Monetary Policy in China: A Trade-Off Between Transmission and Stability?

We explore how China’s shift toward interest-rate-based monetary policy faces an inherent trade-off. When non-state banks turn to wholesale funding, monetary policy easing is transmitted more effectively to productive firms, but the banking system also becomes more fragile in economic downturns. Our findings suggest that China’s regulators must strike a careful balance between achieving policy effectiveness and safeguarding financial stability.

Across the globe, central banks face a common dilemma: monetary policies that stimulate credit and growth can also increase systemic risk. Scholars such as Bernanke and Blinder (1988, 1992) emphasize how banks amplify monetary policy shocks, while Brunnermeier and Sannikov (2014) show how leverage can destabilize the financial system. This tension between effective policy transmission and systemic stability has become a serious challenge for modern central banking, yet the literature has not formally linked these two issues within a single framework.

We use China as a vivid illustration of this dilemma. Although China experienced large-scale bank bailouts in the 1990s, the subsequent decades of rapid growth, high savings rates, and extensive state involvement in the financial sector led many to believe that the system was insulated from major financial turmoil. The collapse of Evergrande between 2021 and 2023 and the subsequent bailouts of several regional banks shattered this perception. These events exposed hidden vulnerabilities, particularly among non-state banks heavily exposed to real estate borrowers. They also raised a fundamental question: as China shifts toward interest-rate-based monetary policy, how can it strike a balance between transmission effectiveness and financial stability?

Our research (Chen et al. 2025) shows that the interbank wholesale funding market sits at the center of this trade-off. Using bank-level data from 2013 to 2019, we find that wholesale funding enhances the pass-through of monetary policy easing to lending by non-state banks, but at the same time makes them more fragile during economic downturns. While our structural model is motivated by China’s evidence and institutions, the framework is general, and the broader lesson is clear: tighter regulation of interbank funding weakens monetary policy transmission, but reduces systemic risk.

From quantity to interest-rate-based policy

China has gradually shifted from quantity-based tools (such as targeting M2) toward an interest-rate-based framework. Since 2015, the seven-day interbank repo rate (R007) has become the operational target of the People’s Bank of China (PBC). Yet this transition is incomplete, because while interbank rates are liberalized, deposit rates remain subject to ceilings imposed through self-regulatory mechanisms among large banks.

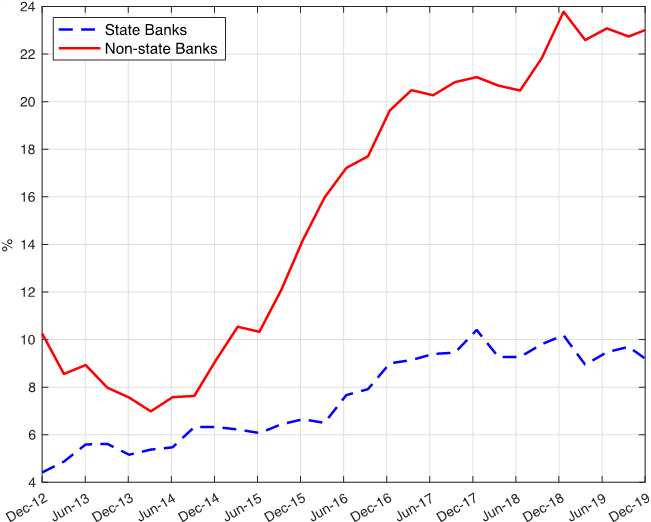

This dual-track system creates asymmetries between bank types. State-owned banks, with nationwide branch networks and implicit government backing, enjoy a nearly unlimited capacity to attract deposits. By contrast, non-state banks—joint-stock, city commercial, and rural commercial banks—face tighter constraints. To expand their balance sheets during periods of monetary easing, they turn to wholesale funding, borrowing from the interbank market or issuing negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs). By 2017, wholesale funding made up more than 20% of liabilities for many non-state banks, compared to under 10% for state banks.

While these institutional features are distinct to China, the underlying mechanism is more general. Our framework applies whenever different groups of banks face sharply different deposit demand elasticities. China is a natural case study because the asymmetry between state and non-state banks is particularly stark, but the same logic extends to other economies with segmented banking sectors. To demonstrate the mechanism in action, we turn to China’s experience.

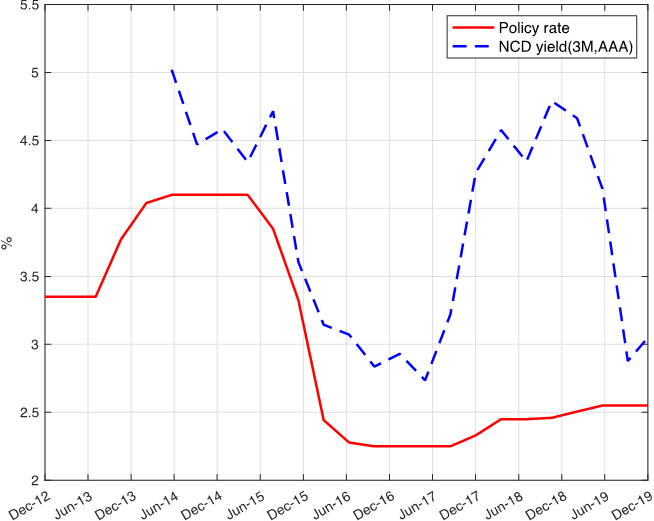

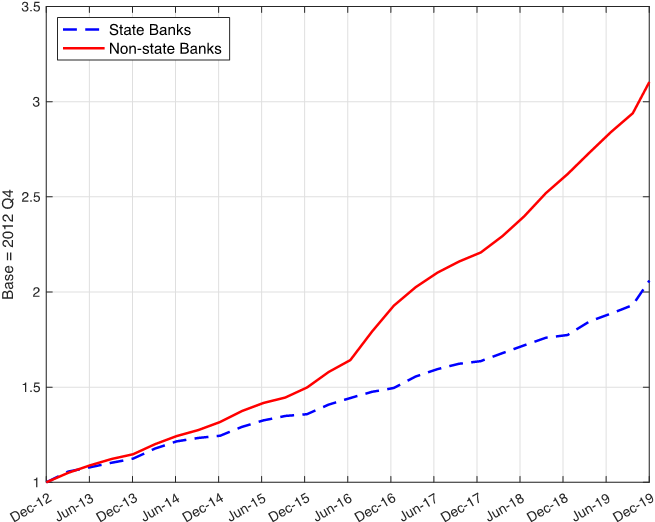

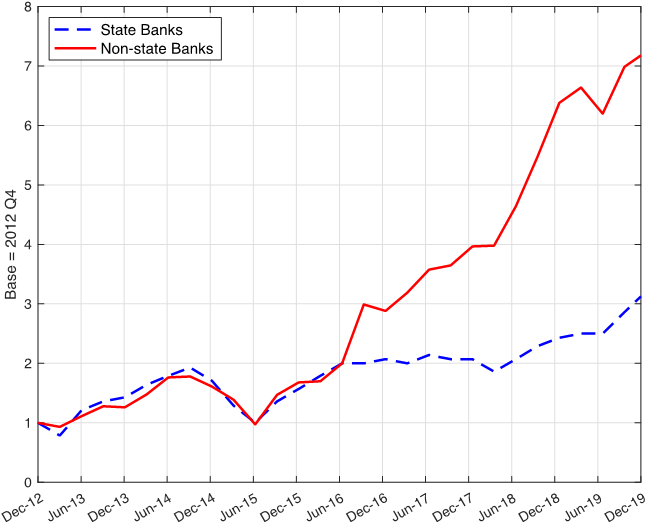

Figures 1–4 illustrate this divergence. As policy rates declined after 2014, non-state banks dramatically expanded wholesale funding and lending, but also became more exposed to systemic risk, especially after 2016. By contrast, state banks’ reliance on wholesale funding remained limited, and their systemic risk stable. We measure systemic risk using SRISK, an index of expected capital shortfalls developed by Brownlees and Engle (2017). It reflects how much capital a bank would need in a market downturn, thus providing a forward-looking measure of vulnerability.

Figure 1. Monetary policy rate and wholesale funding cost. This figure shows the policy rate and the cost of wholesale funding (NCD yields).

Figure 2. Wholesale funding share (state vs. non-state banks). The figure shows the share of wholesale funding in liabilities for state vs. non-state banks.

Figure 3. Loans (state vs. non-state banks). The figure shows lending growth by state vs. non-state banks.

Figure 4. Systemic risk (state vs. non-state banks). The figure shows systemic risk (SRISK) for state vs. non-state banks

Identifying monetary policy shocks

A central element of our analysis is the construction of interest-rate-based monetary policy shocks. Unlike in advanced economies, China’s monetary policy reflects both inflation and growth targets, with asymmetric responses depending on whether GDP growth falls below official goals. To isolate exogenous policy shocks, we estimate a rule for the seven-day repo rate (R007) and then take the residuals as shocks. That is, we regress the seven-day repo rate (R007) on inflation and the GDP growth deviation from official targets, allowing for asymmetric responses when growth falls short of the target. The residuals from this regression represent exogenous monetary policy shocks.

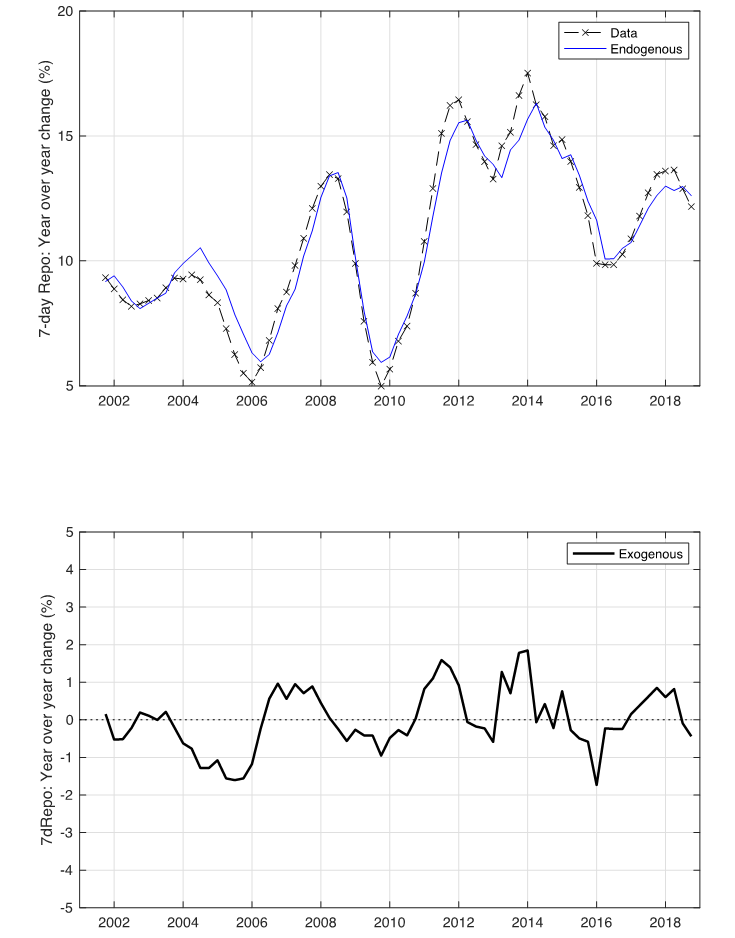

Figure 5 shows how the endogenous (systematic) component of R007 closely tracks the observed policy rate, while the residuals capture the exogenous shocks. This decomposition allows us to measure the causal effects of monetary policy easing on banks’ funding and lending behavior.

Figure 5. Endogenous vs. exogenous components of the seven-day repo rate (R007).

The figure shows how much of the movement in the seven-day repo rate can be explained by inflation and output growth (endogenous component), and how much represents unpredicted monetary policy shifts (exogenous component).

This identification strategy is crucial because it allows us to move beyond correlations and uncover the causal effects of monetary policy. By isolating exogenous shifts in the policy rate, we can trace how monetary policy works through different types of banks and, ultimately, how it shapes both credit allocation and systemic risk.

The liquidity reallocation channel

Our empirical analysis finds that when the PBC lowers policy rates, non-state banks significantly expand their reliance on wholesale funding. This reliance, in turn, amplifies the transmission of monetary policy to their lending. For example, our estimates show that a one-percentage-point decrease in the policy rate leads to roughly a 0.3–0.5 percentage point increase in the loan-to-asset ratio at non-state banks with higher wholesale funding shares.

This mechanism, which we term the liquidity reallocation channel, operates as follows. Policy easing reduces the cost of reserves, encouraging all banks to demand more deposits. State banks can satisfy this demand through their broad access to household deposits, but non-state banks are constrained by the deposit rate ceiling. To continue lending, they instead borrow from the interbank market. State banks, acting as net deposit recipients, reallocate liquidity to non-state banks through interbank lending. Other PBC facilities, such as the Medium-Term Lending Facility, also provide funding, but the interbank market remains the primary channel of monetary policy transmission, especially for non-state banks with limited deposit-raising capacity (Jiang et al. 2023).

This process reallocates capital from less productive state-owned enterprises (typically served by state banks) to more productive private firms (primarily borrowers of non-state banks). In the short run, this enhances total productivity and boosts output. Our structural model shows that such liquidity reallocation raises GDP and consumption in response to monetary policy easing.

Although these dynamics are shaped by China’s unique dual-track system, the implication is broader: When some banks have less ability to attract deposits than others because of differences in deposit demand elasticities, interbank funding allows liquidity to flow toward banks that lend more productively. China thus illustrates a mechanism that could apply in other banking systems with similar asymmetries.

The systemic risk trade-off

While wholesale funding strengthens monetary policy transmission, it also introduces fragility. Unlike deposits, wholesale funding is short-term, more volatile, and lacks explicit guarantees. Banks that heavily rely on it face rollover risks when economic conditions deteriorate.

Our analysis of expected capital shortfalls (SRISK) from 2013 to 2019 reveals that non-state banks with greater wholesale funding exposure experienced sharp increases in systemic risk during the post-2017 slowdown. By contrast, state banks’ systemic risk remained largely unaffected.

During downturns, rising credit risk premium raises the cost of wholesale borrowing for non-state banks. As their net worth declines, they face tighter funding constraints, triggering a reallocation of capital back toward less productive state banks. Such a negative shock is amplified, leading to lower output and higher vulnerability to runs. The bailouts of Baoshang, Hengfeng, and Jinzhou banks in 2019 illustrate how these risks can crystallize.

In May 2019, Baoshang Bank was taken over jointly by the PBC and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission due to what regulators described as “serious credit risks.” Hengfeng Bank was rescued with a major capital injection after corruption scandals and rising non-performing loans, while Jinzhou Bank required government support following severe distress. These episodes highlight that expansion fueled by wholesale funding can quickly become a flashpoint for systemic instability when growth slows and credit risks rise. More generally, whenever banks rely heavily on short-term wholesale funding, downturns can amplify systemic risk.

Policy implications: Regulating the interbank market

Our findings highlight a dilemma for regulators. On the one hand, wholesale funding allows monetary policy to be more effective by channeling liquidity toward productive firms. On the other hand, it makes the banking system more vulnerable to shocks.

Our counterfactual analysis shows that imposing ceilings on wholesale funding channeled to non-state banks can substantially reduce systemic risk. In our calibrated model, such regulation cuts the probability of banking runs from once every 12 years to once every 78 years. The same policy, however, reduces the output gains from monetary policy easing by nearly half. The optimal regulatory design, therefore, involves a compromise: modest restrictions that preserve much of the liquidity reallocation channel while mitigating severe systemic risk.

The Chinese case sheds light on the broader debate over how monetary and macroprudential policies interact. In advanced economies, wholesale funding is often associated with shadow banking and instability (Acharya et al. 2017; Brunnermeier and Sannikov 2014). In China, by contrast, institutional features such as deposit rate ceilings make wholesale funding a necessary complement to traditional deposits, strengthening monetary policy transmission under normal conditions. In both cases, the trade-off remains: the very mechanism that improves monetary effectiveness can undermine financial stability in economic downturns.

Going forward

Our research shows that monetary policy in China operates through a double-edged mechanism. It reallocates liquidity from state to non-state banks, enhancing transmission and supporting more efficient credit allocation. Yet the same mechanism magnifies systemic vulnerabilities, especially when growth slows and credit risks rise.

China offers a vivid case, but in any economy where banks face different deposit constraints, monetary policy transmission and financial stability will be linked by the same underlying trade-off. Designing macroprudential tools that strike a balance between these competing objectives is thus crucial for China as well as other economies facing similar tensions.

References

Acharya, Viral V., Lasse H. Pedersen, Thomas Philippon, and Matthew Richardson. 2017. “Measuring Systemic Risks.” Review of Financial Studies 30: 2–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhw088.

Bernanke, Ben S., and Alan S. Blinder. 1988. “Credit, Money, and Aggregate Demand.” American Economic Review 78 (2): 435–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1818164.

Bernanke, Ben S., and Alan S. Blinder. 1992. “The Federal Funds Rate and the Channels of Monetary Transmission.” American Economic Review 82 (4): 901–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117350.

Brownlees, Christian, and Robert F. Engle. 2017. “SRISK: A Conditional Capital Shortfall Measure of Systemic Risk.” Review of Financial Studies 30 (1): 48–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhw060.

Brunnermeier, Markus K., and Yuliy Sannikov. 2014. “A Macroeconomic Model with a Financial Sector.” American Economic Review 104 (2): 379–421. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.2.379.

Chen, Kaiji, Jue Ren, and Tao Zha. 2018. “The Nexus of Monetary Policy and Shadow Banking in China.” American Economic Review 108 (12): 3891–3936. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20170133.

Chen, Kaiji, Yiqing Xiao, and Tao Zha. 2025. “A Trade-Off Between Monetary Policy Transmission and Systemic Risk in China.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 34056. https://www.nber.org/papers/w34056.

Jiang, Hai, Chao Yuan, and Zhitao Lin. 2023. “Interbank Liquidity Transmission and the Credit Channel of Monetary Policy in China.” Research in International Business and Finance 66: 102016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.102016.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email