Digital Distractions with Peer Influence: The Impact of Mobile App Usage on Academic and Labor Market Outcomes

We present the first comprehensive evidence of how app usage affects academic performance and early career outcomes. App usage is contagious: a one standard deviation (around 3.5 hours per day) increase in roommates’ app usage raises an individual’s own app usage by 5.8%, with substantial heterogeneity across students. A one standard deviation increase in app usage reduces GPAs by 36.2% of a within-cohort-major standard deviation and lowers wages by 2.3%. The effect of roommates’ app usage is over half the size of an individual’s own usage effect. High-frequency GPS data reveal that high app usage crowds out time in study halls and increases late arrivals at and absences from lectures.

Data Use Clarification: This research has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Social Science and Humanities at Jinan University (IRB No. A2408001-038). All data sets used in the analysis are stored and processed in a fully secured data lab (offline without USB access) in China by the data provider. The data are processed under strict rules to protect individual privacy. We write executable files that are executed by data lab staff. None of the authors have access to any form of the raw data.

Mobile apps have brought significant convenience to our daily lives, yet concerns are growing about their overuse. There is mounting evidence across the globe that teenagers and young adults are especially prone to excessive and sometimes inappropriate use of mobile apps. In a 2018 China survey, 77.5% of college students admitted to playing mobile games during class (with 35% doing so frequently); a 2019 UK study found that 39% of young adults reported smartphone addiction (Sohn et al. 2021). In the US, over 70% of high school teachers in a 2023 survey identified phone distractions as a significant issue in the classroom (Lin, Parker, and Horowitz 2024). In a 2023 OECD study, 65% of students from 81 countries reported being distracted by their own usage of digital devices during math lessons, while 59% reported distractions from other students’ use of digital devices in those lessons (OECD 2023). That is, digital distractions can be detrimental not only to individuals themselves, but also to their peers (Avdeev et al. 2024).

These concerns have triggered policies aimed at curbing mobile app use. In September 2019, the Chinese government introduced a game-hour restriction for minors. As of August 2024, eleven US states have enacted or considered policies restricting phone use during school hours.

Despite the widespread concern about app overuse and government policy responses, little rigorous research has been conducted on the long-term implications of app usage on human capital development and the aggregate labor market. Our recent study (2024) takes a step toward addressing this issue and presents, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive evidence of how app usage by individuals and their peers affects academic performance, physical well-being, and early career outcomes.

Empirical investigations of how app usage affects human capital accumulation face three key challenges. First, researchers lack suitable data that links phone usage with outcome measures. We overcome this obstacle by exploiting two unique datasets: the first from a leading Chinese cellular service provider that contains comprehensive mobile phone records of all subscribers in a populous Chinese province, and the second from a university in the same province that contains administrative records of students' demographic and academic backgrounds, in-college performance, and job market outcomes upon graduation for several cohorts.

The second challenge involves the typical complications encountered in the empirical estimation of peer effects (Manski 1993; Bramoullé, Djebbari, and Fortin 2020). We recover peer effects in two steps. First, by leveraging the university’s random dorm room assignment policy and focusing on a narrowly defined peer group—roommates—we provide causal estimates of the “reduced-form” peer effects that are functions of both behavioral spillover and contextual peer effects. Second, we disentangle these two types of peer effects using quasi-experimental policy variations as a result of the 2019 minors’ game restriction policy that impacted peers’ peers.

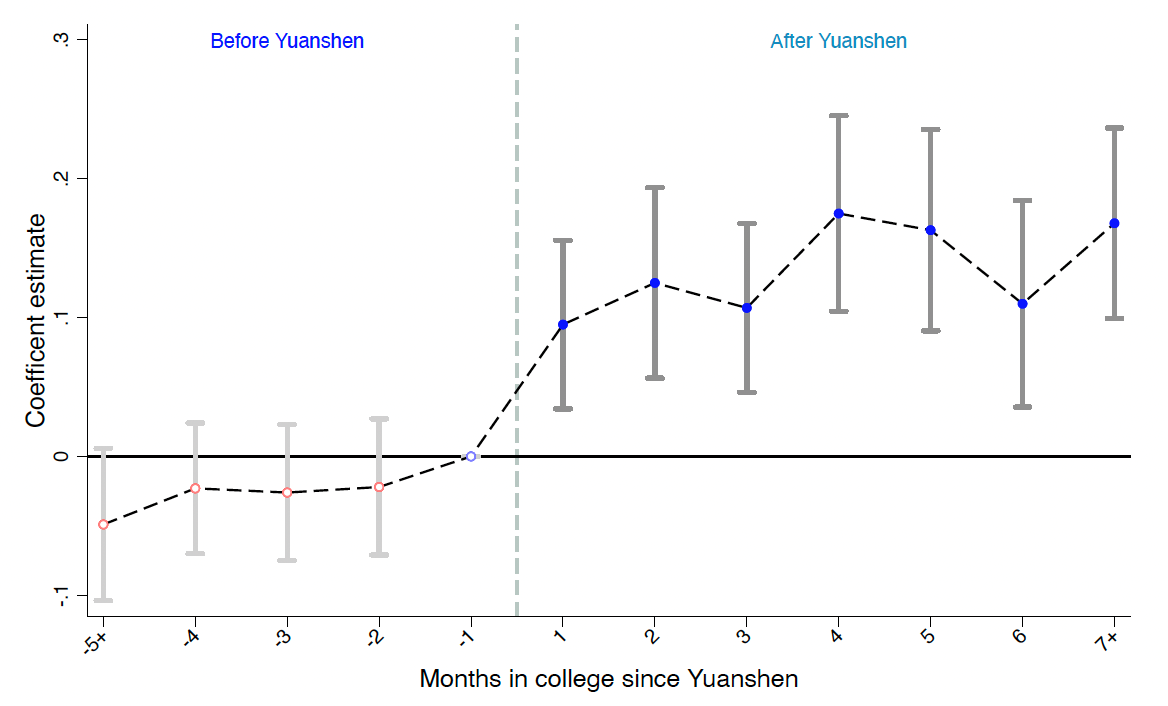

The third challenge arises from the endogeneity of mobile app usage. To address this, we use two sets of instruments. The first exploits the 2019 minors’ game restriction mentioned earlier, which indirectly affected students in our study through their underage friends. The second set of instruments exploits the launch of the blockbuster game Yuánshén midway through our sample period. We interact Yuánshén’s release date with students' pre-college app usage to construct a shift-share type of instruments. Figure 1, Panel (a) shows that after the release of Yuánshén, the increase in app usage depends significantly on one’s pre-college app usage. Panel (b) indicates that upon the introduction of the minors’ game restriction, students with more underage pre-college friends reduced app usage significantly more than those with fewer underage friends.

Figure 1: Effect of Yuánshén and minors’ game restriction policy on game app time

(a) Effect of Yuánshén on game app time

(b) Effect of minors’ game restriction policy on game app time

Notes: These graphs present the event study coefficients for the interaction between Yuánshén *pre-college game app usage, Panel (a), and coefficients for the interaction between minors’ game restriction policy*the number of underage pre-college friends, Panel (b), showing the impact of the two shocks on game app time. The regression follows Equation (8), except that the dependent variable is game app usage. The coefficient for one month prior to each shock is normalized to zero. The dots are point estimates, and the solid grey lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

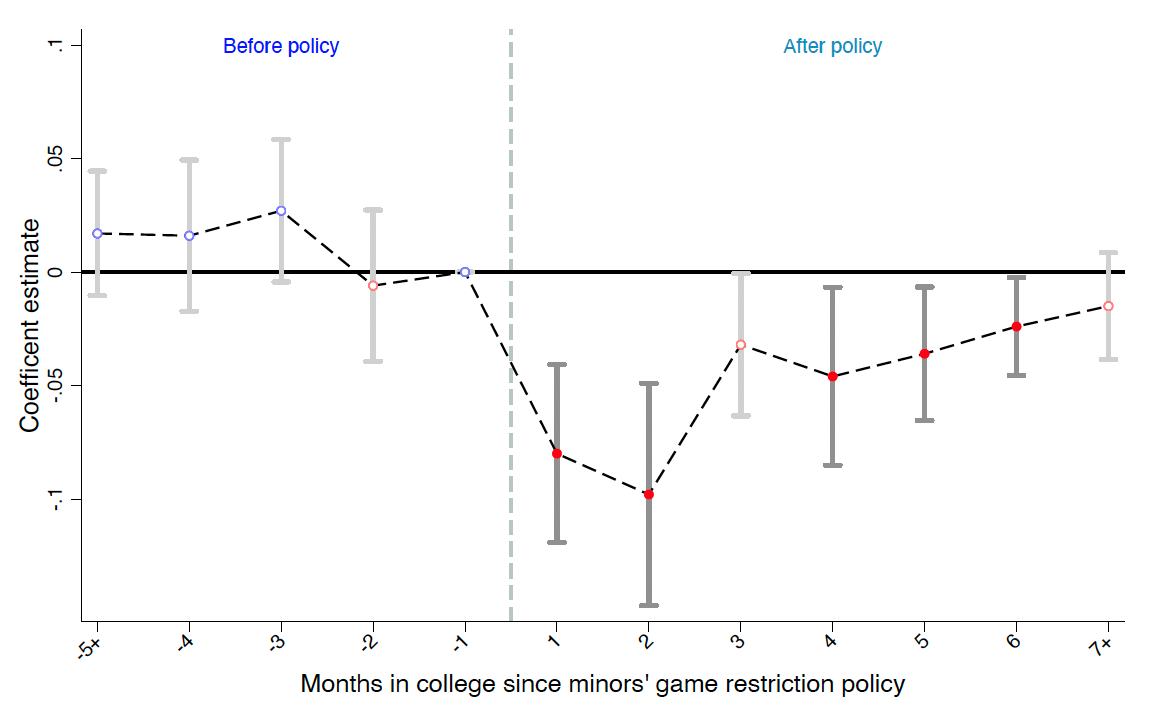

Our analyses yield a rich set of findings. First, mobile app usage is indeed contagious. As shown in Figure 2, there is a strong and tight correlation between individuals’ app usage and that by their roommates. Controlling for student fixed effects and utilizing the panel data structure, our IV estimates suggest that a one standard deviation increase in roommates’ in-college app usage (around 3.5 hours per day) increases an individual’s own app usage by 5.8%. This behavioral spillover effect dominates the contextual peer effect. Despite the extensive literature on peer effects, this analysis provides, to our knowledge, the first empirical estimates that distinguish between behavioral spillover effects and contextual peer effects.

Figure 2: Contemporaneous correlation in mobile app usage

Notes: These graphs present individuals’ residualized monthly mobile app time (in logarithm) at college against the monthly app time of their roommates. The solid line shows the linear fit estimated on the underlying microdata using OLS.

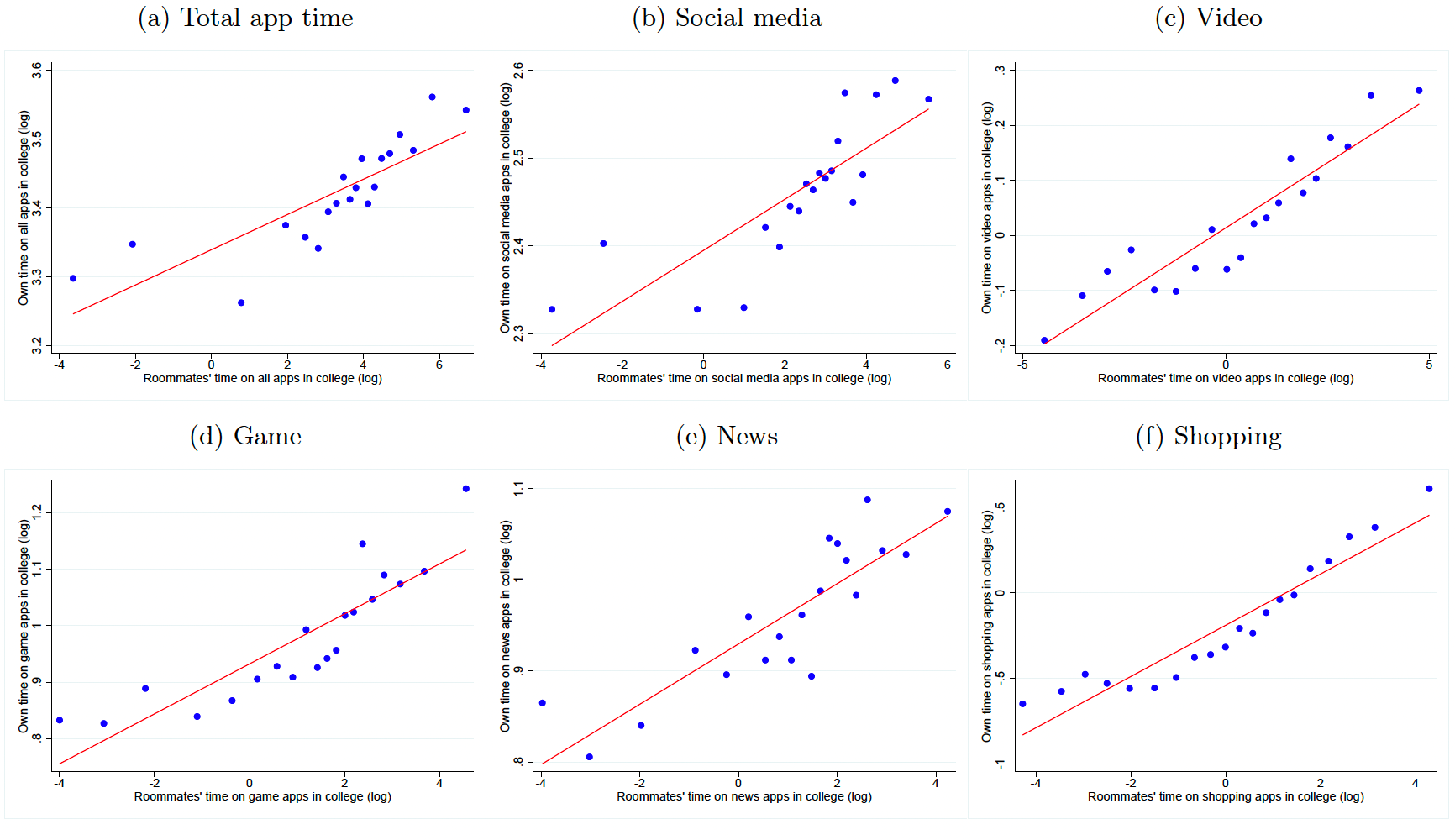

Second, mobile app usage negatively affects GPAs. Different from the existing literature, we allow roommates’ app usage to affect academic outcomes both indirectly via behavioral spillovers and directly. Controlling for student fixed effects, our IV estimates indicate that a one standard deviation increase in an individual’s app usage reduces their GPA for required courses in the same semester by 36.2% of a within-cohort-major standard deviation. Remarkably, a one standard deviation increase in roommates’ app usage directly lowers an individual’s GPA by 20.6% of a standard deviation. Combining the direct and the indirect (via behavioral spillover) peer effects, a one standard deviation increase in roommates' app usage results in a 22.7% standard deviation reduction in an individual’s GPA (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Effect of mobile app usage on GPA

(a) GPA vs. own mobile app usage (b) GPA vs. roommates’ mobile app usage

Notes: These graphs present the residualized relationship between GPA and individual app usage (in logarithm) during college, Panel (a), and that between GPA and average roommates' app time (in logarithm) during college, Panel (b). We control for class-semester (with class a triplet of cohort, major, and administrative unit, consisting of 20 to 50 students) and student fixed effects in each graph. The solid line represents the linear fit estimated from the underlying microdata using OLS.

Third, app usage’s effect on physical health, as proxied by physical education (PE) scores, is three times greater than its effect on GPAs of required courses. In contrast, roommates’ app usage has no direct effect on PE scores, likely because disruptions from gaming are less relevant for outdoor activities.

Fourth, utilizing the rare linkage of app usage with labor market outcomes upon graduation, our IV estimates imply that a one standard deviation increase in own (roommates’) in-college app usage reduces wage upon graduation by 2.3% (0.9%), or 12.1% (4.7%) of a within-cohort-major standard deviation.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that if China’s minors’ game restriction policy were extended to college students, i.e., capping game time to three hours per week, students’ initial wages would increase by 0.9%, equivalent to half of the wage premium from an extra year of work experience in developing countries (Lagakos et al. 2019).

Fifth, there is considerable heterogeneity in peer effects and the effects of app usage on outcomes. Students from wealthier families and those who were heavier app users before college experience much stronger peer behavioral spillover effects. These students also suffer more severe negative impacts from app usage on their GPAs, though not more negative impacts on wage outcomes.

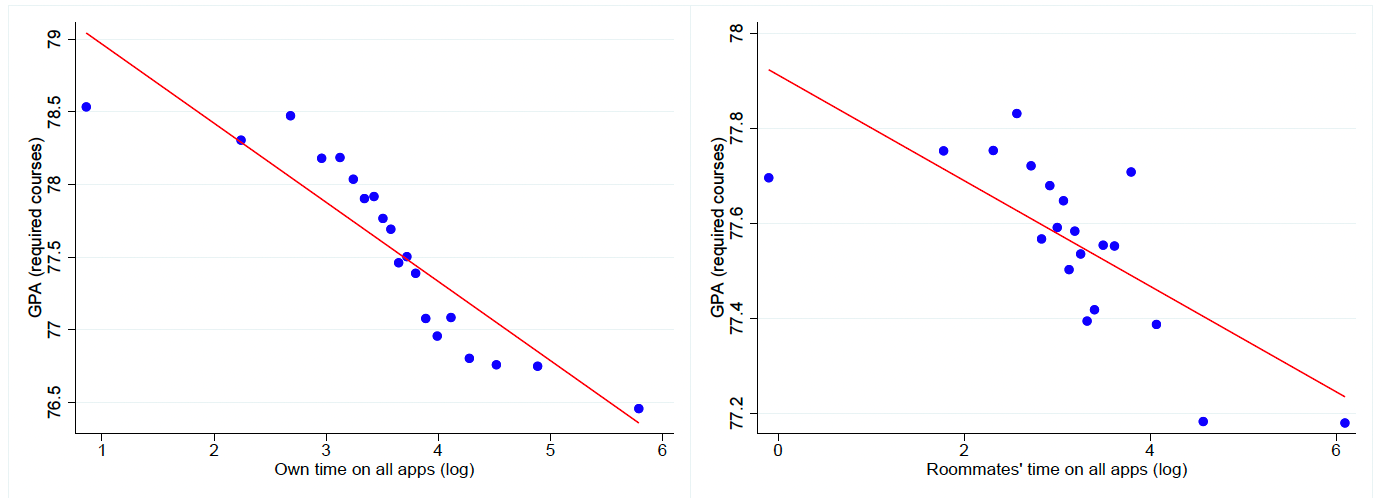

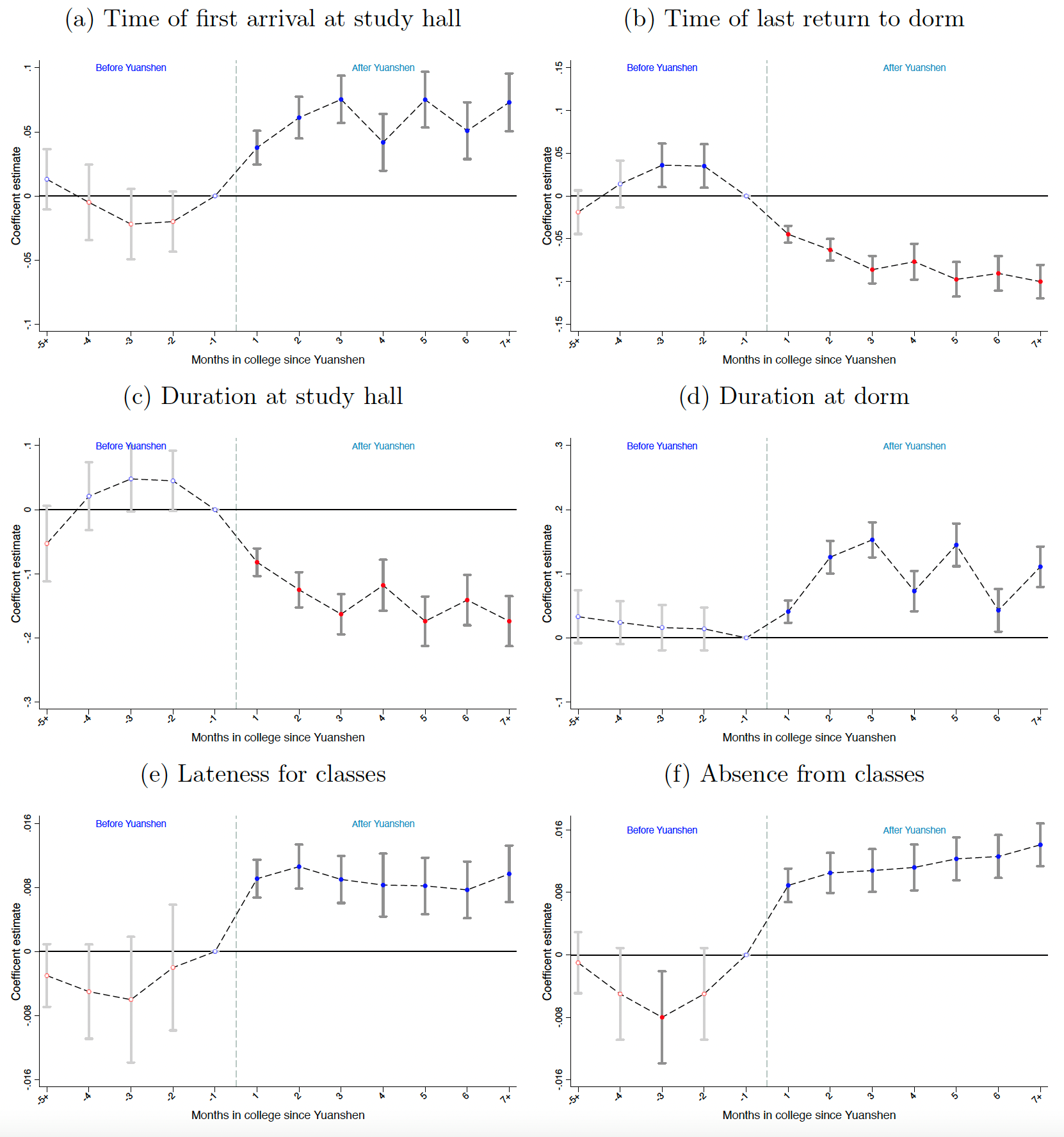

Finally, we present two sets of evidence to shed light on the mechanisms underlying these findings. Our first evidence comes from high-frequency location data collected by mobile phones’ GPS that allow us to precisely measure the extensive-margin time allocation. We find that app usage reduces (increases) time spent in study halls (dorms) and increases late arrivals at and absences from lectures (Figure 4). The second set of evidence comes from our online surveys, where heavier app users report poorer physical and mental health, submit fewer job applications, and are less satisfied with their job offers, aligning with our findings above. Notably, heavier users are more likely to recognize the addictive nature of gaming, suggesting a self-control problem rather than a lack of awareness.

Figure 4: Effect of Yuánshén on on-time performance

Notes: These graphs display the event study showing the impact of the Yuánshén shock on on-time performance metrics. The outcomes in Panels (a)-(f) are time of first arrival at the study hall (in hourly format), time of last return to the dorm (in hourly format), duration at the study hall in hours, duration at the dorm in hours, lateness by at least ten minutes for major-required classes, and absences from major-required classes, respectively. The coefficient for one month prior to the Yuánshén shock is normalized to zero. The dots are point estimates, and the solid gray lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. Yuánshén increases app usage and leads to reduced time in study halls and more lateness and absences from required courses.

Our study documents economically and statistically significant negative consequences of app usage, not only for individuals, but also for their peers. There are several fruitful directions for future research, including deeper investigation into the underlying mechanisms through which digital distractions influence individuals’ and peers’ outcomes, and the study of how digital distractions may affect the aggregate economy.

References

Avdeev, Stanislav, Nadine Ketel, Hessel Oosterbeek, and Bas van der Klaauw. 2024. “Peer Effects in Field of Study Choices.” VoxEU, April 13. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/peer-effects-field-study-choices.

Barwick, Panle Jia, Siyu Chen, Chao Fu, and Teng Li. 2024. “Digital Distractions with Peer Influence: The Impact of Mobile App Usage on Academic and Labor Market Outcomes.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 33054. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33054.

Bramoullé, Yann, Habiba Djebbari, and Bernard Fortin. 2020. “Peer Effects in Networks: A Survey.” Annual Review of Economics 12 (12): 603–29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-020320-033926.

China Daily. 2018. “Students Who Play Mobile Games Are Wasting Their Time.” China Daily, January 10, 2018. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201801/10/WS5a55539ea3102e5b17371b6f.html.

Lagakos, David, Benjamin Moll, Tommaso Porzio, Nancy Qian, and Todd Schoellman. 2019. “Life Cycle Wage Growth across Countries.” Journal of Political Economy 126 (2): 797–849. https://doi.org/10.1086/696225.

Lin, Luona, Kim Parker, and Juliana Horowitz. 2024. “What’s It Like to Be a Teacher in America Today?” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/04/ST_24.04.04_teacher-survey_report.pdf.

Manski, Charles F. 1993. “Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem.” Review of Economic Studies 60 (3): 531–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/2298123.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2023. “PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education.” OECD, December 5, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i_53f23881-en.html.

Singer, Natasha. 2024. “Why Schools Are Racing to Ban Student Phones.” New York Times, August 11, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/11/technology/school-phone-bans-indiana-louisiana.html.

Sohn, Sei Yon, Lauren Krasnoff, Philippa Rees, Nicola J. Kalk, and Ben Carter. 2021. “The Association Between Smartphone Addiction and Sleep: A UK Cross-Sectional Study of Young Adults.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 629407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.629407.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email