Cooperative Culture and the Birth of Modern Enterprises in China

The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed in 1895 and led to the deregulation of Chinese private enterprise investment in state-monopolized industries. Newly founded enterprises necessitated cooperation among member-owners for access to registered capital. A spirit of cooperative behavior thus resulted in the birth of private enterprises in China.

The foundation of enterprises in China hinged on a spirit of cooperation to assemble money through personal networks, employ workers from different regions, and extend business ventures over a great distance (Cochran 2000). Hence, a culture of cooperative behavior played a pivotal role in establishing enterprises (Kalnins and Chung 2006). The signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki (马关条约) in 1895 provides a unique opportunity to quantify the impact of cooperative culture.

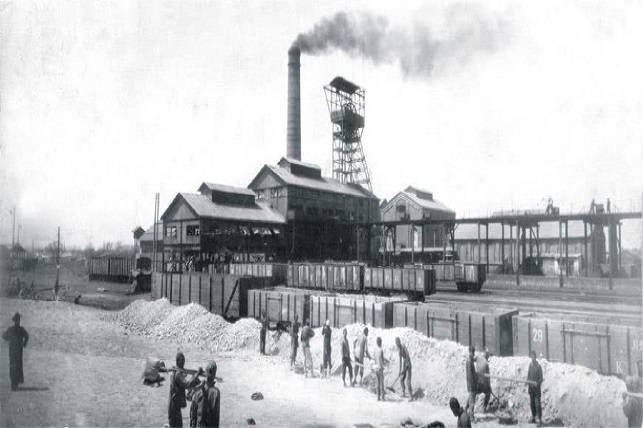

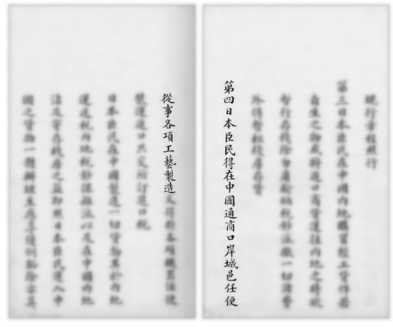

Prior to 1895, as part of the Chinese Qing government’s effort to maintain the base of the state and control the production of commercial goods (like salt), only state-controlled monopolies were allowed to engage in large-scale industrial production. Private enterprises founded before 1895 were constrained by strict authorization and required sponsorship from the Qing government and its agents (Rowe 2009). This regulation of private enterprises began to change after the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, an agreement the Qing government was forced to sign after Japan defeated China in the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95). Under the terms of the treaty (Figure 1), China was obliged to allow foreign corporate capitalism to open factories in its mainland.

Figure 1. Article 4 of the Treaty of Shimonoseki

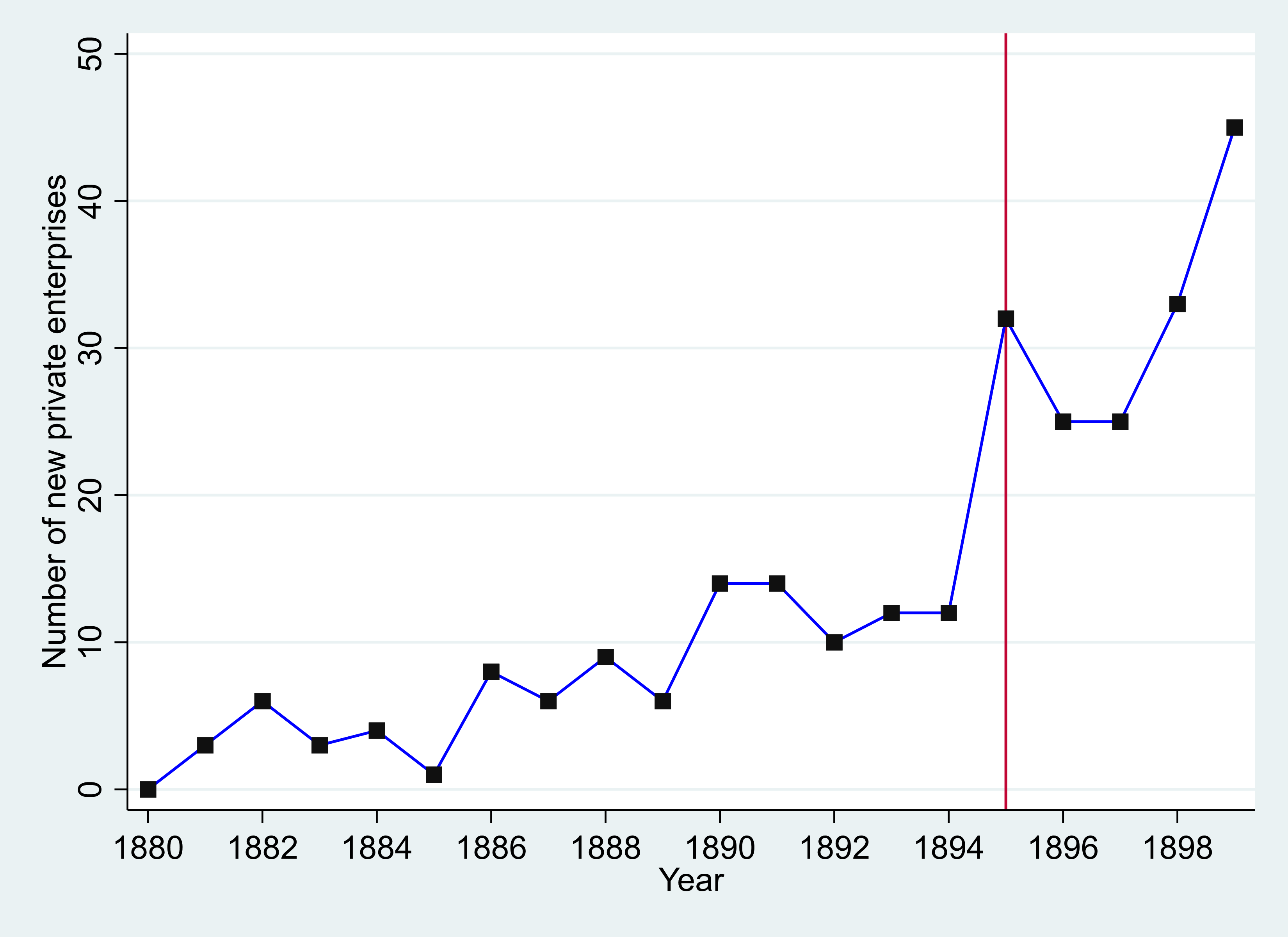

Consequently, foreign companies presented the greatest competition to domestic businesses. As a belated response by the Qing government to prevent Chinese domestic industries, markets, and products from being dominated by foreign enterprises, domestic private enterprises were legally permitted to invest in factories in state-monopolized industries. This deregulation of private enterprises caused a surge in new private enterprises in China from 1895 onwards (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of New Private Enterprises in China, 1880–1899

We collect the data on the number of records on zhaoshang (promoting private businesses, or promoting an environment of doing private business) from the Veritable Records of the Qing Emperors. When the Chinese imperial government deregulated the foundation of private enterprises, we assume that there should be a noticeable expansion in the number of zhaoshang records. Figure 3 shows the number of zhaoshang records for each year from 1850 to 1899, and a sudden increase in 1895, the year the treaty was signed.

Figure 3. Annual Number of New Zhaoshang Records, 1850–1899

Private enterprises run as family businesses were the predominant form of business institutions before the early 19th century. However, unlike the traditional family-based form, modern Chinese enterprises in the late Qing era had already interacted with, and been adapted from, Western business models (Zou 1995, Zhu 2001). Capital demands of these modern enterprises were much larger than family-based enterprises (Zelin 2005). With this background, cooperation inside the issuance process of ownership shares increased access to registered capital. On the whole, a spirit of cooperative behavior among member-owners thus was quite valuable in the early stages of establishing a business, especially for cooperative share enterprises that required cooperation among more capital owners.

A natural question to ask is why certain business cooperative behaviors arose in some places, while others did not? Existing literature argues that cooperative behavior between agents was more likely to occur in regions where the cultures appreciated social interactions (Herrmann, Thöni, and Gächter 2008; Butler and Fehr 2018; Falk et al. 2018).

A line of literature argues that regional variations in cooperative behavior in China are rooted in long-term labor-intensive agricultural practices. As stated by Nisbett (2004) in The Geography of Thought, “Agricultural peoples need to get along with one another… This is particularly true for rice farming, characteristic of southern China and Japan, which requires people to cultivate the land in concert with one another.” Talhelm et al. (2014) proposed the rice theory of culture. They conducted laboratory experiments in China and found that intense cooperation in rice farming over thousands of years had resulted in a collectivistic culture. Rice and wheat are the two main crops cultivated in China, making China a favorable case to identify the relationship between cooperative cultures and the birth of enterprises.

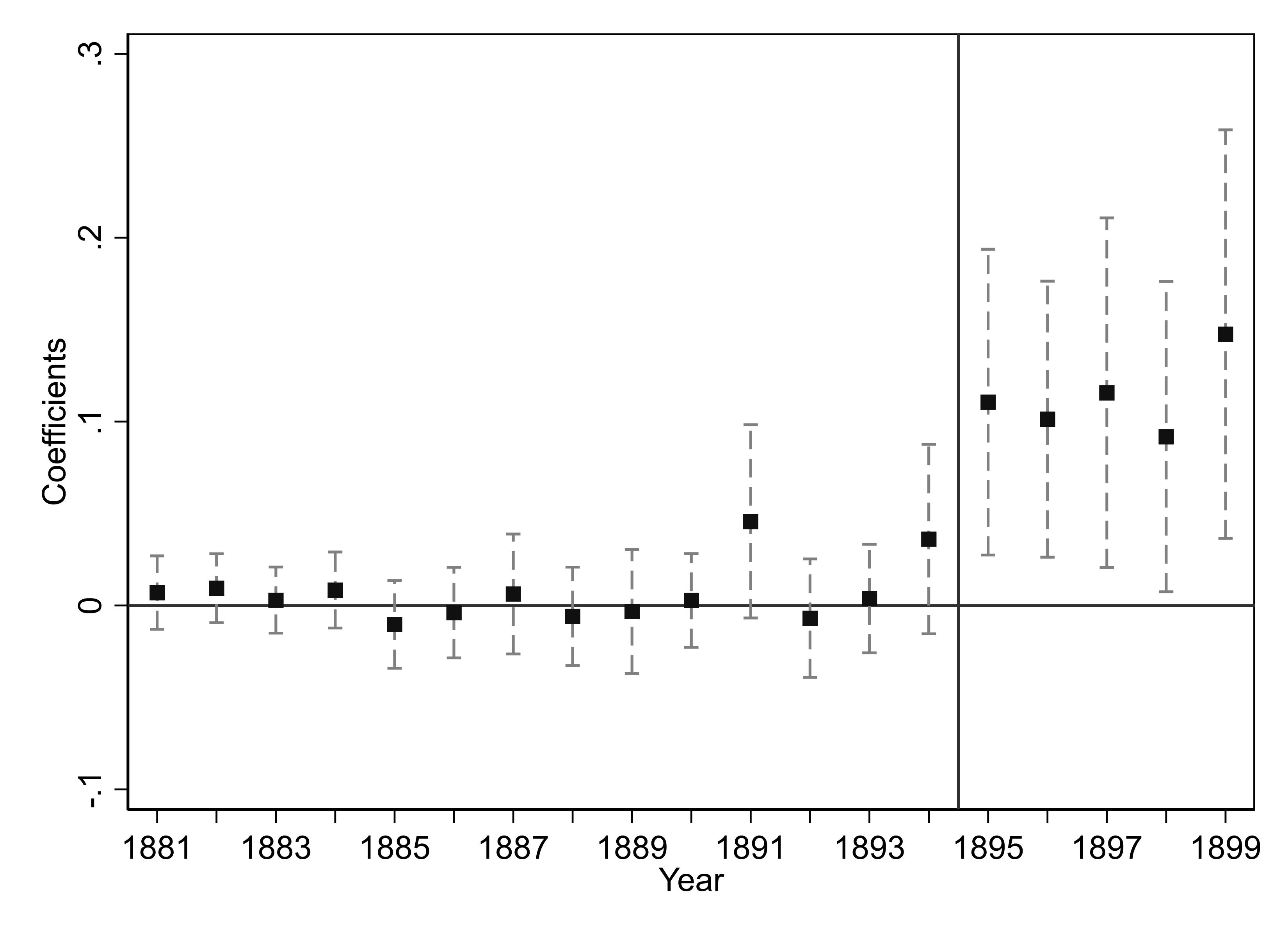

Our estimation shows that after the deregulation of 1895, private enterprises were more likely to be established in prefectures with a higher degree of cooperative cultures (Figure 4). The results are robust when we use alternative measurements for cooperative cultures, sample periods, and accounting for spatial correlations. Furthermore, we found no evidence that any other confounding factors related with rice culture (tight norms and the attitude toward new technology) could explain our baseline findings. A few alternative explanations were ruled out. We also found a long-term effect of cooperative cultures on foundation of enterprises today.

Figure 4. The Dynamic Impacts on the Birth of Enterprises

We highlight the role of culture in fostering the birth of enterprises in a Chinese historical setting. It was the beginning of China’s attempt to create a Western-style corporate system, an effort that continues today. As Chinese enterprises are still dealing with many of the same issues that existed in the late 19th century, our findings suggest that taking cultural traits into account is necessary when starting new businesses and establishing good corporate governance.

References

Butler, Jeffrey V., and Dietmar Fehr. 2024. “The Causal Effect of Cultural Identity on Cooperation.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 223: 134–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2024.03.002.

Cochran, Sherman Gilbert. 2000. Encountering Chinese Networks: Western, Japanese, and Chinese Corporations in China, 1880–1937. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Falk, Armin, Anke Becker, Thomas Dohmen, Benjamin Enke, David Huffman, and Uwe Sunde. 2018. “Global Evidence on Economic Preferences.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (4): 1645–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy013.

Herrmann, Benedikt, Chritian Thöni, and Simon Gächter. 2008. “Antisocial Punishment across Societies.” Science 319 (5868): 1362–67. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153808.

Kalnins, Arturs, and Wilbur Chung. 2006. “Social Capital, Geography, and Survival: Gujarati Immigrant Entrepreneurs in the U.S. Lodging Industry.” Management Science 52 (2): 233–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0481.

Nisbett, Richard E. 2004. The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently . . . and Why. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Rowe, William T. 2009. China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Talhelm, Thomas, Xuemin Zhang, Shigehiro Oishi, C. Shimin, D. Duan, Xuezhao Lan, and Shinobu Kitayama. 2014. “Large-Scale Psychological Differences Within China Explained by Rice versus Wheat Agriculture.” Science 344 (6148): 603–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246850.

Zelin, Madeleine. 2005. The Merchants of Zigong: Industrial Entrepreneurship in Early Modern China. New York: Columbia University Press.

Zhu, Y. 2001. “The First Batch of Joint-Stock Enterprises in Modern China.” Historical Research (5): 19–29. (In Chinese).

Zou, J. 1995. “Shareholding in Modern China.” Historical Archives (3): 100–104. (In Chinese).

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email