Internationalizing Like China

China’s strategy for internationalizing the renminbi involves controlling the access of foreign investors to the domestic bond market. China began by allowing more stable types of investors like central banks to buy RMB-denominated bonds before more recently allowing in flightier types of investors like mutual funds. Through the lens of our theoretical model, we show that investors perceive China’s reputation as a borrower to be in between emerging and developed markets.

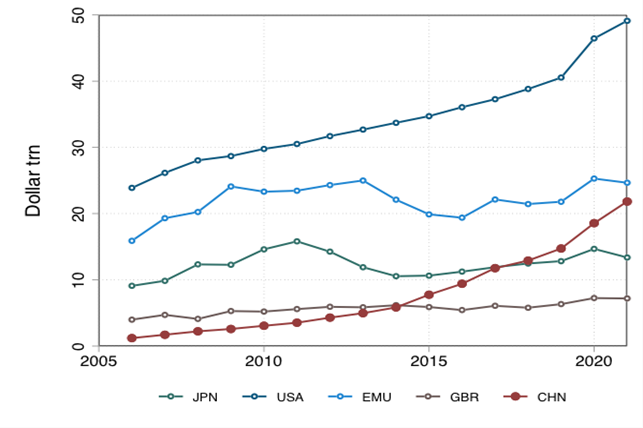

With the third largest domestic bond market in the world, behind the United States and the European Union, China is often described as a possible future international currency provider (Figure 1). However, unlike the US and EU bond markets, the Chinese bond market has been largely closed to foreign investors, severely limiting the use of the Chinese renminbi as an international currency. Over the last decade, that has begun to change, and China has progressively opened its domestic bond market to foreign investment (Amstad and He 2020; Amstad, Sun, and Xiong 2020). While the internationalization process is in its early stages (see also Bahaj and Reis 2020), the size of the market and the ongoing opening-up process make the evolution of China’s bond market an important dynamic at the core of the international monetary system.

Figure 1: Size of Domestic Bond Market. Notional Outstanding. Source: BIS.

Public debate often frames the issue as whether China is about to replace the US as the international currency provider or whether it never will. In “Internationalizing Like China”, we take a step back and carefully document what has actually happened thus far in terms of foreign investment in Chinese domestic bond markets and provide a theoretical framework to think about possible paths for China’s internationalization of its currency.

SELECTING THE FOREIGN INVESTOR BASE

China built the investor base progressively, trading off letting in more investors to build its reputation in global markets with the risk of capital flight. Letting in foreign investors helps build reputation in global capital markets, but letting in too many foreign investors, particularly flighty ones, can be counterproductive by exacerbating crises as the investors pull out in times of stress (as occurred in 2022).

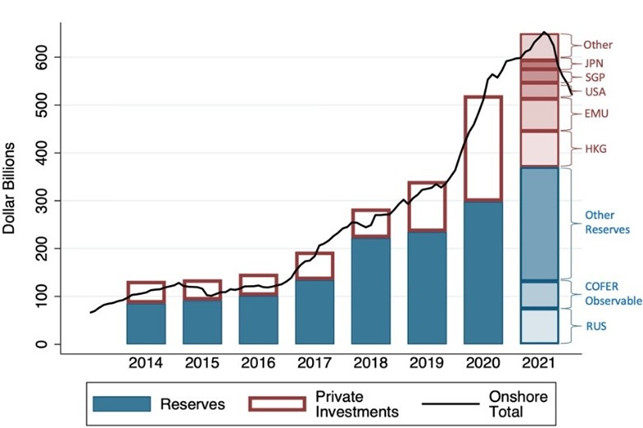

The evolution of investor composition and public or private investors, as well as their geography, is shown in Figure 2. Russia is the largest known holder of official reserves in RMB. The private investor base is broad, with both EU and US investors featuring prominently.

Figure 2: Foreign Ownership of China-Issued RMB Bonds

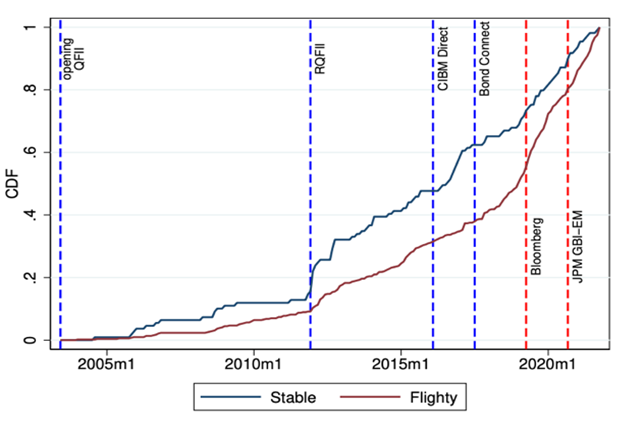

We note that the Chinese government deliberately controlled the entry of foreign investors into its market, first allowing in relatively stable long-term investors like central banks before allowing in flightier investors like mutual funds. Tracking the evolution of investors’ entry in the Chinese bond market, Figure 3 shows the impact of access programs on the investor base. There is a striking difference between the entry pattern for the two types of investors, with stable investors generally entering earlier in the sample period followed by a rapid increase in flighty investors over the most recent years. The 2017 Bond Connect program targeted flightier private investors and was instrumental in the inclusion of Chinese bonds in major world bond indices.

Figure 3: Tracking Flighty and Stable Investor Entry into China’s Bond Market

BUILDING A REPUTATION AS AN INTERNATIONAL CURRENCY PROVIDER

We provide a theoretical framework, based on a dynamic reputation model, to interpret the policy choices of China and think systematically about their likely evolution. We view China’s policy as trading off building reputation as a country capable of providing the global store of value and risking a disruptive foreign capital flight. Letting in foreign investors helps build a reputation for the issuer in global capital markets, but letting in too many foreign investors, particularly flighty ones, can be counterproductive by exacerbating crises as the investors pull out in times of stress (e.g., in 2022).

Crises are costly both directly, because they lead to costly liquidations, and indirectly, because any attempt to limit a flight of capital via ex-post capital controls on outflows leads to a loss of reputation. In our model, the reputation of a government in the eyes of foreign investors is the perceived probability that the government will not impose ex-post capital controls. In practice, this captures investors’ fears of repatriation risk, the possibility that they will not be able to “get their money out of the country.” The expectation that these controls might be imposed is precisely the reputational problem of the country: the more foreigners expect the country to impose the controls ex-post, the worse the terms of credit are ex-ante. This mechanism helps shed light on how a country begins the process of becoming an international currency.

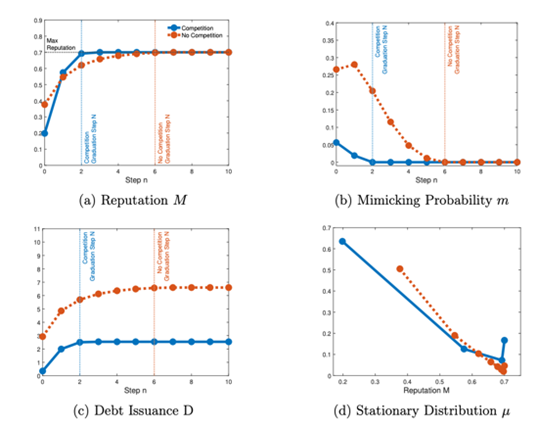

Establishing a reputation as an international currency issuer, like the US, is a slow and arduous process (Eichengreen, Mehl, and Chitu 2017). Throughout modern history, many would-be contenders, like Japan or the EU, have failed to displace the dominance of the dollar. In his Nobel Prize lecture, Sargent (2012) stressed the importance and difficulty of building a reputation for the newly created US in the 1780s and the newly created EU in the 2000s. Whether or not the renminbi will become an international currency is also uncertain. Our model offers a cautionary tale to optimistic views that China might quickly or straightforwardly emerge as an international currency provider. The stationary distribution of the model shows that countries endogenously spend most of the time at low levels of reputation and instituting policies that indeed confirm such low reputation is warranted (Figure 4, panel d). Those governments that trigger the controls lose their reputation with investors, thus resetting their reputation cycle. At low levels of reputation, the cost of losing the existing reputation is also low, thus providing smaller incentives to building a better reputation.

Figure 4: Competition and the Stationary Distribution

Furthermore, reputation can only be built in the fire of a crisis. In normal times, when foreigners do not flee from the country’s debt, the government is not tempted to tamper with foreign

debt holdings. The lack of temptation also means that no reputation is built.

Since crises are infrequent, so are opportunities to build reputation. In this

respect, the behavior of a government during a crisis is a salient moment for

investors to update their beliefs on the type of government they are facing. Each

step in the reputation cycle depicted in Figure 4 might be several years apart.

Investors’ updating is particularly strong for a country like China at the

beginning of the internationalization process because investors are unsure

whether China will resist the temptation to impose controls on capital outflows

in the face of capital flight (Figure 4, panel a). As reputation grows, and

investors assign higher probability that a government will not impose capital

controls, it becomes more difficult to build it and some governments decide

that further gains in reputation are too small to justify not imposing capital

controls in the next crisis. Over the reputation cycle, the debt being issued

increases and at the same time interest rates tend to fall (Figure 4, panel c,

depicts the debt levels). This occurs because a better reputation leads to

improved lender demand for the country’s debt.

TRACKING China’s REPUTATION in markets

Measuring reputation in the data is notoriously difficult. Via the lens of our model, we derive a simple sufficient

statistic to track countries’ reputation over time. It can be estimated in real

time using microdata on foreign investors’ portfolios.

Intuitively, we track whether foreign

investment funds that own Chinese RMB bonds are specialists in investing in

emerging markets or developed market bonds. Formally, we estimate at each point

in time the correlation among investment funds between the share of the foreign

portfolio invested in Chinese RMB bonds and the remaining share invested in a

reference set of safe, developed countries’ government bonds. A higher

correlation points to a country’s reputation closer to the reference set, the

countries of highest reputation.

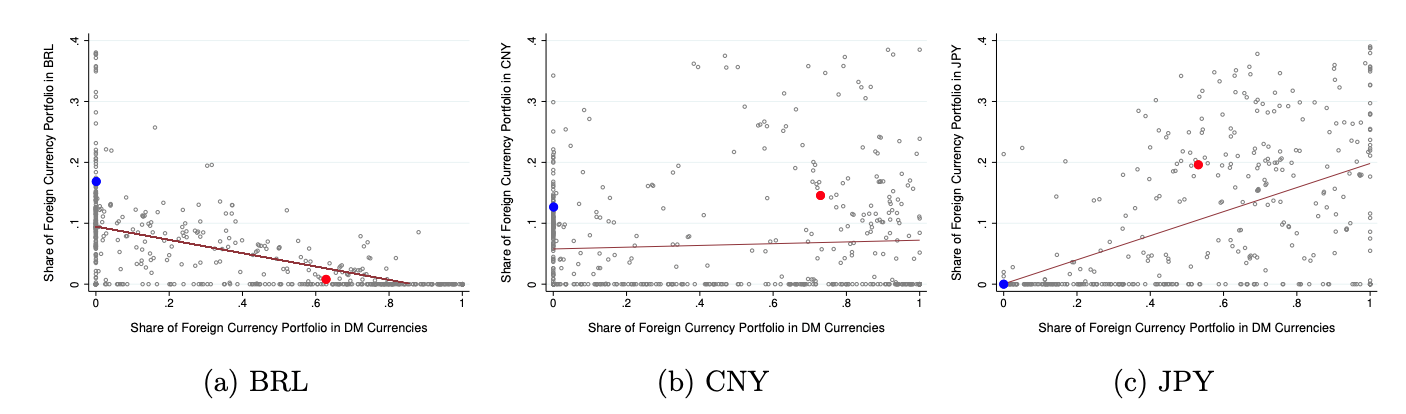

Figure 5 illustrates the measure for

three currencies. Panel a shows that funds with a higher share of their

portfolio in Brazilian real denominated sovereign bonds tend to have a lower

share in bonds issued by developed markets governments in their respective

local currencies. The opposite is true in Panel c, which focuses on Yen

denominated government bonds. These patterns reflect the fact that funds tend

to specialize in investing in either developed or emerging markets. Panel b

shows that CNY denominated government bonds are in between: they are held by both

funds specializing in emerging markets and those specializing in developed

markets.

Figure 5: Portfolio Shares by Currency, December 2020

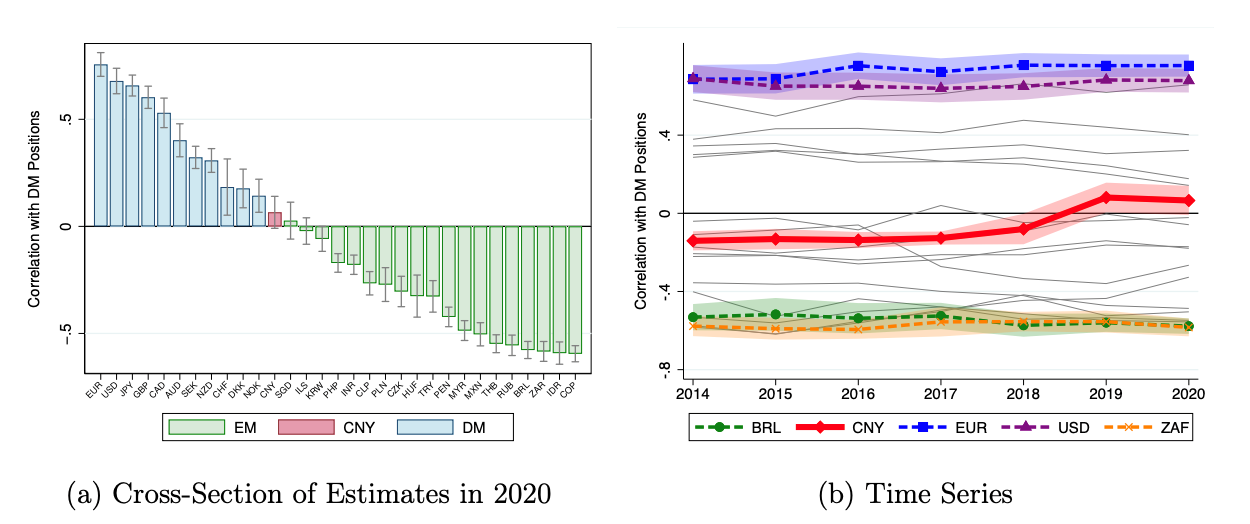

Figure 6 shows more generally that China’s reputation is in between that of emerging markets and developed countries and has drifted somewhat upwards in recent years. Interestingly, the move up in reputation has coincided with reforms and opening up to flightier foreign investors. It remains to be seen how this measure will evolve in the future as crises, capital outflows, and policy choices occur.

Figure 6: Measuring Countries Reputation in Bond Markets

COMPETITION WITH THE US

Competition from established reserve currency issuers like the US can also deter a new entrant like China from building a reputation. Established issuers can attempt to flood the market with safe assets, thus satiating investor demand. This reduces the rents that new entrants could earn by building reputation, their perspective “exorbitant privilege,” thus undercutting their incentives to build reputation. Indeed, Figure 4, panel d shows that moving from a model with no competition among the issuers (red dotted line) to one with competition (blue solid line) shifts the stationary distribution of the model to feature lower reputation levels and countries that endogenously spend more time at these low reputation levels. For the US, of course, flooding the market with safe assets is easier said than done, since higher borrowing may itself raise questions about the safety of US treasuries.

References

Amstad, Marlene, and Zhiguo He. 2020. “Chinese Bond Markets and Interbank Market.” In The Handbook of China’s Financial System, edited by Marlene Amstad, Guofeng Sun, and Wei Xiong, 105–50. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Amstad, Marlene, Guofeng Sun, and Wei Xiong. 20202. The Handbook of China’s Financial System. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bahaj, Saleem, and Ricardo Reis. 2020. “Jumpstarting an International Currency.” SSRN Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3627739.

Clayton, Christopher, Amanda Dos Santos, Matteo Maggiori, and Jesse Schreger. 2022. “Internationalizing Like China.” SSRN Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4055583.

Eichengreen, Barry, Arnaud Mehl, and Livia Chitu. 2017. How Global Currencies Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sargent, Thomas J. 2012. “Nobel Lecture: United States Then, Europe Now.” Journal of Political Economy, 120 (1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/665415.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email