Excessive Issuance of New Funds in China and Implications for Investor Protection

The Chinese mutual fund industry is only one-tenth the size of its US counterpart, but the number of funds in China has surpassed that of the US. Our study shows that such a large number of funds is unhealthy: managers issue new funds repetitively with different custodian banks, resulting in the average manager overseeing 2.7 funds. Managers shift profits to new funds in order to attract more flows. Among funds under the same manager, new funds have higher returns than old funds, spurring concerns over investor protection.

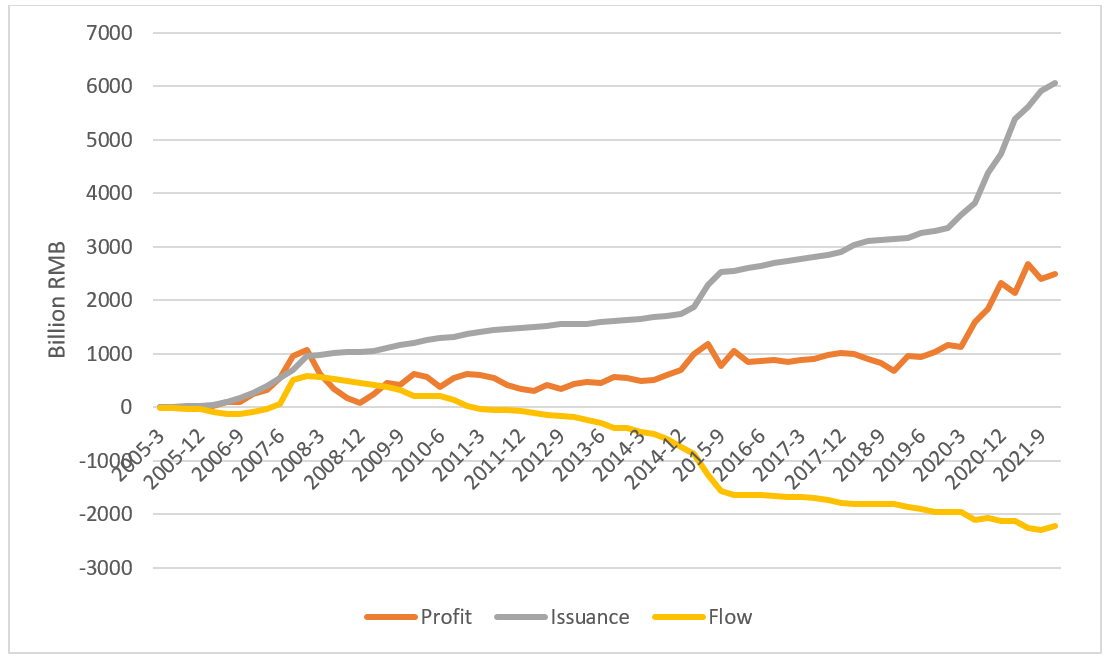

At the end of 2021, Chinese mutual fund managers collectively managed 25 trillion yuan across more than 9,288 funds. While the assets under management (AUM) in China totaled just one-tenth of those in the US mutual fund industry (34 trillion USD), the number of funds in China surpassed the number in the US (8,840). Mutual funds in the US grow by attracting flow into existing funds, but flow to existing funds is negative in China. Instead, Chinese mutual fund growth is primarily driven by new fund issuances. In this study, we focus on active equity mutual funds in China. Figure 1 plots cumulative cash flow to these funds under three channels: profit, new issuance, and flow to existing funds. We can see that profit and flow add up to approximately zero, while new issuance contributes roughly 100% of the current AUM in the industry.

Figure 1. Cumulative Cash Flow to Equity Mutual Funds in China

Why do Chinese mutual fund companies issue so many funds? Does the large number of available funds increase investors’ welfare? We find that most of the new funds are repetitive, with 89% of them managed by existing managers who hold stocks similar to the old funds. Managers issue new funds at different banks in exchange for their support in raising money. In China, managers oversee 2.7 funds on average; in contrast, US fund managers oversee an average of 1.3 funds.

We find that the key factor in the excessive fund issuances in China is the high custodian fee charged by banks, which stands at 0.25% per year. Banks, the primary sales channel for mutual funds in China, exert significant influence over fund distribution. When they sell mutual funds to investors, they earn front load, which is equal to 1.5%. If a fund is under the bank’s custody, the bank also earns a custodian fee of 0.25 % per year. The custodian fee may seem trivial, but it is highly attractive to banks for two reasons. First, once a fund is issued, the custodian bank cannot be changed, so the income is stable and has virtually no marginal costs. Moreover, if some fund shares are sold through other channels or the fund grows, the fee may grow larger in the future. We estimate the present value of all future custodian fee income to be 5.79%, much higher than the front load. Therefore, banks allocate almost all sales effort to funds under their custody.

Why do banks pressure mutual fund companies to issue new funds rather than help them sell old funds? We find that banks face a prisoner’s dilemma. If a star manager issues a new fund, some of the investors from the old funds will redeem and move their money to the new fund. Therefore, with limited sales capacity, a bank’s optimal strategy is to poach star managers whose funds were placed under custody of other banks, and ask the manager to issue a new fund at the new bank, thereby siphoning investors from the other banks. For example, when Gesong Liu achieved the highest return among all managers in 2019, he issued three new funds in 2020 which were under the custody of three different banks. Such competition is destructive because every bank is forced to endlessly issue new funds. Otherwise, they will lose investors from funds under their custody, and face the loss of custodian fee income.

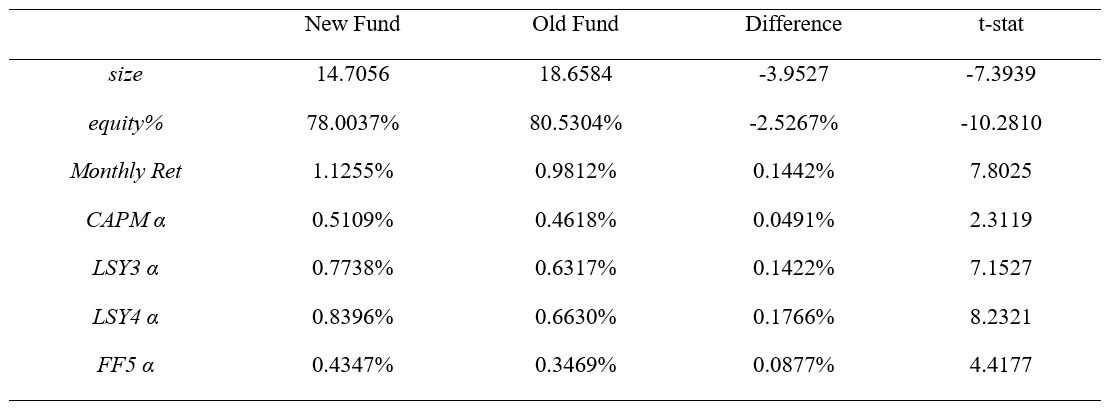

This distorted incentive structure has led to excessive fund issuance, with managers overseeing multiple funds. This creates a problem of managerial favoritism. We find that managers tend to favor new funds, which outperform older funds by an average of 1.5% to 2% per year (Table 1). This differential treatment is economically large. In our sample period (2005–2021), mutual funds generated 6% alpha per year on average. Managers who oversee multiple funds shift one-third of the excess return to new funds. The result is robust under different risk-adjusted models. This result is also not driven by different fund sizes or cash holdings. Using a staggered difference-in-differences (DID) approach, we show that when a fund manager issues a new fund, the performance of older funds declines significantly.

Table 1. The Return of New Funds and Old Funds Managed by the Same Manager

The preference for new funds can be explained by the convex flow-return relationship exhibited by investors (Chevalier and Ellison 1997). Consider a manager who can generate a 10% return per year. He can distribute the return evenly across two funds or allocate it asymmetrically, e.g., 15% for one fund and 5% for another. The convex flow-return relationship suggests that the latter attracts more inflows. Furthermore, using kernel regression, we find that investors are more sensitive to high returns in new funds. There are two reasons. First, when investors make Bayesian updates on managers’ skills, a new fund has a shorter history, so a new datapoint of return carries higher weight. Second, for old funds, many investors are at a paper loss. When the fund earns a positive return in the next period, some of the paper losses will be eliminated, making these investors eager to sell. Thus, the total inflow is dampened for an old fund with good performance. Given that investors’ flow is more sensitive to returns in new funds, managers’ optimal strategy is to shift profits to new funds.

As to how managers shift returns, our analysis identifies front-running as a potential channel. That is, when a manager intends to buy a stock, they buy with the new fund first. This way, the buying trades of new funds occur at lower prices. After the new fund has finished buying, the manager will buy with old funds at higher prices. Empirically, we find that the holding position changes of new funds predict that of old funds in subsequent periods, but not vice versa. This suggests that trades in the same direction occur first in new funds, giving them more favorable prices and higher overall returns.

These findings have important regulatory implications for the Chinese mutual fund industry and investor protection. Excessive fund issuances, driven by high custodian fees, result in unfair treatment of investors and distorted market dynamics. We recommend that Chinese regulators marketize the custodian market to foster competition and reduce custodian fees. For context, the average custodian fee in the US was 0.025% in 1997 (Cullinan and Bline 2005), a mere one-tenth of the custodian fee in China in 2021. In addition, fund companies should set incentives that reward long-term performance to curb the myopic behaviors of managers. Mutual fund companies should also work with sales channels to educate investors to cultivate patient capital.

References

Chevalier, Judith, and Glenn Ellison. 1997. “Risk Taking by Mutual Funds as A Response to Incentives.” Journal of Political Economy 105 (6): 1167–1200. https://doi.org/10.1086/516389.

Cullinan, Charles P., and Dennis M. Bline. 2005. “An Analysis of Mutual Fund Custodial Fees.” Journal of Applied Business Research 21 (1). https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v21i1.1496.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email