Does ESG Travel around the World? Evidence from Multinational Firms in China

Using a sample of 3,770 Chinese listed firms during 2015–2020, we find that firms’ ESG ratings increase with foreign sales ratios. The higher-rated multinationals have more foreign subsidiaries located in countries with better ESG conditions, and their equity shares are held to a greater extent by institutional investors, especially by foreign institutions. The multinationals’ higher ESG ratings can be justified by higher expenditures on green investment and superior access to green credits. Our analysis suggests that international business can help promote the ESG performance for firms in emerging markets.

Despite investors’ increasing attention to companies’ performance in Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG), it is still unclear how investors should interpret a firm’s ESG rating. Edmans (2020) argues that in addition to the ESG rating of a company, investors need to understand what the ESG rating actually captures. In Hu and Li (2021), we examine whether a firm’s ESG rating is affected by the firm’s foreign business. As much as the concept of ESG has received global popularity, less is known whether ESG practices are globally integrated. How do foreign countries’ ESG conditions shape multinational firms’ ESG practices? Can a firm’s foreign ESG practices be captured by ESG ratings? Is ESG globally promoted through a firm’s international business?

Multinational firms may have different ESG performance from domestic counterparts for several reasons. First, the strictness of ESG-related policies varies significantly across countries (Ben-David et al. 2018). Compared with domestic firms that are only subject to the home countries’ policies, the practices of multinational firms are shaped by the policies of multiple countries where the foreign subsidiaries are located. Whether a multinational engages more in ESG practices than a domestic firm depends on the foreign countries’ policies. As the ESG policies of a foreign country are tightened, multinationals need to ensure that the ESG practices of their subsidiaries in that country keep pace with that country’s new standards. Therefore, we predict that multinationals’ ESG ratings may increase with the ESG standards of the foreign countries where their subsidiaries are located, ceteris paribus.

Second, developed countries overall have higher ESG standards than emerging countries. According to the 2020 Country Risk Ratings issued by Sustainalytics, a Morningstar company that assesses the environmental, social, and governance factors of worldwide countries, among the top 20 countries with the highest ESG scores only one comes from the emerging markets (Brunei Darussalam, ranked 19th). Among the countries where the foreign subsidiaries of Chinese listed firms are located, Switzerland ranks first in environment (E), Denmark ranks first in social (S), and Finland ranks first in governance (G). All these countries are from developed markets. Thus, it is likely that firms headquartered in emerging markets may have higher ESG ratings if they have increased business transactions with developed countries.

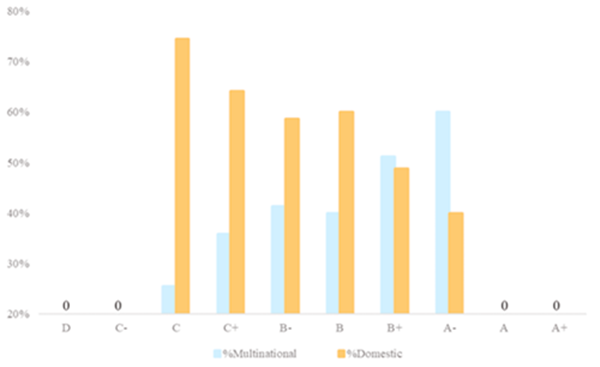

Using a sample of 3,770 A-Share listed firms during 2015–2020, we find that a firm’s ESG rating increases with its foreign business exposure. Specifically, a one-standard deviation-increase in a firm’s foreign sales ratio is associated with an 11.7% increase in the firm’s ESG ratings. Figure 1 plots the distribution of ESG ratings for the domestic and multinational firms. We can see that more multinationals receive a rating of B or higher, while more domestics receive a rating of B or lower.

Figure 1: ESG Rating Distribution of Multinational Firms

Note: This figure plots the proportion of multinational firms and domestic firms for each grade of ESG rating during 2015–2020. The ESG sample ratings are provided by SynTao Green Finance (STGF), one of the largest data providers of ESG performance of Chinese firms. The light blue bars represent the proportion of multinational firms over all nonfinancial and non-ST listed firms in each grade. The orange bars represent the proportion of domestic firms in each grade. We marked 0 at D, C-, A, and A+, because no firm in our sample is rated with these grades from 2015–2020.

Next, we evaluate the ESG conditions of the countries where the multinationals’ subsidiaries are located. Presumably, if multinational firms earn higher ESG ratings because they undertake more ESG activities to satisfy the requirements of the foreign countries, we should expect that the multinational firms’ ESG ratings would increase with the business exposure in the ESG-oriented countries. We find that the sensitivity between a firm’s foreign business exposure and ESG ratings becomes stronger when the firm has a greater fraction of foreign subsidiaries located in countries with less environmental pollution, better social responsibility, and better public governance.

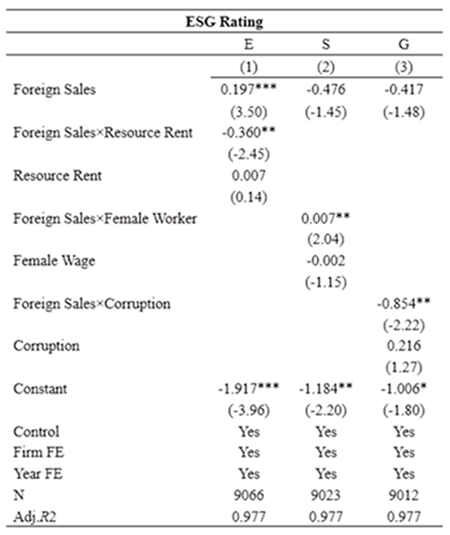

Specifically, as shown in Table 2, the sensitivity between a firm’s foreign sales ratios and its ESG ratings becomes significantly stronger as the foreign countries have less resource rent (–0.360*), higher ratios of female workers (+0.007**), and lower corruption perception (–0.854**). The results hold robust using alternative proxies of ESG conditions. The results suggest that the multinationals’ higher ESG ratings are driven by the higher ESG standards in the countries of the firms’ foreign subsidiaries. Not surprisingly, for domestic firms (Fsp. = 0) there is no significant relation between foreign countries’ ESG conditions and their own ESG ratings.

Table 2: Multinationals’ ESG Ratings and Foreign Countries’ ESG Conditions

Note: The table reports the estimates on the role of foreign countries’ ESG conditions in the relation between foreign sales and the firms’ ESG ratings. Environmental conditions are measured by Resource Rent, the value of capital services flows rendered by natural resource extractions divided by annual GDP. Social conditions are measured by Female Worker, the ratio of contract female workers over male workers. These data are provided by World Bank. Governance conditions are measured with Corruption, the corruption perception index provided by Transparency International. Standard errors are clustered at the industry level and the t-statistics are in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Financial markets have been recognized as an effective external mechanism that disciplines corporate governance. To the extent that ESG-rating agencies refer to the professional judgment of practitioners in financial markets to determine ESG ratings, we should expect that firms’ ESG ratings should be associated with the firms’ exposure to financial markets. We find that a firm’s foreign business exposure and its ESG rating become more positively associated when the firm has more analyst coverage and more institutional ownership, and a multinational firm earns higher ESG ratings when the firm has higher ratios of foreign institutional ownership, which is consistent with Aggarwal et al. (2011) that international portfolio investment by institutional investors promotes good corporate governance practices around the world.

One obvious question is whether the ESG rating in fact reflects actual ESG practices? In our study, we compare the green activities between multinational firms and domestic firms, and find that the multinational firms have significantly more expenditures on green investment and more credit allocations from green commercial banks in China. Such differences reasonably explain the rating differences. Therefore, it appears that the firms’ ESG ratings can be justified by actual ESG practices.

One possible concern about the multinational firms’ higher ESG ratings is that multinational firms are in nature more ESG-oriented. These firms may find it easier to establish subsidiaries in ESG-oriented countries. To address this self-selection issue, we investigate whether a multinational firm’s decision to establish foreign subsidiaries is affected by the differences in the ESG conditions between China and the foreign countries. The results show that these two factors do not seem significantly correlated, mitigating the concern about the endogenous selection of subsidiary locations.

Our paper is related to three strands of literature, the first being that of the determinants of ESG ratings. Existing studies have shown that rating agencies disagree substantially on companies’ ESG performance, and it is crucial for investors to understand which metrics are evaluated and how they are assessed (Chatterji et al. 2016; Gibson, et al. 2020; Berg et al. 2020; Edmans 2020). The second literature strand to which we relate is that on corporate governance of multinational firms. Regarding multinational firms’ ESG practices, Ben-David et al. (2021) show firms headquartered in countries with strict environmental policies transport their polluting activities abroad to countries with relatively weaker policies. In this paper, rather than examining firms’ strategies in response to regulations, we investigate how foreign countries’ ESG conditions affect multinationals’ ESG practices. The third area we relate to is that of the discipline of financial markets on corporate governance. Specifically, Aggarwal et al. (2011) argue that foreign institutional investors play an important role in promoting good corporate governance across countries. Our paper complements this argument in the sense that we find multinational firms with more foreign institutional ownership have higher ESG ratings.

[Dongxu Li, assistant professor at WangYanan Institute for Studies in Economics (WISE) & School of Economics, Xiamen University; Xiaoxue Hu, M.Phil. student at School of Economics, Xiamen University.]

References

Aggarwal, R., Erel, I., Ferreira, M., & Matos, P. (2011). Does governance travel around the world? Evidence from institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(1), 154-181.

Ben-David, I., Jang, Y., Kleimeier, S., & Viehs, M. (2018). Exporting pollution: Where do multinational firms emit CO2? NBER Working Papers, No. 25063.

Berg, F., Kölbel, J., & Rigobon, R. (2020). Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Working paper.

Chatterji, A. K., Durand, R., Levine, D. I., & Touboul, S. (2016). Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1597-1614.

Edmans, A. (2020). Grow the pie: How great companies deliver both purpose and profit. Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, R., Krueger, P., & Schmidt, P. S. (2020). ESG rating disagreement and stock returns. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper, (19–67).

Li, D. & Hu, X., Does ESG travel around the world? Evidence from multinational firms in an emerging country (October 11, 2021). Working paper.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email