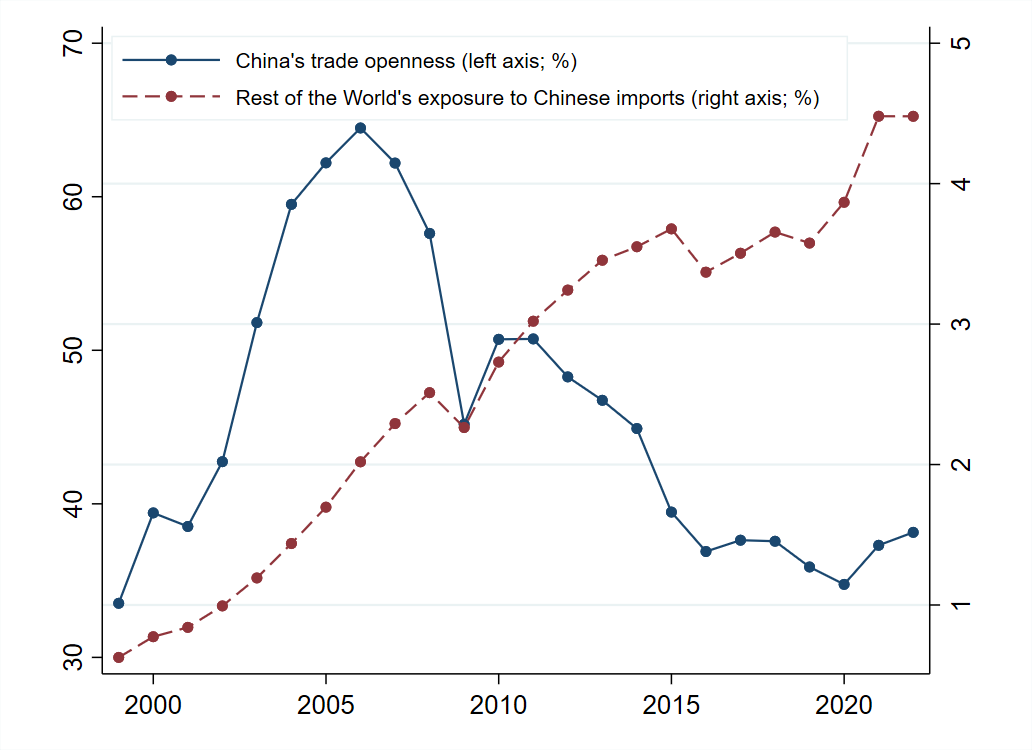

After initially focusing on labor-intensive products like textiles and apparel after its WTO accession in 2001, China rapidly expanded its manufacturing capabilities and is now competing head-to-head with capital-abundant countries in the manufacturing of products like machinery, electronics, and vehicles. Chinese brands like BYD, DJI, and Huawei have become household names in many countries. Such rising competition from China, commonly measured by exposure to Chinese imports (Figure 1), has generated broad debate in academic, policy, and public circles, particularly after the outbreak of U.S.-China trade war (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2014; Bloom, Draca, and Van Reenen 2016; Ju et al. 2024).

Despite the growing concern over the future of China’s trade relationships with the rest of the world (RoW), we know relatively little about how China has gained its current position as a global manufacturing hub. In a recent study (Huang, Ju, and Yue 2024), we delve into the questions of how Chinese production and trade patterns evolve—and why—which are critical to understanding China’s role in the global economic landscape. Our findings suggest that capital deepening, labor-biased productivity growth, and trade costs have played significant roles in reshaping China’s production and trade patterns. The exposure of the RoW to Chinese imports rose continuously because capital accumulation and productivity growth in China outpaced RoW. However, as China becomes more like the RoW in terms of endowments and technology, the scope of comparative advantage declines, and China’s trade openness follows an inverted U-shape pattern (Figure 1).

Figure 1: China’s Trade Openness and the Rest of the World’s Exposure to Chinese Exports

Notes: Trade openness is measured by the sum of exports and imports divided by GDP. The RoW’s exposure to Chinese imports is measured by total Chinese exports divided by the RoW’s GDP (Data source: World Bank).

The Evolution of China’s Production and Trade Patterns

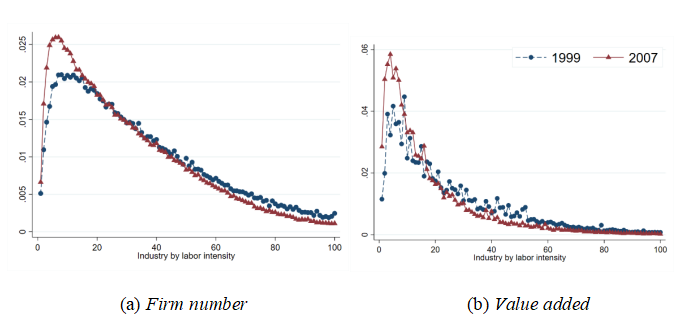

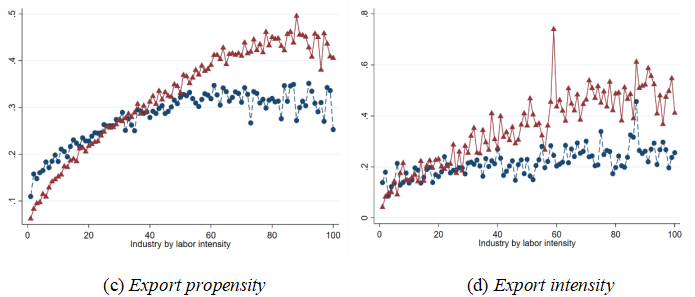

We start the analysis by examining micro firm-level production and trade data from 1999 to 2007 and find counterintuitive patterns of adjustments of Chinese production and trade patterns.[ This sample period was chosen for two reasons. First, it covers the period of China’s trade liberalization since its WTO accession in 2001 and when the rest of the world started to feel the “China shock” (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2013). Second, this is also the period when high-quality Chinese micro firm-level data are available to researchers. We provide results for later periods in the paper.] We find that Chinese production became more capital-intensive over time (Figures 2a and 2b). Nevertheless, we also observe that export participation of labor-intensive Chinese firms increased over time relative to capital-intensive firms (Figure 2c and 2d), while labor intensity is measured by labor cost divided by value added. These patterns contradict the narrative of the classical Heckscher-Ohlin theory, which predicts that as a country becomes more capital-abundant, its production and exports should both become more capital-intensive.

We resolve the puzzle by combining the forces of productivity growth, capital deepening, and trade liberalization in a quantitative trade model. According to our estimated model, capital deepening drives production and export toward sectors like machinery and electronics, traditionally dominated by more capital-abundant countries. Yet, despite this shift, labor-intensive industries have not disappeared. In fact, labor-biased productivity growth provided a counterbalance, keeping China competitive in labor-intensive sectors like textiles. This duality—capital deepening on one hand and labor-biased productivity growth on the other—has complicated traditional views of China’s trade and production transformation. While accumulated capital enables China to diversify into more capital-intensive industries, the country did not lose its comparative advantage in labor-intensive industries thanks to their faster productivity growth, for which we provide various evidence.

Figure 2: Evolution of Chinese Production and Exports, 1999–2007

Notes:Figures (a) and (b) plot each bin's share in the total number of firms and total value added, respectively. Figures (c) and (d) plot the share of exporters and sales exported within each bin, respectively.

The Inverted U-shape of Trade Openness

To get a more complete view of China’s integration with the global economy, we extend the analysis to the year 2017, before the start of the U.S.-China trade war in 2018. We build a general equilibrium model with Ricardian and Heckscher–Ohlin comparative advantage such that countries differ in terms of technologies and endowments, and firms have heterogeneous productivity within each industry. We develop methods to calibrate model parameters until 2017 and conduct simulations to illuminate the effect of different model forces on Chinese production and trade.

The estimated model enables us to understand the inverted U-shape trade openness observed in Figure 1, which peaked around the mid-2000s and has since declined. In particular, we have to examine the interplay between capital deepening, productivity growth, and firm behavior. China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 and trade liberalization led to a surge in exports, especially in labor-intensive sectors, as China leveraged its abundant labor and low production costs. However, as the country accumulated capital and shifted toward more capital-intensive industries, its production resembled more closely that of the RoW, reducing the scope for exploiting comparative advantages. Although labor-biased productivity growth kept labor-intensive industries competitive, as China’s capital-labor ratio and technology levels converged with those of advanced economies, the incentive for firms to export declined. This convergence led to a reduction in trade openness after its peak, despite China’s overall share of global exports continuing to grow due to its rapid economic expansion.

Implications for China’s Future and Global Trade

The nuanced views of China’s trade and production evolution discussed above offer important insights for policymakers, both in China and abroad. For China, the dual forces of capital deepening and labor-biased productivity growth suggest that the country may be able to maintain its competitiveness in labor-intensive industries even as it becomes more capital-intensive. However, as China’s capital-labor ratio and technology levels converge with those of more developed economies, the scope for exploiting its comparative advantage in labor-intensive industries may diminish. Nevertheless, as capital deepening continues, China will gain new comparative advantages in capital-intensive industries. The challenge will be to navigate its transition to a more capital-intensive economy while facing increased backlash from advanced economies.

For the RoW, the continued rise in exposure to Chinese exports, despite China’s declining trade openness, suggests that China’s growing economic scale is having an outsized impact on global trade patterns. This has important policy implications, particularly for countries affected by the “China shock.” The paper’s findings suggest that China’s role in global trade is not static, but rather it is evolving in complex ways that cannot be easily explained by traditional trade models. Policies crafted to address increasing competition with China must take into account the dual forces of capital deepening and technology progress in China beyond trade costs.

References

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68. https://doi.org/0.1257/aer.103.6.2121.

Bloom, Nicholas, Mirko Draca, and John Van Reenen. 2016. “Trade Induced Technical Change? The Impact of Chinese Imports on Innovation, IT, and Productivity.” Review of Economic Studies 83 (1): 87–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdv039.

Huang, Hanwei, Jiandong Ju, and Vivian Yue. 2024. “Accounting for the Evolution of China’s Production and Trade Patterns.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 32415. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32415.

Ju, Jiandong, Hong Ma, Zi Wang, and Xiaodong Zhu. 2024. “Trade Wars and Industrial Policy Competitions: Understanding the US-China Economic Conflicts.” Journal of Monetary Economics 141: 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2023.10.012.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email