Selective Default by Local Governments in China

We identify bank loans to China’s local government financing vehicles and find that 1.7% of the loans that matured during the sample period failed to make the due payments. The LGFV loan default rate is much higher for commercial banks than for the China Development Bank, which provides more comprehensive financing for local governments than typical commercial banks. This selective default pattern is weaker during the ¥4-trillion stimulus period but stronger after 2010 when commercial banks exited the LGFV market.

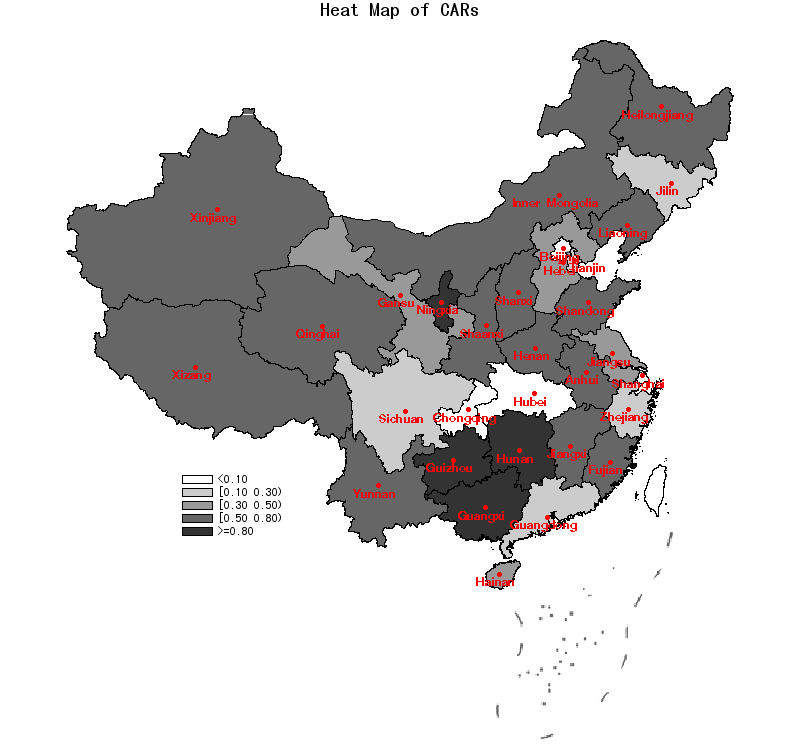

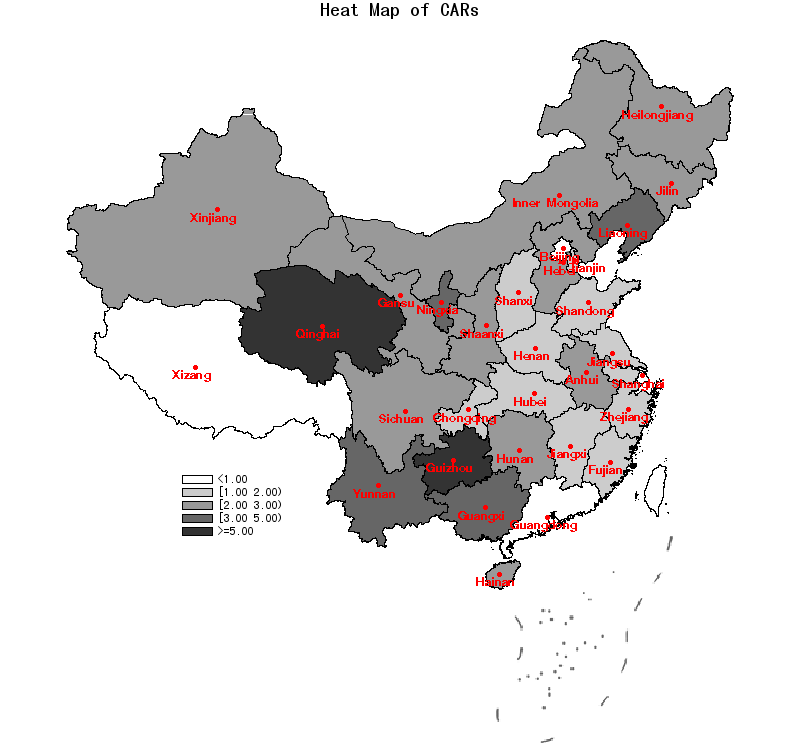

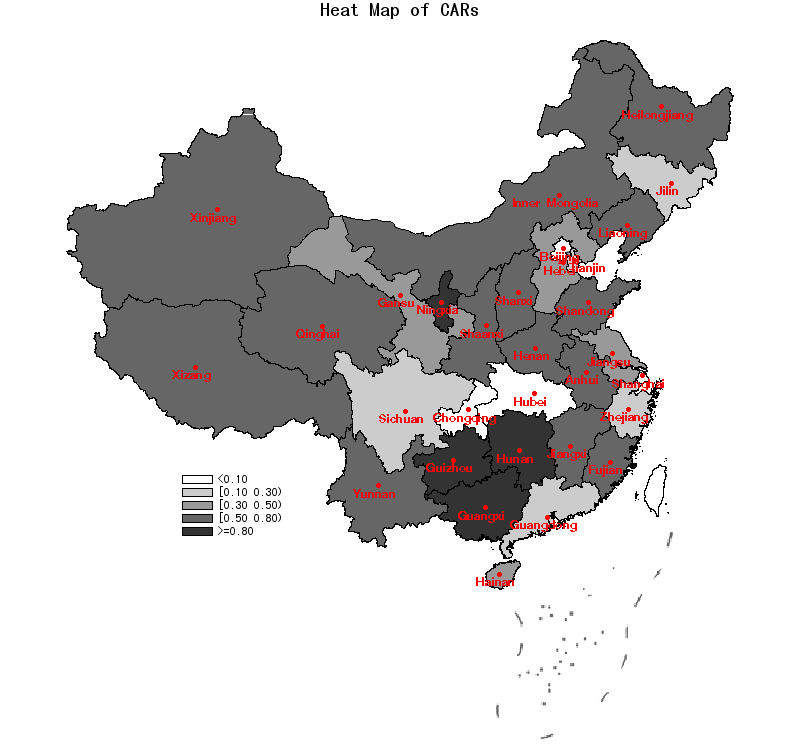

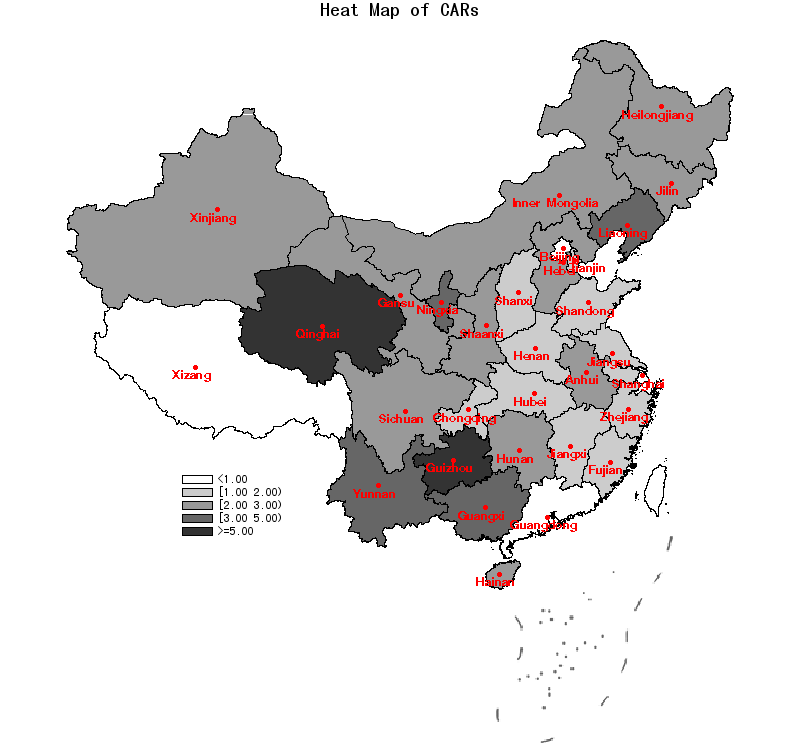

China’s economy has been growing rapidly for the past four decades. It is currently the second largest economy worldwide and contributes approximately 30% of global GDP growth annually. However, this remarkable growth has been fueled by debt financing in recent years, especially local government debt, which—according to official data—increased from ¥1.5 trillion in 2002 to ¥15.3 trillion in 2016. We plot the growth rate of provincial government debt (counting only the explicit debt for which the government is liable) from June 2013 to December 2016 in Figure 1. Guizhou province experienced the fastest growth (88.4%) during this period (from ¥462.3 billion to ¥871.0 billion). The indebtedness of local governments in China in terms of the debt-to-fiscal revenue ratio for each province in China at the end of 2016 is illustrated in Figure 2. The most indebted provinces have ratios above five. The IMF has recently warned China about dangerous debt growth. In 2017, both Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s downgraded the sovereign credit rating of China, and Fitch made a prediction about the first default of bonds issued by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs).

Notes: This figure illustrates the growth rate of

the total amount of outstanding debt that provincial governments are

directly liable to repay.

This figure illustrates the outstanding

debt amount to local fiscal revenue ratios for all provinces in China at

the end of 2016.

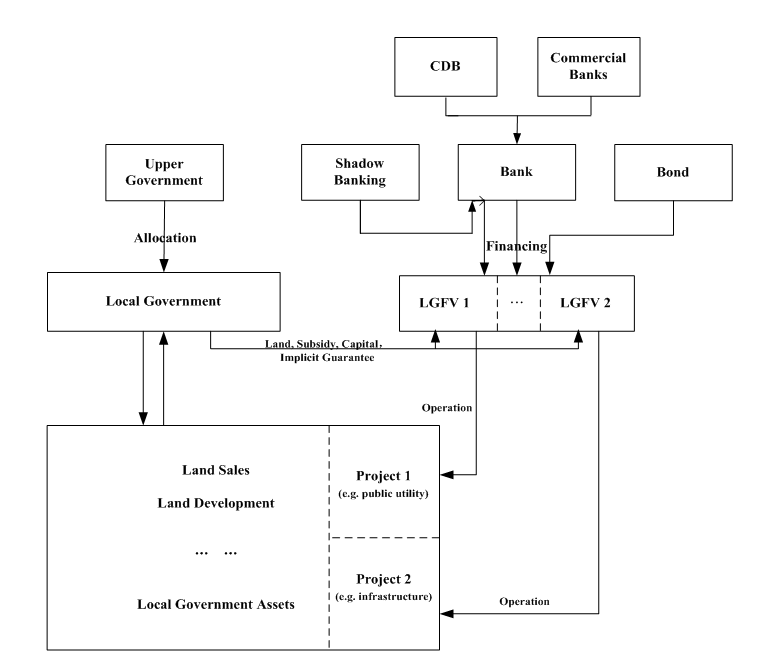

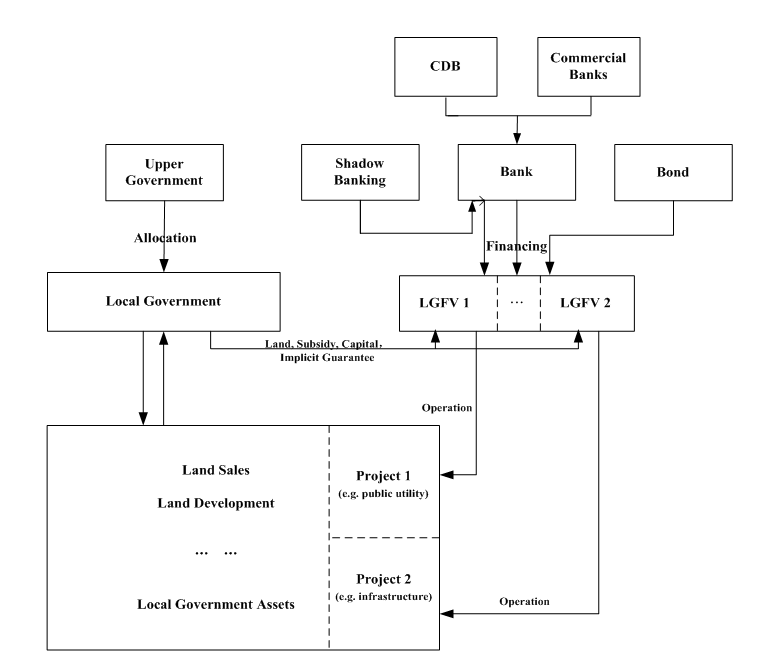

Notes: This figure illustrates the typical flows

of revenues and expenditures of local governments in China. Local

governments receive funding from upper level governments (e.g., central

government) including their share of tax revenues and transfer payments.

They also generate other incomes from land sales and local assets such

as local state owned enterprises. The 1994 budget law prohibited local

governments from engaging in any form of borrowing. Instead of direct

borrowing, therefore, local governments mainly borrowed off-balance

sheet debt from financing vehicles (LGFVs), which are entities fully

owned and operated by local governments. LGFVs raise off-balance sheet

funds for specific projects via bank loans from various entities,

including the China Development Bank, commercial banks, bond issuances,

and the shadow banking system. In 2015, the new budget law allowed the

provincial government to issue municipal bonds. The recent scheme

announced in March 2015 involves swapping the bank loans that local

governments borrowed via their financing vehicles to municipal bonds,

which just became legal in 2014.

Restraining local government borrowing has been an age-old issue for many countries and a hard problem to solve due to the soft budget constraint (Qian and Roland, 1998). Understanding the credit risk and default patterns of local governments in China is important for policy makers and investment professionals, especially at this time as China opens its debt market to foreign investors. While the risks of local government debt are widely discussed in public media, there is rarely any empirical analysis conducted, which is due mainly to data accessibility difficulty created by law and market practices. Before the new budget law took effect in 2015, all local government debts were off-balance sheet and could not be observed by researchers or even policy makers. Figure 3 illustrates the off-balance sheet financing channels of local governments in China. Local governments and lenders including the China Development Bank (CDB) used the LGFVs to bypass legal restrictions on government borrowing and make funds available for local governments.

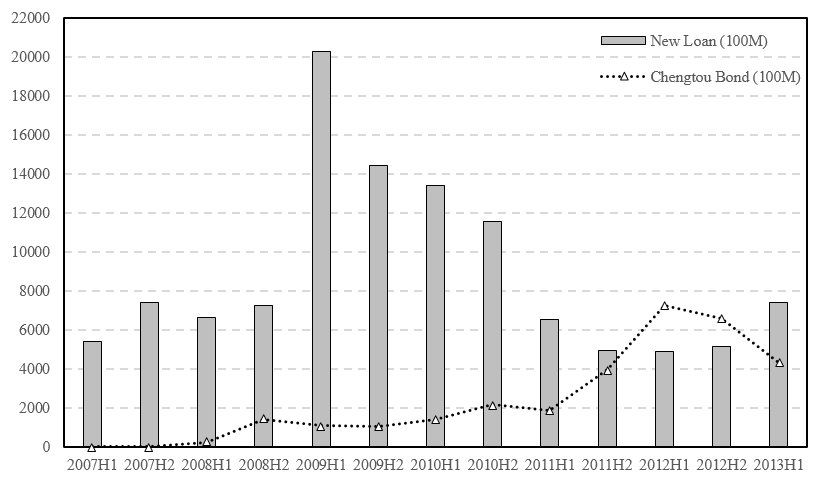

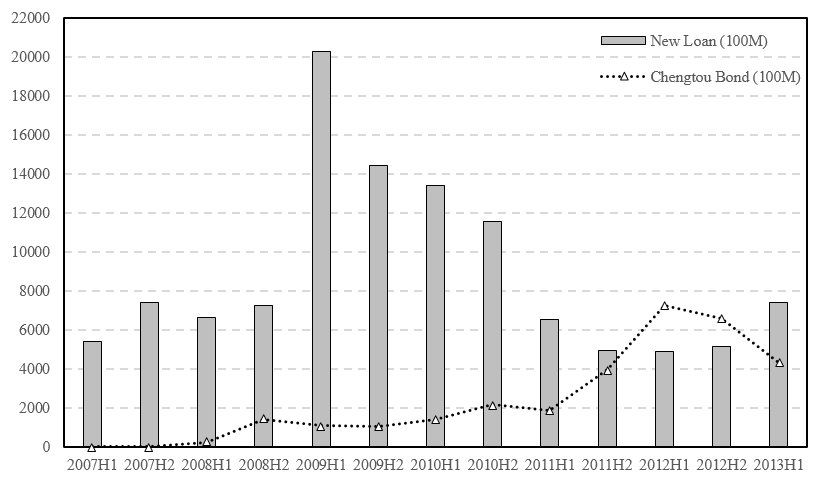

In Gao, Ru, and Tang (2017), we unveil these off-balance sheet local government debts by using a proprietary loan-level dataset covering the period from 2007 to 2013. Bank loans are the dominant financing source for local governments in China during the studied period, as the issuance of “Chengtou” bonds for urban construction and investment only became prominent in late 2011, as shown in Figure 4. Local government borrowing peaked in the first half of 2009 with the new issuance of ¥2,030 billion in bank loans and ¥107 billion in Chengtou bonds.

Figure 4: Debt Financing to China’s Local Governments, 2007-2013.

Notes: This figure plots the semi-annual new debt

issuance by Chinese LGFVs. The grey bars represent the amount of new

issuance of bank loans. The dashed line shows the amount of new issuance

of urban construction and investment (“Chengtou”) bonds. The vertical

axis is in RMB 100 million (亿人民币). Loan data are from the China Banking

Regulatory Commission, and the Chengtou bond data are from the Wind

database.

The dataset that we compiled allows us, for the first time, to explore both the issuance and default patterns of local government bank loans in China. Particularly, we show that there were already a considerable amount of delinquent bank loans to LGFVs. During the period of 2007 to 2013, 1.7% of all matured bank loans in our sample were more than 90 days delinquent, or effectively defaulted according to conventional definition. This default rate for LGFVs is twice as high as the rate for commercial loans (0.9%). Additionally, we find that policy bank loans from the CDB to local governments have a significantly lower default rate (0.3%) than commercial bank loans with similar characteristics (1.8%), as distressed local governments often strategically choose to default on loans from commercial banks. Overall, for the set of LGFVs that have already defaulted on their commercial bank loans, they paid off 97.7% of CDB loans that have the same due time as their defaulted commercial loans. Unlike many other countries (e.g., U.S.A.), there are no “cross default” clauses in loan contracts in China and there is no differential debt seniority in the loan contracts.

The superior loan performance of the CDB loans goes against conventional wisdom that policy banks suffer higher default rates because their borrowers have a soft budget constraint and typically conduct socially beneficial negative NPV projects with positive externalities. We explore the rationales further and find a novel mechanism that hardens the soft budget constraint problem by disciplining the local government borrowers through politicians’ career concerns. In particular, we find that the financial continuation value of the CDB and local politicians’ career concerns play a role in the selective default. The CDB, on average, provides more than 50% of the bank credit to the local governments in China, which is much larger than any commercial banks and makes the CDB the dominant financial source of local governments. In China, local politicians’ career advancements depend largely on local GDP growth (Li and Zhou, 2005). In turn, this makes the CDB credit very important for local economic growth and local politicians’ promotion. Thus, local governments are incentivized to pay back the CDB first in anticipation of securing debt financing from the CDB in the future.

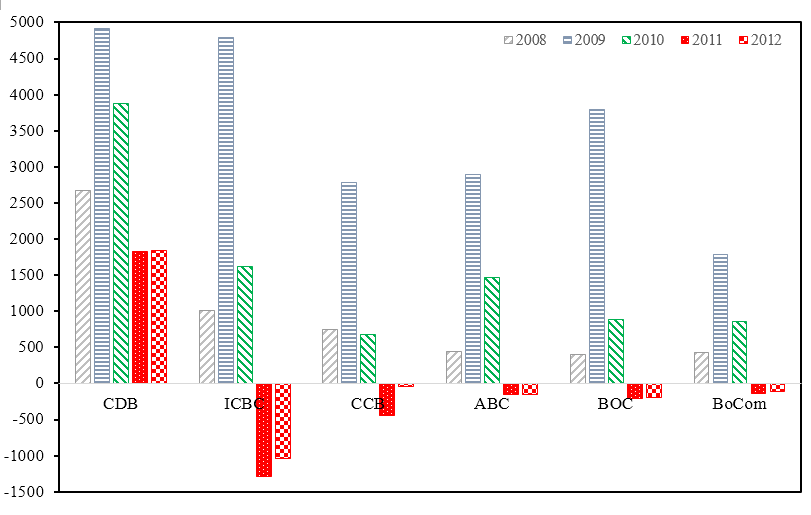

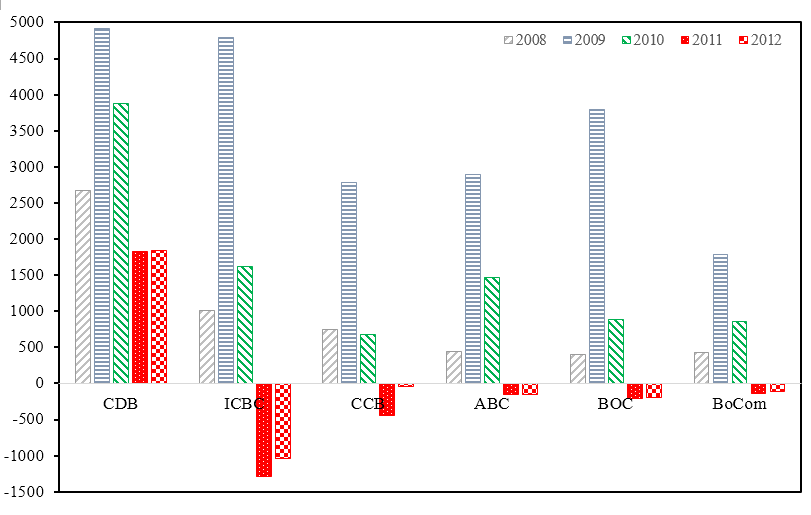

To establish causal effects of the CDB’s financial continuation value on local government selective default, we explore the exogenous variation from the ¥4-trillion stimulus package initiated in November 2008 by the Chinese central government. Before the stimulus, the CDB was the major credit provider for local governments, especially for long-term loans. Figure 5 shows that, during the ¥4-trillion stimulus period, commercial banks substantially increased their lending to the local governments, making the CDB less important. However, after the sudden pull back of the stimulus program in June 2010, all of the big five commercial banks cut their lending to local governments (i.e., their loans outstanding decreased dramatically), and only the CDB continued to increase its lending. This made relationships with the CDB even more important to local governments. We find that during the stimulus period, local governments engaged in significantly fewer selective defaults, but they re-engaged the selective default option by paying back the CDB first after the sudden stimulus retraction. Such evidence provides strong support for our argument that the financial continuation value of the CDB disciplines the local governments/politicians in their loan payment behavior.

Notes: This figure plots the annual change in

outstanding loan balance to LFGVs from 2008 to 2012 for individual

banks. Included are the six biggest LGFV lenders in China: China

Development Bank (CDB), Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC),

China Construction Bank (CCB), Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), Bank of

China (BOC), and Bank of Communications (BoCom). The unit for the

vertical axis of net loan amount is in RMB 100 million. Loan data are

from the China Banking Regulatory Commission and are aggregated to bank

level. In June 2010, the State Council suddenly issued the No. 19

announcement to implement the first official regulation on LGFVs. This

significantly cut down bank lending to LGFVs.

Together with other contemporaneous works (e.g., Ang, Bai and Zhou, 2016; Chen, He, and Liu, 2017; Liu, Lyu and Yu, 2017), we provide the first academic evidence on China’s local government indebtedness. It is the first step towards developing a good understanding of the local government debt landscape in China, especially its default risk. In recent years, the better loan performance of development financial institutions (DFIs) compared to non-DFIs (e.g., commercial banks) is also observed in other countries besides China, such as Japan, Brazil, and India. Our findings, therefore, have broad implications for government financing and debt management for fiscally decentralized countries around the world. Chinese local governments intervene in bank lending through the political system to ease the soft budget constraint problem. Such a politics-finance nexus provides a new debt enforcement mechanism to harden the budget constraint of banks, stemming from the career concerns of local politicians.

Ang, Andrew, Jennie Bai, and Hao Zhou (2016). “The great wall of debt: Real estate, corruption, and Chinese local government credit spreads.” Working Paper.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu (2017). “The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes.” Working Paper.

Gao, Haoyu, Hong Ru, and Dragon Yongjun Tang (2017). “Subnational debt of China: The politics-finance nexus.” Working Paper.

Li, Hongbin, and Li-An Zhou (2005). “Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China.” Journal of Public Economics 89, 1743-1762.

Liu, Xiaolei, Yuanzhen Lyu, and Fan Yu (2017). “Implicit government guarantee and the pricing of Chinese LGFV debt.” Working Paper.

China’s economy has been growing rapidly for the past four decades. It is currently the second largest economy worldwide and contributes approximately 30% of global GDP growth annually. However, this remarkable growth has been fueled by debt financing in recent years, especially local government debt, which—according to official data—increased from ¥1.5 trillion in 2002 to ¥15.3 trillion in 2016. We plot the growth rate of provincial government debt (counting only the explicit debt for which the government is liable) from June 2013 to December 2016 in Figure 1. Guizhou province experienced the fastest growth (88.4%) during this period (from ¥462.3 billion to ¥871.0 billion). The indebtedness of local governments in China in terms of the debt-to-fiscal revenue ratio for each province in China at the end of 2016 is illustrated in Figure 2. The most indebted provinces have ratios above five. The IMF has recently warned China about dangerous debt growth. In 2017, both Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s downgraded the sovereign credit rating of China, and Fitch made a prediction about the first default of bonds issued by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs).

Figure 1: Local Government Debt Growth Rate from June 2013 to December 2016 for Provincial Governments in China.

Figure 2: The Debt-to-Fiscal Revenue Ratios of Provincial Governments in China at the End of 2016.

Figure 3: Local Government Financing and Operating Structure from 1994 to 2014.

Restraining local government borrowing has been an age-old issue for many countries and a hard problem to solve due to the soft budget constraint (Qian and Roland, 1998). Understanding the credit risk and default patterns of local governments in China is important for policy makers and investment professionals, especially at this time as China opens its debt market to foreign investors. While the risks of local government debt are widely discussed in public media, there is rarely any empirical analysis conducted, which is due mainly to data accessibility difficulty created by law and market practices. Before the new budget law took effect in 2015, all local government debts were off-balance sheet and could not be observed by researchers or even policy makers. Figure 3 illustrates the off-balance sheet financing channels of local governments in China. Local governments and lenders including the China Development Bank (CDB) used the LGFVs to bypass legal restrictions on government borrowing and make funds available for local governments.

In Gao, Ru, and Tang (2017), we unveil these off-balance sheet local government debts by using a proprietary loan-level dataset covering the period from 2007 to 2013. Bank loans are the dominant financing source for local governments in China during the studied period, as the issuance of “Chengtou” bonds for urban construction and investment only became prominent in late 2011, as shown in Figure 4. Local government borrowing peaked in the first half of 2009 with the new issuance of ¥2,030 billion in bank loans and ¥107 billion in Chengtou bonds.

Figure 4: Debt Financing to China’s Local Governments, 2007-2013.

The dataset that we compiled allows us, for the first time, to explore both the issuance and default patterns of local government bank loans in China. Particularly, we show that there were already a considerable amount of delinquent bank loans to LGFVs. During the period of 2007 to 2013, 1.7% of all matured bank loans in our sample were more than 90 days delinquent, or effectively defaulted according to conventional definition. This default rate for LGFVs is twice as high as the rate for commercial loans (0.9%). Additionally, we find that policy bank loans from the CDB to local governments have a significantly lower default rate (0.3%) than commercial bank loans with similar characteristics (1.8%), as distressed local governments often strategically choose to default on loans from commercial banks. Overall, for the set of LGFVs that have already defaulted on their commercial bank loans, they paid off 97.7% of CDB loans that have the same due time as their defaulted commercial loans. Unlike many other countries (e.g., U.S.A.), there are no “cross default” clauses in loan contracts in China and there is no differential debt seniority in the loan contracts.

The superior loan performance of the CDB loans goes against conventional wisdom that policy banks suffer higher default rates because their borrowers have a soft budget constraint and typically conduct socially beneficial negative NPV projects with positive externalities. We explore the rationales further and find a novel mechanism that hardens the soft budget constraint problem by disciplining the local government borrowers through politicians’ career concerns. In particular, we find that the financial continuation value of the CDB and local politicians’ career concerns play a role in the selective default. The CDB, on average, provides more than 50% of the bank credit to the local governments in China, which is much larger than any commercial banks and makes the CDB the dominant financial source of local governments. In China, local politicians’ career advancements depend largely on local GDP growth (Li and Zhou, 2005). In turn, this makes the CDB credit very important for local economic growth and local politicians’ promotion. Thus, local governments are incentivized to pay back the CDB first in anticipation of securing debt financing from the CDB in the future.

To establish causal effects of the CDB’s financial continuation value on local government selective default, we explore the exogenous variation from the ¥4-trillion stimulus package initiated in November 2008 by the Chinese central government. Before the stimulus, the CDB was the major credit provider for local governments, especially for long-term loans. Figure 5 shows that, during the ¥4-trillion stimulus period, commercial banks substantially increased their lending to the local governments, making the CDB less important. However, after the sudden pull back of the stimulus program in June 2010, all of the big five commercial banks cut their lending to local governments (i.e., their loans outstanding decreased dramatically), and only the CDB continued to increase its lending. This made relationships with the CDB even more important to local governments. We find that during the stimulus period, local governments engaged in significantly fewer selective defaults, but they re-engaged the selective default option by paying back the CDB first after the sudden stimulus retraction. Such evidence provides strong support for our argument that the financial continuation value of the CDB disciplines the local governments/politicians in their loan payment behavior.

Figure 5: Bank Lending to Local Governments before (2008), during (2009, 2010) and after (2011, 2012) the ¥4-Trillion Stimulus.

Together with other contemporaneous works (e.g., Ang, Bai and Zhou, 2016; Chen, He, and Liu, 2017; Liu, Lyu and Yu, 2017), we provide the first academic evidence on China’s local government indebtedness. It is the first step towards developing a good understanding of the local government debt landscape in China, especially its default risk. In recent years, the better loan performance of development financial institutions (DFIs) compared to non-DFIs (e.g., commercial banks) is also observed in other countries besides China, such as Japan, Brazil, and India. Our findings, therefore, have broad implications for government financing and debt management for fiscally decentralized countries around the world. Chinese local governments intervene in bank lending through the political system to ease the soft budget constraint problem. Such a politics-finance nexus provides a new debt enforcement mechanism to harden the budget constraint of banks, stemming from the career concerns of local politicians.

(Haoyu Gao, Assistant Professor at Central University of Finance and Economics; Hong Ru, Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University; Dragon Yongjun Tang, Professor and Head of Finance Area at the University of Hong Kong.)

Ang, Andrew, Jennie Bai, and Hao Zhou (2016). “The great wall of debt: Real estate, corruption, and Chinese local government credit spreads.” Working Paper.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu (2017). “The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes.” Working Paper.

Gao, Haoyu, Hong Ru, and Dragon Yongjun Tang (2017). “Subnational debt of China: The politics-finance nexus.” Working Paper.

Li, Hongbin, and Li-An Zhou (2005). “Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China.” Journal of Public Economics 89, 1743-1762.

Liu, Xiaolei, Yuanzhen Lyu, and Fan Yu (2017). “Implicit government guarantee and the pricing of Chinese LGFV debt.” Working Paper.

Qian, Yingyi, and Gerard Roland (1998). “Federalism and soft budget constraint.” American Economic Review 88, 1143-1162.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email