Firm-to-Firm Referrals

Firm-to-firm trade is essential for economic activity, yet little is known about how well firms find and connect with suppliers and clients. Barriers in the search process can prevent firms from finding potential partners, and barriers to starting a relationship can hinder connections even when a suitable candidate is identified. As a result, firms may end up with too few partners, or the wrong partners, limiting their growth and the broader potential for industrial development.

While these challenges seem important, the evidence on how firms access one another is thin. Recent work has evaluated interventions that create firm-to-firm connections as a byproduct of infrastructure developments such as mobile phone networks or high-speed trains (Jensen and Miller 2018; Bernard, Moxnes and Saito 2019), or that create cross-country connections (Atkin, Khandelwal, and Osman 2017). However, there is little evidence on initiatives aimed directly at fostering connections, especially between firms located in close proximity. Furthermore, we lack understanding of how improved access between firms reshapes industry outcomes—whether by altering network structures, promoting industrial upgrading, or generating welfare benefits. Finally, the specific barriers that prevent nearby firms from forming productive partnerships remain underexplored.

The study: Making referrals of business partners

To address these challenges, we implemented an intervention in 2021, in which we referred suppliers and clients to each other in the industry producing the Chinese brush pen (Cai, Lin, and Szeidl 2024). Our study focused on a renowned production hub in Jiangxi Province, which dominates the brush pen market in China. The supply chain for brush pen comprises two main layers: (1) suppliers who produce intermediate inputs like the brush head and the handle, and (2) clients who assemble and sell the final product. During our initial data collection, we surveyed most firms in this location—about 800 total—and gathered information on both firm performance and the supplier-client network.

To generate effective referrals, we utilized the baseline network data, guided by the principle that a supplier (firm A) would likely be a good match for a client (firm B) if A already supplied a close competitor of B, or if B was already purchasing from a close competitor of A. We termed such referrals "screened." We then introduced four treatment arms:

1. Screened subsidy: Screened referrals were made, accompanied by a subsidy for the first transaction.

2. Unscreened subsidy: Referrals were randomly chosen from the pool of potential partners, with a subsidy for the first transaction.

3. Screened information: Screened referrals were made, but no subsidy was offered. This arm was expected not to lead to take-up, which was confirmed in the data.

4. Control: We constructed but did not make referrals. We created control arms for both screened and unscreened referrals.

To measure impacts on firm performance, we randomized both suppliers and clients into treatment and control groups. Subsidized referrals were made only between treated suppliers and treated clients. This design enabled us to compare treated and untreated firms and evaluate the firm-level effects of the referrals.

Subsidized referrals rewired the supplier-client network

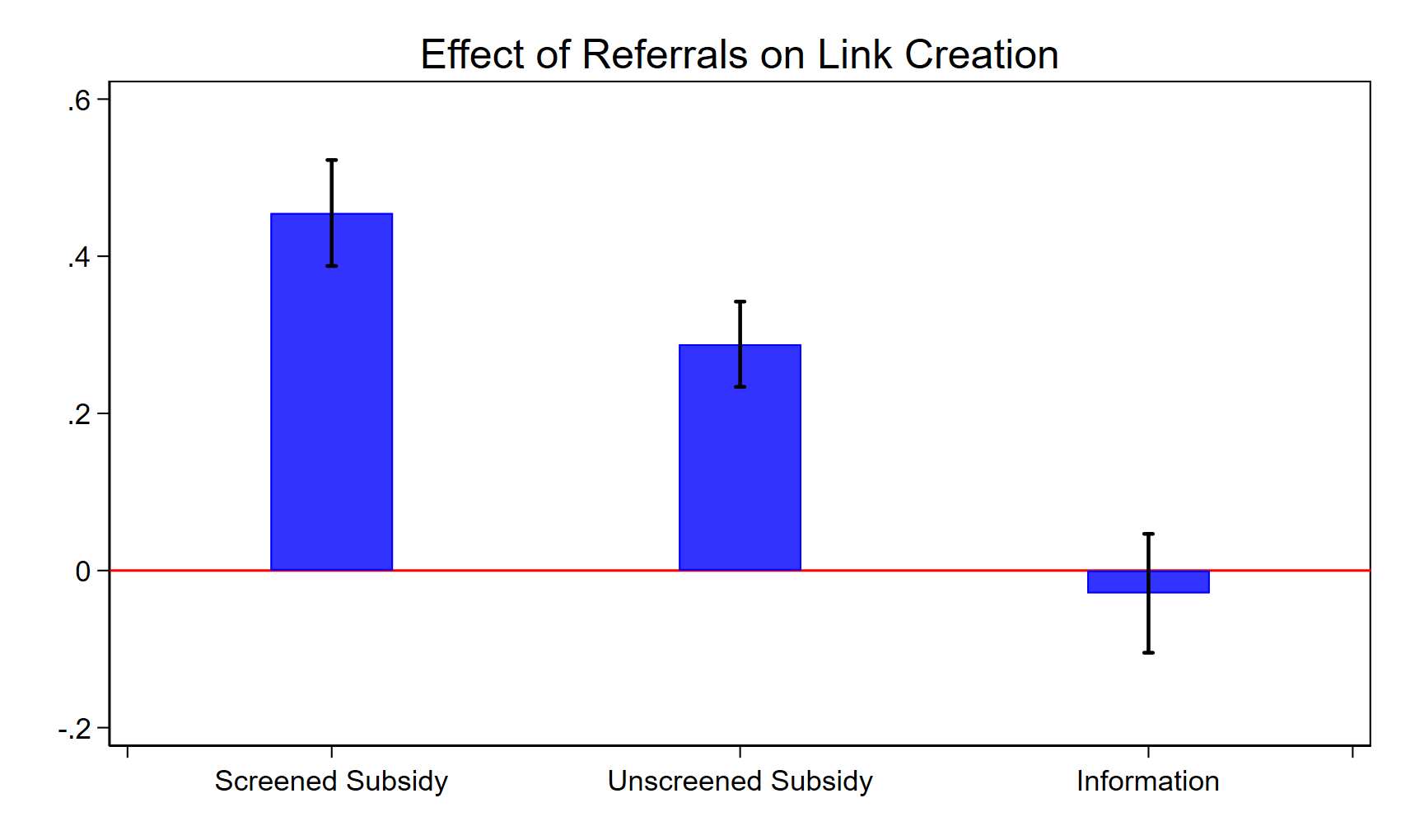

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of the referral treatment on the creation of new business links, measured with new transactions after the subsidy period ended. The results show that the screened subsidy significantly increased the likelihood of subsequent transactions, by about 46 percentage points. The unscreened subsidy also had a positive effect, though smaller, increasing the probability by 29 percentage points. In contrast, the pure information referral had no detectable impact. (In these comparisons the control group is always analogous referrals we constructed but did not make.) These findings suggest that frictions prevented firms from doing business with potential partners, and that these frictions are not solely due to a lack of information about the identity of partners.

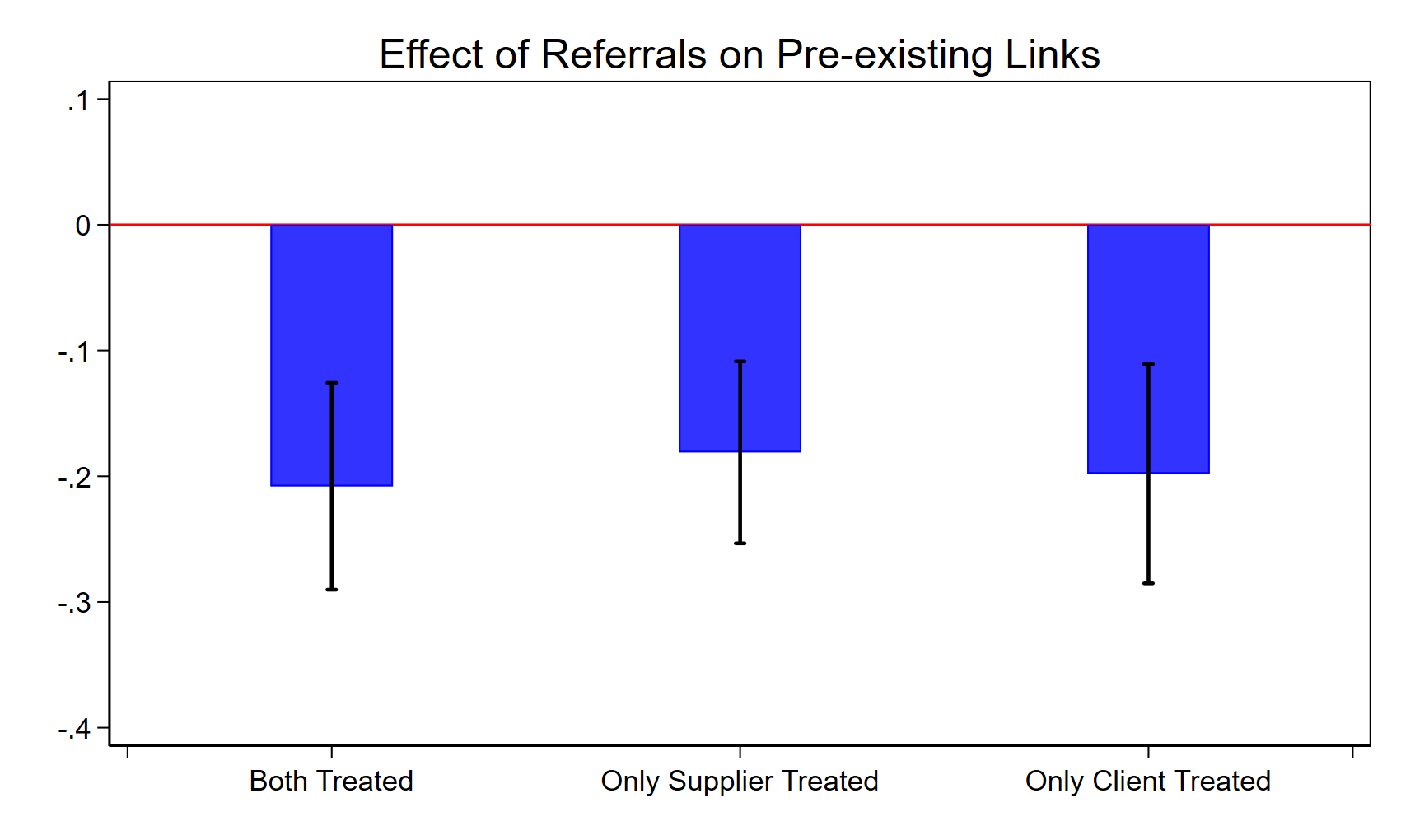

The creation of new partnerships through referrals may have crowded out some existing links. Figure 2 confirms this effect. Pre-existing links were about 20 percentage points less likely to be maintained when either the supplier or the client (or both) were treated. Thus, the treatment led to a reallocation of business links, with firms shifting toward referrals at the expense of some existing partners. In summary, the referrals caused a rewiring of the business network, generating both new connections and a redistribution of existing ones.

Effects of referrals on firm performance

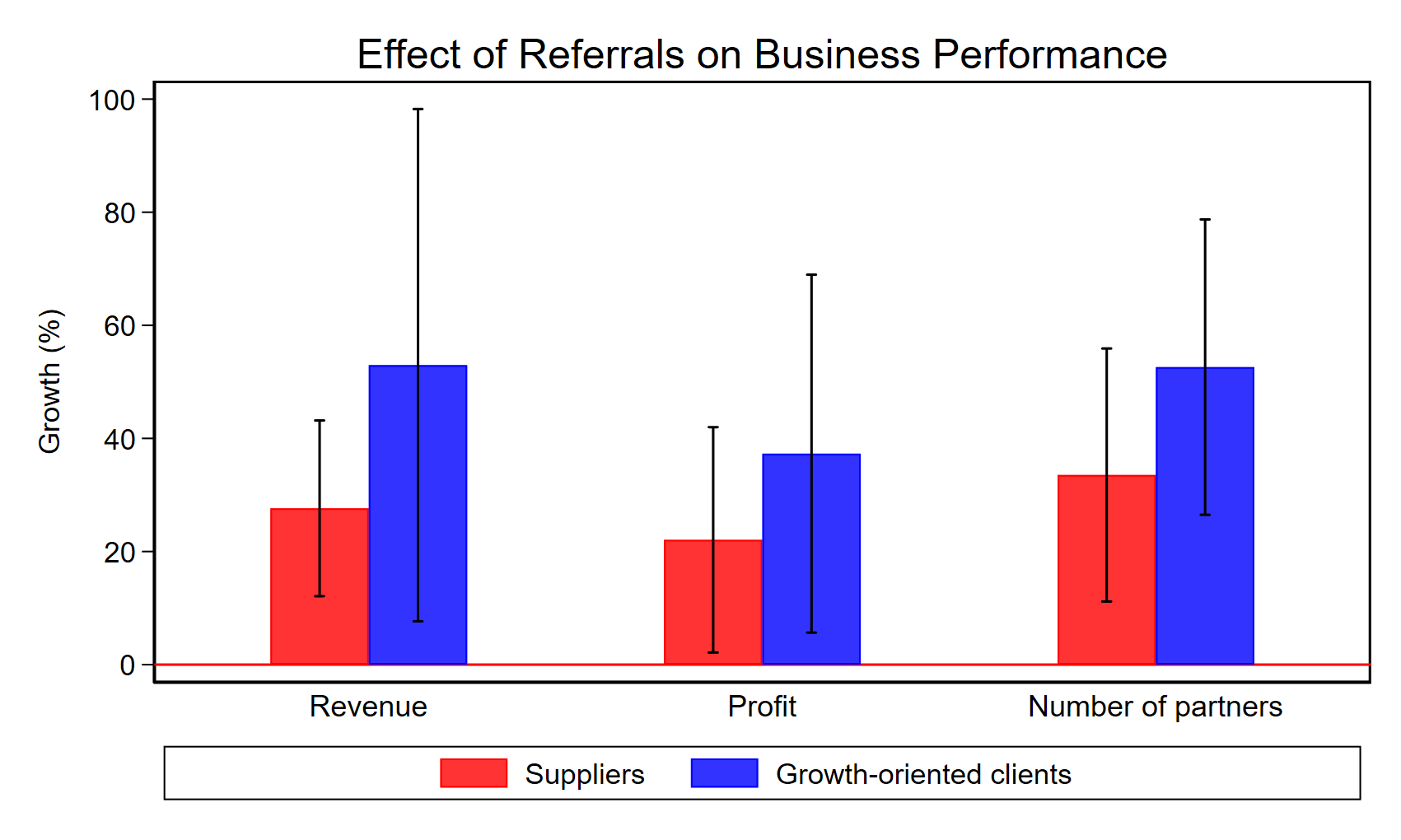

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of the referral treatment on firm performance. We show impacts for suppliers and for a subgroup of clients who report themselves to be growth-oriented at baseline, indicating that these clients have free capacity to expand. We do this because we do not find significant effects for the full sample of clients.

For suppliers, the results indicate significant improvements in revenue, profit, and the number of new partnerships. Among growth-oriented clients, we observe similarly large and significant gains across these same outcomes. For non-growth-oriented clients we find insignificant effects on all three outcomes (not shown in the figure). These findings suggest that improving firm-to-firm access can lead to substantial benefits by enabling suppliers, as well as clients with free capacity, to expand their operations.

Intermediate outcomes and mechanisms

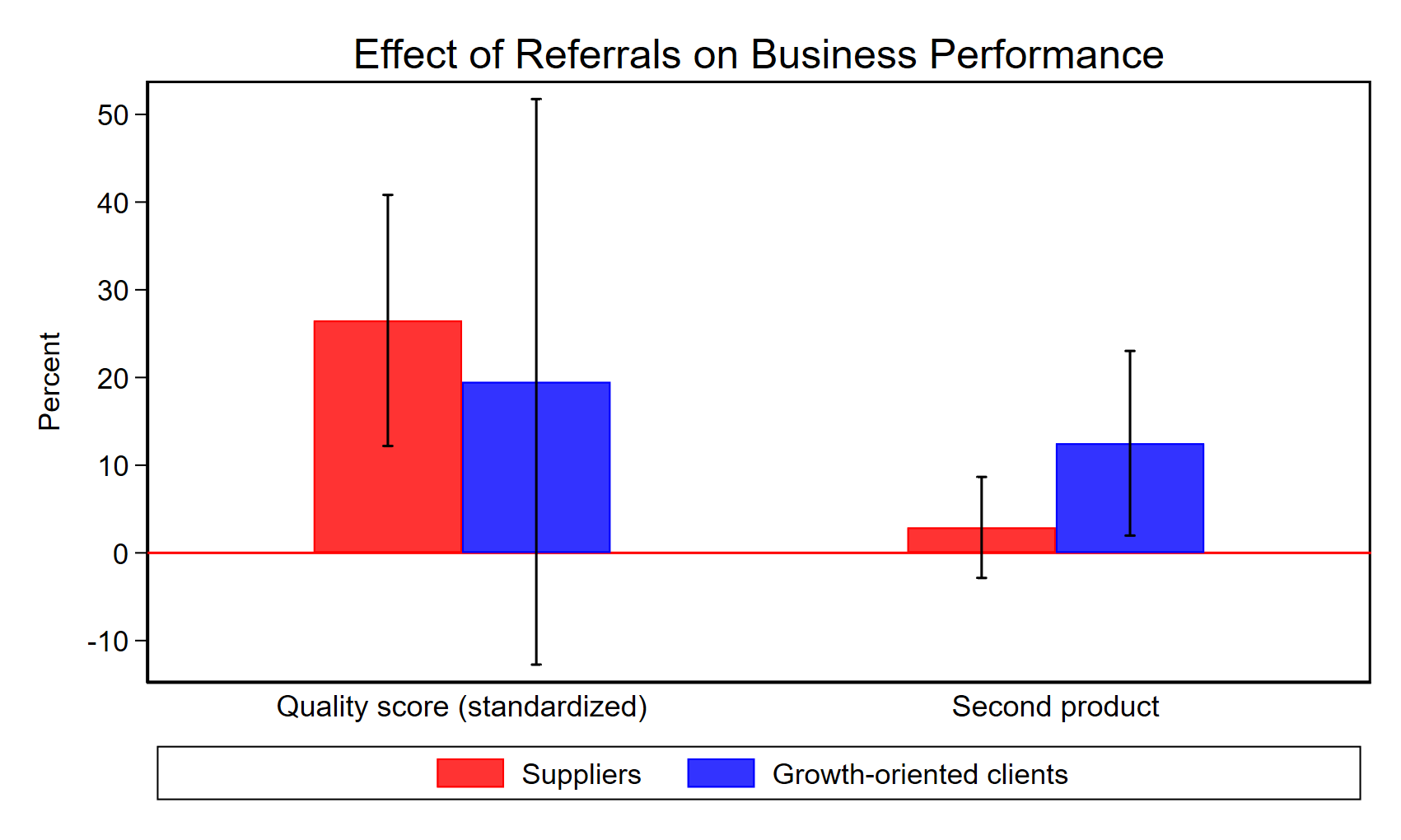

How did the referrals enable firms to expand their business? To better understand the underlying mechanisms, we explore impacts on two sets of intermediate outcomes. First, in Figure 4 we show impacts on supplier and growth-oriented client product quality and variety and quality. For suppliers, we see a significant increase in product quality, as evaluated by independent experts. For growth-oriented clients we see a significant increase in the firm offering a second product. In this industry, second products are generally of higher quality. Thus, an intuitive narrative is that treated clients used the intermediate input coming from their new suppliers to expand the production of their higher-quality second product, which required treated suppliers to improve quality. In this narrative, suppliers and clients upgrade in a complementary fashion: suppliers increase product quality because clients expand product variety, and clients expand product variety because suppliers increase product quality. Thus, our findings support the importance of a quality complementarity between suppliers and clients in production networks.

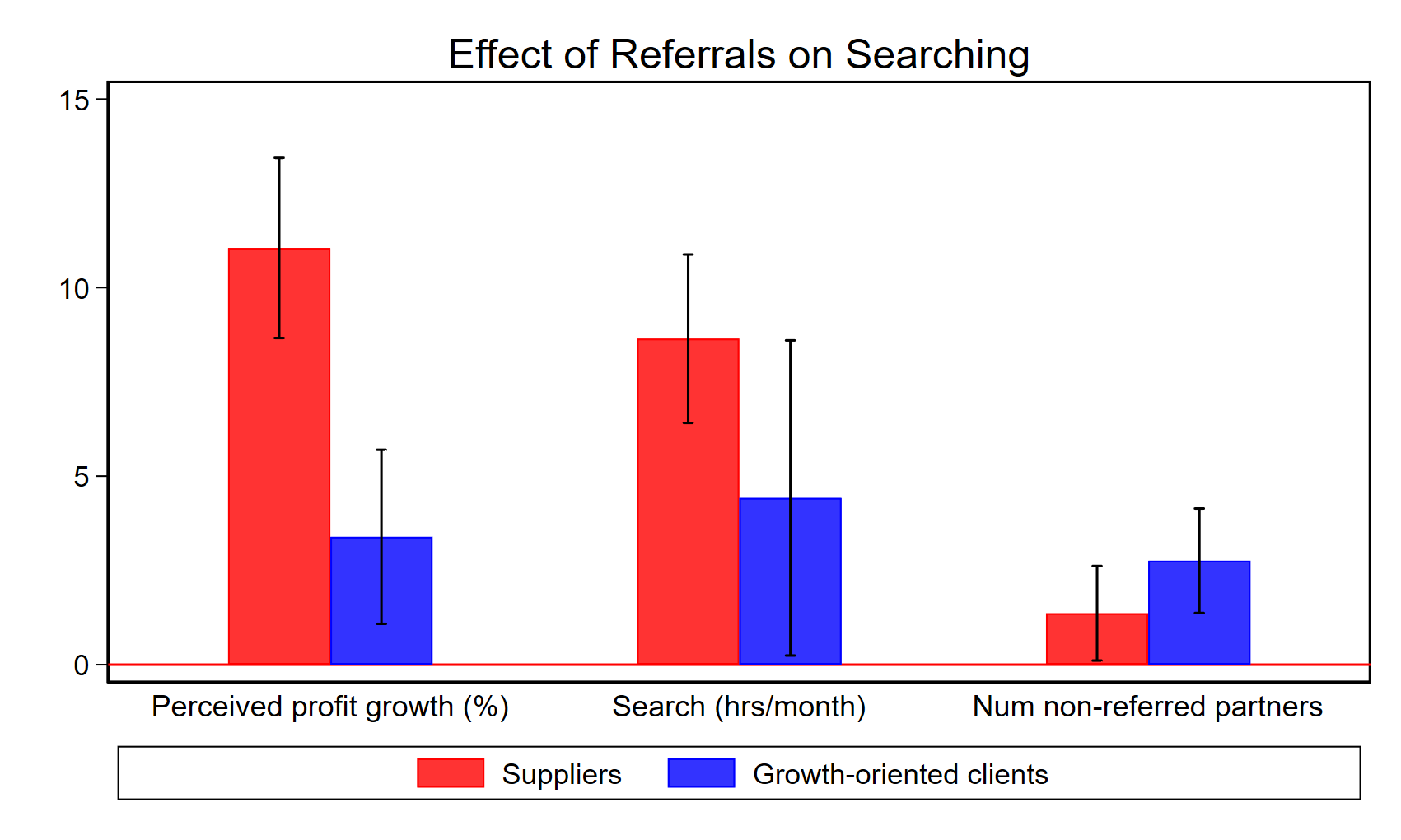

We also found significant effects on firms’ search activities. Figure 5 shows that in response to the referrals, firms increased their beliefs about the benefits of search, allocated more time to search, and established additional new partnerships beyond the ones we referred to them. These results provide direct evidence that firms absent our intervention under-searched because they undervalued new partners.

It follows that our results identify a new firm-to-firm partnering friction, the undervaluation of potential partners. Undervaluation can act as a search friction by reducing the incentives to search, as we have just seen. It can also act as a matching friction by reducing the incentives to engage even when a partner is available, helping to explain why firms receiving the information referrals did not take up.

Policy impact

Our results suggest that matchmaking interventions, such as trade fairs or B2B transaction platforms, can generate meaningful gains in business performance.

Conclusion

We found evidence on the narrative that (1) firms underestimate the value of partners and therefore under-search; (2) referrals create new partnerships and crowd out existing ones; (3) referrals greatly improve firm performance, by inducing complementary upgrading in suppliers and clients and by increasing beliefs in the value of partnerships and search effort.

These results are obtained in a setting with substantial product differentiation, which makes the choice of partners important. Thus, the external validity of our results is highest in industries that feature product differentiation. Our setting has firms in close proximity and features a centralized market. These facts suggest that in settings where firms are more dispersed and markets less centralized, firm-to-firm access frictions may be even larger.

References

Atkin, David, Amit K. Khandelwal, and Adam Osman. 2017. “Exporting and Firm Performance: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (2): 551–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx002.

Bernard, Andrew B., Andreas Moxnes, and Yukiko U. Saito. 2019. “Production Networks, Geography, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Political Economy 127 (2): 639–88. https://doi.org/10.1086/700764.

Cai, Jing, Wei Lin, and Adam Szeidl. 2024. “Firm-to-Firm Referrals.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 33082. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33082.

Jensen, Robert, and Nolan H. Miller. 2018. “Market Integration, Demand, and the Growth of Firms: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in India.” American Economic Review 108 (12): 3583–3625. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161965.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email