Rural-Urban Migration and Market Integration

Reductions in rural-to-urban migration barriers have led to economic gains for both rural origins and urban destinations by reducing information frictions and facilitating the flow of goods and investments between cities and the countryside.

Much of the anecdotal evidence from successful cases of rural economic development involves rural-to-urban migration: migrants learn about urban demand, supply, buyer-seller connections, and sources of capital to seize opportunities back home.

For instance, many of China’s so-called “Taobao villages”—rural marketplaces that have experienced rapid growth by selling to urban centers via e-commerce—have migrants as part of their origin stories. Consider the case of Shaji village in Jiangsu Province, which has been transformed into a major hub for furniture production. According to a report and series of interviews by China Business News (2011), this cluster was started in a small workshop after a migrant worker returned home from Shanghai, where he had visited an Ikea store and brought samples of relatively simple flat-pack self-assembly furniture, well-suited for shipping to customers via e-commerce.

However, the notion that migrant linkages can be a driver of economic development by revealing new opportunities for flows of trade and investments has not featured prominently in the long-standing literature on rural-urban migration (see, for example, Gollin 2014, Lagakos 2020, and Lagakos et al. 2023 for recent reviews).

Do policies aimed at lowering rural-urban migration barriers lead to additional economic gains for rural origins and urban destinations through better market integration in trade and investment? How large are these gains, and is their incidence concentrated among rural origins or urban destinations, reducing or reinforcing incentives for rural-urban migration?

Answering these questions poses some challenges, both in terms of the available data on migration barriers, flows of trade, and investments within countries, and in terms of identification, since many policies that lower migration costs, such as transport investments, could also directly affect bilateral trade and investments, making it difficult to pin down the effect of migrant linkages.

To make progress, we combine a unique collection of microdata from China with a new empirical strategy. We bring to bear data on county-to-county flows of trade, investments, and migration in combination with a digitized database of Hukou reforms implemented by local governments in China over the period from 1978 to 2020. The Hukou system imposes significant costs on those working and living in cities without local residence eligibility, primarily through restrictions on public services, employment rights, and housing markets (see, for example, Bosker et al. 2012, Ngai et al. 2019, and Zhang et al. 2019). We use this database to measure changes in rural households’ eligibility for urban residence registration across bilateral county pairs over time.

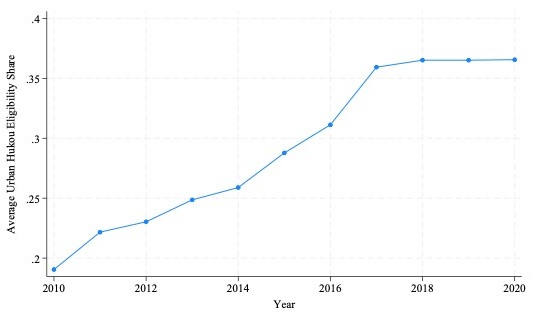

In each year of data between 2010 and 2020, we consider all Hukou reforms that have been passed since 1978 in any one of roughly 1,000 urban county destinations (defined as either county-level cities or urban districts of larger cities), and quantify the proportion of the 2010 population for each of the roughly 1,650 rural origin counties that were eligible to obtain urban Hukou in the destination—fractions from 0 to 1 for each rural origin-by-urban-destination pair and year. We then estimate the effect of changes in rural-urban Hukou eligibility on changes in flows of bilateral trade, investment flows, and migration across county pairs over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hukou eligibility over time

Notes: This figure plots the share of rural origins’ working-age populations, fixed in 2010, who are eligible for urban Hukou registration, averaged across bilateral pairs over time.

A city’s planning commission may determine that more female workers between the ages of 20 and 40 with a minimum of a completed middle-school degree would be beneficial for local industry. In addition, they may decide to implement this new eligibility rule first among rural origins within the same province, before extending it to other regions over time. Such a policy clearly responds to urban labor demand (destination-level shocks that we can capture in our estimation), but it also leads to rich variation in changes of bilateral Hukou eligibility across rural origins over time. This is because the pre-existing composition of workers of a given age, sex, and education differs across regions and because Hukou reforms include geographical restrictions on eligible origin regions.

Implementing this design, we find that a 10 percentage-point increase in a rural origin’s Hukou eligibility to an urban destination—which corresponds to the average increase over the sample period of 2014–2019—increases rural-urban exports and imports by about 1.5% over a four-year period. The effect on urban-to-rural investment inflows is an average 4.5% increase and rural-to-urban investment outflows increase by roughly 3.5% over a five-year period. The effect on rural-urban migration flows is a 3% increase over a five-year period. Bilateral migration stocks increase by about 1.5%. Consistent with the increases in trade and capital flows being driven by better information and reduced matching frictions, we find that the number of unique buyer-seller and investor-investment pairs goes up by about 3% on average, and that Hukou reforms have no significant effect among sellers and buyers with pre-existing bilateral migrant linkages.

Reductions in rural-urban migration barriers, therefore, seem to have promoted market integration between rural and urban regions by facilitating the formation of new buyer-seller and investment linkages that increase flows of trade and capital in both directions. The findings also suggest some complementarity between investment inflows to rural regions and rural exports to cities, including in trade facilitating activities such as warehousing and wholesale and retail trade.

In the final part of the analysis, we then interpret these estimates through the lens of a spatial equilibrium model to answer two main additional questions. The first is to quantify the effect of Chinese Hukou reforms between 2010 and 2020 on migration market access and the resulting knock-on effects on trade and investment market access at the level or regions among the roughly 1,650 rural origin counties in China. Second, while Hukou reforms affect migration costs unilaterally, the evidence suggests that the resulting effects on trade and capital flows are similar in both directions. The second question we then ask is whether the additional gains in market integration through lifting migration restrictions have been stronger among the rural origins or the urban destinations during this period of Hukou reforms.

To answer these questions, we introduce three features of our empirical setting into an otherwise standard quantitative spatial equilibrium model. These are bilateral migration costs that include policy barriers such as Hukou restrictions, mobile capital in addition to labor as inputs to production, and buyer-seller matching frictions in trade and investment transactions following recent work by Eaton et al. (2023). We let these frictions be a function of bilateral migrant stocks, capturing the idea that migrants can reduce information and communication costs (see, for example, Rauch and Trindade 2002).

Combining data and theory, we find that a 10% increase in migration market access among rural counties has on average led to a 1.5% increase in trade market access and a 2% increase in investment market access—a significant amplification of the traditional gains from migration through knock-on effects on market integration in trade and investment. While gains in migration market access are naturally concentrated among the rural origins, we also find that the resulting gains in trade and investment market access are on average larger among the urban destinations. The reason is that Hukou reforms tend to affect multiple rural origin regions for a given urban destination, so that market access gains from reductions in matching frictions tend to be larger among the urban destinations in this policy setting.

Our findings suggest that the recent wave of Chinese Hukou reforms have brought significant additional gains to both rural origins and urban destinations, beyond the traditional gains from migration, by reducing information frictions and facilitating the flow of goods and investments within the country. These knock-on effects have reinforced the incentives for rural-urban migration as they were on average larger among the urban destinations. Our findings complement the rich and long-standing literature on rural-urban migration, informing ongoing policy debates on the role of migration and urbanization for economic development and spatial inequality.

(Dennis Egger, Oxford University; Benjamin Faber, University of California Berkeley; Ming Li, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen; Wei Lin, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen)

References

Bosker, Maarten, Steven Brakman, Harry Garretsen, and Marc Schramm. 2012. “Relaxing Hukou: Increased Labor Mobility and China’s Economic Geography.” Journal of Urban Economics 72 (2–3): 252–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2012.06.002.

China Business News. “Shaji Town’s Online Affairs and Dreams,” China Business News, December 1, 2011, https://www.yicai.com/news/1239088.html.

Eaton, Jonathan, Samuel S. Kortum, and Francis Kramarz. 2023. “Firm-to-Firm Trade: Imports, Exports, and the Labor Market.” Econometrica. Forthcoming.

Gollin, Douglas. 2014. “The Lewis Model: A 60-Year Retrospective.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.3.71.

Lagakos, David. 2020. “Urban-Rural Gaps in the Developing World: Does Internal Migration Offer Opportunities?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (3): 174–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.3.174.

Lagakos, David, Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak, and Michael E. Waugh. 2023. “The Welfare Effects of Encouraging Rural-Urban Migration.” Econometrica 91 (3): 803–37. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA15962.

Ngai, L. Rachel, Christopher A. Pissarides, and Jin Wang. 2019. “China’s Mobility Barriers and Employment Allocations.” Journal of the European Economic Association 17 (5): 1617–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvy035.

Rauch, James E., and Vitor Trindade. 2002. “Ethnic Chinese Networks in International Trade.” Review of Economics and Statistics 84 (1): 116–30. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465302317331955.

Zhang, Jipeng, Ru Wang, and Chong Lu. 2019. “A Quantitative Analysis of Hukou Reform in Chinese Cities: 2000–2016.” Growth and Change 50 (1): 201–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12284.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email