Free Education's Impact on Schooling Outcomes: Direct Effects and Intra-household Spillovers

As one of the UN Millennium Development Goals, improving human capital accumulation in developing countries has been a key focus. Many countries have implemented programs to reduce education costs, including eliminating school fees, providing vouchers, scholarships, and various conditional transfer programs. Recent studies show that community interactions create spillover effects on schooling decisions. While research has demonstrated the importance of inter-household spillover effects on individual schooling decisions, few studies have examined the intra-household spillover effects on children's short and long-term human capital accumulation.

Studying intra-household spillover effects is crucial for understanding policy impacts. When some children receive educational benefits, parents may redistribute family resources, affecting siblings who are not eligible for the program. However, researching these effects faces two main challenges: finding programs that target specific children within families, and obtaining data on both eligible and ineligible children, as most programs only track enrolled participants.

We study intra-household resource allocation in education using China's "Two Exemption One Subsidy" program, which provides free compulsory education in rural areas. Implemented in western counties in 2006 and nationwide in 2007, this program eliminates school fees for primary and middle school students. We analyze its effects using a difference-in-differences approach based on varying pre-policy school fees across counties. The program uniquely targets children still in compulsory education, allowing us to examine spillover effects on their siblings who have completed middle school.

Based on the National Fixed Point Survey data, our analysis reveals substantial positive direct effects of the free education policy. Specifically, the school enrollment rate increases by 10.23% and 10.47% for eligible boys and girls aged 12 to 15 and by 44.26% and 62.33% for those aged 16 to 20, respectively. Moreover, for the older age group, we find a transition from work to school, that is, the employment of eligible boys and girls aged 16 to 20 decreases by 18.83% and 22.03%, respectively.

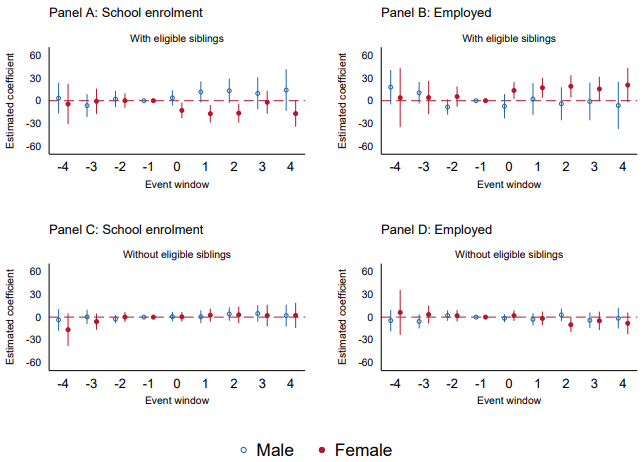

Perhaps the most striking findings emerge in the analysis of intra-household spillover effects. Fewer ineligible sisters with eligible siblings enroll in high school and they start to work after the program. That is, their high school enrollment rate decreases by 35.4% and their employment increases by 83.5%. Panels A and B of Figure 1 graphically show these negative effects on ineligible sisters but not on ineligible brothers. Further analysis shows that these negative spillover effects are particularly pronounced for girls with eligible brothers, suggesting that households redirect resources toward sons' education when given the opportunity. We also find no effects on ineligible children without eligible siblings, as shown in Panels C and D of Figure 1.

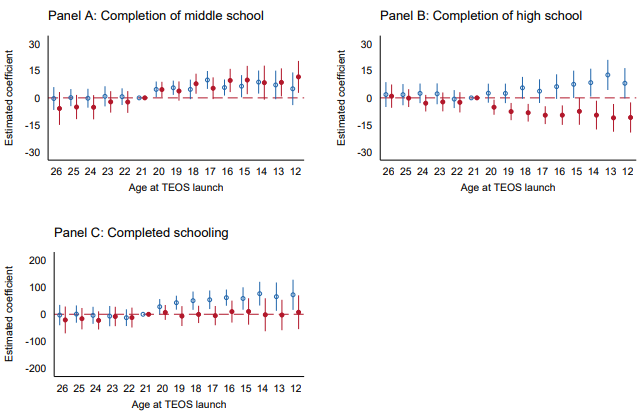

Figure 2 demonstrates the policy's long-term impacts, highlighting persistent gender inequalities. Males who benefited from the program show improved educational outcomes, with 13.83% higher middle school completion rate and 0.7 more total years of education. However, while females show improved middle school completion rate by 16.63%, they experience 45.19% lower high school completion rate, resulting in no net gain in their overall years of education.

In sum, our results underscore the importance of considering the intra-household spillover effects to obtain a full picture of the policy impact. In particular, a gender-neutral policy can have an asymmetric effect on males and females because of household budget constraints and son preference. This unexpected negative spillover effect increases the gender inequality in education.

Our research adds to existing studies on how reducing education costs affects school attendance. Prior research has examined various cost-reduction approaches, including eliminating school fees (Shi, 2016; Xiao et al., 2017), providing vouchers, stipends, and scholarships (Duflo et al., 2021), and implementing conditional transfer programs (Duflo et al., 2015; Muralidharan and Prakash, 2017; Parker and Todd, 2017). While previous studies on fee waiver programs have shown positive effects on attendance, particularly for disadvantaged students and girls, our research uniquely separates direct and spillover effects, specifically highlighting how intra-household resource allocation influences educational outcomes for ineligible siblings.

Recent research has focused on inter-household educational spillovers through neighborhood and community interactions. However, studies on intra-household spillovers are limited and focus on randomized controlled trials. While Barrera-Osorio et al. (2011) find negative spillover effects on ineligible sisters in Colombian conditional cash transfer programs, studies by Ferreira et al. (2017) and Galiani and McEwan (2013) find no spillover effects in Cambodia and Honduras. Our study differs by examining a nationwide quasi-natural experiment and analyzing both short-term and long-term educational outcomes.

In addition to China, school fees at the primary and middle school levels are prevalent in developing countries around the world, and many countries have also removed their fees for compulsory education in recent decades. For instance, primary schools became free in Nigeria in 1976, Indonesia in 1978, Malawi in 1991, Ethiopia in 1994, Uganda in 1996, Tanzania in 2002, and Ghana and Kenya in 2003. Moreover, middle school fees have been gradually eliminated across countries, such as Gambia in 2001 and Ghana in 2003. The findings in rural China, especially the negative spillover effects on girls, can provide useful lessons for other developing countries.

Figure 1: Short-Run Effects on Ineligible Children

Figure 2: Long-Run Effects on Educational Outcomes

References

Barrera-Osorio, F., Bertrand, M., Linden, L.L. and Perez-Calle, F. (2011). ‘Improving the design of conditional transfer programs: Evidence from a randomized education experiment in Colombia’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 3(2), pp. 167–195.

Duflo, E., Dupas, P. and Kremer, M. (2015). ‘Education, HIV, and early fertility: Experimental evidence from Kenya’, American Economic Review, vol. 105(9), pp. 2757–97.

Duflo, E., Dupas, P. and Kremer, M. (2021). ‘The impact of free secondary education: Experimental evidence from Ghana’, NBER Working Paper.

Ferreira, F.H., Filmer, D. and Schady, N. (2017). ‘Own and sibling effects of conditional cash transfer programs: Theory and evidence from Cambodia’, Research on Economic Inequality, vol. 25, pp. 259–298.

Galiani, S. and McEwan, P.J. (2013). ‘The heterogeneous impact of conditional cash transfers’, Journal of Public Economics, vol. 103, pp. 85–96

Guo, Naijia, Shuangxin Wang, and Junsen Zhang. 2024. “The Short- and Long-Run Impacts of Free Education on Schooling: Direct Effects and Intra-Household Spillovers.” The Economic Journal, 134(663): 2876–2911.

Muralidharan, K. and Prakash, N. (2017). ‘Cycling to school: Increasing secondary school enrollment for girls in India’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 9(3), pp. 321–50.

Parker, S.W. and Todd, P.E. (2017). ‘Conditional cash transfers: The case of Progresa/Oportunidades’, Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 55(3), pp. 866–915.

Shi, X. (2016). ‘The impact of educational fee reduction reform on school enrolment in rural China’, The Journal of Development Studies, vol. 52(12), pp. 1791–1809.

Xiao, Y., Li, L. and Zhao, L. (2017). ‘Education on the cheap: The long-run effects of a free compulsory education reform in rural China’, Journal of Comparative Economics, vol. 45(3), pp. 544–562.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email