Increasing government transparency reduced pollution violations and improved air quality in China

Government transparency helps bridge gaps between environmental laws and actual practices, improving health and environmental quality broadly.

Transparency—the public release of information that is useful for evaluating the performance of organisations—is often promoted as a way to address failures in implementing different types of policies worldwide (Kim et al. 2005). It gives interested parties the information they need to pressure governments for better outcomes, including through lawsuits, complaints, and programmatic voting. International treaties (UNECE n.d.), international organisations (Gupta and Mason 2014), national governments (Berliner 2014), and non-governmental organisations (Dethier et al. 2021) have all promoted transparency practices to improve policy outcomes. Transparency can activate public attention, support the activities of nongovernmental organisations, facilitate political oversight between different levels of government, and improve policy coordination across governmental units.

However, since effective governments have more incentives to adopt transparent practices, the causal relationship between transparency and policy outcomes is difficult to disentangle. Governments have more reason to be transparent when they perform well, when they have greater capacity, and when there are political demands for accountability from powerful actors. These factors may independently cause better policy performance, undermining claims that transparency causes improved policy implementation. Nonetheless, transparency initiatives are increasingly being launched worldwide, making it critical to disentangle the relationship between transparency and policy outcomes.

Failure to implement pollution regulations harms human health

We study governmental transparency as it is relevant to air pollution in China. Air pollution poses a grave challenge to human health across the globe. Annually, it is responsible for over 5.55 million premature deaths worldwide (Lelieveld et al. 2019). However, as with many other areas of pressing societal concern, the crux of this issue is often not the absence of regulations, but rather the failure of governments to effectively implement existing environmental regulations (Greenstone and Jack 2015). In the context of air pollution, government failure to enforce compliance has been documented across several areas, including industrial emissions (Duflo et al. 2018, Buntaine et al. 2024), ambient air quality standards (Zou 2021), crop burning (Dipoppa and Gulzar 2024), and vehicular emission (Oliva 2015).

If we prompt local governments to become more transparent about their management of pollution, can we see a measurable impact on air quality To study this question and the causal relationship between transparency and environmental outcomes, we set up an experiment in China to compare air quality and pollution violations in cities that were prompted to become more transparent to a control group that was not (Liu et al. 2025).

Publicly rating governments increased transparency in China

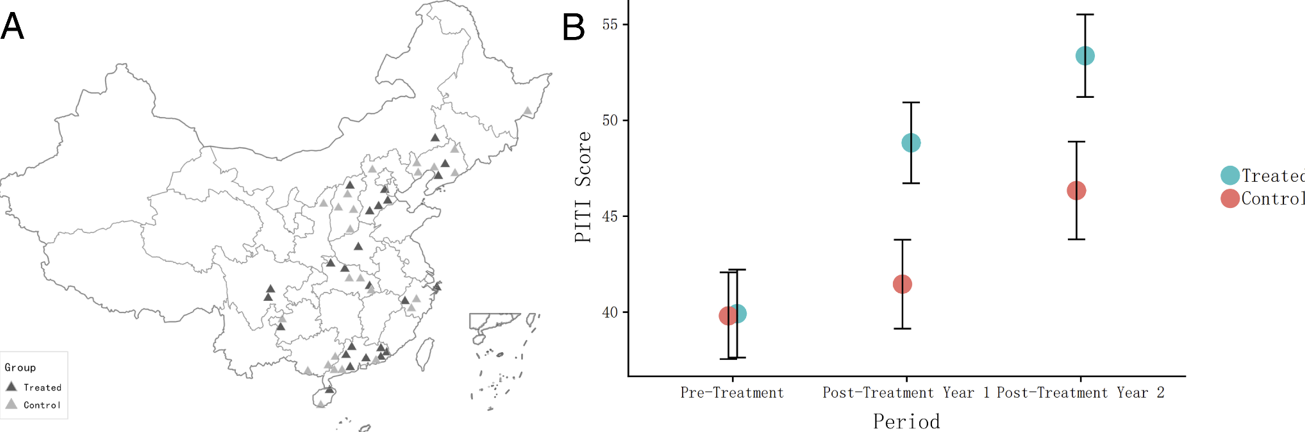

We used a randomised experimental design to increase governmental transparency in cities across China and then compared them to control cities. To do this, we worked with partners at the Institute for Public and Environmental Affair to publicly rate 25 municipal governments in China, using the Pollution Information Transparency Index (PITI). This rating scheme is based on compliance with national rules to disclose information about firm emissions, ambient environmental quality, inspections, and environmental impact assessments, among other topics. The ratings only pertained to whether local governments publicly disclosed the required information, not whether the information indicated good or bad environmental performance. We then compiled the same ratings for 25 control cities but did not disclose them. This intervention significantly increased the amount of environmental information disclosed by treated cities relative to control cities (Anderson et al. 2019). Publicly releasing PITI ratings for treated cities increased transparency by approximately seven points in the first year, which persisted with reinforcement into the second posttreatment year (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pollution Information Transparency Index (PITI) rating for treated and control cities

Increasing transparency improved air quality and reduced pollution violations in China

After successfully increasing transparency in the treated cities, we track the downstream effects on air quality, firm-level emissions, and government enforcement over several years. We find that increased governmental transparency leads to improved regulatory effort by local governments and better environmental outcomes. Specifically, we find that increasing transparency by local governments improved ambient air quality, reduced pollution violations by industrial firms, and enhanced regulatory efforts.

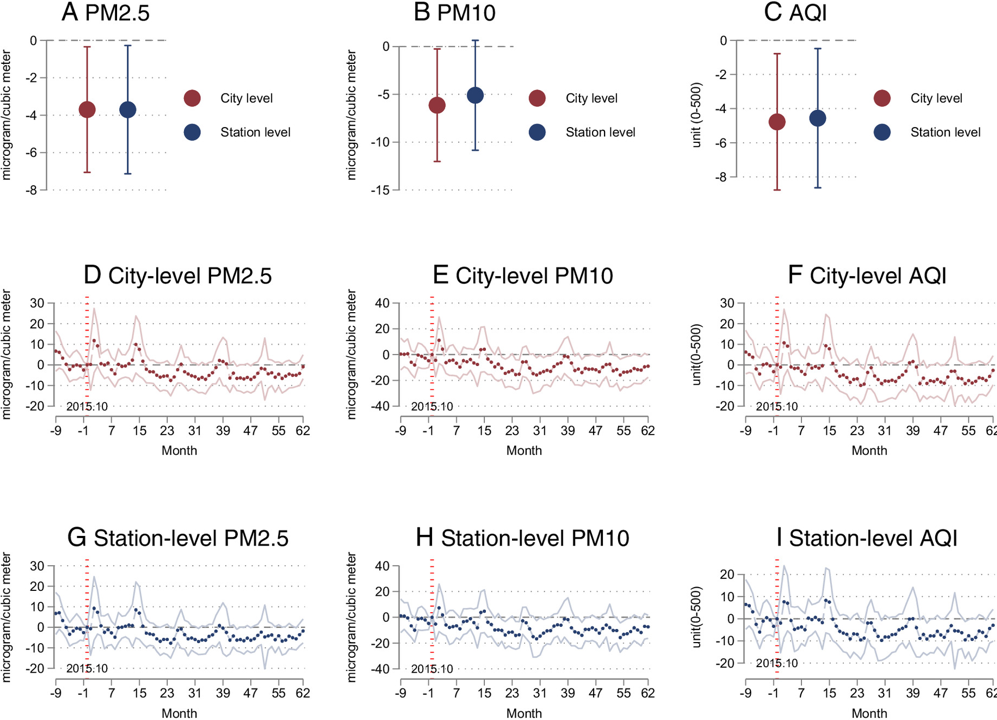

In treated cities that had their transparency randomly boosted, we observed a reduction in ambient air pollution by 8-10% relative to control cities over the next five years. Specifically, we found that, on average, being rated as part of the PITI programme led to a reduction of 3.7 and 6.1 micrograms per cubic meter of urban PM2.5 and PM10, respectively, as well as a 4.8 unit decrease in the air quality index (AQI) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results of rating transparency in treated cities on ambient air quality

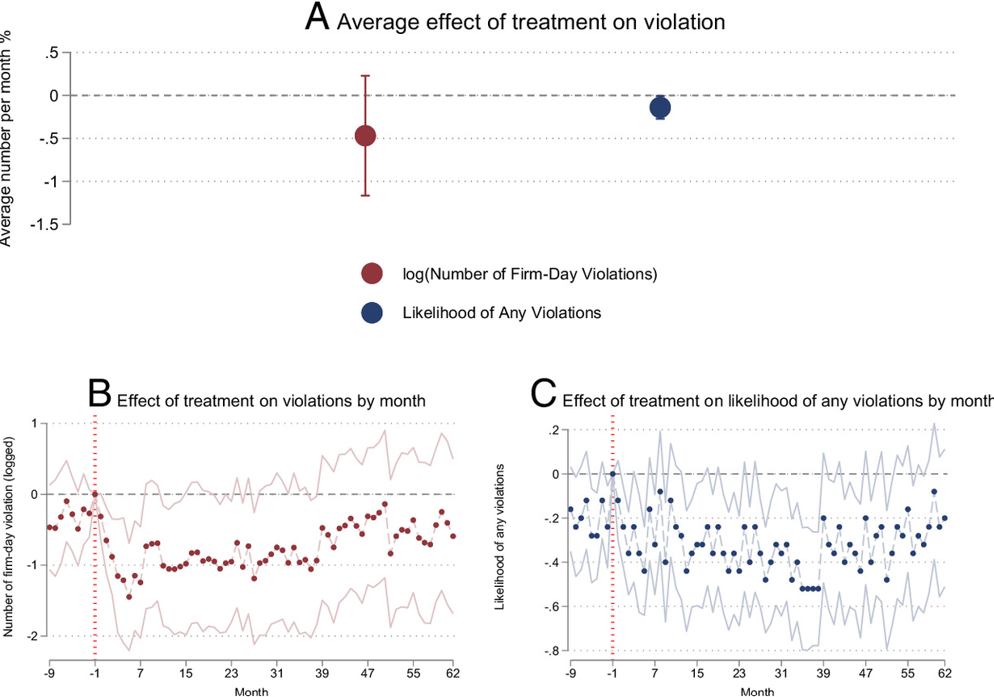

Diving into these results, we looked at industrial firm pollution violations in treated cities. We found that being rated by the PITI programme decreased the count of firm-days with violations of emissions standards by around 37% among all firms, with the effect persisting for five years after treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Results of rating transparency in treated cities on pollution violations

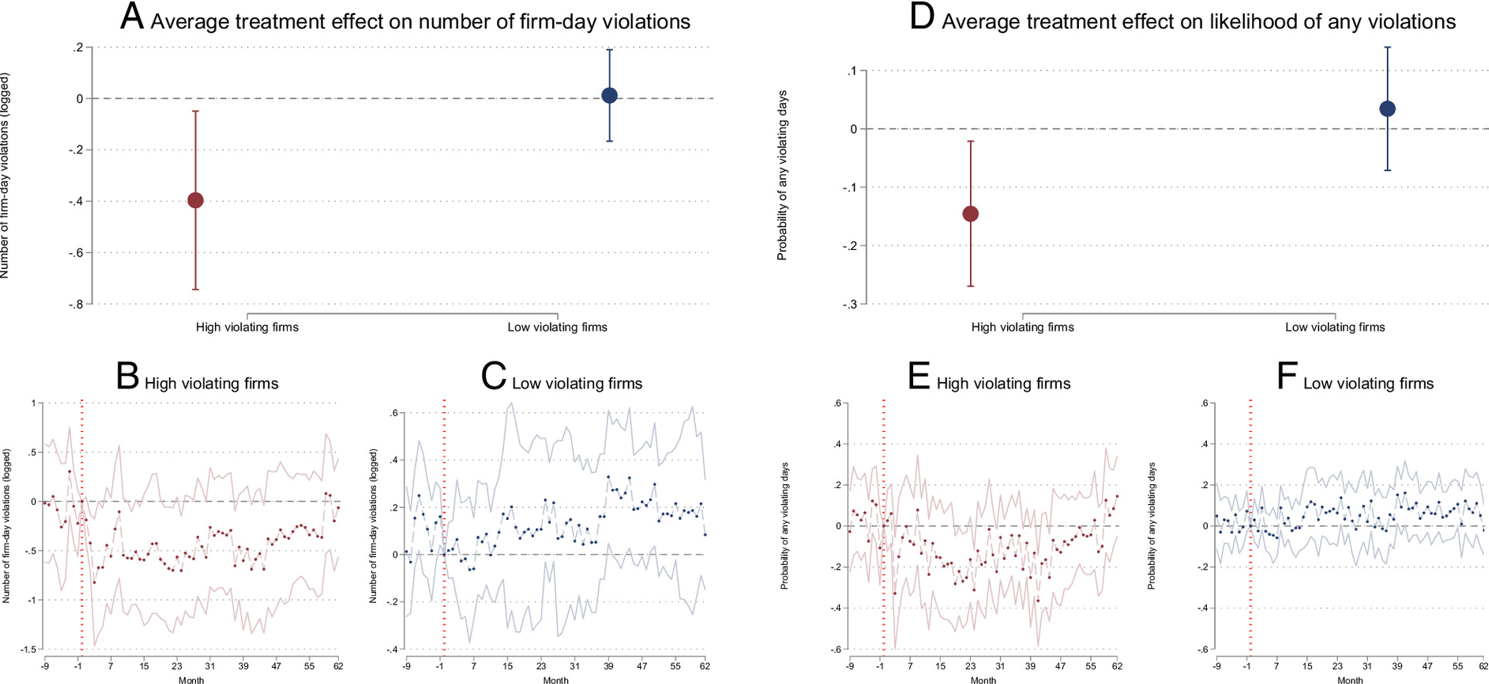

Since they are likely subject to greater scrutiny under transparency, we expect firms with high baseline levels of violations to be the ones to show improvement (Collins et al. 2023). We found that firms in the top 25% of violations in the baseline period reduced violations once transparency improved in the treated cities; additionally, the treatment had little impact on the pollution of firms with a low rate of baseline violations (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Results of rating transparency in treated cities on high and low violating firms

Overall, we found that this decrease in pollution levels would translate to an approximately 0.25% drop in the rate of all-cause mortality (Liu et al. 2019), saving an estimated 24,350 lives annually if it were achieved across China.

How does transparency impact pollution violations?

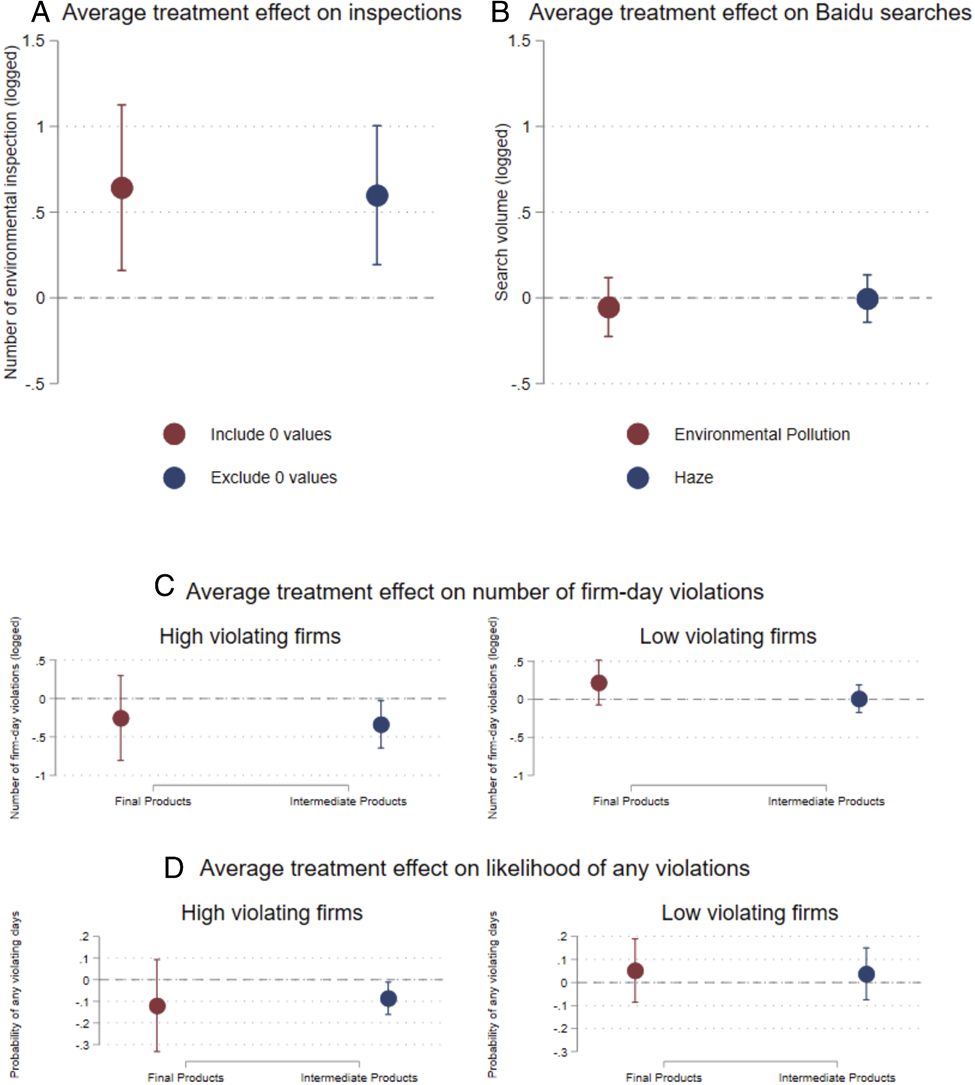

Consistent with the expectation that transparency will increase regulatory stringency by city governments, we found that treated cities had substantially more inspections after the transparency intervention compared to control cities, with regulatory inspections increasing by 90% (Figure 5). Furthermore, we found that there was no change in online searches for ‘environmental pollution’ and ‘haze’ on the Baidu search engine, which is consistent with evidence that citizen and news media attention to pollution and transparency was not higher in treated cities (Anderson et al. 2019). Taken together, these results indicate that firm reductions in emissions are more consistent with governments regulating pollution more stringently following transparency, rather than a direct response by firms to public pressure.

Figure 5. Treatment effect on government inspections and Baidu searches

Establishing causal evidence of transparency improving environmental outcomes

We provide some of the first experimental evidence that increasing governmental transparency improves the management of pollution. By intentionally increasing transparency by city governments using a randomised controlled trial, we show that improving transparency has significantly reduced pollution, likely by improving oversight of firms with a high number of violations. While previous observational studies showed mixed results, this randomised controlled trial found that transparency led to a 37% decline in emissions violations and notable reductions in air pollutants (PM2.5 by 9.6%, PM10 by 9.1%, AQI by 7.6%). While we do not observe the specific means by which firms are adjusting to increased transparency and regulatory effort, related results suggest transparency prompts firms to innovate and patent new ways to produce goods with fewer negative environmental consequences (Zhang et. al 2022). By experimentally manipulating governmental transparency, we rule out the possibility that transparency levels are merely a reflection of existing pollution-control efforts.

Policy failure at implementation is not exclusive to environmental problems or air pollution. Across various sectors, governments often fall short in executing policies as intended. Such lapses in government performance are well documented in health services, education, public finance, and infrastructure, among many other areas. A common diagnosis for these failures is a lack of transparency by government, which leaves the public and other levels of government uninformed and unable to hold governments accountable, allowing politicians and bureaucrats to shirk their responsibilities. Our research provides strong evidence that supports the call for greater transparency by government as a way to improve policy outcomes, at least when the public or other levels of government have the interest and tools to hold governments accountable for policy performance. These results have direct relevance to other countries where regulators actively encourage greater transparency as a way to ensure industry compliance with pollution rules, such as the US, India, Canada, and Indonesia, among others.

(This is reposted from an article originally posted at VoxDev.)

References

Anderson, S E, M T Buntaine, M Liu, and B Zhang (2019), “Non-governmental monitoring of local governments increases compliance with central mandates A national-scale field experiment in China”, American Journal of Political Science, 63(3) 626–643.

Berliner, D (2014), “The political origins of transparency”, Journal of Politics, 76 479–491.

Buntaine, M T et al. (2024), “Does the squeaky wheel get more grease The direct and indirect effects of citizen participation on environmental governance in China”, American Economic Review, 114 815–850.

Collins, M B, S Pulver, D T Hill, and B Manski (2023), “Targeted pollution management can significantly reduce toxic emissions while limiting adverse effects on employment in US manufacturing”, Environmental Science & Policy, 139 157–165.

Dethier, F, C Delcourt, and J Willems (2021), “Transparency of nonprofit organizations An integrative framework and research agenda”, Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 4 e1725.

Dipoppa, G and S Gulzar (2024), “Bureaucrat incentives reduce crop burning and child mortality in South Asia”, Nature, 634 1125–1131.

Duflo, E, M Greenstone, R Pande, and N Ryan (2018), “The value of regulatory discretion Estimates from environmental inspections in India”, Econometrica, 86(6) 2123–2160.

Greenstone, M and B K Jack (2015), “Envirodevonomics A research agenda for an emerging field”, Journal of Economic Literature, 53(1) 5–42.

Gupta, A and M Mason (2014), “Transparency and international environmental politics”, in M M Betsill, K Hochstetler, and D Stevis (eds), Transparency in Global Environmental Governance Critical Perspectives, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 356–380.

Kim, P S, J Halligan, N Cho, C H Oh, and A M Eikenberry (2005), “Toward participatory and transparent governance Report on the sixth global forum on reinventing government”, Public Administration Review, 65(6) 646–654.

Lelieveld, J et al. (2019), “Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116 7192–7197.

Liu, C et al. (2019), “Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities”, New England Journal of Medicine, 381 705–715.

Liu, M, M T Buntaine, S E Anderson, and B Zhang (2025), “Transparency by Chinese cities reduces pollution violations and improves air quality,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(14) e2406761122.

Liu, Mengdi, et al. “Increasing Government Transparency Reduced Pollution Violations and Improved Air Quality in China.” VoxDev, 2 Sept. 2025, https://voxdev.org/topic/energy-environment/increasing-government-transparency-reduced-pollution-violations-and.

Oliva, P (2015), “Environmental regulations and corruption Automobile emissions in Mexico City”, Journal of Political Economy, 123(3) 686–724.

UNECE (n.d.), “Aarhus Convention on access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters”, United Nations Treaty Collection.

Zhang, S, M A Zhang, Y Qiao, X Li, and S Li (2022), “Does improvement of environmental information transparency boost firms’ green innovation Evidence from the air quality monitoring and disclosure program in China”, Journal of Cleaner Production, 357 131921.

Zou, E Y (2021), “Unwatched pollution The effect of intermittent monitoring on air quality”, American Economic Review, 111(6) 2101–2126.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email