Place Prosperity vs People Prosperity: Migration and the Intergenerational Transmission of Knowledge

The trajectory of an economy's development can often be better understood through the historical experiences of its populace. Long before the availability of comprehensive official data, Chinese family genealogies are a valuable resource for reconstructing economic evolution over time, as the following shows.

For decades, researchers have debated whether it is more important to focus on the prosperity of places or of people (Winnick 1966; Glaeser 2005). Some aspects of the question are straightforward. Most importantly, it is the well-being of people—not places—that matters in economic welfare analysis, since geographic locations themselves have no intrinsic value (von Neumann Whitman 1972). The distinction between place and people becomes meaningful only when migration occurs—without it, the economic trajectory of a place would mirror that of its residents. Nevertheless, despite the complications migration introduces for targeting policy, many interventions continue to be framed in terms of geography—so-called “place-based policies” (Kline and Moretti 2014)—in part because geographic locations, rather than individuals, often serve as more practical units for redistribution (Austin, Glaeser, and Summers 2018).

There is much to gain from integrating the perspectives of people-based and place-based analyses, and recent studies have started to bridge this gap. For instance, Autor, Dorn, Hanson, Jones, and Setzler (2025), following an approach by Dustmann, Otten, Schoenberg, and Stuhler (2023), examine how U.S. labor markets adjusted to increasing Chinese import competition, using two decades of data that captures both geographic units (commuting zones) and individual workers. If relatively small disruptions—like parental job loss—can negatively affect the next generation’s well-being (Oreopoulos, Page, and Stevens 2008), then larger historical shocks, such as the Black Death or colonial rule, are likely to have even more enduring effects, persisting across multiple generations (see Pamuk 2007 and Dell 2010, respectively).

To investigate long-term impacts from both geographic and generational perspectives—before the availability of official intergenerational data—Shiue and Keller (2024) use Chinese family genealogies to examine how the fall of the Ming dynasty affected elite behavior in Central China. The transition from the Ming (1368–1644) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) is widely considered one of the deadliest civil conflicts in history, leading to the death of roughly 16% of China’s population and causing extraordinary devastation in Tongcheng county, Anhui province—the region at the center of their study.

Chinese genealogies are privately maintained family records, typically organized in the form of a pedigree chart. While these records are rooted in the cultural importance of ancestor worship, they have also historically played significant economic roles—supporting the allocation of property rights, tax administration, and the provision of public goods. Estimates suggest that between 50,000 and 100,000 such genealogies still exist today. Though their level of detail and completeness varies (Telford 1986), the seven genealogies analyzed by Shiue and Keller (2024) contain not only standard demographic data—such as dates of birth and death, marriages, and number of children—but also information on social status, residence, and burial location.

Shiue and Keller (2024) leverage geographic variation in exposure to the Ming dynasty’s collapse by comparing regions that experienced severe destruction with those that were less affected, using mortality data from the decade of most intense violence (1634–1644). Their analysis traces the long-term effects of this historical shock over five generations, covering a time span of 300 years.

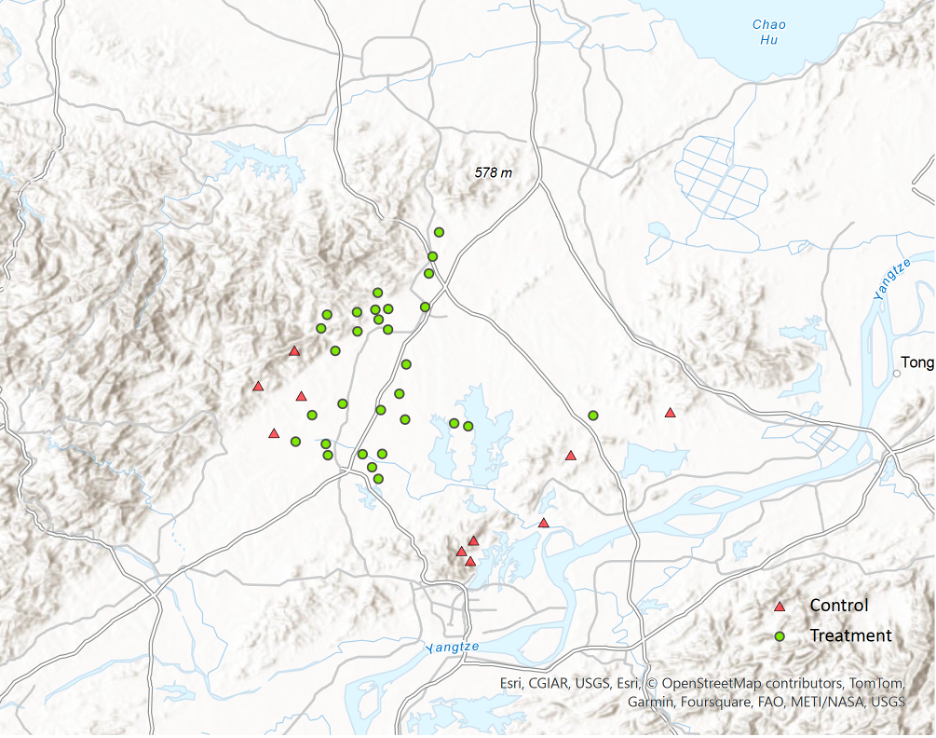

Figure 1. Treatment versus Control Places in Tongcheng County

Figure 1 indicates that exposure to the Ming shock was more limited in relatively peripheral and mountainous areas.

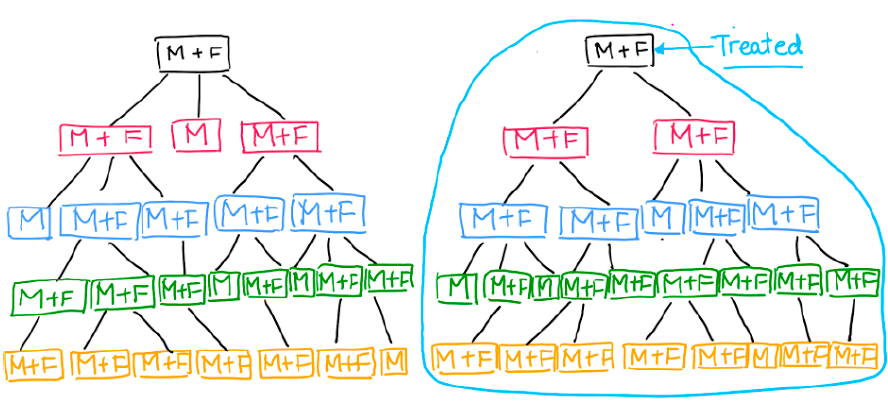

The treatment assignment for couples who lived during the Ming-Qing transition is extended to all their respective descendants in the following four generations. This is shown in Figure 2, with treated five-generation family lines on the right and control family lines on the left.

Figure 2. Treatment of People over Five Generations

The key outcome variable in Shiue and Keller’s (2024) analysis is elite status, defined by participation in China’s civil service examination system (keju), a highly competitive, tournament-style selection process.1 Drawing on data from two generations prior to the Ming collapse, they show that elite families were distributed in roughly equal proportions across both treatment and control areas.

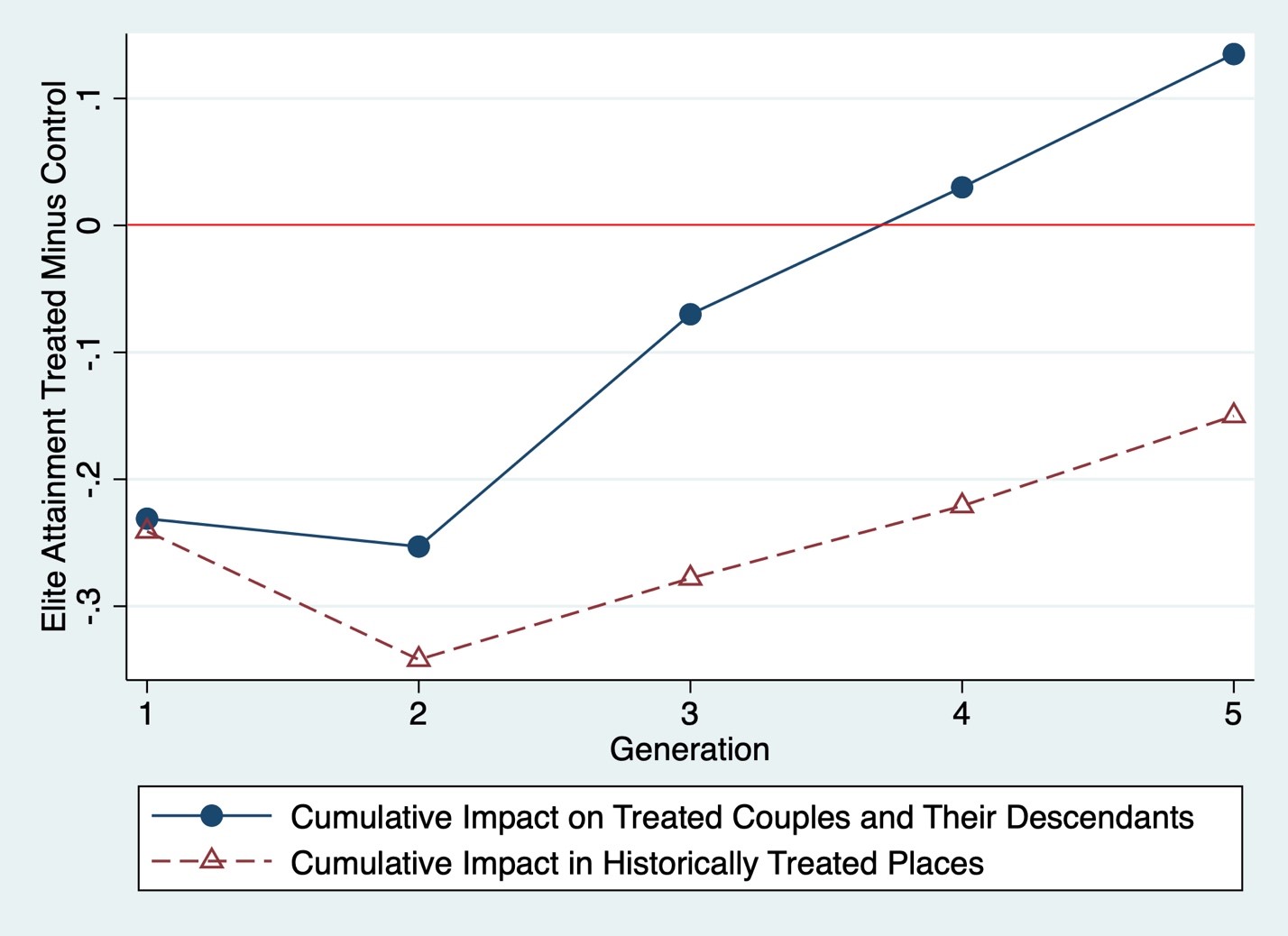

Using a sample of approximately 1,600 distinct family lines tracked across five post-shock generations, Shiue and Keller (2024) employ least squares regressions to demonstrate that residing in a village heavily affected by the fall of the Ming significantly reduced the likelihood of attaining elite status. This finding is consistent with the idea that disruptions—including civil war violence, local peasant uprisings, and famine—would have hindered educational preparation in more exposed places. Yet, their results also reveal a reversal over time: in generations three through five, descendants of families from exposed areas are more likely to achieve elite status than those from less affected regions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Treatment of People versus Treatment of Places

Figure 3 presents the cumulative treatment effect on individuals, measured at the level of family lines (as defined in Figure 2). The upward slope from generations three to five indicates that descendants of families exposed to the fall of the Ming achieved elite status at higher rates than those in the control group. By the fourth generation, the typical treated family line had not only recovered from the initial loss experienced by its first-generation ancestors but had surpassed it. This pattern reflects a clear reversal of fortunes in elite attainment when the analysis is conducted at the individual, or people-based, level.

Shiue and Keller (2024) contrast this treatment of people with the difference in elite attainment in historically treated versus control places in each generation for the exact same sample. They refer to the latter, shown cumulatively as the lower dashed line in Figure 3, as treatment of places. It is equal to the average elite attainment difference in the green circle villages and the red triangle villages shown in Figure 1.2

While the treatment effects on people and places align in the first generation, Figure 3 reveals that their trajectories diverge in subsequent generations. This distinction underscores the importance of analytical perspective: whether one examines the long-run adjustment of geographic locations or of the individuals living through the historical shock can yield qualitatively different conclusions. Notably, the treatment of places does not exhibit a reversal of fortunes in elite attainment—even by the fifth generation—whereas the treatment of people does. In this context, individuals appear more resilient than the places they inhabit.

The divergence between the treatment of people and the treatment of places, as shown in Figure 3, is driven by migration—that is, the movement of individuals across geographic locations. Specifically, some family lines initially exposed to the shock in the first generation had relocated by the second generation to villages that had not experienced the same level of destruction. To fully understand why patterns of prosperity differ between people and places, it is essential to examine how migrants differ from the populations that remained in their original locations.

Shiue and Keller (2024) report that just over 3% of treated family lines—46 out of all those treated—migrate to non-exposed locations by the second generation. Migration rates for this historical era tend to be low, and the transition from the Ming to the Qing might have temporarily increased migration costs further.

Importantly, the treated families who do migrate differ systematically from those who remain in shock-exposed villages. First, migrant families tend to be younger: on average, men in out-migrating lines are 10 years younger, and women 8 years younger, than their counterparts in families that stayed. Second, these migrating families were more affluent in the first generation. They were more likely to include individuals with elite status, to have a higher number of sons, and to display other indicators of socio-economic advantage. These patterns are consistent with broader findings on the determinants of migration, where younger and wealthier individuals are more likely to move.

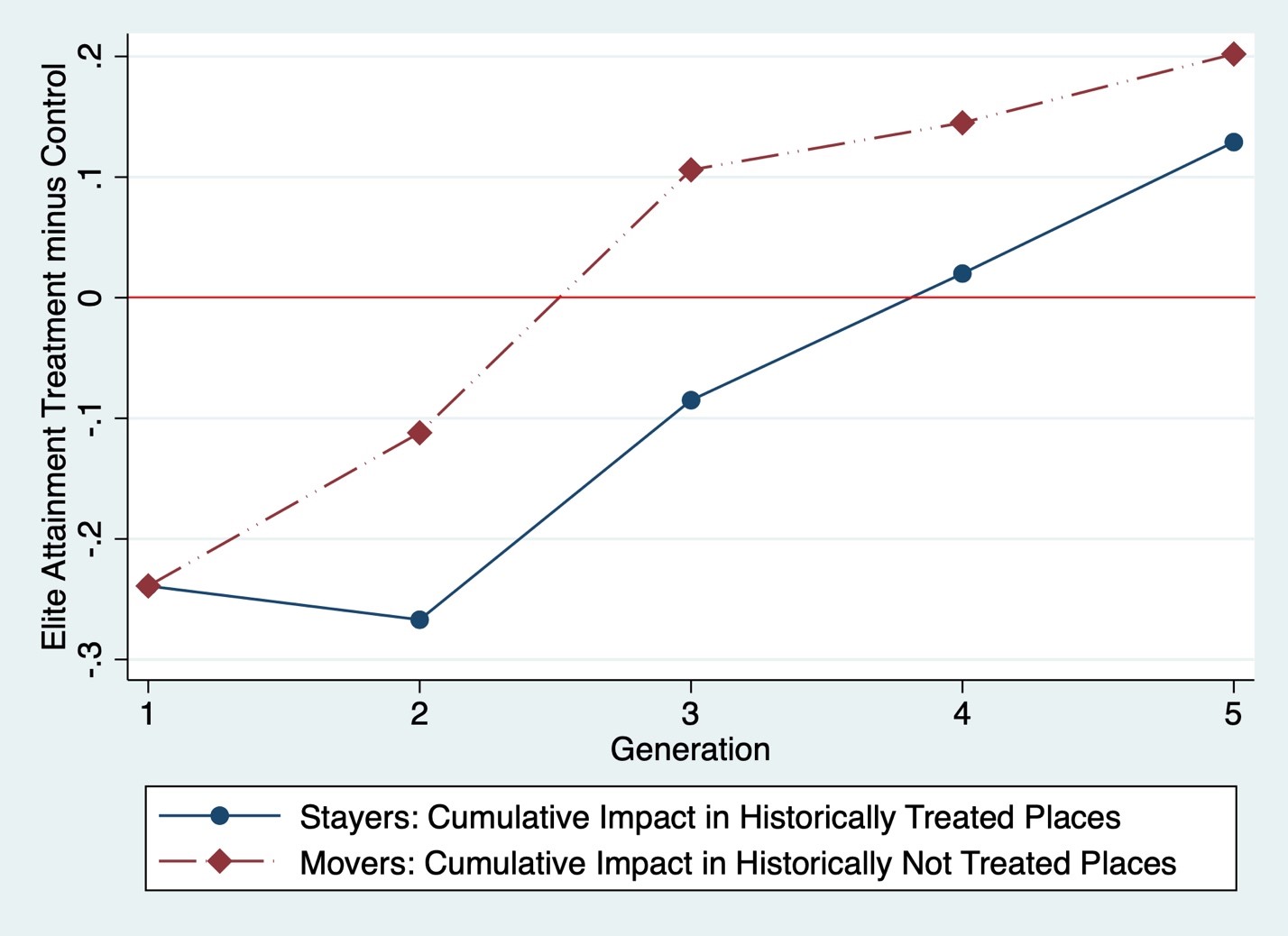

In this context, migrants are positively selected—a key factor underlying the divergence between the treatment-of-people and treatment-of-place effects shown in Figure 3. To explore this distinction more systematically, Shiue and Keller (2024) perform separate regression analyses for two subsets of treated family lines: those who, in the current generation, continue to reside in historically exposed locations (“Stayers”), and those who have relocated to historically non-exposed areas (“Movers”). Figure 4 compares elite attainment across these two groups, highlighting how migration reshapes long-run outcomes.

The results for Stayers in Figure 4 closely resemble the treatment-of-people estimates presented in Figure 3, which is consistent with the relatively limited migration between historically exposed and non-exposed areas. However, among those treated family lines that do relocate, elite attainment tends to be higher than for those who remain in shock-exposed villages. This difference is particularly pronounced in the second generation. As shown in Figure 4, family lines that migrate recover from the first-generation loss more rapidly—achieving full recovery by the third generation, whereas those who remain in historically exposed locations do not reach similar levels of elite attainment until the fourth generation.

Figure 4. Treated Family Lines that Move versus Treated Family Lines that Stay

Another important factor behind the reversal in elite attainment observed in Figure 3, according to Shiue and Keller (2024), is a shift in values among treated family lines following the shock. Specifically, families exposed to the fall-of-Ming destruction appear to have placed greater emphasis on socially acceptable behavior, distancing themselves from the kinds of tax evasion and corruption that had contributed to local uprisings against elites during the broader context of Ming-Qing warfare in Tongcheng. In this setting, a renewed focus on the civil service examination was a natural response, given the high social prestige accorded to its successful candidates.

Couples who lived through the shock in exposed villages likely experienced intense violence and hardship firsthand, shaping their worldviews and responses to instability. Shiue and Keller (2024) provide evidence that these experiences were transmitted more strongly across generations in treated family lines than in control family lines.

In particular, they find that the degree of intergenerational persistence in elite attainment is significantly higher among treated families after the fall of the Ming—but not prior to it. This persistence is especially pronounced in family lines where both parents and their sons had overlapping lifespans, allowing for extended face-to-face interaction and direct transmission of values and knowledge.

A limitation of Shiue and Keller’s (2024) analysis is that it relies on a sample rather than a comprehensive census of all individuals and locations in this region of China. Furthermore, their study follows a cohort-based design, with no new entrants added over time. As a result, the representativeness of the sample diminishes over the long horizon of the study; the economic conditions of Tongcheng in the 1800s are likely captured less accurately than those of the 1600s.3

Recent research has begun to integrate people-based and place-based perspectives in the context of advanced economies such as the United States (see also Bloom, Handley, Kurman, and Luck 2024; Pierce, Schott, and Tello-Trillo 2024). These studies typically concentrate on the recent past and are limited to within-generation analyses. A promising avenue for extending the temporal scope of such work is intergenerational linking across historical censuses, which can help construct long-horizon “people” datasets for some countries dating back to the 1800s. However, these datasets also face limitations: despite their size, they are not fully representative, and even with the addition of crowd-sourced genealogical data, low linkage rates remain a significant challenge.4

In sum, integrating people- and place-based perspectives offers valuable insight into the long-run processes of economic development. Take the Ruhr region in western Germany, a long-established industrial center. Its emergence was closely tied to natural resource endowments—particularly coal—with mining beginning in the early 19th century. However, the region’s full trajectory—its industrial expansion, prolonged growth, eventual decline, and future potential for structural transformation—cannot be fully understood without considering the role of individuals and families. The intergenerational transmission of occupations—“coal miner, like father, like son”—highlights how economic identities are deeply rooted in social and familial, that is, people-based, networks.

1 While succeeding in the keju often led to great wealth, being merely a rich merchant or large landowner was not enough to be part of the elite. Also, consistent with historical accounts Shiue and Keller (2024) include men who studied for the keju in the definition of elite

2 Figure 1 shows only the treatment and control places of first-generation men; however, because in future generations men live also in other villages of the area, this does not give the full picture.

3 Shiue and Keller (2024) discuss the influence of intergenerational linking on sample composition.

4 Bailey, Cole, Henderson, and Massey (2020) highlight concerns regarding the representativeness of linked historical data. Linkage rates across historical U.S. censuses—when supplemented with genealogical information from FamilySearch.org—are estimated at approximately 50% (Buckles, Price, Ward, and Wilbert 2024). Assuming a constant intergenerational link rate of 0.5, the proportion of the original sample retained over five generations would decline to just over 6% (0.5⁴ = 0.0625), underscoring the challenges of constructing long-run representative panel data in this way.

References

Austin, B., E. L. Glaeser, and L. H. Summers (2018), “Jobs for the Heartland: Place-based policies in the 21st century America”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 151-232.

Autor, David, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, Maggie R. Jones, and Bradley Setzler (2025), “Places versus People: The Ins and Outs of Labor Market Adjustment to Globalization”, NBER # 33424.

Bailey, Martha, Connor Cole, Morgan Henderson, and Catherine Massey (2020), “How Well Do Automated Methods Linking Perform? Evidence from the LIFE-M Project”, Journal of Economic Literature 58 (4):997-1044..

Bloom, N., K. Handley, A. Kurman, and P. Luck (2024), “The China Shock Revisited: Job Reallocation and Industry Switching”, Stanford University.

Buckles, K., J. Price, Z. Ward, and H. E. B. Wilbert (2024), “Family Trees and Falling Apples: Historical Intergenerational Mobility Estimates for Women and Men”, NBER # 31918.

Dell, Melissa (2010), “The Persistent Effects of Peru’s Mining Mita”, Econometrica Vol. 78, No. 6, 1863–1903.

Dustmann, Christian, Sebastian Otten, Uta Schoenberg, and Jan Stuhler (2023), “The Effects of Immigration on Places and Individuals – Identification and Interpretation”, UCL working paper.

Glaeser, Edward L. (2005), “Should the Government Rebuild New Orleans, or Just Give Residents Checks?”, The Economist’s Voice, Vol. 2, Issue 4.

Kline, Patrick, and Enrico Moretti (2014), “People, Places, and Public Policy. Some Simple Welfare Economics of Local Economic Development Programs”, Annual Review of Economics 6(1): 629-662.

Von Neumann Whitman, Marina (1972), “Place Prosperity and People Prosperity: The Delineation of Optimum Policy Areas.” In Mark Perlman et al. (eds.), Spatial, Regional and Population Economics: Essays in Honor of Edgar M. Hoover. New York: Gordon and Breach, pp. 359–393.

Oreopoulos, P., M. Page, and A. Stevens (2009), “The Intergenerational Effects of Worker Displacement”, Journal of Labor Economics Vol. 26(3).

Pamuk, S. (2007), “The Black Death and the origins of the ‘Great Divergence’ across Europe, 1300–1600”, European Review of Economic History 11, 289–317.

Pierce, J. R., P. Schott, and C Tello-Trillo 2024), “To Find Relative Earnings Gains after the China Shock, Look Outside Manufacturing and Upstream”, NBER working paper # 32438.

Shiue, Carol H., and Wolfgang Keller (2024), “Elite Strategies for Big Shocks: The Case of the Fall of the Ming”, NBER working paper # 33121.

Telford, Ted A. (1986), “Survey of Social Demographic Data in Chinese Genealogies”, Late Imperial China Vol. 7(2), pp. 118-148.

Winnick, L. (1966), “Place prosperity vs. people prosperity: Welfare considerations in the geographic redistribution of economic activity”, Real Estate Research Program, UCLA, Essays in Urban Land Economics in Honor of the Sixty-Fifth Birthday of Leo Grebler, 273–283.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email