Shadow Banking Activities of Non-Financial Firms in China

The re-lending business is a particular activity of shadow banking in China, in which some non-financial firms borrow in order to lend, acting as de facto financial intermediaries. Julan Du and Chang Li from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Yongqin Wang from Fudan University document this type of shadow banking in China using three different identification strategies. They also explore the factors that influence the firms' re-lending activities.

Our study examines re-lending in corporate China, a particular form of shadow banking activity in emerging markets performed by non-financial firms, in which firms borrow in order to lend. Shadow banking in advanced markets receives great attention. Much less attention has been paid to that in emerging economies like China. There are studies focusing on other dimensions of the Chinese shadow banking system: wealth management products (WMPs) and entrusted loans, which all involve commercial banks (Allen et al., 2015; He et al., 2015; Acharya et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Hachem and Song, 2016). Instead, we focus on non-financial firms’ re-lending business, one of the most opaque components in the shadow banking system.

We try to identify its existence by using three types of strategies to track the abnormal relationships between financial accounts. We also explore factors influencing re-lending and find that firms with better growth opportunities, stronger corporate governance, and more financial constraints engage less in re-lending. State-owned companies are particularly active in re-lending, probably because of their better access to financial markets, lower profitability in their main business, and lack of growth opportunities.What is the re-lending business?

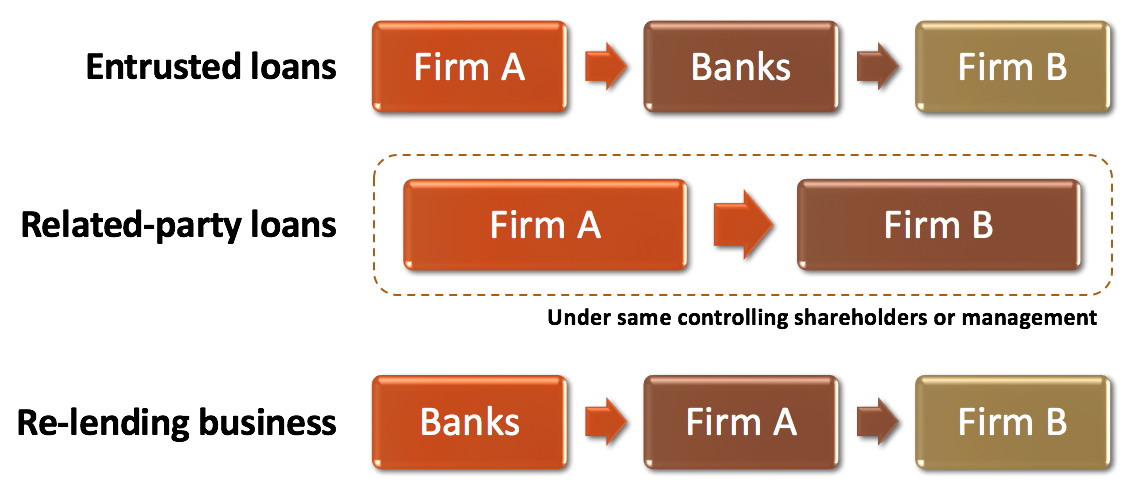

Three forms of lending between two non-financial firms have developed in the Chinese economy:

• Related-party loans

• Entrusted loans

• Re-lending business

Entrusted loans are a type of loan made by non-bank entities (firms, individuals) to another that involves banks as serving agents. The People's Bank of China (PBOC) mandates that a financial institution stands in the middle to ensure the safety of loans, which is the key difference between entrusted loans and re-lending business. Specifically, in re-lending business, some non-financial firms with good access to formal finance act as de facto financial intermediaries, i.e., borrowing from banks or issuing bonds, and then lending to other credit-constrained firms. For example, about one quarter of the profits of Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Holdings came from lending business in 2011. This direct re-lending business and entrusted loans constitute a substantial part of China’s shadow banking system (Financial Times, 2011).

Despite the anecdotal evidence of re-lending by big firms, it is important to empirically identify its existence and causes. There are at least three reasons why re-lending matters. First, it might be an important element of China’s shadow banking system, and uncovering the hidden activity may shed light on how China’s financial system really works. In particular, it would help us understand how China’s financial resources trickledown to other firms outside the traditional banking system. Second, re-lending has implications for China’s macro-prudential policies, given that the re-lending business may reinforce the boom-bust cycles. Third, it may identify a new transmission channel for monetary policy.

There-lending business is hidden because it has been forbidden by law according to General Provisions for Lending enacted in 1996. Although the Chinese judicial system made some concessions by providing a certain degree of de facto recognition of re-lending activities in recent years, at the least, this business was illegal before 2012.

Related-party lending often occurs between firms under common controlling shareholders or management. It is different from re-lending business in terms of interest rates on loans: internal inter-corporate loans always set the interest rate at zero (Jiang et al., 2010), but the interest rates charged in the re-lending market are typically high, reaching 6 or even 8 times as much as the regulated interest rates in the formal credit market. Moreover, related-party loans have been largely cleaned because eight government authorities made joint announcements in 2006 to force firms to solve the issue.

The re-lending business marks a unique feature of shadow banking beyond the finance industry and thus is the focus of our paper. Two distinguishing attributes of the re-lending business should be kept in mind: illegality and high yield. Entrusted loans made up nearly 30% of the increase in social financing in 2013 and have already received much attention from the PBOC, e.g. emphasis in annual stability reports. However, the re-lending business, an important component of private lending, lacks efficient regulation. The scale of private lending was estimated to be about 3.38 trillion yuan in 2013; because of the illegal nature of the re-lending business, we cannot determine its exact extent. But some implications can be drawn from the number of lawsuits and the amount of money involved in legal cases related to private lending: lawsuits jumped from 488,301 in 2008 to more than 1 million in 2014, and the average amount involved in each case increased by nearly 150% from 2008 to 2013.

How do we detect the existence of re-lending business?

As re-lending is an illegal activity for non-financial firms, we make great efforts to detect it by digging into the balance sheets of listed companies. Specifically, we use three strategies to track the abnormal relationships between financial accounts.

• The correlation between liquidity holdings and financial liabilities

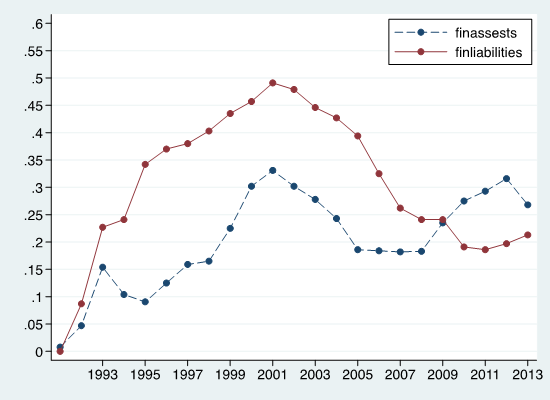

This strategy is based on the pecking order theory (Myers, 1984), which was also applied in Shin and Zhao (2013). In a normal case, firms, in order to finance investments, prefer to use internal funds first and only tap external funds in the case of inadequate liquid holdings. More specifically, when a firm prepares for investments, it begins by decreasing liquid assets, such as cash holdings or bank deposits, and then turns to borrowing from banks or issuing new bonds either because internal funds are inadequate or because the firm plans to keep some liquid assets for daily operations. Thus, we should observe that financial assets and financial liabilities move in opposite directions. Figure 2 provides a smell test. The expectedly negative correlation is verified by the pattern of U.S. firms.

In contrast, if firms serve as financial intermediaries by simultaneously borrowing and lending (borrowing in order to lend in the re-lending business), they may exhibit a pattern similar to commercial banks, resulting in the same direction of movements in liquid financial assets and total debts. This is exactly what we find in our paper: non-financial firms in China exhibit a significantly positive relationship between liquidity holdings and financial liabilities, implying participation in re-lending activities. But there is striking heterogeneity among different firms. State-controlled firms, especially central-government-controlled firms, have substantial shadow banking activities, whereas private or foreign-controlled firms do not. This is consistent with the fact that SOEs are less subject to credit constraints and have a higher availability of funds for re-lending.

• The correlation between liquidity holdings and business fixed investments

It can be argued that the observed positive correlation between financial assets and liabilities is because firms temporarily wait for better investment opportunities, so raised funds are put in the category of liquid financial assets. In that case, we expect to observe that an increase in business fixed investments would be associated with a decrease in cash holdings. Moreover, firms usually carefully match the timing of raising funds and that of investing so as to minimize the opportunity costs of holding idle funds.

In contrast, if firms borrow from banks in order to re-lend, in other words, a considerable amount of liquidity holdings are not used to finance investments, obviously the relationship between liquidity and business fixed investment becomes weak or even reversed. Excess demand for financing under financial repression leads to a seller’s market for loans; re-lending firms have the market power to set interest rates and terms of loans. This advantage further loosens the relationship between business fixed investments and liquid financial assets.

Our paper shows that the correlation between liquid financial assets and business fixed investments is positive for Chinese non-financial firms, lending support to the existence of shadow banking activities. For a better understanding of the implication of this observed pattern, we conduct identical regressions using U.S. firms over the same sample period and find that U.S. firms do not exhibit the abnormal pattern found in Chinese firms.

• Loan outflow and interest inflow on financial statements

Firms tend to hide re-lending business on their balance sheets because of the illegal nature; for example, interest income cannot be recorded in the category of “interest revenue.” According to our interviews with industry experts in China and the investigation of footnotes in financial reports, the re-lent loans on balance sheets of non-financial firms are usually put into the category of “other receivables,” and interest income is usually recorded in the category of “non-operating income” or used to write down “financial expenses.”

Our empirical work partly confirms the oral reports. According to the firm-level data, we find that the amount of debt is highly correlated with other receivables (even adjusted to the U.S. industry median of other receivables), and the positive correlation only holds for state-controlled firms, suggesting that a fraction of borrowed funds flows to re-lending business. Furthermore, an increase in other receivables is associated with an increase in non-operating income but a decrease in financial expenses, revealing that the re-lending business generates considerable profit. By contrast, the correlation between other receivables and financial expenses is insignificant before 2006, during which related-party loans, normally at a zero interest rate, dominated the “other receivables" accounts.

What influences the participation in re-lending business?

• Macro-environment

Lending is related to money, so of course market liquidity is an important factor. In our paper, the monetary policies and social financing data (the amount of bank loans) are quoted to measure market liquidity. The data suggests that the re-lending business is adversely affected by monetary tightening but encouraged by the increase of bank loans in the economy. In particular, state-controlled firms are less hurt by the contractionary monetary policies but ride on the formal credit boom more strikingly.

• Firm characteristics

Why do firms engage in an illegal business? High profits. Thus we are motivated to examine whether the growing opportunities affect engaging in the re-lending business. As expected, evidence shows that firms with higher profitability (lagged ROA), better growth prospects (higher P/E ratio), and stronger business growth (total assets growth) display less re-lending. We further show that strong corporate governance (represented by greater shares held by directors, separation between CEO and board chairman, and a high proportion of outside directors), which is expected to reduce operational risks, indeed curbs the re-lending business.

We then analyze the impact of credit constraints faced by non-financial firms. After all, not only market liquidity but also firm liquidity, are crucial to participation in re-lending. Our results show that a high level of external finance dependence deters firms from engaging in shadow banking and abundant trade credit promotes re-lending. Yet the effects of credit constraints only hold in private firms; they diminish in state-controlled firms. This is consistent with findings in the literature that private-controlled firms are much more subject to credit constraints than state-controlled firms.

Going forward

Overall, our work studies the re-lending business of non-financial firms, an important aspect of shadow banking activities in emerging markets, based on the experience of corporate China. Understanding the mechanisms of the re-lending business would equip government authorities with the necessary surveillance tools and insight into the design of regulatory policies. Therefore, future studies could consider the economic consequences and risks brought about by such financial intermediary activities beyond the financial industry, either empirically or theoretically, e.g. Capital allocation efficiency or the transmission mechanism of monetary policies.

(Julan Du, Department of Economics, Chinese University of Hong Kong; Chang Li, Department of Economics, Chinese University of Hong Kong; Yongqin Wang, School of Economics, Fudan University.)

References

Acharya, V.V., J., Qian, and Z.S., Yang (2016). “In the Shadow of Banks: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks’ risk in China.” Working paper.

Allen, F., Y.M., Qian, G.Q., Tu, and F., Yu (2015). “Entrusted Loans: A Close Look at China’s Shadow Banking System.” Working paper.

Chen, K.J., J., Ren, and T., Zha (2016). “What We Learn from China’s Rising Shadow Banking: Exploring the Nexus of Monetary Tightening and Banks’ Role in Entrusted Lending.” NBER working paper.

Du, J., C., Li, and Y., Wang (2016). “Shadow Banking Activities in Non-Financial Firms: Evidence from China.” Working paper.

Financial Times (2011). “China Groups Fuel Growth of Shadow Banking,” September6. (https://www.ft.com/content/dcd45d08-d888-11e0-8f0a-00144feabdc0).

Hachem, K., and Z.M., Song (2016). “Liquidity Regulation and Unintended Financial Transformation in China,” NBER working paper No. 21880.

He, Q., L., Lu, and S., Ongena (2015). “Who Gains from Credit Granted Between Firms? Evidence from Inter-Corporate Loan Announcements Made in China.” Bank of Finland Discussion Paper.

Jiang, G., C.M., Lee, and H., Yue (2010). “Tunneling through Intercorporate Loans: The China Experience.” Journal of Financial Economics 98 (1), 1-20.

Myers, S.C. (1984). “The Capital Structure Puzzle.” The Journal of Finance 39 (3), 574-592.

Shin, H.S., and L., Zhao (2013). “Firms as Surrogate Intermediaries: Evidence from Emerging Economies.” Working paper.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email