A Biological Clock Explanation for the Gender Gap in Earnings: Import Competition Increases Female Fertility

Rising import competition from emerging countries such as China, which are increasingly integrated in the global economy, have led to lower labor market opportunities in many high-income countries, especially for middle-class manufacturing workers (see Keller and Utar, 2019). This article shows that the implications of rising import competition go beyond the labor market and also affect family size and structure.

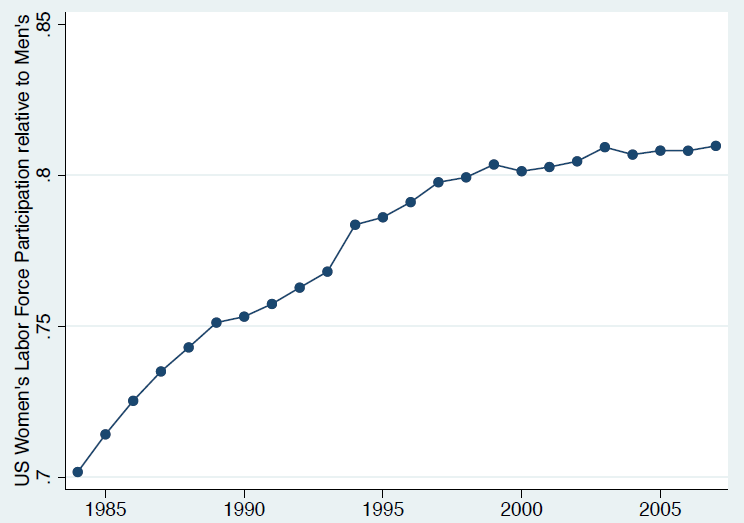

For many countries, the 20th century will reflect a history of equalization of women’s and men’s opportunities in the labor market. With regards to labor force participation in the U.S., for example, shortly after World War II, men were almost three times as likely to be in the labor force as women, whereas by the year 2008 women’s labor force participation stood at about 83 percent of men’s, as Figure 1 (top) shows.

Figure 1: Women’s Labor Force Participation; Age of First-Time Motherhood

In striking contrast to the strong trend for much of the 20th century, there has hardly been any convergence in the labor force participation rates across gender since the early 2000s. While there might be a number of factors (see Fortin, 2005; Goldin, 2014), this column argues that one should consider changing labor market opportunities along with family outcomes that determine the work-life balance of men and women. In particular, the lower panel of Figure 1 shows that, sometime in the early 2000s, both U.S. and Danish women began to cease the postponement of motherhood, which typically occurs as human capital investments enhance labor market opportunities.

Recent evidence shows that differences in the labor adjustment of men and women to globalization plays an important role in this. When faced with a negative labor market shock of a given size, female workers are more likely than male workers to take a leave out of the labor market for family goals, especially children—presumably because women can give birth but men cannot and, in contrast to men, women are rarely able to achieve their goals for fertility beyond a certain age.

In Keller and Utar (2020), we study the effects on Danish workers of rising exports from China as the country entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in late 2001. This intensified import competition from China has closed many career paths in the manufacturing sector in Denmark, and has left a switch to the growing service sector as the only viable path. The study investigates how this loss of labor market opportunities for workers due to a plausibly exogenous shock affects fertility, childcare uptake, and the formation and duration of marital unions. Crucially, rising import competition is but one type of labor demand shock that may trigger gender differentials, because women respond by establishing a different work-life balance than men due to their specific biological clock; another type of labor demand shock is job displacement due to plant closure, for example (see Del Bono, Weber, and Winter-Ebmer, 2012; Huttunen and Kellokumpu, 2016).

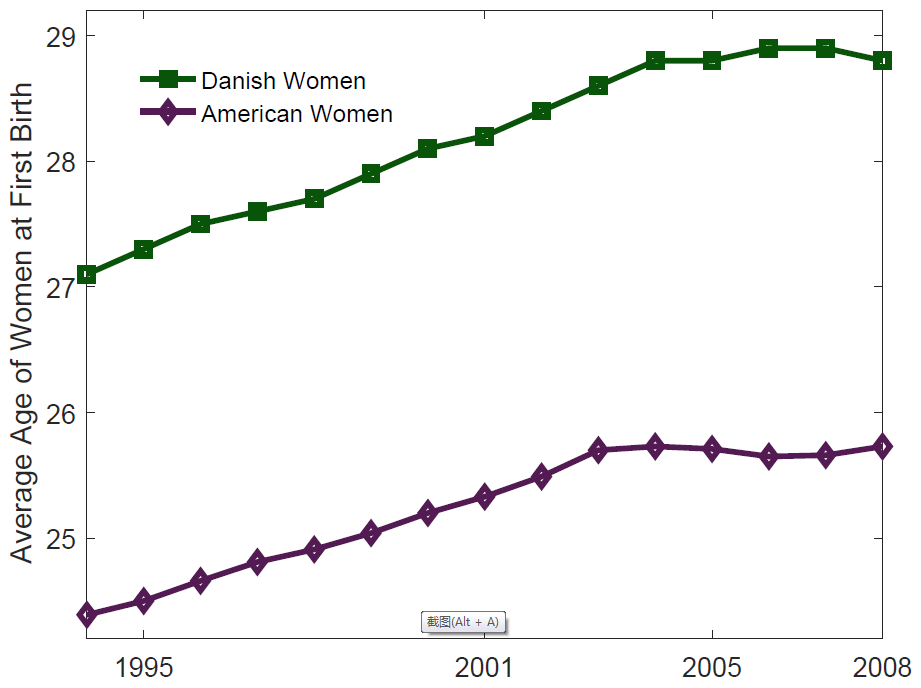

We have combined administrative data on all firms and their workers with complete family histories from population registers. This allows us to follow workers from job to job (or unemployment) as they make key family decisions on co-habitation, marriage, divorce, and children. The impact of the negative labor shock is found by comparing labor market and family experiences of workers employed at Danish firms that are hit hard by rising import competition from China with the experiences of workers who are much less affected. Figure 2 shows the impact on labor earnings between 2002 to 2007 for four sets of workers, women and men who are either young or old (fertile-age and post-fertile-age, respectively).

Figure 2: The Missing Earnings of Fertile-Age Women

First, labor earnings of affected older men are much lower by 2007 than earnings of unaffected older men, in line with a negative impact of import competition on earnings. For younger men, we do not find a comparable impact, because affected young men are able to adjust to the shock by switching to other jobs in other sectors without any delay. Human capital theory tells us that young workers are more willing than older workers to pay the cost of adjustment because they have a longer career ahead of them to recoup the investments.

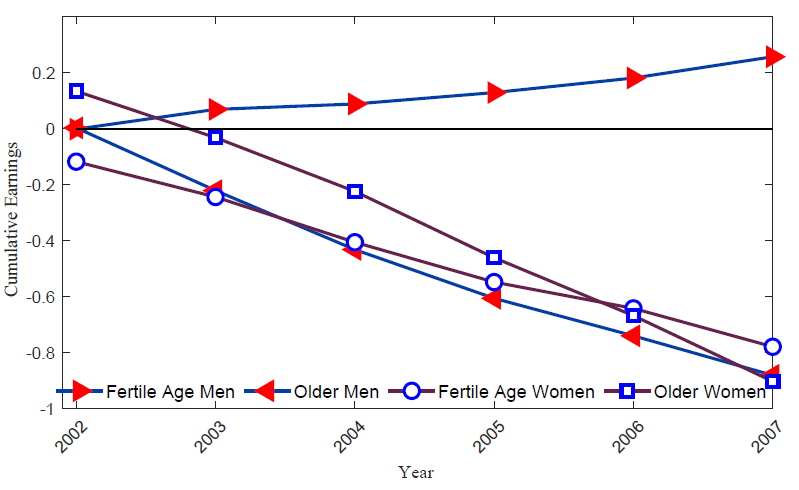

It is striking that the impact of the negative labor shock is very similar for fertile age and older women: both sets lose about 80 percent of their initial annual earnings over the course of five years following the shock. As a result, we show that import competition leads to substantial gender earnings gap, but only among fertile age workers (Figure 3). That is to say, the advantage of being young disappears for women when adjusting to globalization. The question remains: What explains the fact that fertile age women adjust as poorly to the labor market shock as older women do?

One possibility is that women were hit harder than men by import competition from China because women tend to be employed in particularly vulnerable firms, industries, or occupations. Another possibility is that young women have lower earnings than young men because they are more negatively affected by technology shocks that are correlated with import competition. However, our analysis rules out these hypotheses.

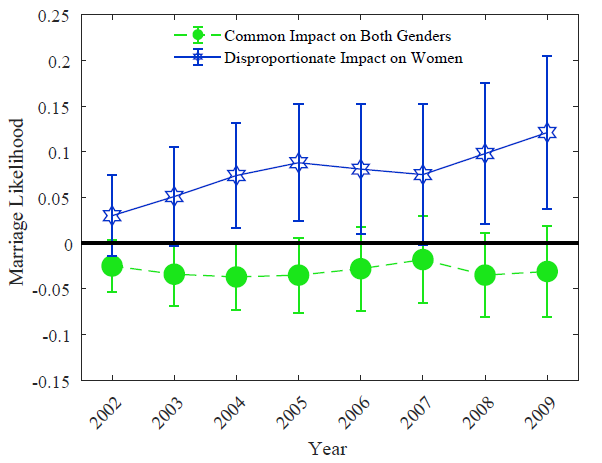

Rather, fertile age women who experience diminished labor market opportunities because of the import competition from China turn towards family life, while men focus more on finding a new career path in the labor market. Figure 4 shows that import competition from China raises the likelihood of marriage for women, while the same is not true for men.

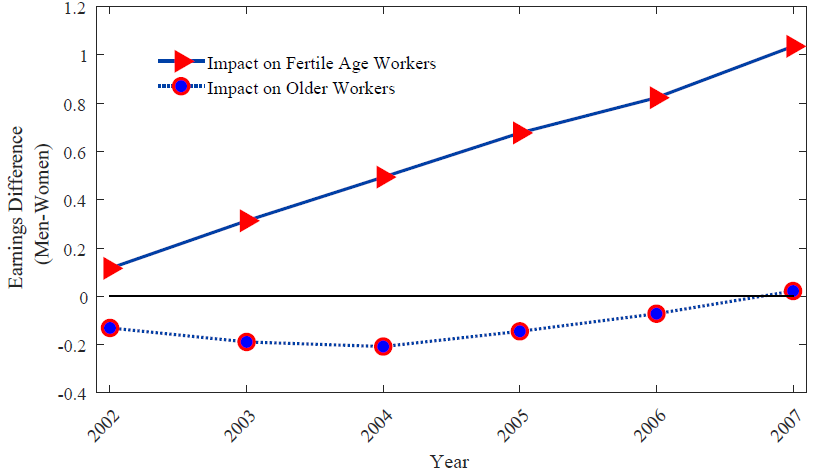

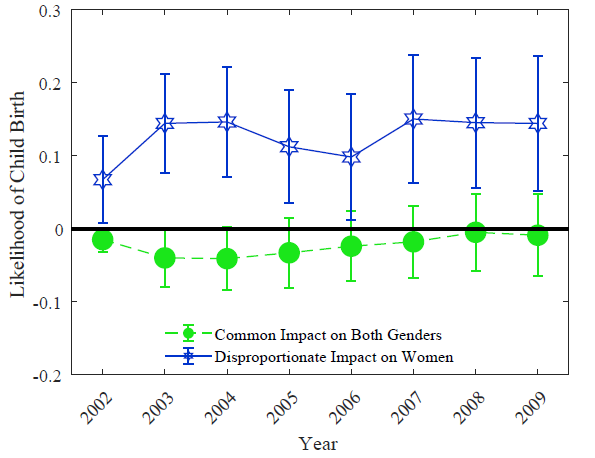

Figure 5 shows that women respond to rising import competition by having more children. The same is not true for men, however. Women in Denmark can respond to a negative labor demand shock by having more children, in part because the country has substantial insurance and transfer policies ensuring that losses in personal income are limited despite the decline in earnings.

Figure 5: Impact of Exposure to Rising Import Competition on Child Birth

In Keller and Utar (2020), we developed the findings in the figures using a rigorous difference-in-difference framework. We also document that, as long as female workers are of fertile age, the tendency to move to family life increases with age, which supports the idea that this choice is motivated by their biological clock.

The move towards family activities mostly happens when women are in a weak labor market position due to import competition, such as unemployment or a period outside the labor market. This supports the view that lower labor market opportunities induce the shift of women from the labor market to family activities.

In sum, our analysis highlights substantial differences in trade adjustment of workers across genders and proposes fertility-related biological differences, and the biological clock in particular, as a new factor behind the non-convergence in labor market performance indicators across gender.

(Wolfgang Keller is Director of the McGuire Center for International Economics and Professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder; Hâle Utar is an Associate Professor and Sidney Meyer Endowed Chair in International Economics at Grinnell College.)

References

Del Bono, Emilia, Andrea Weber, and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer (2012). “Clash of Career and Family: Fertility Decisions after Job Displacement.” Journal of European Economic Association 10(4): 659–683.

Fortin, Nicole (2005). “Gender Role Attitudes and Women’s Labour Market Outcomes.” Mimeo, UBC.

Goldin, Claudia (2014). “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter.” American Economic Review 104(4): 1091–1119.

Huttunen, Kristiina, and Jenni Kellokumpu (2016). "The Effect of Job Displacement on Couples’ Fertility Decisions.” Journal of Labor Economics 34(2): 403–442.

Keller, Wolfgang, and Hâle Utar (2019). “International Trade and Job Polarization: Evidence at the Worker Level.” NBER Working Paper #22315.

Keller, Wolfgang, and Hâle Utar (2020). “Globalization, Gender, and the Family.” NBER Working Paper #25247.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email