How China’s Business Registration Reform Boosted Entrepreneurship and Productivity

China’s 2014 business registration reform spurred greater market dynamism by lowering entry barriers, which increased firm turnover and allowed smaller yet more productive entrepreneurs to establish new businesses, boosting overall productivity and growth.

New firms are pivotal for economic growth, yet not all new entrants contribute positively. Countries around the world have implemented entry regulations to screen potential entrants and steer them towards productive activities. Despite the long-standing policy interests in entry regulations (Sampi et al. 2023, Brandt et al. 2024), there is a lack of comprehensive evaluation of their broader impacts on firm dynamics and productivity. Evidence from China shows that entry deregulation increased firm entry and exit rates and led to the emergence of smaller, yet more productive, new entrants.

China's 2014 business registration reform removed major entry barriers

Our recent research (Barwick, Chen, Li, and Zhang 2025) examines China's 2014 business registration reform, which was designed to reduce firm registration costs and encourage entrepreneurial activities. Both the scope and the intensity of entry deregulation during 2012–2014 were unprecedented. The reform streamlined the entry registration process and lowered entry barriers in four major ways: the regulations on registered capital were largely lifted, requirements for pre-registration certificates were significantly relaxed, the cumbersome annual inspection system was replaced with a streamlined annual report system, and stringent requirements for a business address were eliminated.

As a result of this reform, China's ranking in the “Starting a Business” index in the World Bank's Doing Business Report leapt from 150th place in 2011 to 27th in 2020, indicating that the entry barriers faced by a prospective entrepreneur in China are now lower than those in the average OECD country.

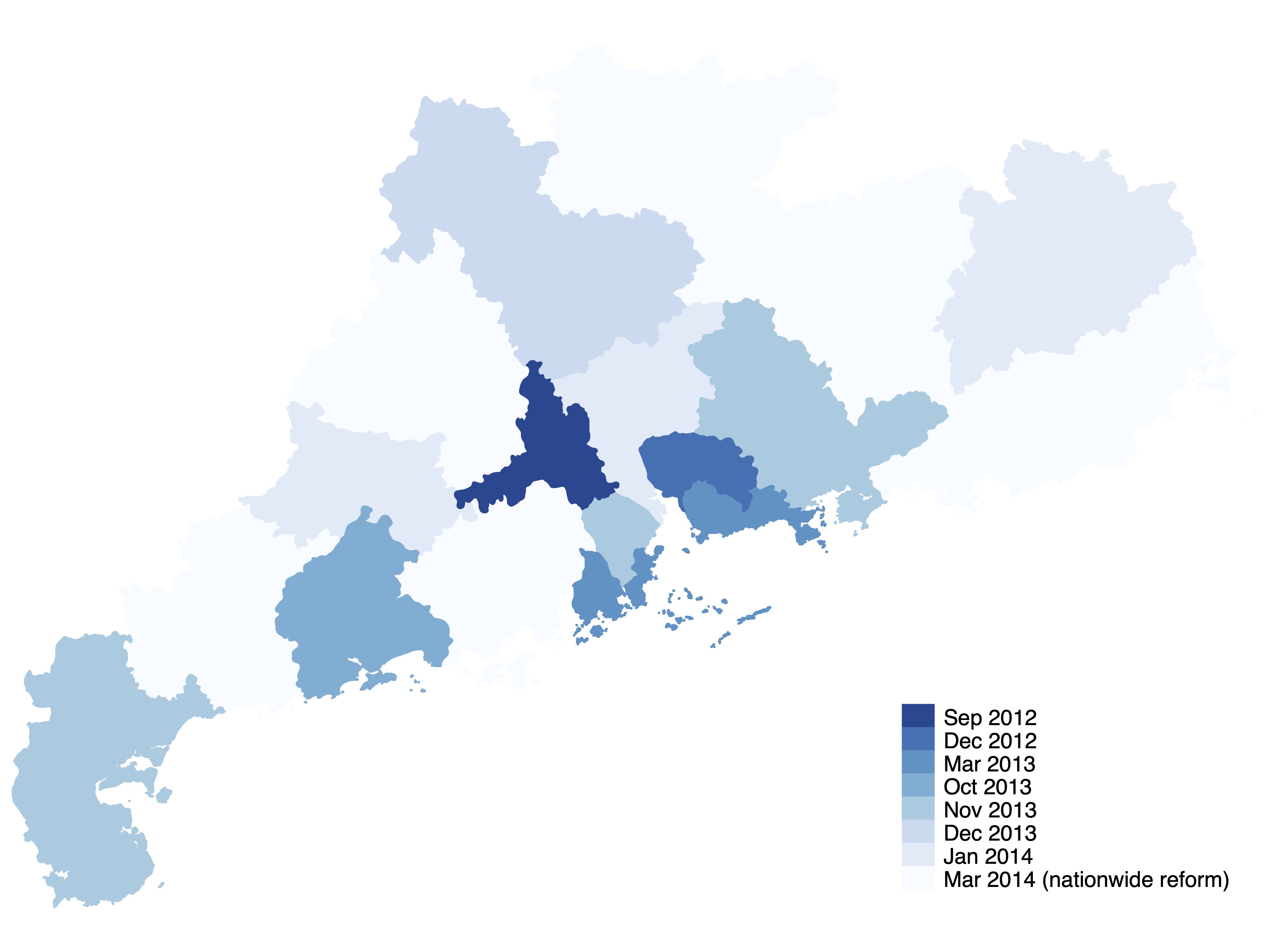

Before implementing the reform nationwide, the government conducted a staggered pilot programme across cities in Guangdong. Guangdong, a coastal province in southern China with 21 cities, is China’s most populous and wealthiest province. The pilot was initiated in 2012 in Dongguan and Foshan and sequentially adopted by ten other cities in 2013 and early 2014. In March 2014, the reform expanded to include the remaining nine cities in Guangdong and the rest of China. The timing of the pilot’s rollout is summarised in Figure 1, with darker colours representing cities that implemented it earlier.

Our analysis leverages the staggered rollout of this pilot programme, taking advantage of the temporal and regional variations in deregulation. We draw on administrative data from firm registration records and annual reports, as well as field enterprise surveys, to evaluate the impact of entry deregulation on firm entry, exit, size distribution, and productivity.

Figure 1: Pilot rollout map in Guangdong

Entry deregulation substantially enhances market dynamism

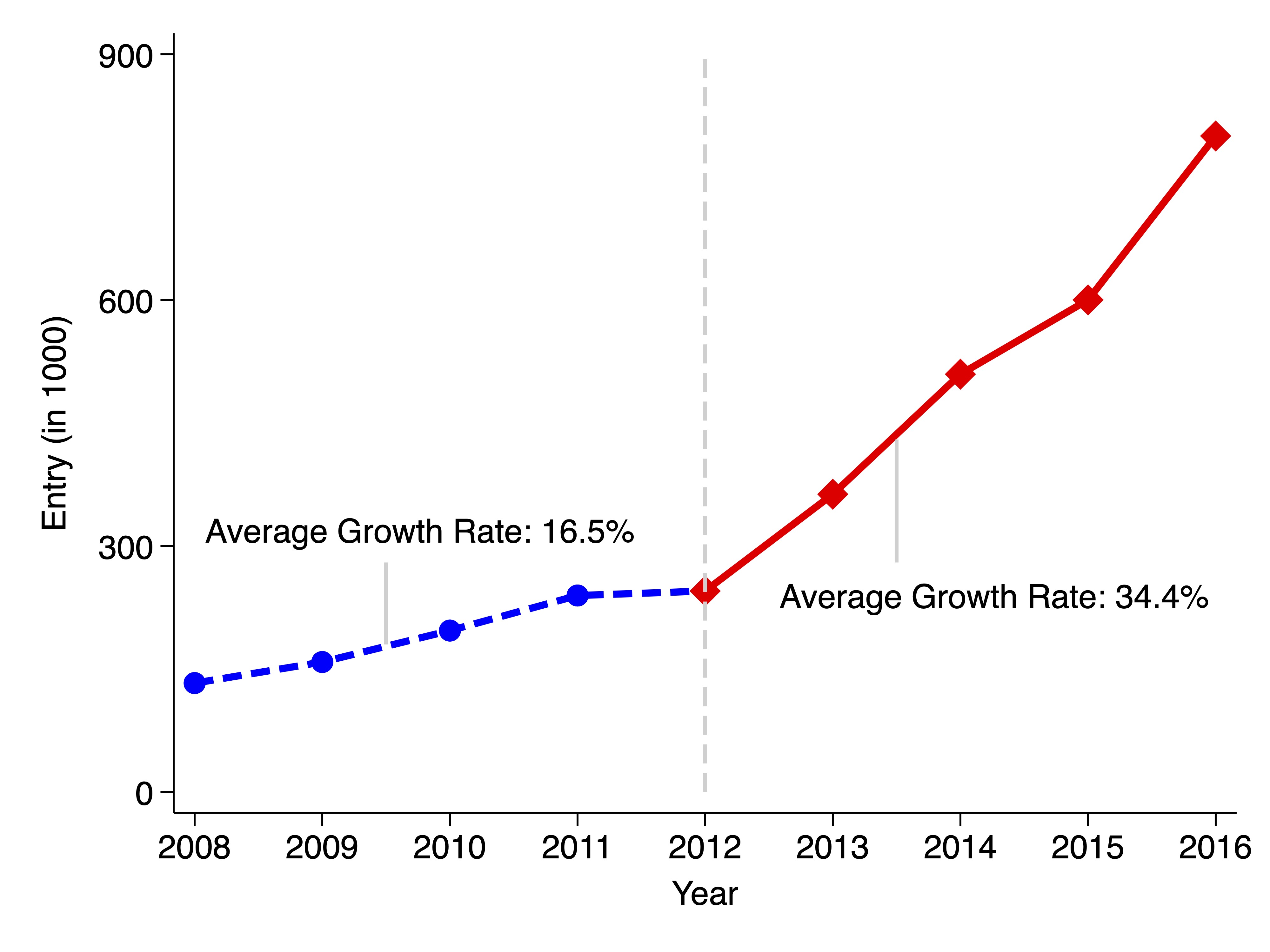

We first examine how the reform affected firm entry using firm registration records. In the wake of the reform, the number of new entrants sharply increased, as shown in Figure 2. The number of new entrants in 2014 was nearly double that in 2012, and the number in 2016 was nearly triple.

Figure 2: Number of new entrants in Guangdong

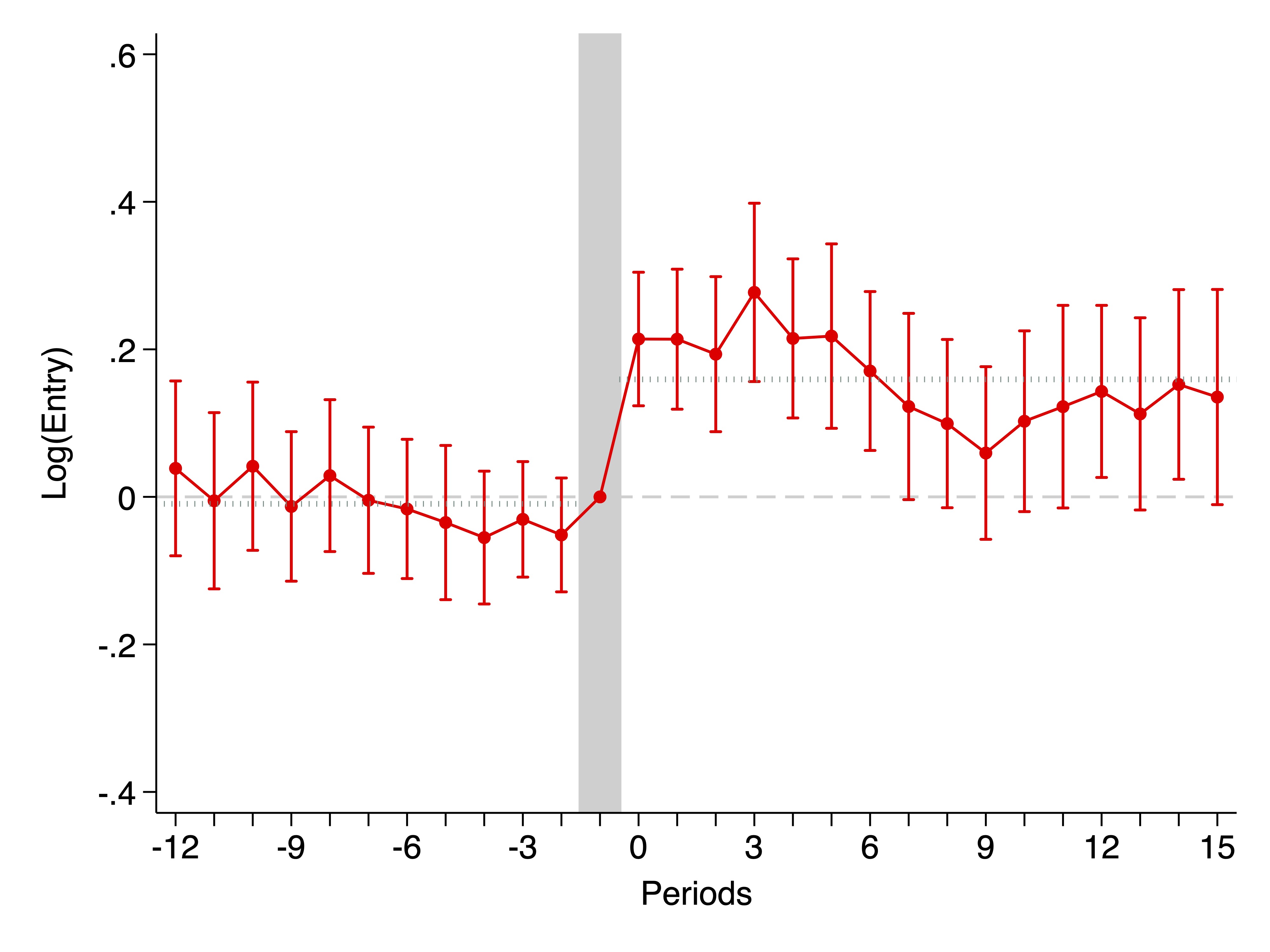

Exploiting the staggered rollout of the pilot programme and an event study framework, we find that China's entry deregulation increased firm entry by 25%. The effect persists over time and is much larger than previous estimates from other countries (Kaplan et al. 2011, Branstetter et al. 2014). The differences are likely due to China’s more comprehensive reform measures – which greatly simplified registration procedures and reduced financial barriers – as well as its rapid implementation and rigorous enforcement (Wei and Sanchez Ortega 2022).

A host of robustness checks suggests that the large increase in firm entry was not driven by the proliferation of shell companies, spin-offs of existing incumbents, reclassification of informal businesses, or relocation of firms from other regions. Instead, most of the newly registered firms represented de novo initiatives by entrepreneurs. Along with higher entry rates, exit rates went up by 8.7%, particularly in more deregulated industries. The combination of rising entry and exit created a higher market turnover rate overall.

Figure 3: The effect of entry deregulation on firm entry

Entry deregulation brings small yet productive new entrants

We next evaluate the effect of entry deregulation on firm size and productivity. The size of new entrants declined in the wake of the reform as deregulation relaxed previously stringent capital requirements, allowing smaller firms to enter. The implication of entry deregulation on firm productivity is ex-ante ambiguous. While entry deregulation could lead to weaker screening and allow unproductive firms to enter, there are two countervailing forces in our context:

1. The reform introduces more intense competition and drives down the profit margins, preventing less productive potential entrants from joining the market.

2. Entry deregulation can potentially change the composition of new entrants and enable productive yet financially constrained entrepreneurs – who would otherwise be unable to enter due to limited resources – to establish new businesses.

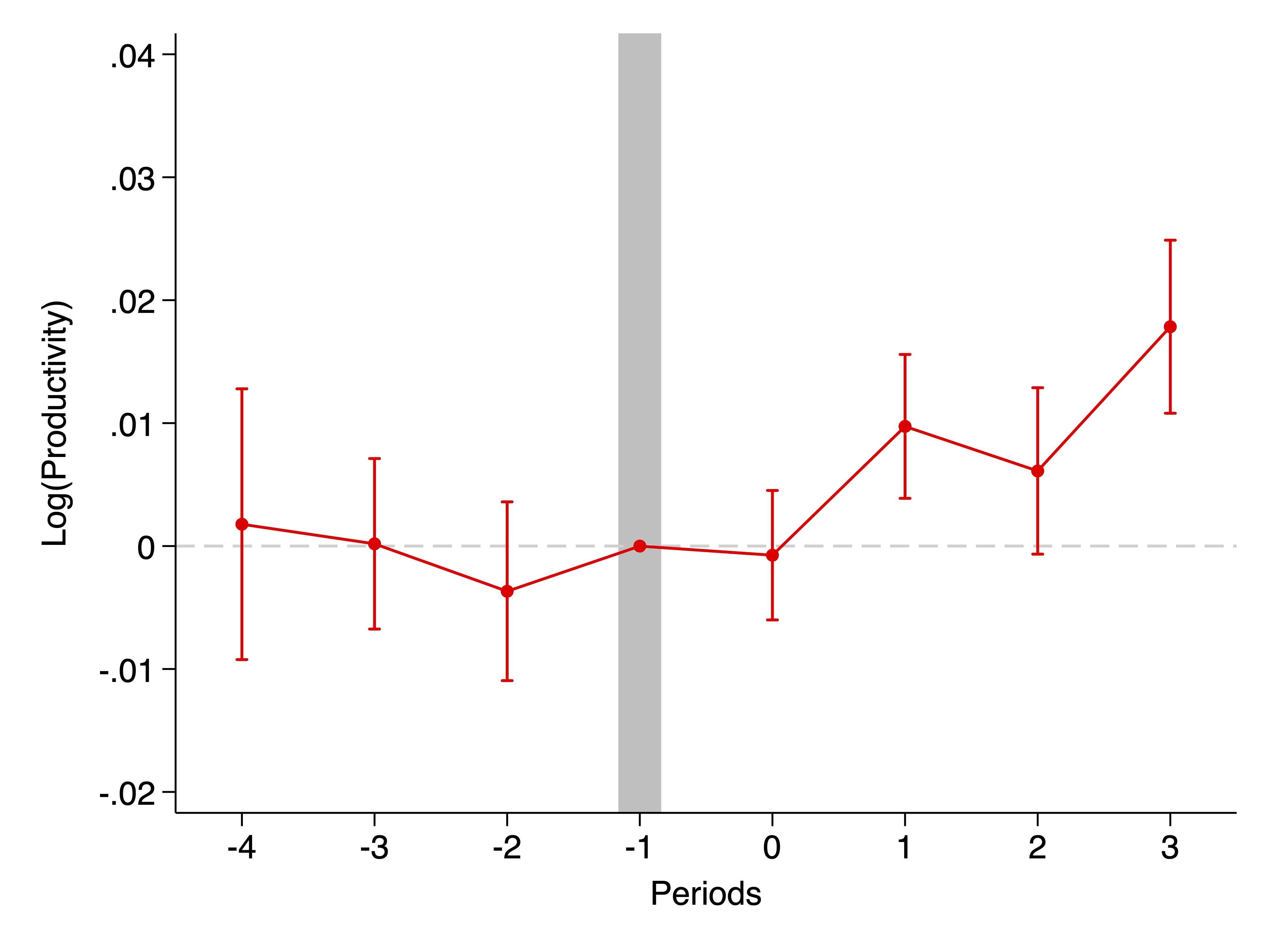

Our analysis shows that the productivity of post-reform entrants was 1.1% higher than the productivity of pre-reform entrants, as shown in Figure 4 – suggesting that intensified market competition and the shift in entrants’ composition outweighed the negative effects of more relaxed regulations.

Figure 4: The effect of entry deregulation on entrants’ productivity

We further examine the underlying channels driving the observed efficiency gains in entrants' productivity. Our analysis provides strong evidence that the alleviation of financial constraints led to significant changes in entrant composition:

· Survey data suggests that fewer entrepreneurs borrowed from friends, relatives, or financial institutions to finance startup costs post-reform.

· Entry deregulation opened opportunities for less educated and younger entrepreneurs, who were more likely to be financially constrained.

· The productivity improvement was greater for smaller and private firms, as well as those in industries that had previously required higher levels of registered capital or operated in markets with more limited access to finance.

We also quantify the contribution of entry deregulation to the aggregate economy. These deregulation-induced newly registered firms increased Guangdong's total employment and revenue in the manufacturing sector by 2.5% and 1.8%, respectively, in the first three years after the reform and are projected to generate 14.4% and 11.1% additional employment and revenue, respectively, in ten years.

Policy implications for firms

To summarise, we find significant impacts of entry deregulation along multiple margins. As a result of the reform, both entry and exit rates have increased. New entrants have become more productive and made greater contributions to overall productivity growth. These results suggest that distortive regulatory restrictions may deter productive entrepreneurs from starting businesses. Relaxing entry hurdles could potentially improve market turnovers and encourage the entry of productive firms who may otherwise be excluded. China’s experience also offers a valuable lesson for other developing countries that are still imposing stringent entry regulations and struggling with stagnant market dynamism.

(This is reposted from an article originally posted at VoxDev.)

References

Barwick, P J, L Chen, S Li, and X Zhang (2025), “Entry deregulation, market turnover, and efficiency: China’s business registration reform,” Review of Economics and Statistics: 1–46.

Branstetter, L, F Lima, L J Taylor, and A Venâncio (2014), “Do entry regulations deter entrepreneurship and job creation? Evidence from recent reforms in Portugal,” The Economic Journal 124(577): 805–832.

Brandt, L, G Kambourov, and K Storesletten (2024), “How do new firms shape regional economic growth in China?,” VoxDev.

Kaplan, D S, E Piedra, and E Seira (2011), “Entry regulation and business start-ups: Evidence from Mexico,” Journal of Public Economics 95(11–12): 1501–1515.

Sampi, J, M Schiffbauer, and J Coronado (2023), “Removing local barriers to entry can boost productivity growth: Evidence from Peru,” VoxDev.

Wei, W, and L A Sanchez Ortega (2022), “Business registration reforms in China,” Unpublished manuscript.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email