Pricing the Priceless: The Financing Cost of Biodiversity Conservation

The accelerating loss of biodiversity has become a global concern (Johnson et al. 2021). Addressing this issue involves handling a tension between improving efforts to protect and restore biodiversity for long-term sustainable development and managing the significant short-term costs associated with the conservation activities. Prior studies have evaluated the direct economic costs of this transition (IPBES 2019, Deutz et al. 2020) and the asset pricing implications of biodiversity risk (Coqueret, Giroux, and Zerbib 2025; Garel et al. 2024; Giglio et al. 2023, 2024). However, the financing cost of biodiversity conservation and its implications for financial markets remain largely unexplored (Karolyi and Tobin-de la Puente 2023, Starks 2023).

Our research investigates the Green Shield Action (GSA) in China, one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, with over 140,000 recorded species, as documented in the Catalogue of Life China. This landmark regulatory initiative, launched in 2017 by the central government, targets rampant illegal activities in national nature reserves (NNRs), including mining, tourism, and hydropower energy generation. GSA leaves little discretion to local governments in terms of implementation (Wang, He, and Liu 2023), effectively requiring municipal authorities to shut down economic activities within NNRs and to invest in conservation efforts.

To analyze the financial impact of GSA, we focus on municipal corporate bonds (MCBs)—a key source of funding for city governments in China. Unlike corporations, municipalities cannot relocate to avoid their responsibilities of protecting and restoring NNRs within their jurisdiction. Thus, MCB investors must account for such local risks. Our analysis relies on several datasets, including geographic information on the boundaries of NNRs, issuance and trading data of MCBs, regional development characteristics, and other alternative datasets such as remote-sensing land cover, government procurement, newspaper coverage, and birdwatching reports. Our baseline empirical strategy relies on a difference-in-differences (DiD) methodology, which compares municipalities with NNRs (i.e., NNR municipalities) to those without (i.e., non-NNR municipalities) around the implementation of GSA.

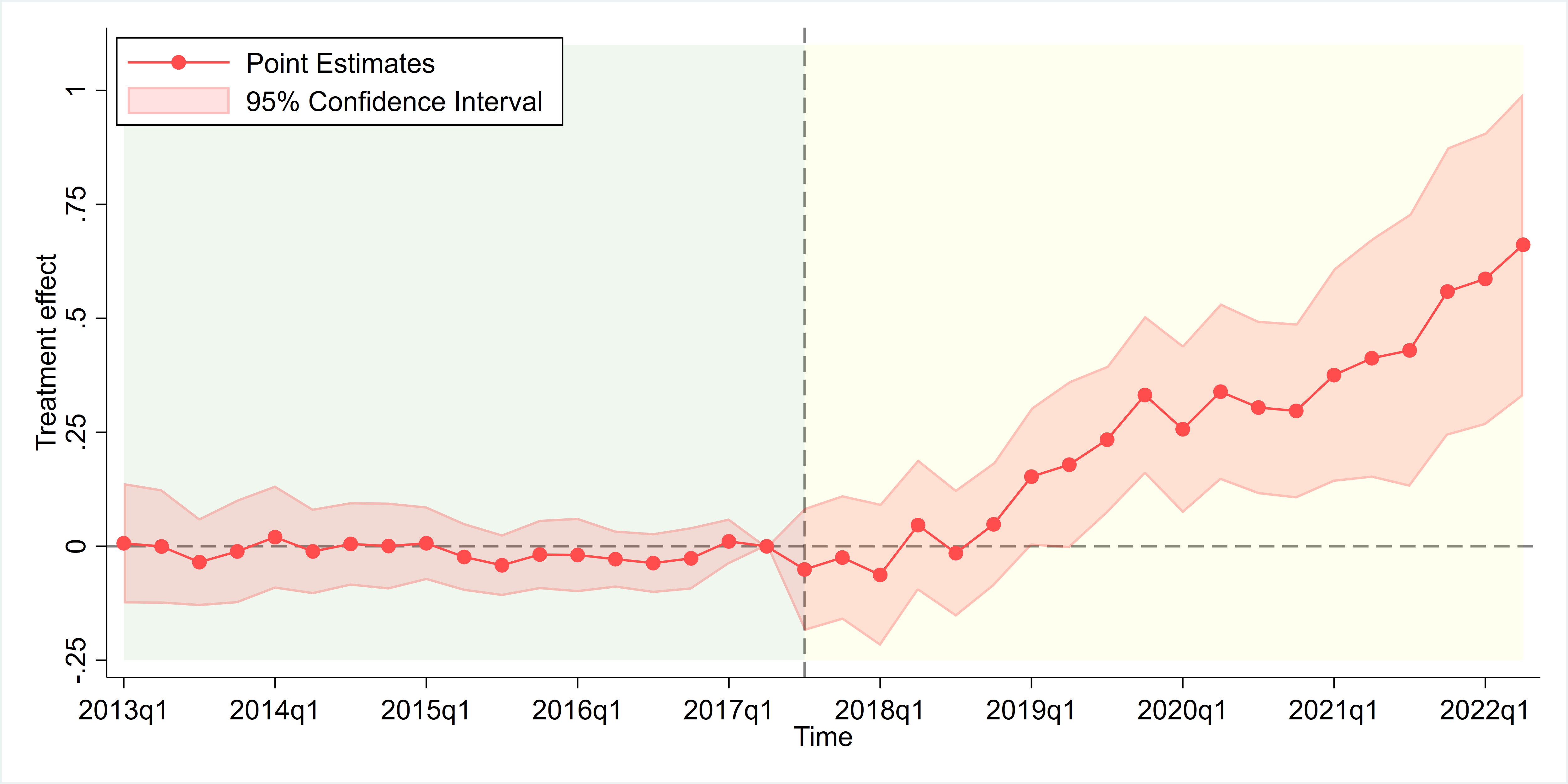

We find that NNR and non-NNR municipalities exhibited similar trends in their bond spread in the period before the announcement of the GSA. Following the launch of the GSA and as investors learned how the central government was indeed committed to enact this enforcement action, NNR municipalities experienced a significant increase in MCB yield spreads relative to non-NNR municipalities (Figure 1). This effect was robust to using alternative measures of MCB yields, to several sample restrictions, and to accounting for the potential confounding effects of other policies.

Figure 1: Changes in MCB Spreads Before and After GSA

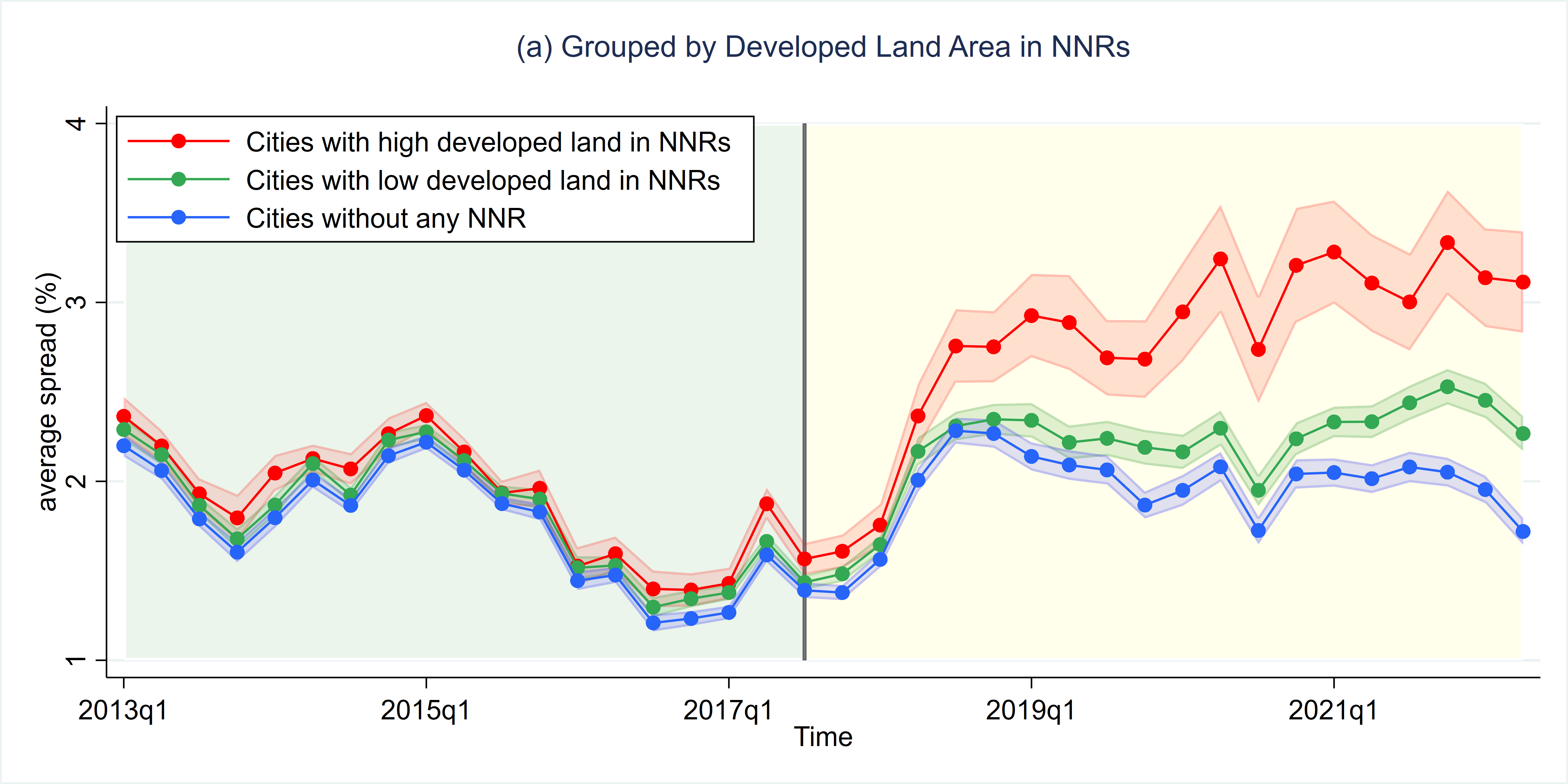

We also examine the mechanisms through which GSA influenced the required risk premium from MCB investors. As shown in Figure 2, the level of preexisting economic activity played a critical role: municipalities with higher developed land within reserves before the GSA were likely to face greater restoration costs due to the reform, plausibly leading to larger increases in MCB yield spreads. In addition, we observe a notable rise in the proportion of NNR-related projects in local government procurement as GSA progressed, indicating that local governments indeed added substantial investments in biodiversity conservation following GSA. As for the overall local fiscal conditions, we find that transition costs imposed by GSA worsened fiscal pressures of NNR municipalities, heightening investor concerns about public creditworthiness. This effect was particularly pronounced in regions with heavier debt burdens and for shorter-maturity bonds.

Figure 2: The Dynamics of MCB Spreads over Time across Groups with Different Levels of Preexisting Economic Activities within NNRs

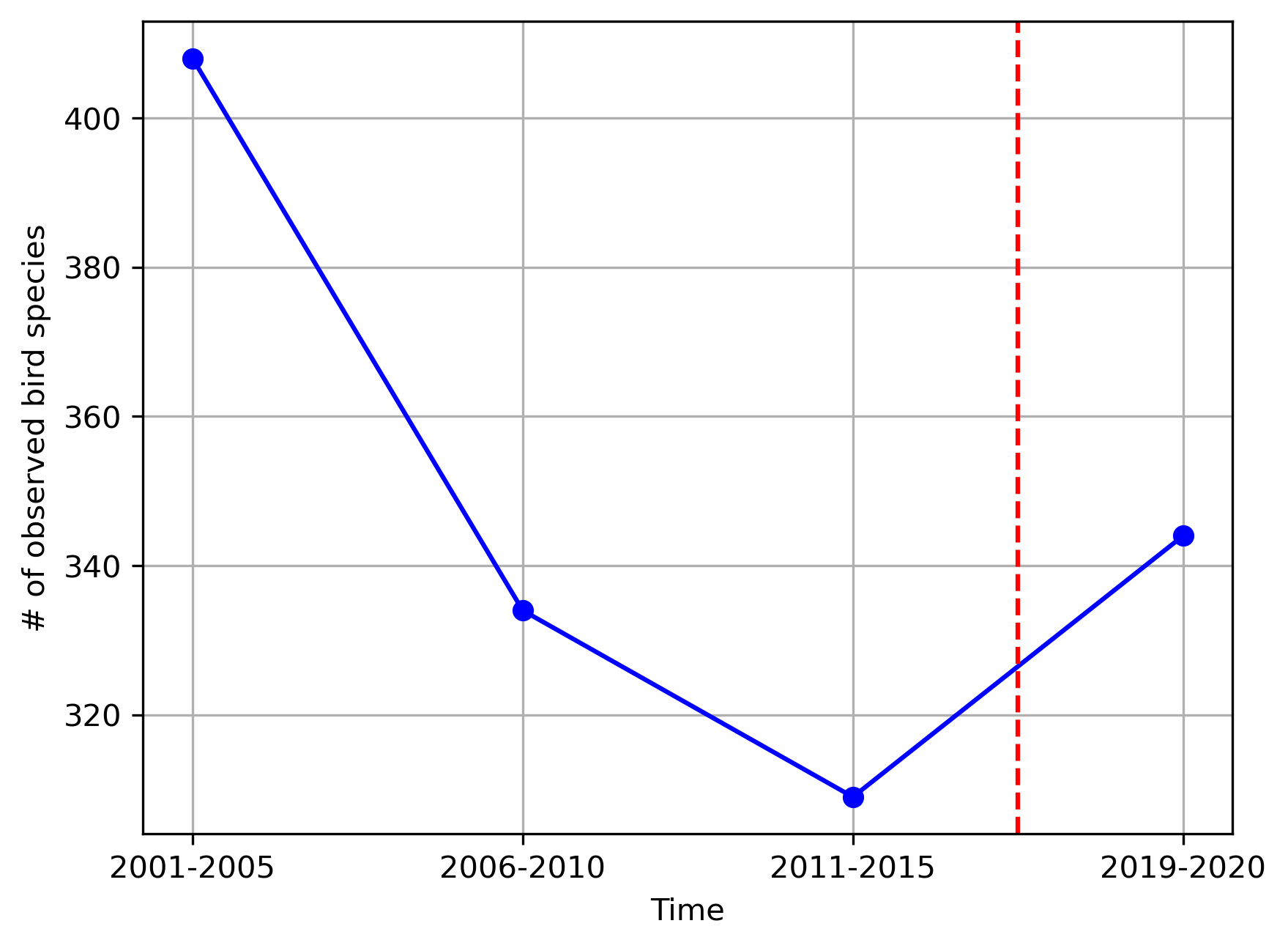

We find that GSA successfully curbed species loss and improved local biodiversity (Figure 3). However, there is no evidence that investors significantly rewarded NNR municipalities that showed effective ecological performance—regions with greater biodiversity improvements did not enjoy more favorable financing conditions. We also assess the level of media coverage for each NNR and find that cities with better-known NNRs did not respond differently to GSA. This largely rules out that punitive pricing by investors in response to the poor NNR management revealed by GSA drive the findings.

Figure 3: The Dynamics of Bird Species Observed by Forest Investigation Stations over Time

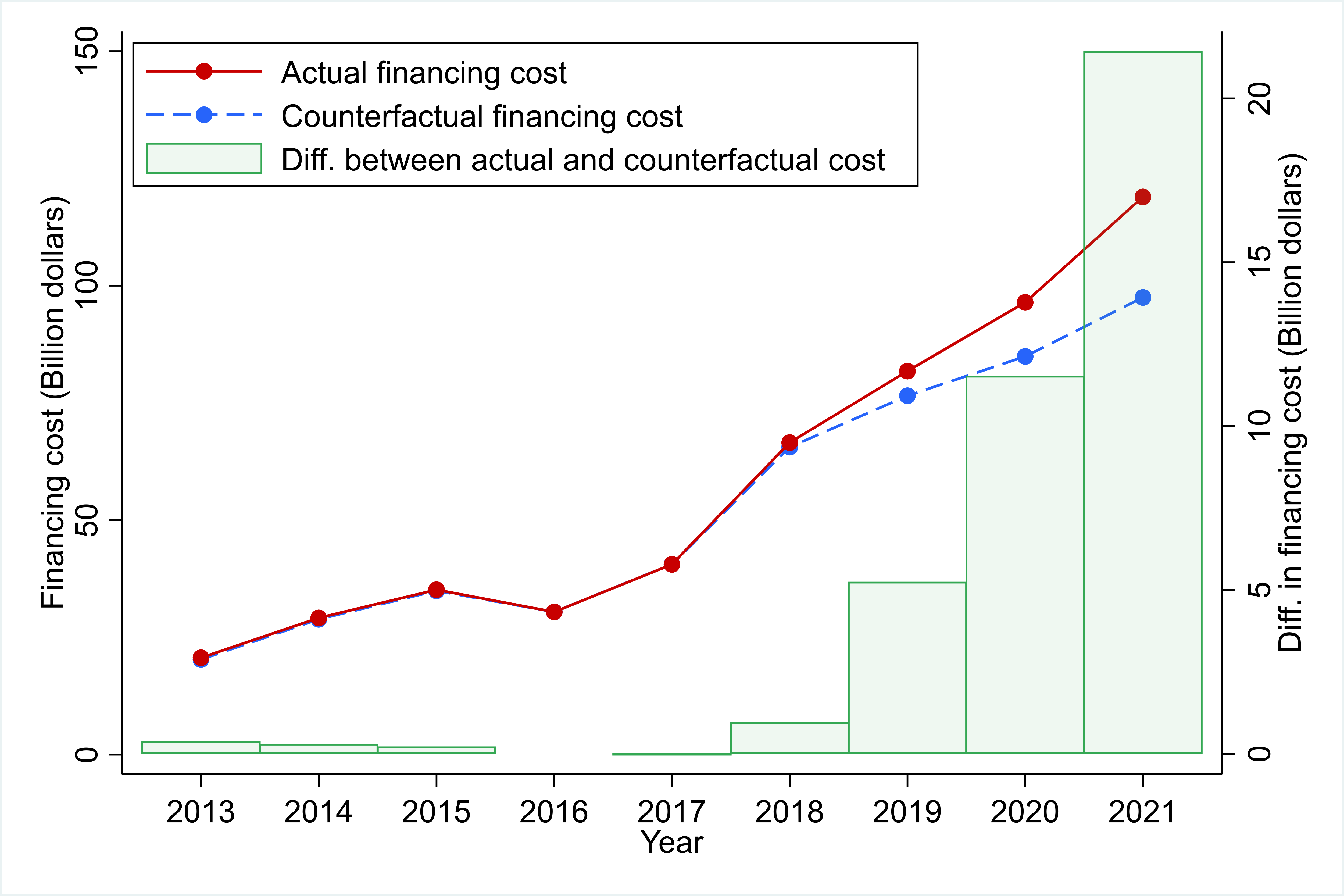

Lastly, we provide a back-of-the-envelope estimate of the aggregate additional financing costs incurred. The analysis reveals that the efficiency losses due to these financial frictions are economically significant (Figure 4), emphasizing the need for more efficient mechanisms to align ecological objectives with financial market frictions.

Figure 4: Local Public Debt Cost Comparison of True Value and Counterfactual Estimates

Our research reveals that while top-down conservation efforts by central governments yield significant ecological benefits, they also impose financial burdens on local governments. Our evidence on the costs and benefits of biodiversity conservation offers important policy implications. Specifically, governments must carefully account for financing costs incurred when implementing conservation policies. We advocate developing dedicated financial vehicles, rather than relying on general budgets, to address the biodiversity financing gap, manage risk spillovers, and attract impact investors. Following COP15, a dedicated fund was established under the Global Environment Facility (GEF) to finance the objectives of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). However, as of October 2024, only twelve countries have collectively pledged a total of $396 million. Our study resonates with the shared challenges highlighted during COP16, particularly “the lack of a definition for a financing model to bring the biodiversity protection plan to reality.” Moreover, our study suggests that the allocation by the central government should strategically consider the expected regional environmental benefits, local governments’ fiscal conditions, and the composition and education of investors. This would enable more efficient achievement of policy targets, as well as more effective interaction with market forces (Flammer et al. 2025).

(Fukang Chen and Minhao Chen are PhD candidates at the School of Finance, Renmin University of China; Haoyu Gao is a professor of finance at the School of Finance, Renmin University of China; Lin William Cong is the Rudd Family Professor of Management and Professor of Finance at the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business and the National Bureau of Economic Research; and Jacopo Ponticelli is an associate professor of finance at the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, and a research associate at Centre for Economic Policy Research and the National Bureau of Economic Research.)

References

Chen, Fukang, Minhao Chen, Lin William Cong, Haoyu Gao, and. Jacopo Ponticelli. 2024. “Pricing the Priceless: The Financing Cost of Biodiversity Conservation.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 32743. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4908556.

Coqueret, Guillaume, Thomas Giroux, and Olivier David Zerbib. 2025. “The Biodiversity Premium.” Ecological Economics 228: 108435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108435.

Deutz, Andrew, Geoffrey M. Heal, Rose Niu, Eric Swanson, Terry Townshend, Zhu Li, Alejandro Delmar, Alqayam Meghji, Suresh A. Sethi, and John Tobin-de la Puente. 2020. “Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap.” Paulson Institute, Nature Conservancy, and Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26226.32968.

Flammer, Caroline, Thomas Giroux, and Geoffrey M. Heal. 2025. “Biodiversity Finance.” Journal of Financial Economics 164: 103987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2024.103987.

Garel, Alexandre, Arthur Romec, Zacharias Sautner, and Alexander F. Wagner. 2024. “Do Investors Care About Biodiversity?” Review of Finance 28 (4): 1151–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfae010.

Giglio, Stefano, Theresa Kuchler, Johannes Stroebel, and Xuran Zeng. 2023. “Biodiversity Risk.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 31137. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31137.

Giglio, Stefano, Theresa Kuchler, Johannes Stroebel, and Olivier Wang. 2024. “The Economics of Biodiversity Loss.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 32678. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32678.

IPBES. 2019. “Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” Edited by Eduardo Brondizio, Sandra Díaz, Josef Settele, and Hien T. Ngo. IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673.

Johnson, Justin Andrew, Giovanni Ruta, Uris Baldos, Raffaello Cervigni, Shun Chonabayashi, Erwin Corong, Olga Gavryliuk, James Gerber, Thomas Hertel, Christopher Nootenboom, Stephen Polasky, James Gerber, Giovanni Ruta, and Stephen Polasky. 2021. “The Economic Case for Nature: A Global Earth-Economy Model to Assess Development Policy Pathways.” https://hdl.handle.net/10986/35882.

Karolyi, G. Andrew, and John Tobin-de la Puente. 2023. “Biodiversity Finance: A Call for Research into Financing Nature.” Financial Management 52 (2): 231–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12417.

Starks, Laura T. 2023. “Presidential Address: Sustainable Finance and ESG Issues—Value versus Values.” Journal of Finance 78 (4): 1837–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13255.

Wang, Weiye, Suyuan He, and Jinlong Liu. 2023. “Understanding Environmental Governance in China Through the Green Shield Action Campaign.” Journal of Contemporary China 33 (149): 739–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2023.2244893.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email