Overpricing in Municipal Bond Markets and the Unintended Consequences of Regulatory Measures: Evidence from China

Chinese municipal bonds are considerably overpriced in the primary market, leading regulators to set a lower bound on the issuance yield spread. This paper investigates the underlying reasons for this overpricing and evaluates the effects of implementing restrictions on yield spreads. Our findings indicate that underwriters may inflate prices to receive undisclosed benefits from local governments, such as local treasury cash deposits. We further show that the lower bounds severely impede price discovery in the primary municipal bond market. Even bonds not restricted by the lower limit are priced at the reference spread, exacerbating overpricing of riskier bonds. Local governments exploit these fixed prices by increasing the bond issuance amount and extending bond maturity. Our findings suggest that regulatory interference in pricing can have unintended consequences for pricing efficiency and that attempts to rectify mispricing may result in even more severe mispricing.

China’s municipal bond market has soared to become the world’s largest, driven by reforms to facilitate local government financing and modernize the fiscal system. Municipal bonds, specifically those directly issued by local governments, were first introduced after Budget Law amendments allowed direct issuance in 2014, to replace local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) backed by implicit guarantees. Aiming for transparency, Guofa No. 43 (2014) promoted “opening the front door and closing the back door,” legitimizing debt issuance channels while curtailing opaque LGFV borrowing. However, a critical issue emerged: overpricing in the primary market, with many municipal bonds issued at yield-to-maturity lower than treasury bonds of the same maturities, indicating an obvious price distortion.

To rectify this overpricing, Chinese regulatory authorities implemented several measures, the most direct being the imposition of a lower bound on the yield spread at issuance. In August 2018, the Ministry of Finance mandated that the yield spread of municipal bonds should be at least 40 basis points (bps) higher than the average treasury bond rate of the same maturity five days before their issuance. This restriction was adjusted in January 2019 to require a minimum spread of 25 bps. These pricing restrictions quickly began to influence municipal bond pricing in the primary market.

We investigate the factors behind the overpricing of municipal bonds in China and the regulatory attempts to curb it. Growing attention has been devoted to pricing issues within the Chinese bond market (Liu, Lyu, and Yu 2017; Chen, He, and Liu 2020; Ding, Xiong, and Zhang 2022; Jin, Wang, and Zhang 2023; Ang, Bai, and Zhou 2023; Chen et al. 2023; Geng and Pan 2024), in this paper (Liu, Liu, Liu, and Zhu 2024), we delve into the municipal bond market and expand this line of research by elucidating the drivers of overpricing in this specific sector. Amid the focus on stock markets in discussions about price intervention within the academic and policy realms (Miller 1977; Harrison and Kreps 1978; Kim and Rhee 1997; Chan, Kim, and Rhee 2005; Bris, Goetzmann, and Zhu 2007; Chang, Cheng, and Yu 2007; Ritter 2011; Saffi and Sigurdsson 2011; Beber and Pagano 2013; Chang, Luo, and Ren 2014; Chen et al. 2018; Qian, Ritter, and Shao 2024), our study examines the impact of pricing restrictions on municipal bonds, offering fresh insights into how regulatory measures intended to correct distortions might inadvertently exacerbate inefficiencies.

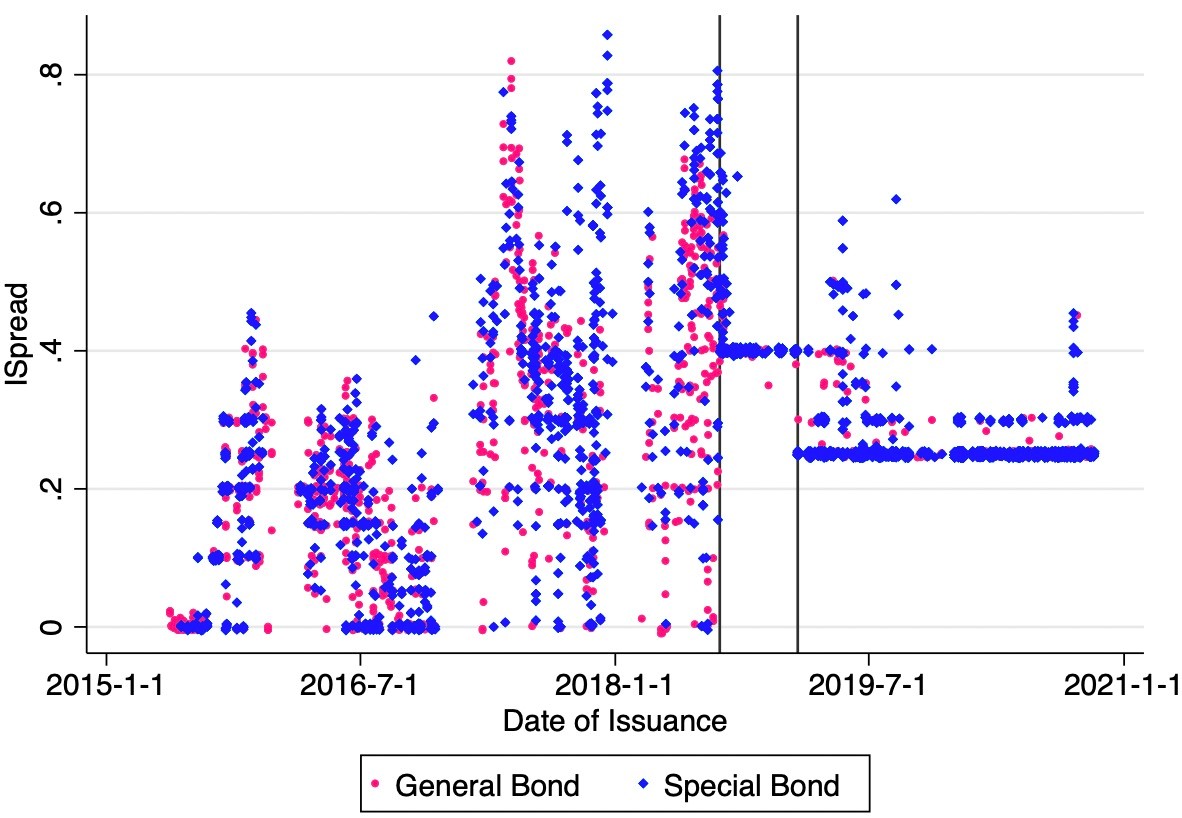

Figure 1 illustrates the yield spread (i.e., issuance spread) of municipal bonds relative to the five-day average of treasury bond rates with the same maturity since 2015. A significant shift in the issuance spreads of municipal bonds is observed following the implementation of pricing restrictions. Prior to the 2018 regulation, issuance spreads showed considerable variation, ranging from around 0 to over 80 bps. After 2018, with the introduction of the 40 bps lower bound, spreads converged tightly around this regulatory threshold. Surprisingly, not only did bonds with spreads below 40 bps diminish from the market, but those exceeding this limit also saw a significant decline. Subsequently, when the lower bound was adjusted to 25 bps in 2019, spreads further converged around the new 25-bps limit, with few bonds surpassing this threshold.

Figure 1. Issuance spreads of municipal bonds over time

Notes: The figure displays the issuance spread of municipal bonds compared to the five-day average treasury bond rates with the same maturity since 2015. Two types of municipal bonds, general and special, are distinguished by color: general bonds are shown in red while special bonds are in blue. The horizontal axis marks the issuance dates of municipal bonds, and the vertical axis represents the issuance spread (%). The two vertical markers signify the enforcement dates of pricing restrictions (August 14, 2018 and January 29, 2019).

Core Findings

1. Underwriters and Local Governments’ “Give-and-Take” Relationship

One of the primary drivers of overpricing in China’s municipal bond market is the relationship between bond underwriters and local governments. Underwriters inflate bond prices to secure indirect benefits from local governments, such as access to local treasury deposits. In regions where underwriters obtain larger shares of local treasury cash and where state-owned enterprises exert greater influence over the local economy, municipal bonds are issued at lower spreads (i.e., higher prices). This mutually beneficial relationship involves underwriters accepting financial losses in the bond market in exchange for potential favors from local government, such as deposit privileges.

2. Unintended Consequences of Pricing Restrictions

The introduction of pricing restrictions aimed at curbing this practice had several unintended effects.

Price convergence: Bonds with varying levels of risk are now priced similarly due to the imposed floors. The riskier bonds, which should have been priced with higher yield spreads, are instead anchored to the regulatory threshold, resulting in uniform pricing that does not reflect underlying risks.

Worsening overpricing for riskier bonds: While the restrictions reduced overpricing for less risky bonds, they exacerbated it for riskier bonds. These bonds, which are inherently more volatile, saw their issuance spreads converge toward the floor, leading to greater overpricing relative to their risk profile.

Distortion of market efficiency: The pricing restrictions impaired price discovery, a crucial function of financial markets. Instead of reflecting the risks associated with different bonds, prices became pegged to regulatory limits, undermining the bond market's ability to allocate capital efficiently.

3. Impact on Non-Bank Underwriters and Issuance Decisions

Following the implementation of pricing restrictions, non-bank financial institutions (e.g., securities firms) increased their participation in underwriting bonds that exhibited lower levels of overpricing. This shift suggests that non-bank underwriters, who do not benefit from the deposit arrangements available to banks, became more active in less risky segments of the market where pricing was less distorted. On the other hand, in response to pricing inefficiencies, local governments extended the maturity of municipal bonds newly issued, exploiting the mispricing created by regulatory floors to secure more favorable terms for their debt.

Our findings contribute to the broader debate on the marketization of municipal bonds in emerging economies and provide insights into the risks associated with regulatory interventions that prioritize short-term corrective measures over long-term market efficiency.

Policy Implications

Our findings have broader implications for regulatory policies in bond markets, particularly in emerging economies. The evidence suggests that, although they were intended to mitigate mispricing, pricing restrictions paradoxically hinder market efficiency. Price discovery—where bond prices reflect the true risks associated with the issuer—is essential for the effective functioning of any financial market. However, regulatory interventions that disrupt this process can inadvertently perpetuate greater inefficiencies, yielding suboptimal results for investors and local governments alike.

Furthermore, our study underscores the imperative to tackle the root causes of overpricing, rather than resorting to superficial regulatory measures. In this scenario, the intertwined relationships between underwriters and local governments, which lead to misaligned incentives, should be decoupled to reestablish a fair pricing mechanism within the municipal bond market. Without addressing these structural imbalances, any regulatory efforts to rectify overpricing are likely to induce further distortions.

China’s regulatory authorities have indeed embarked on several noteworthy initiatives to bolster the overall governance and risk management of local government debt. Their dedication to improving the municipal bond market is admirable, yet caution is advisable when enforcing price interventions. While these administrative restrictions are meant to address mispricing, they may inadvertently exacerbate the issue, leading to more severe pricing distortions and complexities. Therefore, it is crucial to establish an equilibrium between regulatory oversight and market autonomy, nurturing a resilient and efficient bond market that can propel sustainable and stable economic growth, especially in emerging economies.

References

Ang, Andrew, Jun Bai, and Hai Zhou. 2023. “The Great Wall of Debt: Real Estate, Political Risk, and Chinese Local Government Financing Cost.” Journal of Financial Data Science 9: 100098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfds.2023.100098.

Beber, Alessandro, and Marco Pagano. 2013. “Short-Selling Bans around the World: Evidence from the 2007–09 Crisis.” Journal of Finance 68 (1): 343–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01802.x.

Bris, Arturo, William N. Goetzmann, and Ning Zhu. 2007. “Efficiency and the Bear: Short Sales and Markets around the World.” Journal of Finance 62 (3): 1029–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01230.x.

Chan, Soon Huat, Kenneth A. Kim, and S. Ghon Rhee. 2005. “Price Limit Performance: Evidence from Transactions Data and the Limit Order Book.” Journal of Empirical Finance 12 (2): 269–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2004.01.001.

Chang, Eric C., Joseph W. Cheng, and Yinghui Yu. 2007. “Short-Sales Constraints and Price Discovery: Evidence from the Hong Kong Market.” Journal of Finance 62 (5): 2097–2121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01270.x.

Chang, Eric C., Yan Luo, and Jinjuan Ren. 2014. “Short-Selling, Margin-Trading, and Price Efficiency: Evidence from the Chinese Market.” Journal of Banking and Finance 48: 411–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.10.002.

Chen, Hui, Zhuo Chen, Zhiguo He, Jinyu Liu, and Rengming Xie. 2023. “Pledgeability and Asset Prices: Evidence from the Chinese Corporate Bond Markets.” Journal of Finance 78 (5): 2563–2620. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13266.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu. 2020. “The Financing of Local Government in China: Stimulus Loan Wanes and Shadow Banking Waxes.” Journal of Financial Economics 137 (1): 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.07.009.

Chen, Jun, Bin Ke, Donghui Wu, and Zhifeng Yang. 2018. “The Consequences of Shifting the IPO Offer Pricing Power from Securities Regulators to Market Participants in Weak Institutional Environments: Evidence from China.” Journal of Corporate Finance 50: 349–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.10.007.

Ding, Yi, Wei Xiong, and Jinfan Zhang. 2022. “Issuance Overpricing of China’s Corporate Debt Securities.” Journal of Financial Economics 144 (1): 328–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.06.010.

Geng, Zhe, and Jun Pan. 2024. “The SOE Premium and Government Support in China’s Credit Market.” Journal of Finance 79 (5): 3041–3103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13380

Harrison, J. Michael, and David M. Kreps. 1978. “Speculative Investor Behavior in a Stock Market with Heterogeneous Expectations.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 92 (2): 323–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884166.

Jin, Shuang, Wei Wang, and Zilong Zhang. 2023. “The Real Effects of Implicit Government Guarantee: Evidence from Chinese State-Owned Enterprise Defaults.” Management Science 69 (6): 3650–74. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4483.

Kim, Kenneth A., and S. Ghon Rhee. 1997. “Price Limit Performance: Evidence from the Tokyo Stock Exchange.” Journal of Finance 52 (2): 885–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04827.x.

Liu, Laura Xiaolei, Yuanzhen Lyu, and Fan Yu. 2017. “Local Government Implicit Debt and the Pricing of Chinese LGFV Debt.” Journal of Financial Research 12: 170–188. In Chinese. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2922946.

Miller, Edward M. 1977. “Risk, Uncertainty, and Divergence of Opinion.” Journal of Finance 32 (4): 1151–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1977.tb03317.x.

Qian, Yiming, Jay R. Ritter, and Xinjian Shao. 2024. “Initial Public Offerings Chinese Style.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 59 (1): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002210902200134X.

Ritter, Jay R. 2011. “Equilibrium in the Initial Public Offerings Market.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 3: 347–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-102710-144845.

Saffi, Pedro A. C., and Kari Sigurdsson. 2011. “Price Efficiency and Short Selling.” Review of Financial Studies 24 (3): 821–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhq124.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email