Consumer-Financed Fiscal Stimulus Evidence from Digital Coupons in China

In 2020, local governments in China began issuing digital coupons to stimulate spending in targeted categories such as restaurants and supermarkets. We find that the coupons caused large increases in spending of 3.1–3.3 yuan per yuan spent by the government. The large spending responses do not come from substitution away from non-targeted spending categories or from short-run intertemporal substitution. We conclude that digital coupons are a cost-effective way to provide targeted fiscal stimulus to specific sectors of the economy.

Many governments distribute stimulus payments during economic downturns to increase consumption (Johnson, Parker, and Souleles 2006; Shapiro and Slemrod 2009; Parker et al. 2022 ). Many governments also design stimulus policies to target particular sectors of the economy. For example, during the Great Recession, the US government provided targeted financial support for the automobile industry through the “cash for clunkers” program and supported the housing market through a new first-time homebuyer tax credit (Mian and Sufi 2012 ; Berger, Turner, and Zwick 2020).

More recently, during the COVID-19 recession, the Chinese government carried out a novel form of fiscal stimulus using publicly financed digital coupons. The coupons were delivered through smartphone apps and were designed to stimulate spending in the sectors that were hit particularly hard during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., restaurants, grocery stores, and shopping malls). The coupons had fixed spending thresholds that had to be reached before consumers would receive money from the government (e.g., a coupon would give ¥18 off a food delivery order if the consumer spent at least ¥54).

In our paper (Ding et al. 2024), we estimate the effects of the coupons on consumer spending and evaluate the coupons’ effectiveness as a fiscal stimulus. To do this, we assemble data from a large online platform covering several types of coupons distributed across three Chinese cities. As a measure of cost-effectiveness, we define MPCcoupon as the increase in spending caused by a coupon relative to the coupon’s fiscal cost. For example, if 50,000 “Spend at least ¥54, get ¥18 off” food delivery coupons are used in a city, then the fiscal cost is ¥18 × 50,000 = ¥900,000. If the total increase in spending caused by the coupons is ¥1,800,000, then MPCcoupon = 2.0.

The reason that MPCcoupon can be larger than one is that many consumers may need to increase their spending substantially in the targeted spending categories to reach the spending threshold and take advantage of the coupon. If consumers do not decrease their spending in other categories, then their total spending would increase by more than the discount associated with the coupon. As a result, we call this new form of fiscal stimulus consumer-financed fiscal stimulus, since whenever MPCcoupon >1, the increased spending caused by the coupons is partly paid for by consumers.

Background and data. China’s stated aim of the coupon program was to stimulate consumption at a low fiscal cost. The coupons were distributed directly to consumers through preexisting technology platforms such as Alibaba, Jingdong, and Meituan. Once a coupon was acquired, it had to be redeemed within a short window before it expired. Our data comes from one of the large online e-commerce platforms that distributed the coupons in 2021, and we observe detailed transaction data for all of the consumers who acquired the coupons.

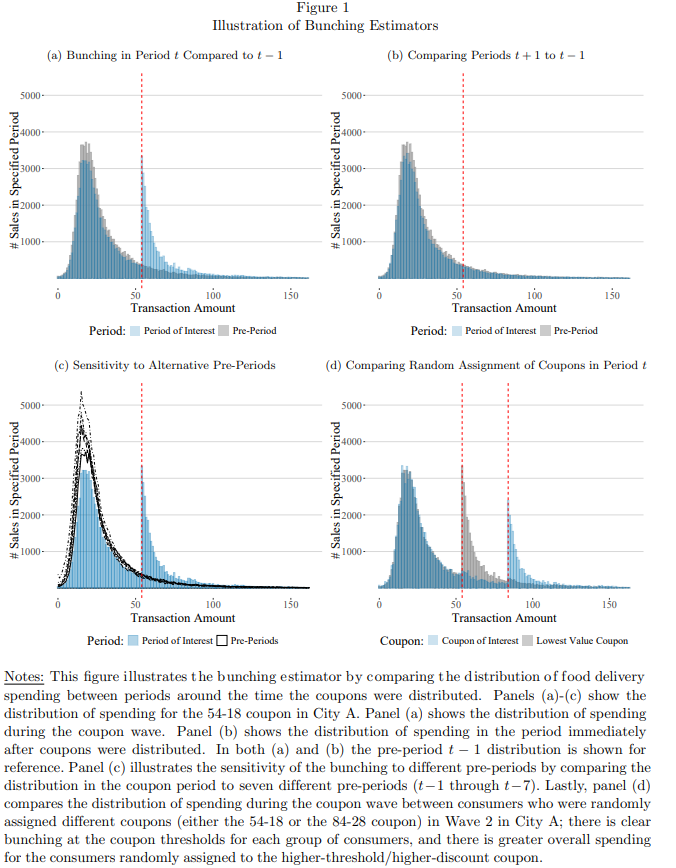

Empirical results. Figure 1 shows the transaction-level distribution of spending on food delivery in one specific city during the second wave of coupon distribution. Panels (a)-(c) show results for the “spend ¥54 get ¥18 off” (“54-18”) coupon. Panel (a) shows transaction amounts for both the period when the coupons were distributed and the prior period. Panel (b) shows transaction amounts in the periods before and after the coupons were available. Panel (c) shows transaction amounts for several additional pre-periods. Panel (d) compares the transaction amounts for consumers who were randomly assigned either the 54-18 or 84-28 coupons. Figure 1 shows clear evidence of bunching at the coupon thresholds in the period when the coupons were distributed, but not in any of the other pre-periods. We also see spending below the threshold decrease somewhat when the coupons were distributed, which suggests that the coupons caused some consumers to spend more than they otherwise would have in order to redeem the coupons.

We use these results to estimate MPCcoupon for each coupon in our data using a “bunching” estimation approach, following Best et al. (2020), Defusco, Johnson, and Mondragon (2020), and Cengiz et al. (2019). We find a range of MPCcoupon estimates from 1.9 to 4.6 depending on the coupon and city, with a weighted average of 3.1–3.3. Our MPCcoupon estimates are similar to the estimates reported in other recent studies of digital coupons in China using different data sets and research designs (Xing et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2021).

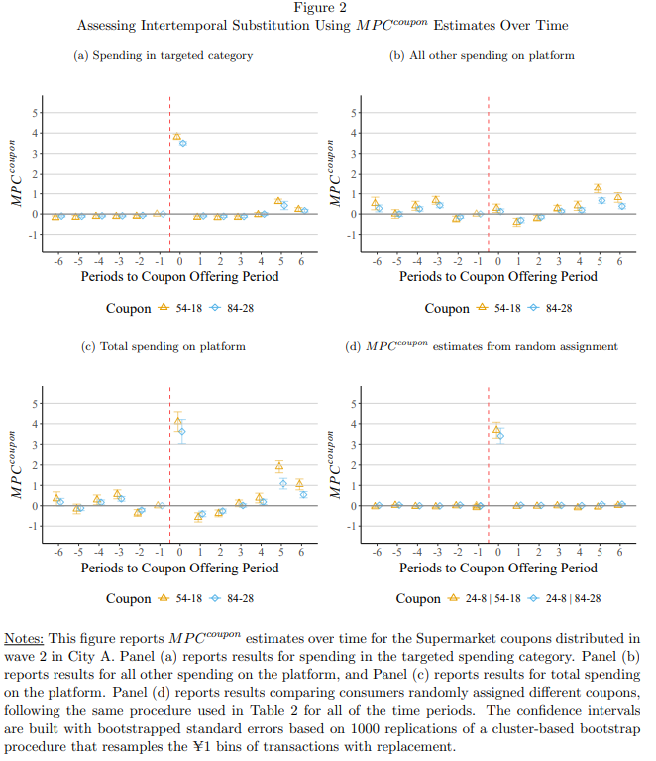

Interestingly, we find no evidence of substitution between “targeted” and “non-targeted” spending categories using data on all the consumers’ spending on the platform. We also find very little intertemporal substitution in the short run, with MPCcoupon estimates remaining fairly stable for several months after the coupons were distributed (see Figure 2 for more details). A likely explanation for the limited intertemporal substitution is that in our setting the coupons targeted non-durable goods (like food delivery and supermarkets).

An important limitation of the data is that we cannot observe “online-offline” substitution, although our heterogeneity analysis leads us to conclude that this potential bias is be limited. Additionally, we cannot match consumers who are in the same household, which is another potential margin of substitution. For example, a spouse who received a coupon might increase her spending at the expense of her spouse’s spending, which would reduce the aggregate effect of the coupons.

Conclusions. Our paper explains why China’s digital coupons are different than cash transfers and why our large MPCcoupon estimates are not surprising cash distributed by the government is likely to be primarily spent on non-targeted sectors and saved for the future, resulting in an MPC out of cash below one (see, e.g., Johnson, Parker, and Souleles 2006). The time-limited coupons, however, cause consumers to immediately increase spending in the targeted sectors, and the spending thresholds in the coupon designs lead to large behavioral responses that push MPCcoupon well above one. Overall, our results suggest that publicly financed digital coupons are a cost-effective way to provide targeted stimulus to specific sectors of the economy.

References

Berger, David, Nicholas Turner, and Eric Zwick. 2020. “Stimulating Housing Markets.” Journal of Finance 75 (1) 277–321. httpsdoi.org10.1111jofi.12847.

Best, Michael Carlos, James S. Cloyne, Ethan Ilzetzki, and Henrik J. Kleven. 2020. “Estimating the Elasticity of Intertemporal Substitution Using Mortgage Notches.” Review of Economic Studies 87 (2) 656–90. httpsdoi.org10.1093restudrdz025.

Cengiz, Doruk, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer. 2019. “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 134 (3) 1405–54. httpsdoi.org10.1093qjeqjz014.

Defusco, Anthony A., Stephanie Johnson, and John Mondragon. 2020. “Regulating Household Leverage.” Review of Economic Studies 87 (2) 914–58. httpsdoi.org10.1093restudrdz040.

Ding, Jing, Lei Jiang, Lucy Msall, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2024. “Consumer-Financed Fiscal Stimulus Evidence from Digital Coupons in China.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 32376. httpswww.nber.orgpapersw32376.

Johnson, David S., Jonathan A. Parker, and Nicholas S. Souleles. 2006. “Household Expenditure and the Income Tax Rebates of 2001.” American Economic Review 96 (5) 1589–1610. httpsdoi.org10.1257aer.96.5.1589.

Liu, Qiao, Qiaowei Shen, Zhenghua Li, and Shu Chen. 2021. “Stimulating Consumption at Low Budget Evidence from a Large-Scale Policy Experiment Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Management Science 67 (12) 7291–7307. httpsdoi.org10.1287mnsc.2021.4119.

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. 2012. “The Effects of Fiscal Stimulus Evidence from the 2009 Cash for Clunkers Program.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127 (3) 1107–42. httpsdoi.org10.1093qjeqjs024.

Parker, Jonathan A., Jake Schild, Laura Erhard, and David Johnson. 2022. “Economic Impact Payments and Household Spending during the Pandemic.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 30596. httpsdoi.org10.3386w30596.

Shapiro, Matthew D., and Joel Slemrod. 2009. “Did the 2008 Tax Rebates Stimulate Spending” American Economic Review 99 (2) 374–79. httpsdoi.org10.1257aer.99.2.374.

Xing, Jianwei, Eric Yongchen Zou, Zhentao Yin, Yong Wang, and Zhenhua Li. 2023 . “‘Quick Response’ Economic Stimulus The Effect of Small-Value Digital Coupons on Spending.” American Economic Journal Macroeconomics 15 (4) 249–304. httpsdoi.org10.1257mac.20210148.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email