Do CEOs Know Best? Evidence from China

Using data from the China Employer-Employee Survey (CEES), a recent survey of Chinese manufacturing firms, we analyze the extent to which employees of differing levels are able to assess their firms’ management practices. Our study finds that of CEOs, managers, and workers, CEOs tend to have the most accurate appraisals of their firms. Additionally, we find that firms with higher levels of disagreement among employees of different levels in their assessments of management practices tend to invest less in R&D and physical capital, potentially indicating such firms focus less on the long run. Thus, our study also highlights the importance of eliciting management evaluations from all employees across a given firm, rather than just the CEO or senior management.

Recently, there has been a surge of interest within economics in management (Roberts, 2018), which has built on a long history of work in the field (e.g. Walker,1887). This work has been heavily based on management surveys covering tens of thousands of firms across dozens of countries. However, one limitation of much of the work on management to date is the primary focus on survey feedback from senior managers. It is well known in the sociological literature that there is often a wide spread of opinions between workers and CEOs within the same firm, to the extent that workers’ evaluations of their firms’ management may provide a valuable counterpart to those of their managers (Ukko et al., 2007). Moreover, the question emerges as to whether managerial disagreement is an important factor in shaping firm performance. Simultaneously, modern management practices focus heavily on standardization, which suggests alignment of management evaluations across the firm should be associated with superior performance. On the other hand, more disagreement may highlight greater independence of workers’ views, which is potentially associated with better firm performance.

The China Employer-Employee Survey

The challenge of addressing these questions has always been obtaining survey responses from representative samples of workers. Approaching firms and asking for a random sample of workers is an unrealistic approach to eliciting random workers’ responses, as managers are unlikely to select workers in a truly random fashion and instead will refer workers who are likely to hold favorable views of the firm. In order to overcome these obstacles, our study exploits a unique survey of Chinese workers, the China Employer-Employee Survey (CEES), which includes data from around 10 respondents per firm. Specifically, it samples the CEO, a set of up to three randomly selected senior managers, and up to seven randomly selected workers. The survey was conducted by a consortium of institutions including Wuhan University, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology in China, and Stanford University in the United States. The survey is overseen and managed by the Quality Control Institute at Wuhan University.

With the support of the Institute’s alumni, the survey team of 300 enumerators visited firms in person to interview employees, achieving a notably high response rate of 86%. By obtaining the employment registry at each firm prior to collecting data, the team members could ensure randomness by personally selecting employees to interview. Hence, this survey is the first management survey to collect information from three groups—the CEO, a truly randomly sampled set of senior managers, and workers. Thus, the CEES survey is exceptional in terms of both coverage and quality.

Before the CEES survey, the lack of high-quality, in-depth data on firms and workers in China prevented systematic study of important issues facing China’s manufacturers. Existing firm datasets contained limited information or lacked a representative sample of firms and workers. The CEES project provides a new data source that can overcome these limitations. The goals of the CEES project include conducting the world’s most comprehensive employer-employee survey of China, longitudinally tracking changes in the situation of both employers and employees, and forming a high-quality dataset that can provide a platform for evidence-based studies of the Chinese economy by economists and policy-makers worldwide.

Analysis of Management Scores

In our study on management in China, we draw on a subsample of CEES data from 2016 that included management scores rating monitoring, targets, and incentives. On average, a firm in this sample had 959 workers and was about 12 years old. About half (48%) of the firms were exporters, and 14% were state-owned enterprises. Out of the 906 firms, 6,692 managers and workers reported management scores. These employees were 36 years old on average and had a high school education.

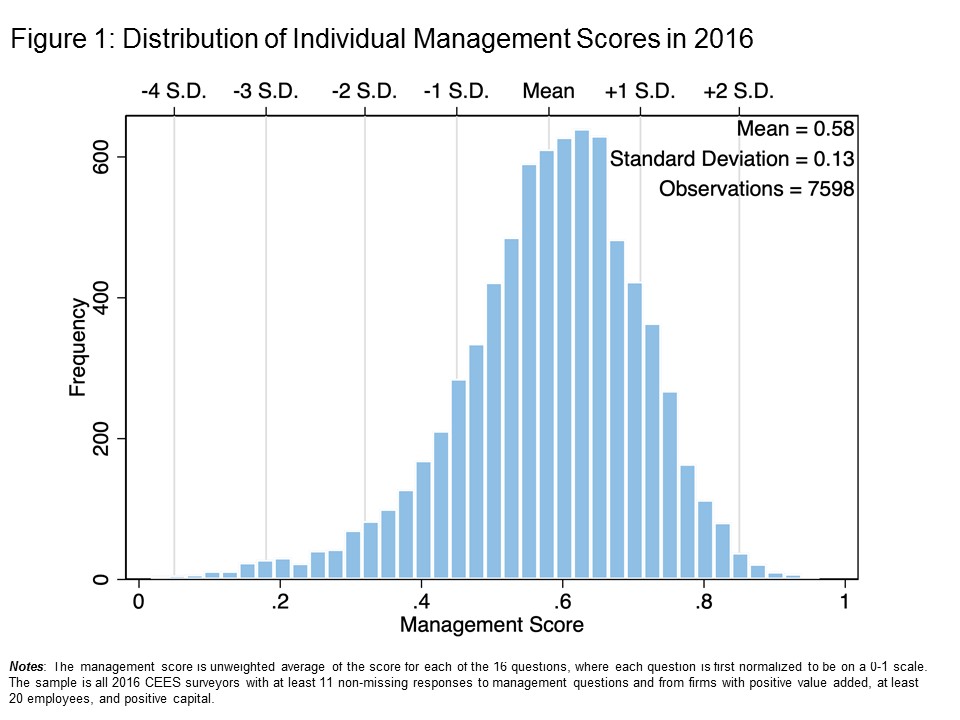

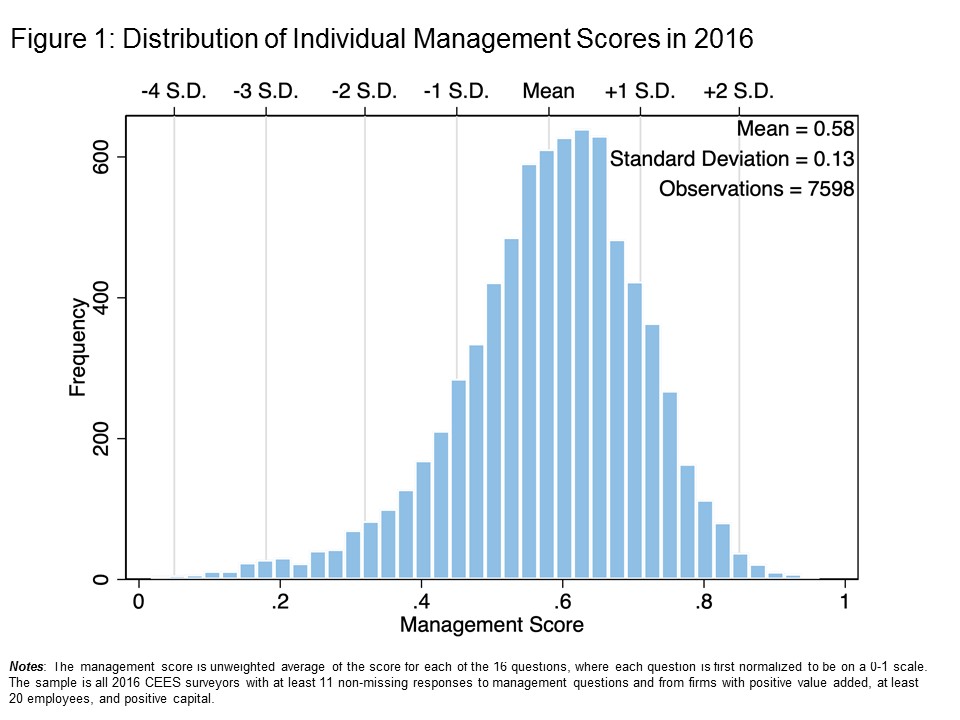

The management scores obtained from the CEES are generally comparable to those from the United States or other surveys in China. We start by pooling all interviews from all employees and showing the distribution of management scores across the firms in China in Figure 1. We see a familiar wide distribution with a long-left tail, much like productivity distributions for China (e.g. Hsieh and Klenow, 2009) or management and productivity distributions for the UnitedStates (e.g. Syverson, 2004; Bloom et al., 2018). When we compare the results for China to previously obtained U.S. management scores, we see that Chinese scores evaluated on a similar basis are significantly lower but have a similar (possibly slightly compressed) spread. Indeed, this also aligns with the results from Bloom, Sadun, and Van Reenen (2017) in the World Management Survey, which, using a different telephone survey management scoring tool, also finds a higher and more dispersed score in the United States than in China.

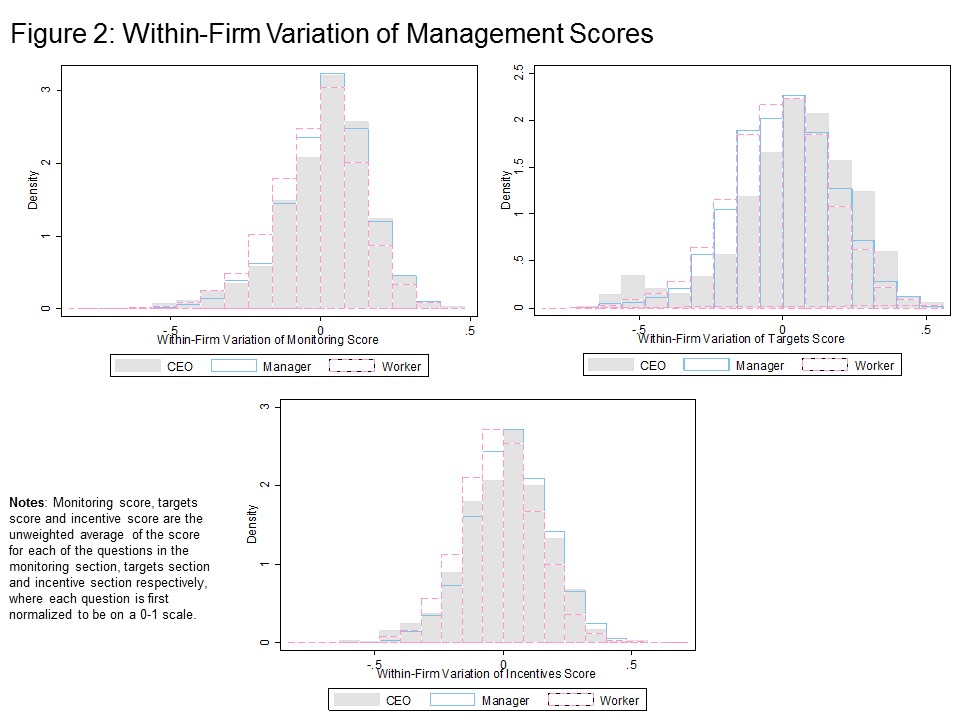

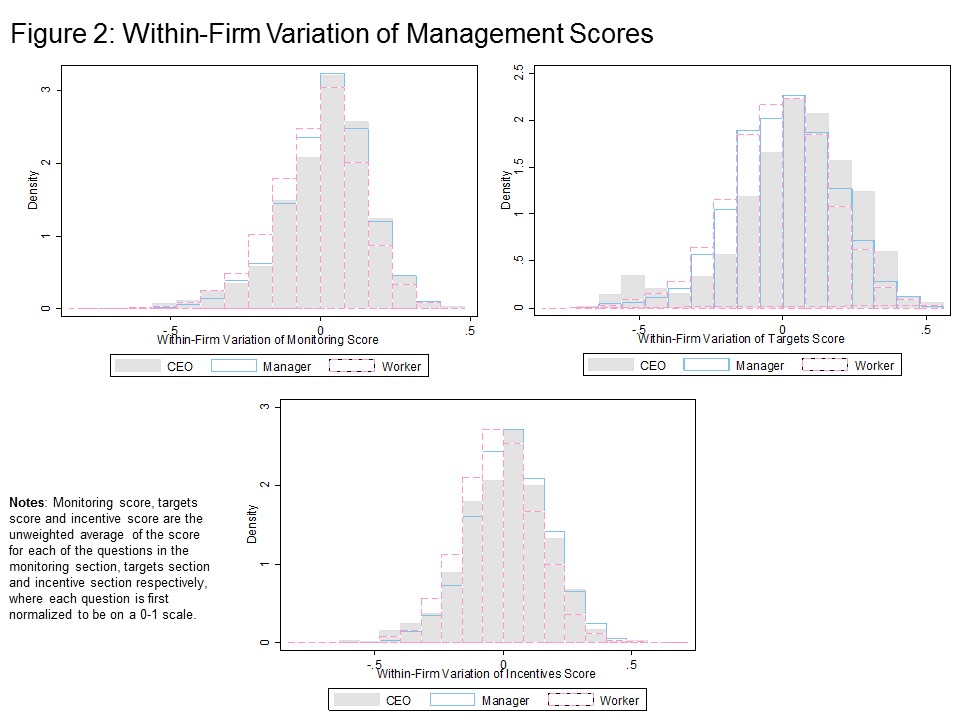

Moreover, the distributions of scores for different types of workers and for different management practices are similar. In Figure 2, we plot the scores across the three main groups of management practices—monitoring, targets, and incentives—and for the CEOs, workers, and managers, respectively (See Note 1). These three groups clearly have incredibly similar distributions. There is some variation—in particular, workers have slightly lower scores on monitoring and targets, while managers appear to have higher scores on incentives—but broadly speaking, these line up closely (at least much more closely than any of the co-authors anticipated). Finally, our analysis of initial survey results reveals a strong correlation between CEO management scores and those of managers and lower-level workers.

Regression analyses of our results show that management scores of all three types of employees are highly correlated with firm performance, and that CEO scores in particular seem to be most informative about performance. More specifically, in our regressions, we examined multiple performance measures, including value-added per employee, employment growth, and profit/sales, and the scores reported by the CEOs were consistently the most closely correlated with these values. In light of this result, we also considered whether the average of the scores from other managers or lower-level workers might be more informative overall than those of the CEO. That is, while the CEO might provide the singularly most informative management score, groups of managers or workers could potentially be more informative—in a “wisdom of crowds” sense. Nevertheless, we find that this is usually not the case. Therefore, we conclude from our results that CEO management scores do indeed seem to be the best predictors of firm performance outcomes. In that sense, CEOs do seem to “know best” about the management practices in their firm that are most predictive of firm performance.

Given our range of scores within the firm, another natural question arises: is disagreement over management scores correlated with better or worse firm performance? On the one hand, disagreement might be a sign of a badly run firm, suggesting weak internal information sharing or employee disengagement. On the other hand, more disagreement may also highlight greater independence of employee views, which could potentially be associated with improved firm performance. After an empirical investigation, which involved analyzing the deviation of each employee’s overall score from the firm mean, we concluded that disagreement among employees about management practices does not seem to have a strong correlation with firm performance overall, but does seem to suggest lower long-run investment in tangible and intangible capital. Nonetheless, disagreement does seem to reduce the positive correlation between performance and management. The management-performance relationship is significantly weaker in firms with more management disagreement, suggesting that greater disagreement indicates a weaker signal value of management to performance. This may be because the firms’ management practices are harder to evaluate or possibly because disagreement indicates a higher level of management error in the survey responses from the firm.

Conclusions

To summarize, our analysis of management scores using the CEES data yields four main results. First, management scores, much like productivity, have a wide spread with a long left-tail of poorly managed firms. This distribution of management scores is similar for CEOs, senior managers, and lower-level workers, and it appears reasonable overall compared to U.S. scores for similar questions. Moreover, for all groups, these scores correlate with firm performance, suggesting all employees within the firm are (at least partly) aware of the firms’ managerial abilities. Second, the scores across the groups are significantly cross-correlated, but far from completely. This suggests that while different levels of the firm have similar views on the firms’ management capabilities, they do not fully agree. Third, we find that the management scores from CEOs are the most predictive of firm performance, followed by the senior managers and then the workers. Hence, CEOs do appear to know best about their firms’ management strengths and weaknesses. Finally, disagreement between employees over management practices is negatively correlated with investment in R&D and physical capital, potentially indicating a less long-run focus among firms. Indeed, this study highlights the importance of eliciting management evaluations from all employees across a given firm, rather than just the CEO or senior management.

Note 1: The management module in the CEES survey contained 16 questions, which were separated into three sections: monitoring, targets, and incentives. The monitoring section asked firms about their collection and use of information to monitor and improve the production process. The targets section asked about the design, integration, and realism of production targets. Finally, the incentives section asked about non-managerial and managerial bonuses, production, and reassignment/dismissal practices.

Bandiera, Oriana Renata Lemos, Andrea Prat and Raffaella Sadun, (2017). “Managing the Family Firm: Evidence from CEOs at Work,” Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2363528

Bertrand, Marianne and Antoinette Schoar, (2003). “Managing with Style: The Effect of Managers on Firm Policies,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (4), 1169–1208.

http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/marianne.bertrand/research/papers/managing_style_qje.pdf

Bloom, Nicholas and John Van Reenen, (2007). “Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across Firms and Countries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w12216

Bloom, Nicholas, Erik Brynjolfsson, Lucia Foster, Ron Jarmin, Megha Patnaik, Megha, Itay Saporta-Ekstein and John Van Reenen, (2018). “What Drives Differences in Management?” Stanford mimeo.

https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/drivers_round2_2018.pdf

Bloom, Nicholas, Raffaella Sadun and John Van Reenen, (2017). “Management as a Technology,” NBER Working Paper No. 22327.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w22327

Bloom, Nicholas, Steve Davis, Lucia Foster, Brian Lucking, Scott Ohlmacher and Itay Saporta Eckstein, (2017). “Business-Level Expectations and Uncertainty,” Stanford mimeo.

https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/bleu_ssrn.pdf

Enterprise Surveys, (2018). The World Bank, http://www.enterprisesurveys.org.

Gennaioli, Nicola, Yueran Ma, and Andrei Shleifer, (2016). “Expectations and Investment.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30, no. 1.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w21260

Gibbons, Robert and John Roberts, (2013). The Handbook of Organizational Economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Halac, Marina and Andrea Prat, (2016). “Managerial Attention and Worker Engagement,” American Economic Review, 106(10): 3104–3132.

https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=10035

Kiechel, Walter, (2012). “The Management Century,” Harvard Business Review, November.

https://hbr.org/2012/11/the-management-century

Lazear, Edward, Shaw, Kathryn and Stanton, Christopher, (2016), “The Value of Bosses,” Journal of Labor Economics.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w18317

Roberts, John, (2018), “Needed: Economic Analyses of Management,” International Journal of Economics of Business, forthcoming.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13571516.2017.1403199

Syverson, Chad, (2004). “Market Structure and Productivity: A Concrete Example.” Journal of Political Economy, 112(6), 1181-1222.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/424743

Syverson, Chad, (2011). “What Determines Productivity?” Journal of Economic Literature, 49(2), 326-365.

http://home.uchicago.edu/syverson/productivitysurvey.pdf

Ukko, Juhani, J. Tenhunen and H. Rantanen, (2007). “Performance Measurement Impacts on Management and Leadership: Perspectives of Management and Employees.” International Journal of Production Economics, 110(1-2), 39-51.

http://www.stou.ac.th/Schools/Shs/upload/J%2011_%20Performance%20measurement%20impacts%20on%20Management%20and%20leadership_%20Int%20J%20Production%20Economics%20110%202007.pdf

Walker, Francis, (1887). “On the Sources of Business Profits,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1 (3), 265-288.

Recently, there has been a surge of interest within economics in management (Roberts, 2018), which has built on a long history of work in the field (e.g. Walker,1887). This work has been heavily based on management surveys covering tens of thousands of firms across dozens of countries. However, one limitation of much of the work on management to date is the primary focus on survey feedback from senior managers. It is well known in the sociological literature that there is often a wide spread of opinions between workers and CEOs within the same firm, to the extent that workers’ evaluations of their firms’ management may provide a valuable counterpart to those of their managers (Ukko et al., 2007). Moreover, the question emerges as to whether managerial disagreement is an important factor in shaping firm performance. Simultaneously, modern management practices focus heavily on standardization, which suggests alignment of management evaluations across the firm should be associated with superior performance. On the other hand, more disagreement may highlight greater independence of workers’ views, which is potentially associated with better firm performance.

The China Employer-Employee Survey

The challenge of addressing these questions has always been obtaining survey responses from representative samples of workers. Approaching firms and asking for a random sample of workers is an unrealistic approach to eliciting random workers’ responses, as managers are unlikely to select workers in a truly random fashion and instead will refer workers who are likely to hold favorable views of the firm. In order to overcome these obstacles, our study exploits a unique survey of Chinese workers, the China Employer-Employee Survey (CEES), which includes data from around 10 respondents per firm. Specifically, it samples the CEO, a set of up to three randomly selected senior managers, and up to seven randomly selected workers. The survey was conducted by a consortium of institutions including Wuhan University, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology in China, and Stanford University in the United States. The survey is overseen and managed by the Quality Control Institute at Wuhan University.

With the support of the Institute’s alumni, the survey team of 300 enumerators visited firms in person to interview employees, achieving a notably high response rate of 86%. By obtaining the employment registry at each firm prior to collecting data, the team members could ensure randomness by personally selecting employees to interview. Hence, this survey is the first management survey to collect information from three groups—the CEO, a truly randomly sampled set of senior managers, and workers. Thus, the CEES survey is exceptional in terms of both coverage and quality.

Before the CEES survey, the lack of high-quality, in-depth data on firms and workers in China prevented systematic study of important issues facing China’s manufacturers. Existing firm datasets contained limited information or lacked a representative sample of firms and workers. The CEES project provides a new data source that can overcome these limitations. The goals of the CEES project include conducting the world’s most comprehensive employer-employee survey of China, longitudinally tracking changes in the situation of both employers and employees, and forming a high-quality dataset that can provide a platform for evidence-based studies of the Chinese economy by economists and policy-makers worldwide.

Analysis of Management Scores

In our study on management in China, we draw on a subsample of CEES data from 2016 that included management scores rating monitoring, targets, and incentives. On average, a firm in this sample had 959 workers and was about 12 years old. About half (48%) of the firms were exporters, and 14% were state-owned enterprises. Out of the 906 firms, 6,692 managers and workers reported management scores. These employees were 36 years old on average and had a high school education.

The management scores obtained from the CEES are generally comparable to those from the United States or other surveys in China. We start by pooling all interviews from all employees and showing the distribution of management scores across the firms in China in Figure 1. We see a familiar wide distribution with a long-left tail, much like productivity distributions for China (e.g. Hsieh and Klenow, 2009) or management and productivity distributions for the UnitedStates (e.g. Syverson, 2004; Bloom et al., 2018). When we compare the results for China to previously obtained U.S. management scores, we see that Chinese scores evaluated on a similar basis are significantly lower but have a similar (possibly slightly compressed) spread. Indeed, this also aligns with the results from Bloom, Sadun, and Van Reenen (2017) in the World Management Survey, which, using a different telephone survey management scoring tool, also finds a higher and more dispersed score in the United States than in China.

Moreover, the distributions of scores for different types of workers and for different management practices are similar. In Figure 2, we plot the scores across the three main groups of management practices—monitoring, targets, and incentives—and for the CEOs, workers, and managers, respectively (See Note 1). These three groups clearly have incredibly similar distributions. There is some variation—in particular, workers have slightly lower scores on monitoring and targets, while managers appear to have higher scores on incentives—but broadly speaking, these line up closely (at least much more closely than any of the co-authors anticipated). Finally, our analysis of initial survey results reveals a strong correlation between CEO management scores and those of managers and lower-level workers.

Regression analyses of our results show that management scores of all three types of employees are highly correlated with firm performance, and that CEO scores in particular seem to be most informative about performance. More specifically, in our regressions, we examined multiple performance measures, including value-added per employee, employment growth, and profit/sales, and the scores reported by the CEOs were consistently the most closely correlated with these values. In light of this result, we also considered whether the average of the scores from other managers or lower-level workers might be more informative overall than those of the CEO. That is, while the CEO might provide the singularly most informative management score, groups of managers or workers could potentially be more informative—in a “wisdom of crowds” sense. Nevertheless, we find that this is usually not the case. Therefore, we conclude from our results that CEO management scores do indeed seem to be the best predictors of firm performance outcomes. In that sense, CEOs do seem to “know best” about the management practices in their firm that are most predictive of firm performance.

Given our range of scores within the firm, another natural question arises: is disagreement over management scores correlated with better or worse firm performance? On the one hand, disagreement might be a sign of a badly run firm, suggesting weak internal information sharing or employee disengagement. On the other hand, more disagreement may also highlight greater independence of employee views, which could potentially be associated with improved firm performance. After an empirical investigation, which involved analyzing the deviation of each employee’s overall score from the firm mean, we concluded that disagreement among employees about management practices does not seem to have a strong correlation with firm performance overall, but does seem to suggest lower long-run investment in tangible and intangible capital. Nonetheless, disagreement does seem to reduce the positive correlation between performance and management. The management-performance relationship is significantly weaker in firms with more management disagreement, suggesting that greater disagreement indicates a weaker signal value of management to performance. This may be because the firms’ management practices are harder to evaluate or possibly because disagreement indicates a higher level of management error in the survey responses from the firm.

Conclusions

To summarize, our analysis of management scores using the CEES data yields four main results. First, management scores, much like productivity, have a wide spread with a long left-tail of poorly managed firms. This distribution of management scores is similar for CEOs, senior managers, and lower-level workers, and it appears reasonable overall compared to U.S. scores for similar questions. Moreover, for all groups, these scores correlate with firm performance, suggesting all employees within the firm are (at least partly) aware of the firms’ managerial abilities. Second, the scores across the groups are significantly cross-correlated, but far from completely. This suggests that while different levels of the firm have similar views on the firms’ management capabilities, they do not fully agree. Third, we find that the management scores from CEOs are the most predictive of firm performance, followed by the senior managers and then the workers. Hence, CEOs do appear to know best about their firms’ management strengths and weaknesses. Finally, disagreement between employees over management practices is negatively correlated with investment in R&D and physical capital, potentially indicating a less long-run focus among firms. Indeed, this study highlights the importance of eliciting management evaluations from all employees across a given firm, rather than just the CEO or senior management.

Note 1: The management module in the CEES survey contained 16 questions, which were separated into three sections: monitoring, targets, and incentives. The monitoring section asked firms about their collection and use of information to monitor and improve the production process. The targets section asked about the design, integration, and realism of production targets. Finally, the incentives section asked about non-managerial and managerial bonuses, production, and reassignment/dismissal practices.

(Nicholas Bloom, Stanford University; Hong Cheng, Wuhan University, Mark Duggan, Stanford University; Hongbin Li, Stanford University; Franklin Qian, Stanford University.)

Bandiera, Oriana Renata Lemos, Andrea Prat and Raffaella Sadun, (2017). “Managing the Family Firm: Evidence from CEOs at Work,” Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2363528

Bertrand, Marianne and Antoinette Schoar, (2003). “Managing with Style: The Effect of Managers on Firm Policies,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (4), 1169–1208.

http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/marianne.bertrand/research/papers/managing_style_qje.pdf

Bloom, Nicholas and John Van Reenen, (2007). “Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across Firms and Countries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w12216

Bloom, Nicholas, Erik Brynjolfsson, Lucia Foster, Ron Jarmin, Megha Patnaik, Megha, Itay Saporta-Ekstein and John Van Reenen, (2018). “What Drives Differences in Management?” Stanford mimeo.

https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/drivers_round2_2018.pdf

Bloom, Nicholas, Raffaella Sadun and John Van Reenen, (2017). “Management as a Technology,” NBER Working Paper No. 22327.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w22327

Bloom, Nicholas, Steve Davis, Lucia Foster, Brian Lucking, Scott Ohlmacher and Itay Saporta Eckstein, (2017). “Business-Level Expectations and Uncertainty,” Stanford mimeo.

https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/bleu_ssrn.pdf

Enterprise Surveys, (2018). The World Bank, http://www.enterprisesurveys.org.

Gennaioli, Nicola, Yueran Ma, and Andrei Shleifer, (2016). “Expectations and Investment.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30, no. 1.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w21260

Gibbons, Robert and John Roberts, (2013). The Handbook of Organizational Economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Halac, Marina and Andrea Prat, (2016). “Managerial Attention and Worker Engagement,” American Economic Review, 106(10): 3104–3132.

https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=10035

Kiechel, Walter, (2012). “The Management Century,” Harvard Business Review, November.

https://hbr.org/2012/11/the-management-century

Lazear, Edward, Shaw, Kathryn and Stanton, Christopher, (2016), “The Value of Bosses,” Journal of Labor Economics.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w18317

Roberts, John, (2018), “Needed: Economic Analyses of Management,” International Journal of Economics of Business, forthcoming.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13571516.2017.1403199

Syverson, Chad, (2004). “Market Structure and Productivity: A Concrete Example.” Journal of Political Economy, 112(6), 1181-1222.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/424743

Syverson, Chad, (2011). “What Determines Productivity?” Journal of Economic Literature, 49(2), 326-365.

http://home.uchicago.edu/syverson/productivitysurvey.pdf

Ukko, Juhani, J. Tenhunen and H. Rantanen, (2007). “Performance Measurement Impacts on Management and Leadership: Perspectives of Management and Employees.” International Journal of Production Economics, 110(1-2), 39-51.

http://www.stou.ac.th/Schools/Shs/upload/J%2011_%20Performance%20measurement%20impacts%20on%20Management%20and%20leadership_%20Int%20J%20Production%20Economics%20110%202007.pdf

Walker, Francis, (1887). “On the Sources of Business Profits,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1 (3), 265-288.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1882759.pdf

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email