Serial Entrepreneurship in China

New firms have been an important engine of growth in the Chinese economy (Brandt, Van Biesebroeck, and Zhang 2012). Drawing on data on the universe of all firms in China, we study entrepreneurship and the creation of new firms in China through the lens of entrepreneurs who operate a series of firms over their lifetime, i.e., serial entrepreneurs (SE). In principle, their advantage over non-serial entrepreneurs may lie in their ability to identify new business opportunities and superior productivity; alternatively, it may rest in connections providing better access to scarce factors such as finance that facilitate entry. We find that ability is a major driver of serial entrepreneurship and that firms run by SEs are more productive. However, capital constraints are key to explaining the choice to operate these firms concurrently or sequentially. Risk diversification and the value of upstream/downstream linkages figure prominently in sectoral choices, conditional on the sector of the SE’s first firm.

Serial Entrepreneurs

A small number of studies for other countries document that upwards of one-quarter of all firms are started by serial entrepreneurs (Lafontaine and Shaw 2016; Hyytinen and Ilmakunnas 2007; Amaral, Baptista, and Lima 2011; Rocha, Carneiro, and Varum 2015; Carbonara, Tran, and Santarelli 2020). Studying serial entrepreneurs, however, is often constrained by data availability. One needs data capturing entrepreneurial activity of individuals over their lifetimes as well as data on the outcomes of these firms.

In this paper, we leverage two unique data sources for Chinese firms to examine serial entrepreneurship: the Business Registry of China, which includes information on every firm ever operated in China, and the Inspection Database. Through unique identifiers for the main owner(s) of each firm at the time of establishment, we can identify serial entrepreneurs. The registry also provides information on firm location and sector. The inspection database, which runs from 2008 to 2012, provides annual information to calculate firm TFP, debt, equity, and capital.

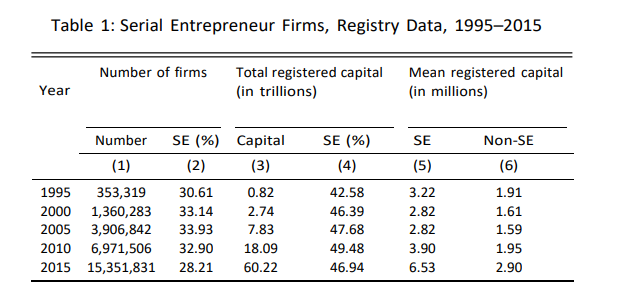

Table 1 provides summary information for select years on the number of firms in China and their registered capital. Firms established by serial entrepreneurs consistently represent one-third of all firms and have almost half of the total registered capital. On average, they are also two times larger in terms of registered capital. A key message from Table 1 is that firms run by serial entrepreneurs are a key driver of firm performance in China.

Notes: Authors’ calculations are from Business Registry data. SE stands for serial entrepreneur firms. Capital is calculated based on the registered capital in a firm.

Explaining Serial Entrepreneurship: The Role of Equity vs. Ability

Operating a firm requires capital, and entrepreneurs can use either their own equity or borrow to start a new firm. In settings such as China, however, borrowing is often limited by collateral constraints that allow entrepreneurs to collateralize only a fixed fraction of the capital stock.

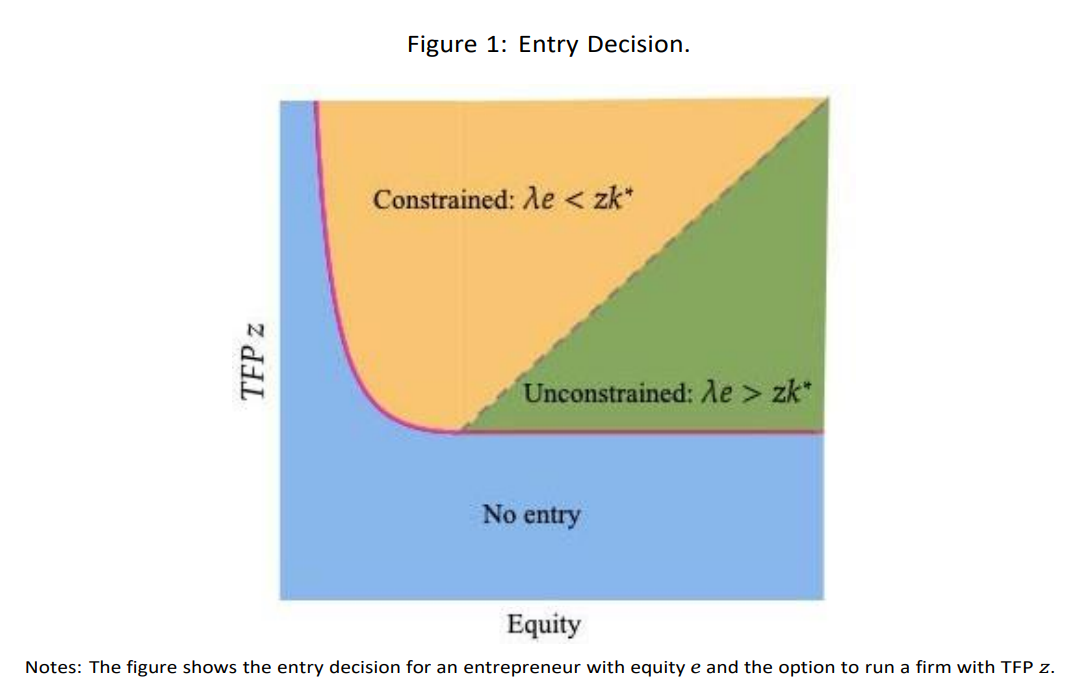

Consider the first period of a simple two-period model of firm creation in which potential entrepreneurs receive the option to start a new firm each period with stochastic productivity, z1. Potential entrepreneurs also differ in terms of their endowment or equity, e. Based on their equity and ability, entrepreneurs fall into one of three regimes: no entry, capital constrained, and unconstrained. In Figure 1, the solid line z1∗(e) marks the indifference between entry and no entry. The entrepreneur chooses to operate the firm if and only if TFP is sufficiently large. The function z1∗(e) is falling in the level of equity e, implying that a larger e is associated with a (weakly) lower threshold z1∗(e). Among those for whom it is profitable to enter, the dotted line demarcates the capital constrained and unconstrained entrepreneurs.

The theory has immediate implications for the allocation of capital and debt across firms. Both installed capital and debt should be larger for more productive firms because it is optimal to install more capital in firms with higher TFP. High-TFP firms are therefore more likely to be debt financed.

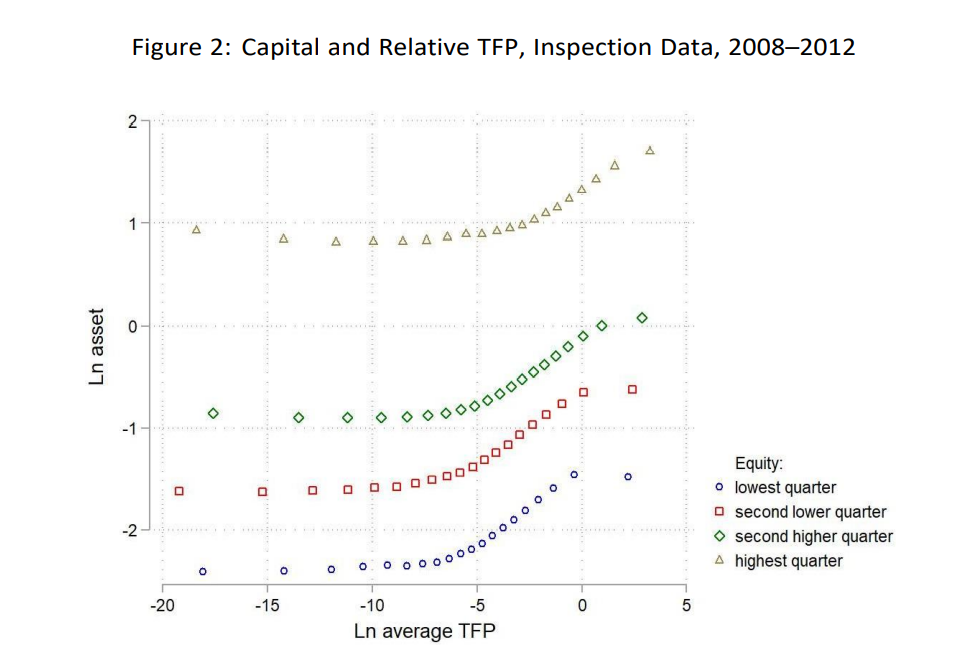

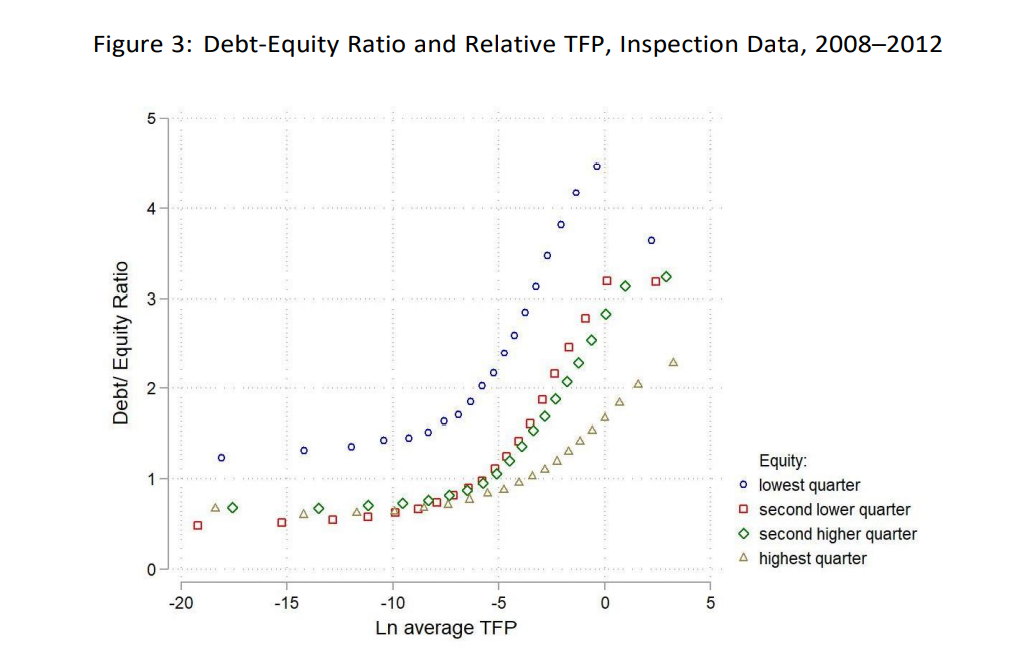

Installed capital should also be higher in firms with more equity. Figures 2 and 3 show that the data for Chinese firms conform tightly with these predictions.

At the beginning of the second period, an entrepreneur with equity e receives the opportunity to start a second firm with productivity z2. In addition, those entrepreneurs who started and operated a firm in the first period may continue to do so in the second. An entrepreneur may choose to operate zero, one, or two firms in the second period. How do SEs compare to non-serial entrepreneurs?

The relative productivity of serial entrepreneurs is shaped by a fundamental trade-off between the persistence of skills across firms of an individual entrepreneur and differences between entrepreneurs in their non-skill advantages at starting firms. The latter could include preferential access to key inputs, obtaining a business license, etc. If skills are sufficiently persistent and potential entrepreneurs are identical except for the initial draw of TFP, the first firm started by a SE should be on average more productive than other firms in the same industry, and the second SE firm should be even more productive. The reasoning is straightforward: serial entrepreneurs are positively selected on TFP. On the other hand, if the persistence of skills is sufficiently low and some entrepreneurs have large non-skill advantages, serial entrepreneurs should have lower TFP than non-serial entrepreneurs since serial entrepreneurs are selected on traits other than TFP.

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the Inspection Database. The figure shows the relationship between the debt-equity ratios and TFP. Firms are sorted into four quarters according to their equity. For each equity quarter, firms are ranked on TFP and sorted into twenty ventiles. Each point in the figure plots log average TFP and average debt over average equity for firms in the ventile. All variables are computed relative to their averages of all firms in the same province-industry-year cell.

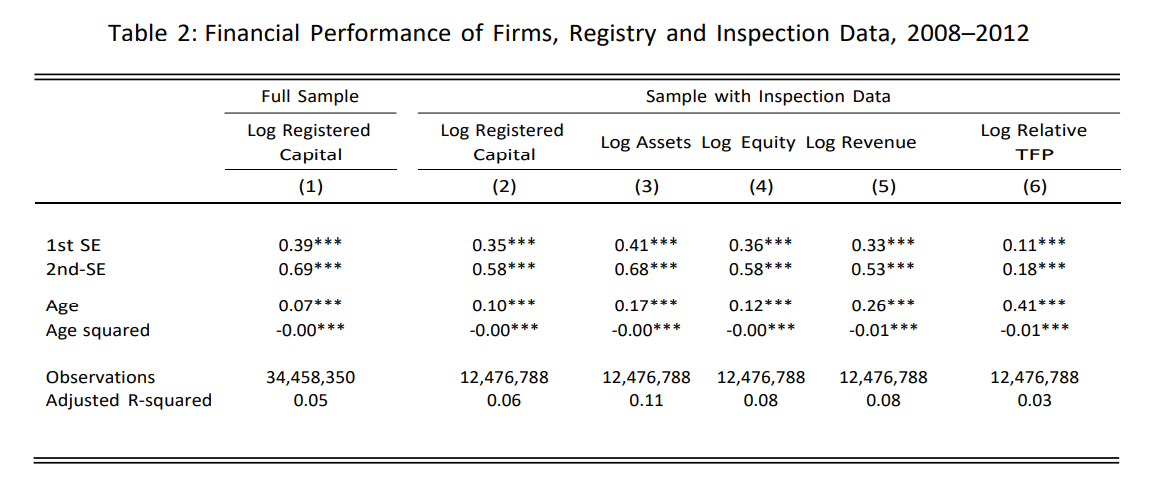

Table 2 compares first and second SE with non-serial firms. Consistent with Table 1, serial firms are larger in terms of assets, equity, and revenue, but they are also better. Compared to other firms in the same industry and locality, the first SE firm is significantly more productive, and the second SE firm is even more productive. Relative to their peers, the first and second SE firms are 11.6% and 19.7% more productive, respectively.

Firms started by SEs can be operated concurrently or sequentially, i.e., old firms are closed when new firms are established. Our theory predicts that entrepreneurs who have more capital and/or a more productive first firm are more likely to operate firms concurrently. Moreover, SEs with firms that have relatively similar TFP are also more likely to run them concurrently. Conversely, SEs with a larger gap in TFP between firms—one firm being substantially more productive than the other—are more likely to run these firms sequentially due to a larger opportunity cost of capital. These predictions are borne out in the data.

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the Inspection Database. The figure shows the relationship between the debt-equity ratios and TFP. Firms are sorted into four quarters according to their equity. For each equity quarter, firms are ranked on TFP and sorted into twenty ventiles. Each point in the figure plots log average TFP and average debt over average equity for firms in the ventile. All variables are computed relative to their averages of all firms in the same province-industry-year cell.

Sectoral Choices of SEs

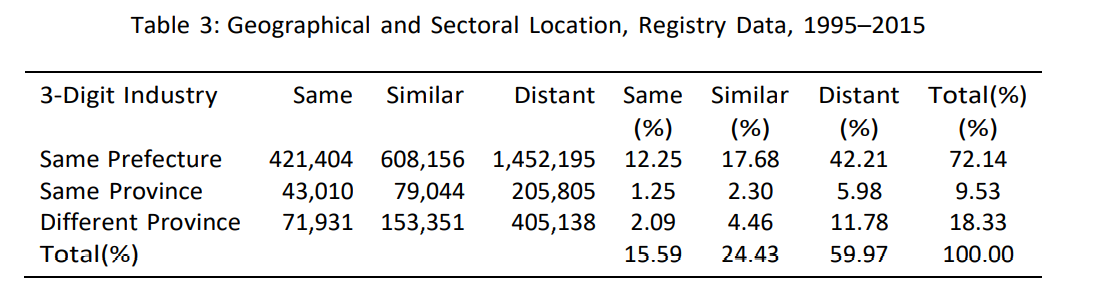

An important decision of entrepreneurs is which sector to enter. We find relatively small differences in the unconditional choice of sectors of serial and non-serial entrepreneurs.However, in 60%of the cases, serial entrepreneurs start their second firm in a “distant” sector, defined here as different at the one-digit level from their first firm. In contrast, they start 72% of their second firms in the same prefecture as the first. Table 3 provides the breakdown by geographical and sectoral location.

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the Registry Data. Industries are similar if they have the same 1-digit, but different 3-digit, codes. Industries are distant if they have a different 1-digit code.

We examine several alternative explanations for these choices including: selection by learning about entrepreneurial abilities, risk diversification, and upstream-downstream sectoral linkages and input-output complementarities. Selection by learning ties the entrepreneur’s choice of sector for the second firm to their productivity in the first firm—if the TFP of the first SE firm is sufficiently high, for example, entrepreneurs will remain in that sector; for lower values, they move to more distant sectors. Following Williamson (1975), ownership in upstream-downstream sectors as well as those with input-output complementarities may help mitigate information asymmetries and transaction costs.

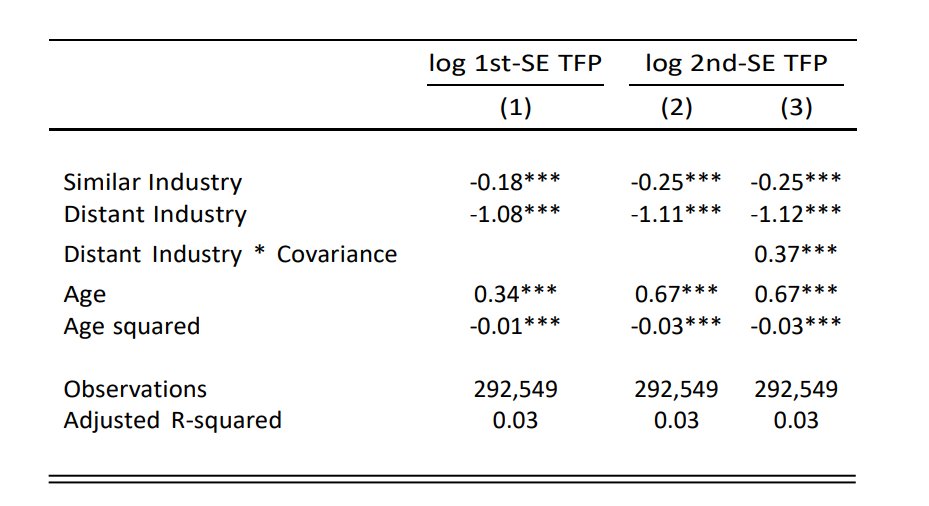

Table 4 reports the TFP for first and second SE firms conditional on industry (sector) choice. Our estimates imply that first and second SE firms are three times more productive when both firms are in the same three-digit sector compared to SE firms in distant sectors. Furthermore, the TFP for the first and second firms are 19.7% and 28.4% higher, respectively, when both firms are in the same three-digit sector compared to SE firms in the same one-digit sector, but different three-digit sector. This ranking of TFP is consistent with the view that the TFP of these entrepreneurs is highly persistent.

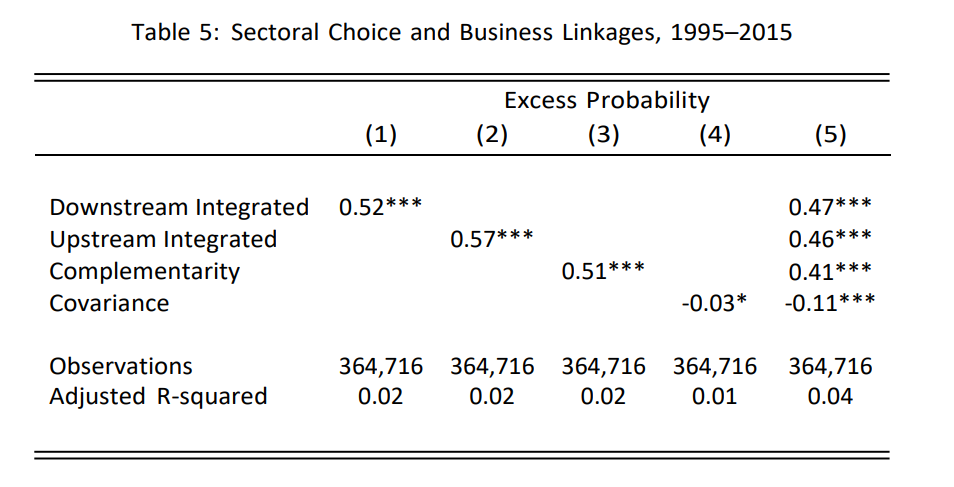

Table 5 reports regressions of a normalized measure of starting the second firm in sector j given that the first SE is in sector i on downstream and upstream linkages, sector complementarity, and a measure of covariance of returns between the two sectors. Serial entrepreneurs are much more likely to start firms in sectors in which these linkages are more important, and sectors in which the covariance in returns is smaller.Given lower productivity in more distant sectors, our findings hint at important trade-offs in the sectoral choices of serial entrepreneurs.

Table 4: TFPs for First and Second SE Firms, Conditional on Industry, Inspection Data, 2008–2012

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the Inspection Database. First and second SE firms are identified from the Registry. The table compares the TFP of first SE (second SE) firms that are in the same three-digit industry, relative to first SE (second SE) firms that are in similar or distant three-digit industries. Industries are similar if they have the same one-digit, but different three-digit, codes. Industries are distant if they have a different one-digit code. TFP is computed relative to the averages of all firms in the same province-industry-year cell. The variable covariance is the covariance of the return of assets between each two sectors. This variable is standardized to have mean zero and a standard deviation of one. The notation ∗∗∗ signifies statistically significance at the 1% level.

Conclusion

Serial entrepreneurs are quantitatively important in China. Our finding that ability is a major driver of their success makes them fundamental to China’s economic dynamism. Significant differences exist, however, in the business environment in which entrepreneurs operate (Brandt, Kambourov, and Storesletten 2019). These differences can influence selection into entrepreneurship and the properties of serial entrepreneurs, including their relative productivity. In future work, we plan to explore these differences and their implications for regional economic development in China.

References

Amaral, A. Miguel, Rui Baptista, and Francisco Lima. 2011. “Serial Entrepreneurship: Impact of Human Capital on Time to Reentry,” Small Business Economics 37: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9232-4.

Brandt, Loren, Ruochen Dai, Gueorgui Kambourov, Kjetil Storesletten, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2022. “Serial Entrepreneurship in China.” Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. DP17131. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4069940.

Brandt, Loren, Gueorgui Kambourov, and Kjetil Storesletten. 2020. “Barriers to Entry and Regional Economic Growth in China.” Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. DP14965. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3650077.

Brandt, Loren, Johannes Van Biesebroeck, and Yifan Zhang. 2012. “Creative Accounting or Creative Destruction? Firm-Level Productivity Growth in Chinese Manufacturing.” Journal of Development Economics 97 (2): 339–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.02.002.

Carbonara, Emanuela, Hien Thu Tran, and Enrico Santarelli. 2020. “Determinants of Novice, Portfolio, and Serial Entrepreneurship: An Occupational Choice Approach.” Small Business Economics 55: 123–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00138-9.

Hyytinen, Ari, and Pekka Ilmakunnas. 2007. “What Distinguishes a Serial Entrepreneur?” Industrial and Corporate Change 16 (5): 793–821. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtm024.

Lafontaine, Francine, and Kathryn Shaw. 2016. “Serial Experience: Learning by Doing?” Journal of Labor Economics 34 (S2), S217–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/683820.

Rocha, Vera, Anabela Carneiro, and Celeste Amorim Varum. 2015. “Serial Entrepreneurship, Learning by Doing and Self-Selection.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 40 (May), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2015.04.001.

Williamson, Oliver E. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies. New York: Free Press.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email