Money or Monitoring: What Motivates Workers in China?

Higher compensation incentivizes workers to work additional hours and stay at the firm, while increased monitoring enhances work quality but also increases quitting by workers.

Firms in developing countries experience significantly higher worker turnover rates than those in developed countries. Recent evidence indicates that job-hopping is five times more common in developing countries compared to developed ones (Donovan et al. 2023). This high turnover may contribute to the substantial productivity gaps observed between rich and poor nations, as frequent employee movement can lead to increased hiring and training costs and lower productivity levels among new workers. Consequently, attracting the best talent and motivating effort after hiring remains a critical challenge for firms. Common strategies to address this include offering higher wages or increasing monitoring. Numerous studies have examined the effectiveness of these approaches (Guiteras and Jack 2018, Kim et al. 2020, de Ree et al. 2018, DellaVigna et al. 2022, Jackson and Schneider 2015). However, most of this research focuses on government, NGO, or casual day labor settings, and often analyzes each strategy in isolation. There is limited understanding of what works for private sector firms, and how monitoring interacts with compensation in addressing these issues.

The study: Testing two management strategies

In this study, we conducted field experiments with newly hired automobile manufacturing workers in China, implementing two main interventions. In the first intervention, the compensation experiment, the control group received the firm’s standard package, while the treatment group was offered an enhanced package that include a one-time lump-sum signing bonus of 1,600 RMB. Workers in our partner firm were paid primarily through an hourly wage, and the signing bonus increased their total compensation by approximately 16% over three months. To distinguish between the effects of selection (who joins) and effort on the job, we used a two-stage design. After interviews but before starting the job, the treatment group received the signing bonus one month after starting, conditional on remaining with the firm. One month after starting, we further randomized the control group into two subgroups: one received an unexpected bonus of the same amount at the same time, designed to capture the effect of incentives on effort (moral hazard). This surprise bonus subgroup joined the firm without knowing about this additional bonus, allowing us to separate effort effects from selection effects in the group offered the signing bonus before joining.

In the second intervention, we collaborated with the firm on a monitoring experiment. Among the same workers in the first intervention, we randomly assigned a subset to increased monitoring through additional visits by an independent team. This design allowed us to evaluate separately the effects of compensation and monitoring.

The effects of financial incentives

The results for financial incentives were clear and powerful. We found that offering a signing bonus significantly increased the number of people who accepted a job offer by 10.6 percentage points, compared to a 68% acceptance rate in the control group. The bonus also significantly reduced worker quit rates. For a company facing high turnover—with roughly 25% of new hires leaving within the first 10 days—this improved retention meant substantial cost savings on recruiting and training new employees.

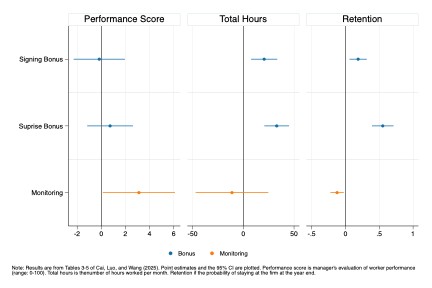

Interestingly, the bonuses influenced a specific type of effort. Figure 1 plots the estimated effects of the bonus and monitoring treatments on worker performance, hours worked, and retention rate. Workers who received the bonus—whether they knew about it when they were hired or received it as a surprise a month later—worked more hours, leading to a significant increase in their monthly earnings. However, this extra time did not lead to better performance ratings from their managers or plant supervisors. This is consistent with a “gift-exchange” dynamic, where workers reciprocate the company’s generosity by putting in more time (Akerlof 1982, DellaVigna et al. 2022), rather than improving the quality of their tasks. Longer hours may lead to fatigue and reduced work quality, or workers may have struggled to improve work quality without additional feedback.

The effects of monitoring

The monitoring experiment, by contrast, had completely different effects. When new hires were subjected to more frequent and formal supervision—one additional visit per week from an external monitoring staff member—their work quality improved. Their managers gave them higher evaluation scores, and they received more performance bonuses. The increased oversight appeared to enhance the quality of their work, likely due to the specific feedback and guidance provided by the monitors. But this gain came with a major downside: these workers were also significantly more likely to quit. This is partially offset by the bonus for workers who receive both additional monitoring and a bonus. Workers seemed to find the additional scrutiny undesirable (Friebel et al. 2024), and it drove them to leave the company more often.

Figure 1: The Effects of Bonus and Monitoring on Performance, Hours, and Retention

Cost-benefit analysis

When we analyzed the costs and benefits, bonuses clearly proved more effective. The savings from reduced turnover and the value generated by workers putting in longer hours far exceeded the cost of the bonus payments. In contrast, monitoring was less advantageous; the expenses associated with replacing workers who quit due to increased supervision outweighed the performance gains. In fact, the costs of the monitoring exceeded the benefits, resulting in a net loss for the firm.

Conclusion and policy impact

Our findings demonstrate that financial incentives and monitoring influence different aspects of worker behavior. Signing bonuses are cost-effective strategies for increasing worker retention and effort, making them particularly valuable in high-turnover sectors. They encourage longer participation without compromising overall productivity, thus helping firms reduce recruitment and training costs. Conversely, enhanced monitoring can improve worker performance through increased oversight and feedback, but it also raises attrition rates and associated costs, which diminishes its overall cost-effectiveness.

Therefore, policymakers and managers should prioritize financial incentives to attract and retain workers, especially where labor stability is critical. When aiming to improve work quality, monitoring can be useful, but additional strategies should be developed to mitigate its negative effects on retention, such as combining oversight with supportive feedback or performance-based rewards. Ultimately, a balanced approach that leverages the strengths of both interventions, while carefully managing their drawbacks, is essential for fostering a productive and stable workforce.

References

Akerlof, George A. 1982. “Labor Contracts as Partial Gift Exchange.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 97 (4): 543–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/1885099.

Cai, Jing, Sai Luo, and Shing-Yi Wang. 2025. “Money or Monitoring: Evidence on Improving Worker Effort.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 33977. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33977.

De Ree, Joppe, Karthik Muralidharan, Menno Pradhan, and Halsey Rogers. 2018. “Double for Nothing? Experimental Evidence on an Unconditional Teacher Salary Increases in Indonesia.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (2): 993–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx040.

DellaVigna, Stefano, John A. List, Ulrike Malmendier, and Gautam Rao. 2022. “Estimating Social Preferences and Gift Exchange at Work.” American Economic Review 112 (3): 1038–74. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190920.

Donovan, Kevin, Will Jianyu Lu, and Todd Schoellman. 2023. “Labor Market Dynamics and Development.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 138 (4): 2287–2325. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjad019.

Friebel, Guido, Matthias Heinz, Mitchell Hoffman, Tobias Kretschmer, and Nick Zubanov. 2024. “Is This Really Kneaded? Identifying and Eliminating Potentially Harmful Forms of Workplace Control.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 34122. https://www.nber.org/papers/w34122.

Guiteras, Raymond P., and B. Kelsey Jack. 2018. “Productivity in Piece-Rate Labor Markets: Evidence from Rural Malawi.” Journal of Development Economics 131: 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.11.002.

Jackson, C. Kirabo, and Henry S. Schneider. 2015. “Checklists and Worker Behavior: A Field Experiment.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (4): 136–68. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140044.

Kim, Hyuncheol Bryant, Seonghoon Kim, and Thomas T. Kim. 2020. “The Role of Career and Wage Incentives in Labor Productivity: Evidence from a Two-Stage Field Experiment in Malawi.” Review of Economics and Statistics 102 (5): 839–51. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00854.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email