Decoding China’s Industrial Policies

Industrial policy is often discussed through high-level narratives and flagship initiatives, yet its implementation—particularly at the subnational level—remains opaque. We leverage large language models (LLMs) to systematically analyze over three million government documents from 2000 to 2022, extracting structured policy information to decode China’s industrial policy at various levels of government. Combining these newly constructed granular industrial policy data with micro-level firm data, we document four sets of facts on China’s industrial policies, including the economic and political rationality of the choice of the target sectors, the dynamics of the policy tools, the diffusion and similarity of policies, and the effects on firm entry and productivity.

Industrial policy is experiencing a powerful resurgence around the world, alongside a revitalized academic interest. Echoing Rodrik (2009), the question is not whether industrial policy should exist, but how it should be practiced: What sectors are targeted? Which tool(s) are used for which industry and in what phase of the industry’s development? How do governments experiment with and learn about the choice of sectors and policy tools? How do governments strike a delicate balance to boost entry and improve productivity while preventing excessive entries and potential overcapacity? What is the role of political incentives in shaping policy choices and outcomes?

Yet empirical work remains constrained by a lack of systematic, large-scale, and granular data. In our recent paper (Fang et al. 2025), we address this gap by building a comprehensive, structured database of industrial policy texts across multilevel government in China, a country that makes extensive use of industrial policies in its sectoral development and technology upgrading. Furthermore, China’s hierarchical government, which blends central guidelines with local discretion, helps shed light on the coordination and diffusion of policymaking and creates rich policy variations ideal for empirical analysis.

Industrial policy is prevalent but unevenly distributed across regions

We begin by constructing a dataset of three million unstructured government policy documents issued between 2000 and 2022. We develop a hallucination-robust LLM pipeline to classify each document as industrial policy or not and extract key information from those identified as such.

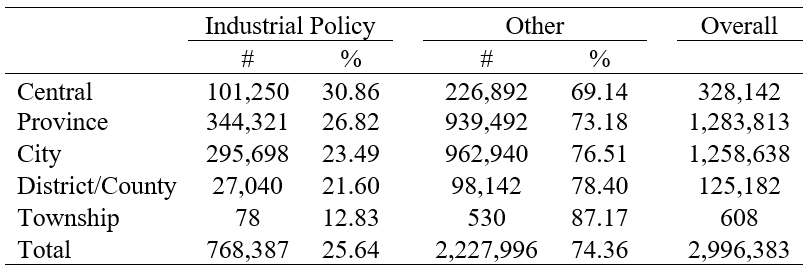

This process identifies 768,387 industrial policy documents—roughly 25% of all government policy texts. As shown in Table 1, most policies are issued by subnational authorities: 13% from the central government, 45% from provincial governments, and 39% from city-level governments. Only a small fraction (3%) come from counties and townships. These figures highlight the decentralized yet active role of local governments in China’s industrial policymaking.

Table 1. Industrial Policies vs. Other Policies, by Government Level

Over time, the volume of industrial policy documents has steadily increased, with a rising share exhibiting a supportive tone. Geographically, policy intensity is higher in more developed regions, suggesting a link between local capacity and policy activity.

Industrial policy is multidimensional

Using LLMs, we extract structured fields from each industrial policy, including the issuing government; a list of targeted industries; policy objectives; policy tone (supportive or regulatory/suppressive); policy tools; measures of policy strength; policy conditionality; references to other governments; citations of other policies; policy dates; measures to monitor, evaluate, and incentivize lower-level governments; measures that grant discretion and promote policy innovation and learning; and local adaptation of policies, among others.

This rich metadata moves us beyond binary definitions of industrial policy. In terms of objectives, promotion of strategic sectors appears in 56% of the documents. Manufacturing and production-related services are frequently targeted (29% and 40%, respectively). While the share of policies targeting manufacturing has slightly declined, within-manufacturing policies increasingly emphasize high-tech and emerging industries, consistent with China’s upgrading agenda.

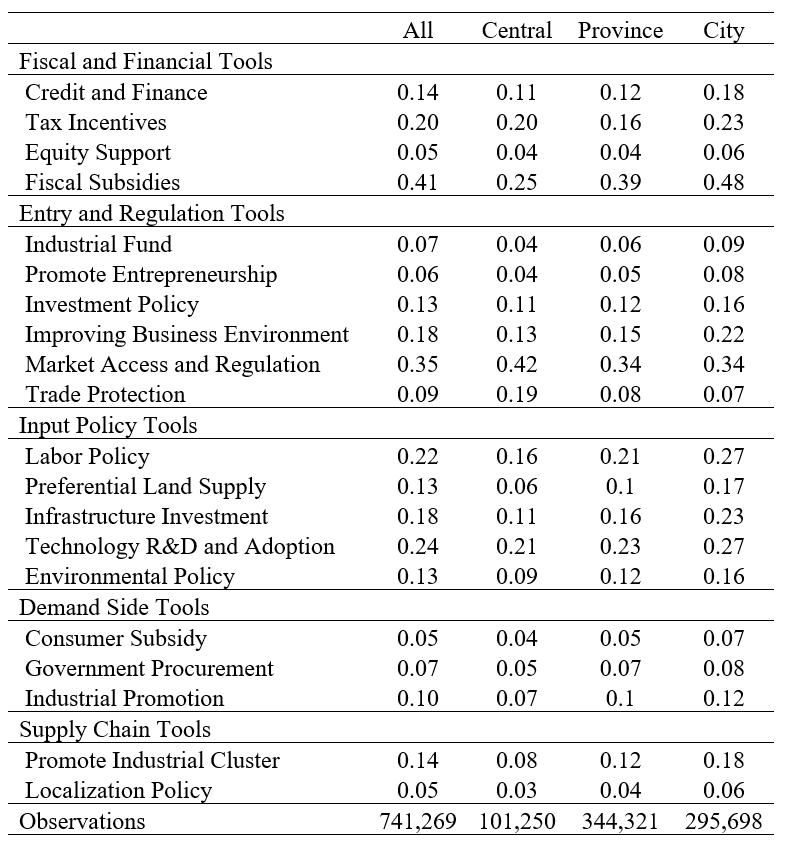

In terms of policy tools, we guide the LLM to classify them into 20 tools. Although fiscal subsidy is the most common policy tool, appearing in 41% of the policies, still more than half of the policies do not employ fiscal subsidy, suggesting the significant bias of existing measures of industrial policy based on the amount of government subsidies. Table 2 shows tool variation across government levels. Local governments favor tools that directly support firms, using fiscal subsidies (48% vs. 25%), labor policies (27% vs. 16%), and infrastructure investment (23% vs. 11%) far more frequently than the central government. In contrast, the central government plays a more strategic and regulatory role, emphasizing tools like market access and regulation (42%) and trade protection (19%), and focusing policy attention on strategic industries (20%).

Table 2. Industrial Policy Implementation Tools, by Government Levels

Industrial policy choices are shaped by local advantage, top-down hierarchy, and local politicians’ career incentives

We examine the drivers of sector selection and find a combination of economic logic, administrative capacity, and political incentives.

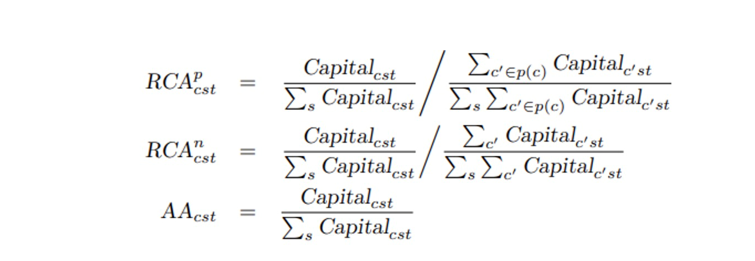

First, we construct measures of a city’s relative advantage from firm registration data based on the cumulative registered capital of firms registered in the city in each industry; two of the measures proxy the city’s revealed comparative advantage (RCA) within the province (with superscript p) and within the entire nation (with superscript n) respectively, and a third measure proxies the city’s absolute advantage (AA). Specifically, for city c (in province p), industry s, and year t, the three measures are constructed as follows:

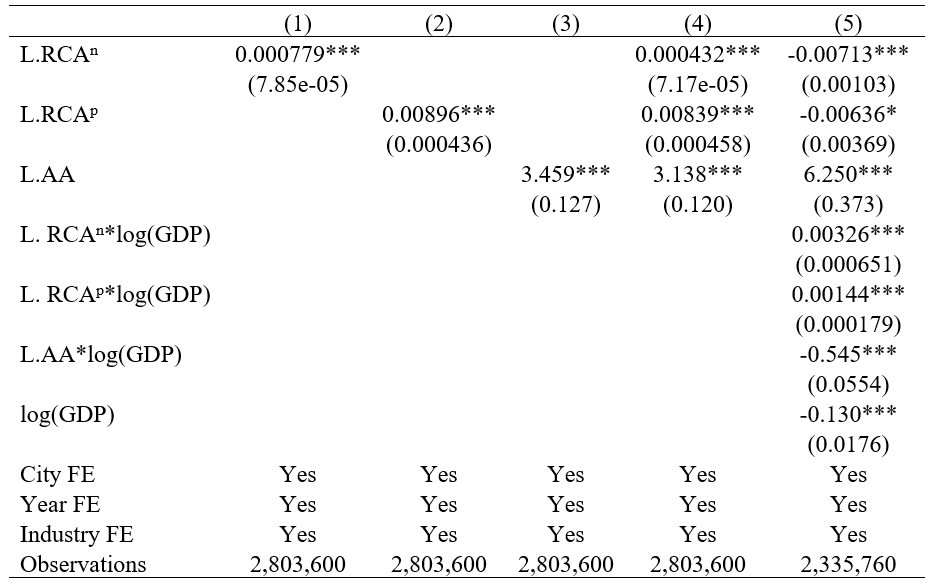

where Capitalcst is the cumulative registered capital in sector s in city c by year t. Cities are more likely to target sectors with higher RCAs, particularly when their fiscal capacity proxied by per capita GDP is high. Table 3 confirms this using a regression framework: both RCAs and AAs positively predict sector targeting (Column 4), but the interaction terms with log(GDP) further show that richer cities are more effective in targeting sectors with RCAs instead of AAs.

Table 3. Sector Choice and Regional Revealed Advantage

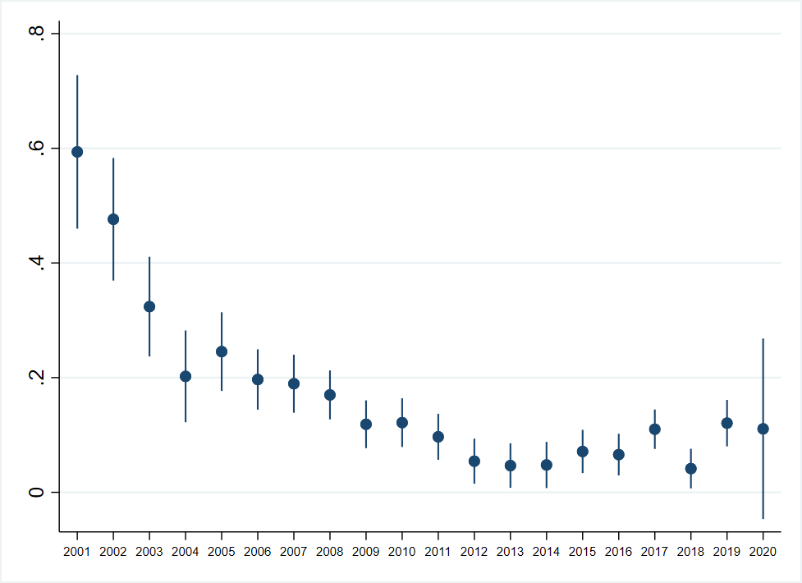

Second, cities tend to follow upper-level governments in sector choices. This top-down policy pass-through is stronger in less developed regions, in jurisdictions with weak ties to higher-level authorities, and when local leaders face stronger political competition. We find that top-down pass-through rates exhibit interesting dynamics. Figure 1 displays the regression coefficients in the sector choice of the city governments on the sector choice of their provincial governments over time, and suggest a turning point around 2013 for an elevated top-down pass-through, which is consistent with a political recentralization in China’s policymaking.

Figure 1. The Dynamics of Policy Pass-through

Finally, policy choices exhibit a certain level of persistence but are sensitive to political turnover. When a local official is replaced, the new leader often shifts the targeted sectors priorities to align with the policies in their previous post, suggesting that politicians’ rotation serves as an important channel for policy diffusion in China.

Industrial policy instruments evolve with the maturity of the targeted industry

Importantly, policy tools often appear in bundles and evolve with industry maturity. To examine this, we regress the indicator for the use of each tool on the number of years that an industry has been targeted in each city. Thus, a positive coefficient indicates an increasing likelihood of tool utilization as the industry matures (more years from the initial target year in the city). As shown in Figure 2, in the early phases of an industry, local governments are more likely to use policy tools that lower entry barriers, such as fiscal subsidies, preferential land supply, market access reforms, and entrepreneurship promotion. As the industry matures, however, the choice of policy tools tends to shift more toward R&D, labor and skills development, supply chain coordination, and consumer-side demand stimulation (e.g., subsidies, trade fairs, government procurement).

Figure 2. Within-industry Change in Policy Tool and Implementation Method

As policy diffuses across the cities, local protectionism rises and policy effectiveness declines

To evaluate the policy effectiveness, we match industrial policy exposure with firm-level outcomes. On average, firms in targeted sectors enjoy monetary benefits, including more subsidies, higher tax deductions, and better access to finance. These translate into higher firm entry rates, and a positive but short-lived association with firm productivity.

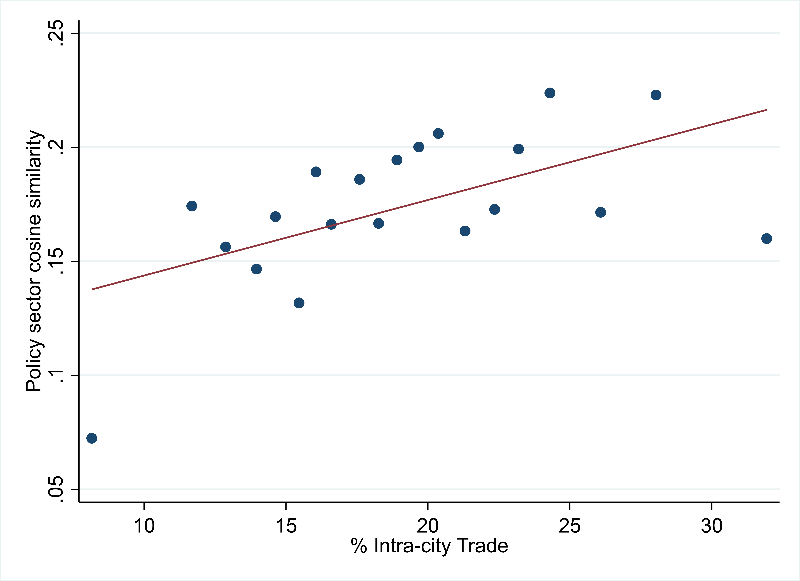

Figure 3. Policy Sector Similarity and Local Protectionism

Yet imitation has costs. Our analysis shows that cities in China often adopt similar industrial policies—especially cities within the same province—leading to duplication, inefficient competition, and overcapacity. This policy overlap, measured by the cosine similarity of the policy vectors between each city pair, is linked to growing local protectionism: firms trade more with other firms within the city, as shown in Figure 3.

We also provide empirical evidence that imitating the sectors supported by pioneering cities is often ineffective or even counterproductive. Further examining the mechanism behind the ineffectiveness of policy diffusion, we find that as policies diffuse across regions, policy followers are less savvy in the choices of the target industry, the policy tools, and the implementation methods, and are more likely to follow the upper-level governments’ practices.

This suggests that industrial policy is a far more complex matter than just copying successful models—it requires careful adaptation to local conditions, including local administrative and fiscal capacity. In addition, it highlights the challenges in coordinating policies to, on the one hand, incentivize local governments to boost entries to a target sector, and on the other hand, to avoid protectionism and overcapacity from overly similar policies and excessive entries.

Conclusion

Our study provides the first large-scale, structured, and granular portrait of industrial policy practice across all levels of China’s government. Using LLMs to decode policy documents, we uncover how sector choices, toolkits, and policy dynamics are shaped by local economic fundamentals, administrative capacity, and political incentives.

The findings underscore that industrial policy is neither monolithic nor static. Its effectiveness depends critically on implementation detail, regional context, and the ability of local governments to adapt rather than simply copy. For researchers and policymakers alike, understanding how industrial policy works on the ground is crucial to assessing its true potential.

References

Fang, Hanming, Ming Li, and Guangli Lu. 2025. “Decoding China's Industrial Policies.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 33814. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33814.

Rodrik, Dani. 2009. “Industrial Policy: Don’t Ask Why, Ask How.” Middle East Development Journal 1 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793812009000024.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email