Banking and Banking Reforms in China in a Model of Costly State Verification

We present a macro view of China’s financial system, in which a monopolistic banking sector coexists endogenously with bonds and private loans. In equilibrium smaller firms raise finance from private lending, larger firms do so through bank loans, and the largest firms do so by issuing bonds. The model predicts that expanding credit supply increases bank loans but reduces bond finance and private lending, in absolute terms and relative to total credit. In addition, removing the interest rate ceiling on bank lending—a recent reform in China—induces larger loans and higher lending rates, lowering the share of bank loans in total credit. We present empirical evidence to support these predictions.

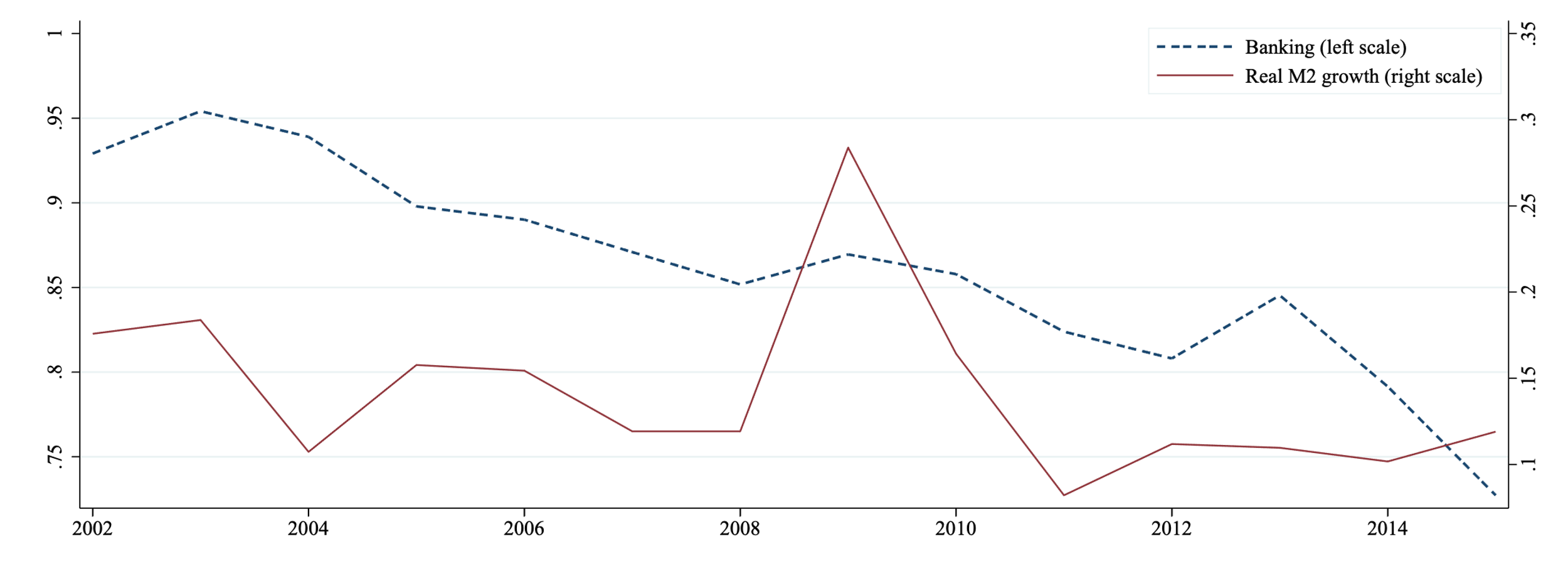

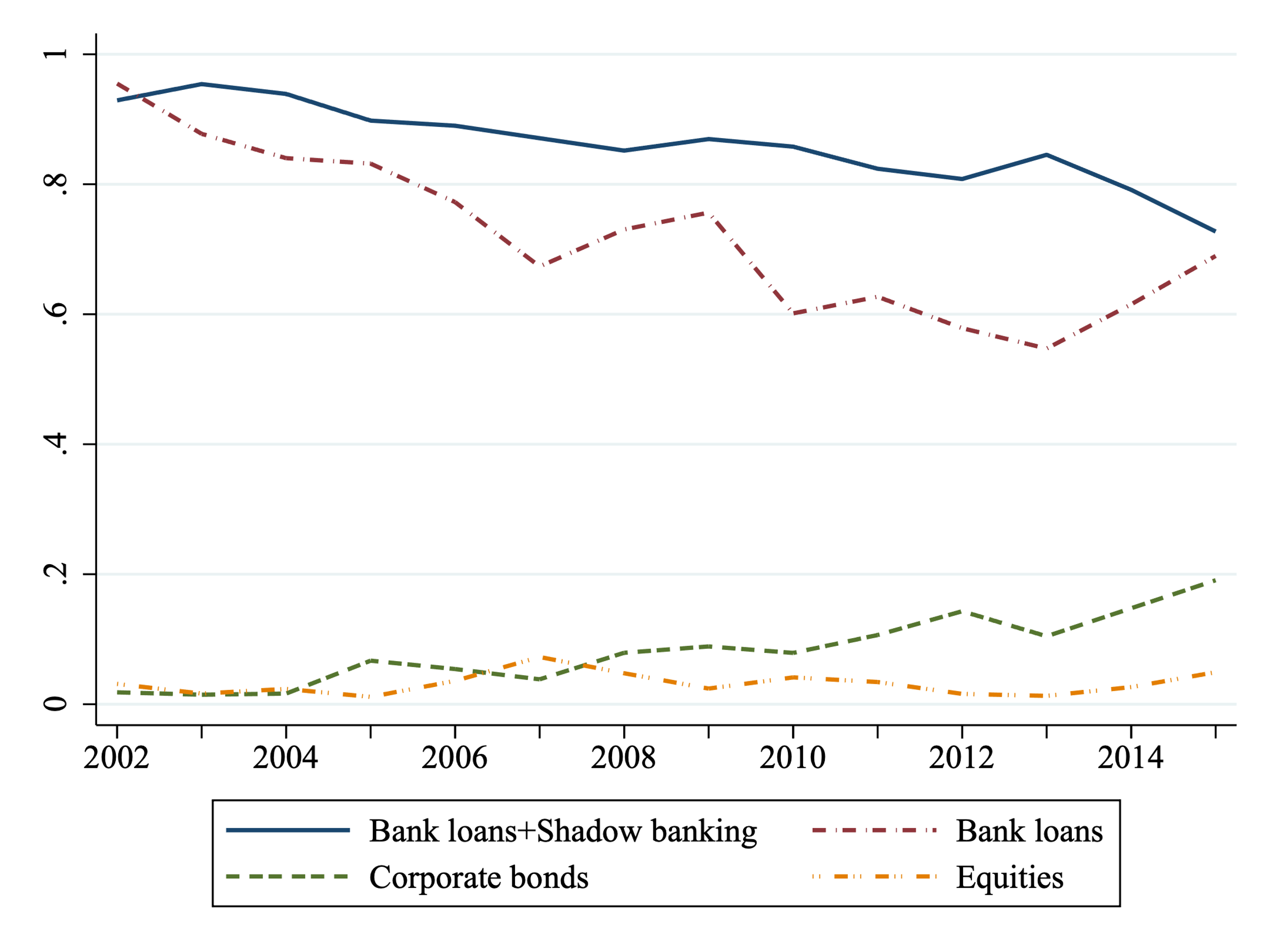

China’s financial system consists of a state-owned, regulated, and (arguably) monopolistic banking sector, a less formal and decentralized direct lending market, an equity market, and a growing bond market. While there is no official data on the scale of informal lending, Figure 1 shows in time series the size and importance of the other parts of China’s financial system, relative to total financing (i.e., excluding informal lending). Note the small equity market and, more importantly, the relative decline in banking and the rise of the bond market over the same period.

Figure 1: Composition of aggregate financing in China

Source: The aggregate social financing dataset in CEIC.

Notes: This figure shows bank loans, corporate bonds, and equities as fractions of aggregate financing (excluding informal lending) from 2002 to 2015. Bank loans refer to loans in local or foreign currencies; shadow banking refers to trust loans, entrusted loans, and banker’s acceptance bills; corporate bonds refer to corporate bond financing; and equities refer to nonfinancial enterprise equity financing.

The largest banks in China are state owned and dominate the economy’s banking sector. They are subject to state regulations, but the past twenty years have seen reforms that gave commercial banks greater flexibility in decision making, especially with respect to interest rates on loans and deposits. Before 2004, interest rates in the banking sector were tightly regulated by China’s central bank, by way of setting policy interest rates (on bank loans and deposits) and interest rate ceilings and floors around those policy rates. The lending rate ceilings were removed in October 2004, the floors were removed in July 2013, and by 2015 the central bank had also released control of the interest rates on deposits.

China’s bond market, where the majority of contracts traded are government and corporate bonds, has grown substantially over the past two decades, from virtual nonexistence to the third largest in the world.

Private lending is institutionally part of the economy’s total lending, which is carried out independent of bank loans and the market for corporate bonds. In practice it involves a range of informal sources used by Chinese enterprises and firms, including interpersonal lending, trade credit, money lenders, loan sharks, and other less delegated monitors such as peer-to-peer platforms. How important is private lending in China’s financial system? Little systematic information exists about the scale of private lending in China, but some studies suggest it is quite large (e.g., Li 2006; Lu et al. 2015), relative to the economy’s total external finance.

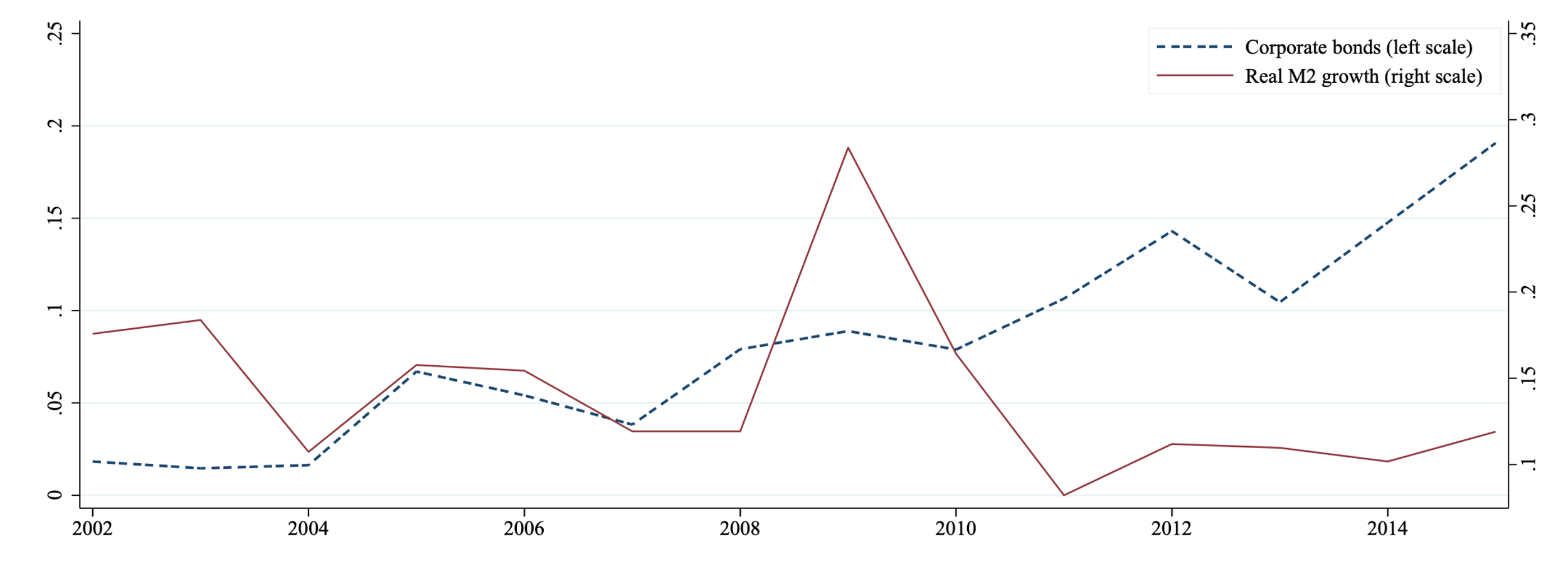

What determines the size and composition of China’s credit markets? Based on a dataset from 1998–2017, Chen, Ren, and Zha (2018) show that the growth of bank loans is in line with the growth of M2. Does M2 growth also play a role in determining the composition of China’s financial system? Panels (a) and (b) in Figure 2 seem to suggest that a decrease in the supply of credit shifts the composition of aggregate finance toward bond finance and away from bank loans.

Panel (a)

Panel (b)

Figure 2: Shares of banking and corporate bonds vs. real M2 growth

Source: CEIC.

Notes: Banking denotes the fraction of bank loans (including shadow banking) in aggregate financing (excluding informal lending) based on CEIC’s aggregate social financing data. Corporate bonds denote the fraction of corporate bonds in aggregate financing (excluding informal lending), again based on CEIC’s aggregate social financing data. Real M2 growth is calculated by subtracting the aggregate CPI inflation rate from the nominal M2 growth rate.

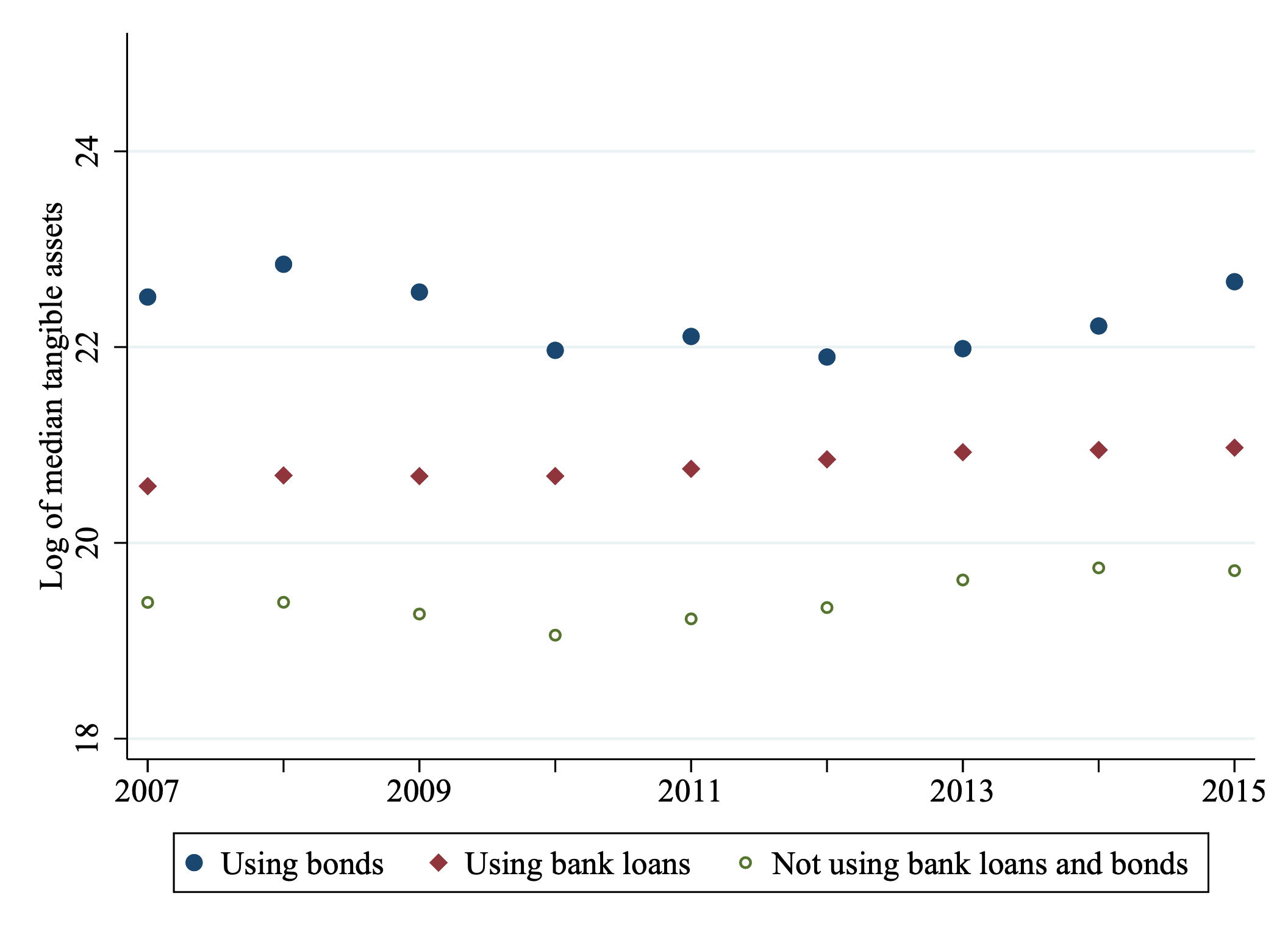

A hallmark of China’s banking sector is the uneven distribution of bank loans between smaller and larger firms. There is wide documentation and public discussion of the difficulties small firms face in obtaining bank loans. The World Bank Enterprise Survey for China (2012) shows that the fraction of firms using bank loans for investment financing is, on average, much lower in China than in other countries. For the small firms in their survey, it is 3.8% in China, 17.7% in East Asia and Pacific, and 22.2% across all countries. In addition, as shown in Figure 3, firms that use bonds as a means of finance are much larger than those using bank loans who, in turn, are larger than those who use neither bonds nor bank loans. Didier et al. (2014) observe a similar pattern with a larger set of countries.

Figure 3: Firm size and financing instruments

Source: CSMAR, publicly listed nonfinancial firms.

Notes: Solid dots represent the median of tangible assets in firms that use bonds (and possibly other instruments) for finance. Solid squares represent the median of tangible assets in firms that use bank loans (and possibly other instruments) for finance. Hollow dots represent the median measure of tangible assets of all other firms in the dataset.

To develop a theory for China’s financial system, in our recent paper, we take a classical approach in modeling lending and financial intermediation where, following Diamond (1984) and Williamson (1986), lending is subject to costly state verification (CSV) and the bank is a delegated monitor. Firms (borrowers) differ in net worth, which is used as equity, as well as collateral for mitigating the effects of CSV and limited liability (Bernanke and Gertler 1989). Being a delegated monitor, the bank is more efficient in lending than individual investors. Private lending coexists with bank lending because the low (regulated) deposit interest rate induces investors to participate in private lending for higher returns, or because a tight supply of credit dictates a sufficiently high interest rate on private lending to compete credit away from banking. On the other hand, that in equilibrium the bank lends to firms with larger net worth is because, relative to the bank, individual lenders have a comparative advantage in financing smaller rather than larger projects. Larger firms, with greater net worth to support more investment, make the bank a more efficient monitor. Meanwhile, financing smaller projects in nondelegated lending requires less repetition in monitoring the firm’s financial report. Larger firms also find bond finance favorable, as their large net worth allows them to raise sufficient financing without resorting to costly monitoring.

With a fixed deposit interest rate, the model predicts that an expansion in the supply of external finance (M) would increase bank loans (which equals bank deposits D) but reduce direct lending, in both absolute and relative terms, increasing the size of banking relative to direct finance. Why is this? Imagine the economy starts from an initial equilibrium where direct lending (i.e., M-D) and bank loans coexist. Imagine M is increased by a small positive amount Δ. Any fraction of this Δ could not have flowed into the market for direct lending, as the interest rate on direct lending would fall and investors would flow into bank deposits. In other words, the newly available Δ must become an addition to bank deposits, which now total D' ≡ D+Δ, D denoting the initial deposits. Given D', however, the bank would re-optimize to expand its loan portfolio (firms to which a loan is offered). This, in turn, would take firms away from direct lending, reducing the demand for direct lending, lowering the interest rate, and driving investors away from direct lending and into bank deposits, until the interest rate on direct lending is restored at RD. This process would again increase bank deposits, say from D' to D'' (> D'). But then the bank must again reoptimize, with the new D''. And this continues until bank deposits settle at a new equilibrium, which is strictly greater than the equilibrium prior to the increase in M. To summarize, the exogenous increase in M results in, through a multiplier effect, a greater increase in deposits and bank loans.

We then use the model for policy analysis, studying as an example the effects of a major 2004 banking reform in China that removed the interest rate ceiling on commercial bank loans. We find that such a reform should alter commercial banks optimal lending strategy. Specifically, prior to the reform, banks kept loans to a minimum size—by keeping loans small, they could lend to more firms, maximizing the utilization of firm net worth as collateral for enforcing loan repayments. After the reform and with a flexible lending rate, banks optimized instead by making larger loans while charging higher interest rates, as larger loans lower the cost per unit of lending. Once the ceiling was lifted, banks removed larger firms from their portfolios and replaced them with smaller firms. Larger firms, given their greater net worth for supporting internal finance, have less need for external financing. This expanded the market for bonds—the larger firms, upon leaving the bank, raised financing by issuing bonds—and at the same time reduced private lending. And the story continues. As the adjustment in bank portfolios increases demand for direct financing, the interest rate on direct lending rises. This, in turn, induces individual investors to substitute bank deposits for direct lending, cutting D and lowering the interest rate on direct lending. With a smaller D, banks must again adjust their loan portfolios to make them even smaller, moving more (larger) firms into the market for direct lending, again raising the interest rate there, inducing more investors to leave banking. And this goes on until the market settles at a new equilibrium with a smaller amount of bank deposits, a larger bond market, and less private lending. In summary, the model suggests that the 2004 reform should have resulted in a decline in banking, an increase in bond finance, and a decrease in private lending.

Does the model make sense empirically? Following the theoretical analysis, we move on to seek empirical support for the model’s predictions. We discuss two types of empirical evidence in the paper, based on our own findings and what was already developed in the literature, respectively. We target two of our model’s major predictions, regarding, respectively, the effects of a credit supply expansion and the impact of the 2004 banking reform. We use two datasets in our own empirical work. The first is from CEIC at the macro level and second is from CSMAR at firm level. Our empirical results based on both datasets are consistent with the model’s prediction that increasing the supply of external finance shifts the composition of the financial system toward bank loans, and away from bonds and private lending. In addition to our own work, an existing empirical literature on corporate finance demonstrates that the 2004 reform tends to increase both the sizes and the lending rates of bank loans, consistent with the model’s prediction on the effects of the reform (e.g., Chen and Ma 2018, Wang et al. 2022, Xuan et al. 2022).

To summarize, we model China’s financial system where private information and banking regulations give rise to the coexistence of bank loans, corporate debt, and private lending. The equilibrium distribution of credit is such that smaller net worth firms obtain financing from private lenders, larger firms do so through bank loans, and the largest do so by way of corporate debt. Our model implies that a contraction in the supply of credit should cut bank loans but increase corporate bonds. It also suggests that the 2004 banking reform, which removed the lending rate ceiling, should have reduced bank loans but increased bond finance, by way of altering banks’ optimal lending portfolio. Our work thus implies that the 2004 reform and the contractionary monetary policy during 2009–15 may offer an explanation for the observed decline of China’s banking sector.

References

Bernanke, Ben, and Mark Gertler. 1989. “Agency Costs, Net Worth, and Business Fluctuations.” American Economic Review 79 (1): 14–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1804770.

Chen, Shenglan, and Hui Ma. 2018. “Loan Accessibility and Firm Business Credit: Quasi-Natural Experimental Evidence from China’s Interest Rate Marketization Reform.” Management World 34 (11): 108–20, 149. https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2018.0009.

Chen, Kaiji, Jue Ren, and Tao Zha. 2018. “The Nexus of Monetary Policy and Shadow Banking in China.” American Economic Review 108 (12): 3891–3936. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20170133.

Diamond, Douglas W. 1984. “Financial Intermediation and Delegated Monitoring.” Review of Economic Studies 51 (3): 393–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297430.

Didier, Tatiana, Ross Levine, and Sergio. L. Schmukler. 2014. “Capital Market Financing, Firm Growth, Firm Size Distribution,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20336. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20336.

Jianjun, Li. 2006. “The Survey on Underground Financing in China.” Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Press.

Lu, Yunlin, Haifeng Guo, Erin H. Kao, and Hung-Gay Fung. 2015. “Shadow Banking and Firm Financing in China.” International Review of Economics and Finance 36: 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2014.11.006.

Luo, Jie, and Cheng Wang. 2024. “Banking and Banking Reforms in China in a Model of Costly State Verification.” International Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/iere.12744.

Wang, Jingru, Hongjian Wang, Xinghe Liu, and Qingyuan Li. 2022. “Credit Availability and Classification Shifting: Based on the Quasi-Natural Experiment of the Bank Lending Interest Rate Ceiling Deregulation.” China Journal of Accounting Studies 10 (1): 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/21697213.2022.2082722.

Williamson, Stephen D. 1986. “Costly Monitoring, Financial Intermediation, and Equilibrium Credit Rationing.” Journal of Monetary Economics 18 (2): 159–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(86)90074-7.

Xuan, Yang, Qinglu Jin, and Xiaoxue Li. 2022. “Interest Rate Marketization, Credit Allocation, and the Value of Growth Options in Non-SOEs: Evidence from the Removal of Upper and Lower Limits of the Loan Interest Rate.” Journal of Financial Research 5: 76–94. http://www.jryj.org.cn/CN/Y2022/V503/I5/76.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email