Let a Small Bank Fail: Implicit Non-guarantee and Financial Contagion

The long-standing government guarantee across China’s banking system, regardless of a bank’s systemic importance, ended on May 24, 2019, when regulators took over Baoshang Bank. Although large-scale liquidity injections and guarantees maintained market-wide liquidity, this policy shift sharply worsened interbank funding conditions, widening credit spreads and lowering funding ratios for small banks’ negotiable certificates of deposit relative to large ones. This triggered distress among other small banks due to diminished confidence in future bailouts, rather than heightened risk awareness, liquidity shortage, or balance sheet contagion. Our findings highlight the regulatory rationale for small-bank bailouts, as in the recent Silicon Valley Bank case. Furthermore, the reduced confidence in government guarantees within China’s banking system improves price efficiency, credit allocation, and discourages excessive risk-taking among small banks.

Bank bailouts are prevalent and thus are often well anticipated. The classical theory underlying the anticipation of bank bailouts (or implicit guarantee) is the concept of “too big to fail” (TBTF). According to this theory, the failure of a large bank, due to its substantial assets and interconnectedness with other institutions, has the potential to trigger a systemic financial crisis through balance sheet contagion (e.g., Allen and Gale 2000, Eisenberg and Noe 2001) or fire sales (e.g., Duarte and Eisenbach 2021; Greenwood, Landier, and Thesmar 2015). However, TBTF falls short in explaining rescuing small banks, a practice that is frequently observed. A recent example is US regulators’ decision to go beyond the standard deposit insurance limit of $250,000, extending coverage to all deposits of Silicon Valley Bank, a systemically unimportant (SU) bank that failed in March 2023.

What is the rationale behind bailing out small banks? What would be the consequences of not rescuing them? What are the impacts of implicit guarantees associated with small banks?

In a recent working paper (Liu, Wang and Zhou 2024), we address these questions by examining an unexpected bailout policy change following a small bank’s collapse in China. This unexpected policy shift was triggered by the regulatory takeover of Baoshang Bank, a distressed city-level commercial bank. Historically, since the failure of Hainan Development Bank in 1998, distressed banks were universally bailed out without undergoing bankruptcy proceedings, with all creditors receiving full repayments.1 However, following the takeover of Baoshang Bank, a significant change occurred on May 24, 2019, when it was announced that only creditors with claims below 50 million RMB would receive full coverage, while those with claims exceeding that amount should anticipate some losses. This announcement marked the first instance of regulatory authorities deviating from the full bailout scheme in the preceding two decades.

Interestingly, shortly after the bailout policy change, several other small banks fell into distress. For example, the Bank of Jinzhou, a Hong Kong–listed, city-level commercial bank, experienced severe liquidity distress following the event. In the interbank market, between May 25 and June 9, 15 days after the bailout policy shift, the bank issued only two negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs) successfully, raising 0.2 billion RMB in total. In comparison, prior to the bailout policy change, the bank successfully issued 18 NCDs in 15 days, raising 5.8 billion RMB in total. On June 10, 2019, the regulatory authorities issued temporary guarantees for the bank’s NCD issuance, which were later revoked on July 30, 2019.

In addition to the Bank of Jinzhou, several other small banks experienced severe funding difficulties following the bailout policy shift, including a joint-stock commercial bank (Hengfeng Bank), a rural commercial bank (Chengdu Rural Commercial Bank), and three city-level commercial banks (Bank of Jilin, Harbin Bank, and Bank of Gansu).2 All of these banks received government assistance, with no creditors suffering losses.3

In light of the observation that the regulatory authorities chose not to bail out all Baoshang creditors in full, the implied probability that future bailouts will be extended to SU banks declines significantly. As a result, this diminished confidence in future government bailouts (or implicit non-guarantee) will be priced on SU banks’ NCD issuance, resulting in an increased cost of borrowing. A simple theoretical model is developed to formalize this idea and generate hypotheses for subsequent empirical analysis. Notably, the theory assumes TBTF, where government guarantees are always extended to systemically important (SI) banks. Therefore, according to the theory, the bailout policy change would affect only those SU banks.

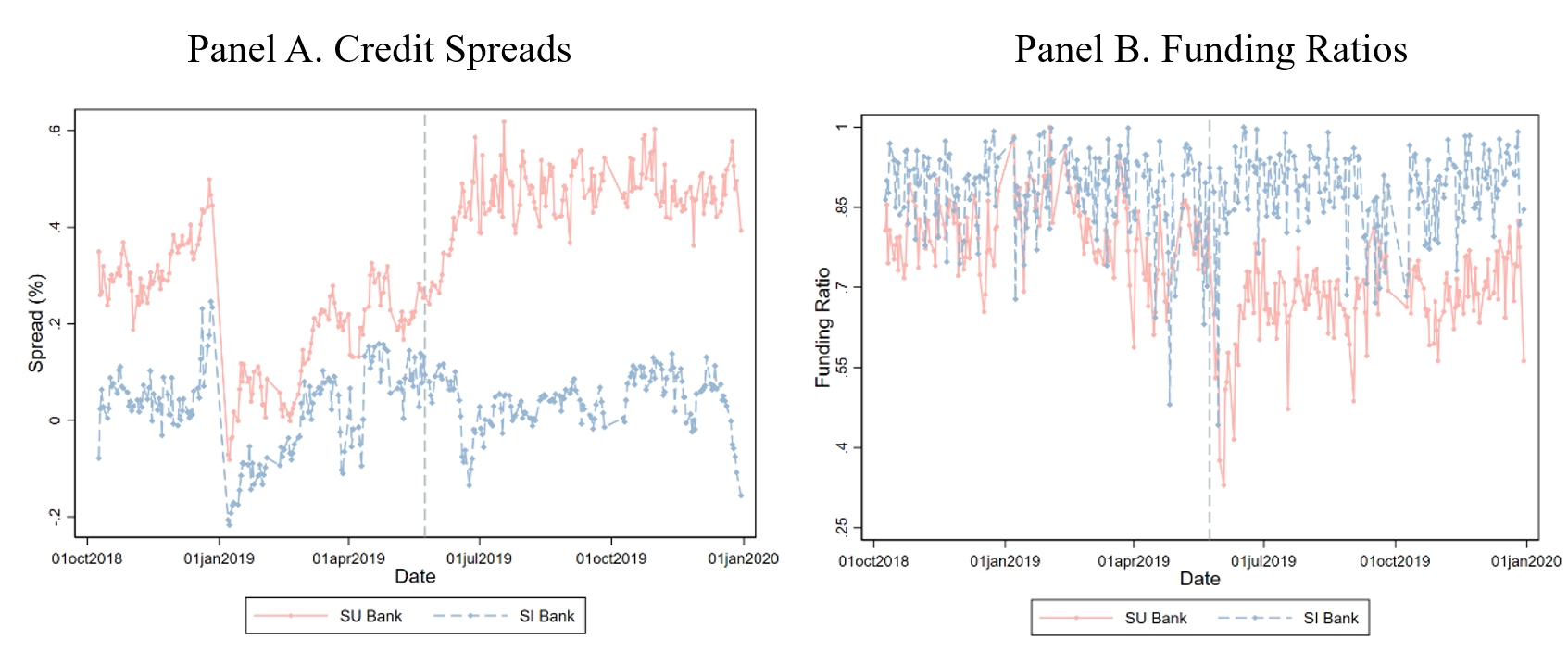

The main empirical finding reveals that departing from the full bailout policy for small banks resulted in a significant deterioration of funding conditions and subsequent failures of several other small banks. Figure 1 provides preliminary evidence that the bailout policy shift increased credit spreads and decreased funding ratios for SU banks, while having little influence on SI banks. Panel A of Figure 1 plots the simple average of daily credit spreads issued by SU and SI banks from October 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019, suggesting that the event pushed up the differences in NCD issuance interest rates between the SU and SI banks, and the differences are quite persistent. Panel B of Figure 1 plots the simple average of funding ratios issued by SU and SI banks during the same sample period, indicating that the funding ratio on NCD issuance declines significantly for SU banks following the bailout policy change but remains stable for SI banks. The data patterns observed in Figure 1 are further validated using the difference-in-differences methodology, where samples are divided into SU (treatment group) and SI (control group) banks.

Figure 1. Daily Average Credit Spreads and Funding Ratios

Notes: This figure presents the daily average credit spreads and funding ratios on NCD issuance from October 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019, and the event day is May 24, 2019. Spreadit is the difference between the issuance interest rate on the NCD and the Shibor interest rate with the same term to maturity on the same day, which is calculated using the successful sample. FdRatioit is the ratio of the funded size to the planned size on NCD issuance, which is calculated using the full sample. Treati is a dummy equal to one if bank i is systemically unimportant as certified by the People’s Bank of China and zero otherwise. Panel A plots the simple average of Spreadit. Panel B plots the simple average of FdRatioit.

To further establish that the spillover is caused by the implicit non-guarantee extended to SU banks, supplementary empirical analyses are conducted to rule out other alternative channels, such as risk awareness, market-wide liquidity shortage, fundamental contagion, and endogenous interbank exposures. For example, if the observed data patterns are mainly driven by the increased risk awareness for banks that are similar to the failed bank, then, for SU banks that are not comparable to Baoshang Bank, we would not expect to see significant widening of credit spreads or declines in funding ratios for them. To rule out this mechanism, we define privately controlled banks or city-level commercial banks that are comparable in size to Baoshang Bank as similar banks. The evidence shows that the observed patterns of credit spreads and funding ratios remain largely unchanged if we exclude similar banks from our treatment group.

Furthermore, we provide additional supporting evidence on the implicit non-guarantee channel: SU banks experience more pronounced impacts on NCD issuance in terms of heightened borrowing costs and decreased funding ratios when located in a province with weaker fiscal capacity.4

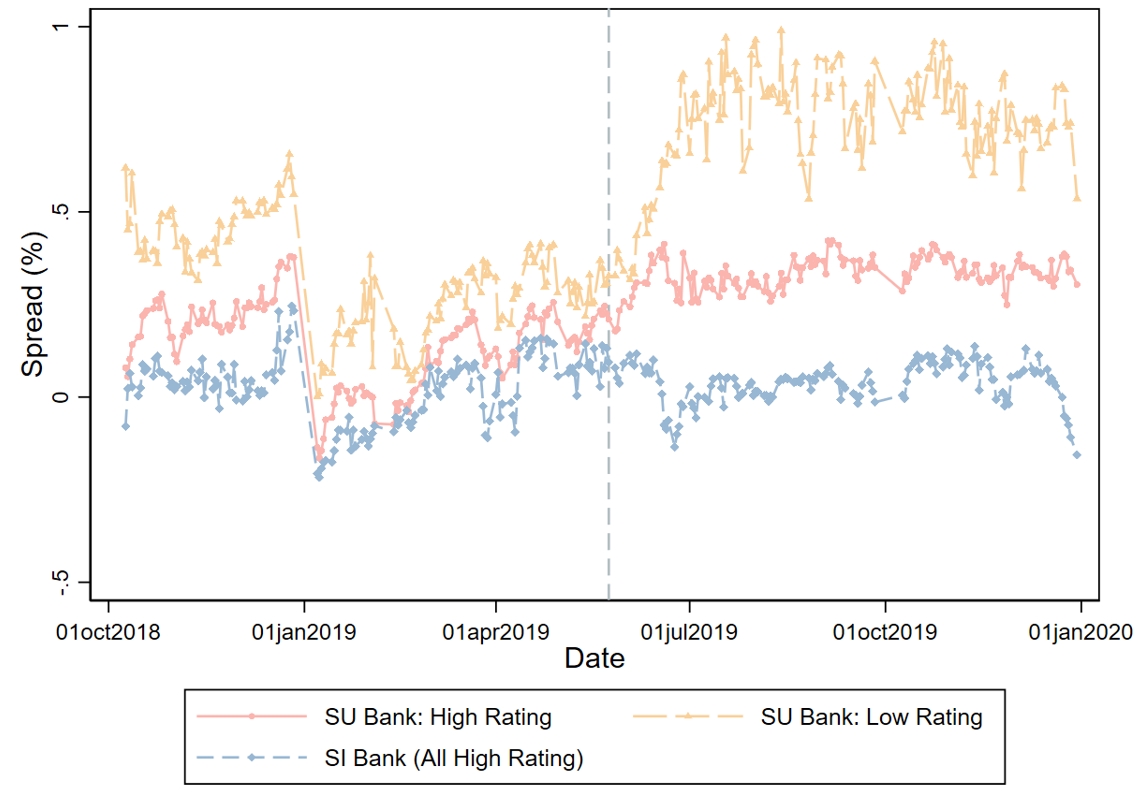

Another piece of evidence supporting the implicit non-guarantee channel, as predicted by the model, is the increased sensitivity of credit spreads in NCD issuance to SU banks’ credit risks, a pattern that should not be observed in SI banks. Figure 2 illustrates a substantial widening of the credit spread gap between high- and low-rated SU banks following the bailout policy shift. This model prediction is then formally tested using bank fundamentals (e.g., return on assets and nonperforming loans) as proxies for credit risks. Interestingly, the credit spreads exhibit insensitivity to bank fundamentals before the event for both SI and SU banks. However, post-event, a noteworthy shift occurs, but only for SU banks, where they become statistically significant.

Figure 2.Daily Average Credit Spreads with Different Credit Ratings

Notes: This figure presents the daily average credit spreads on NCD issuance with different credit ratings from October 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019, and the event day is May 24, 2019. Spreadit is the difference between the issuance interest rate on the NCD and the Shibor interest rate with the same term to maturity on the same day. Treati is a dummy equal to one if bank i is systemically unimportant as certified by the People’s Bank of China and zero otherwise. HRatingit is a dummy equal to one if the credit rating is AA+ or AAA and zero otherwise.

Our study contributes to the understanding of the implicit guarantee and bank bailout in China’s banking sector. Implicit guarantees, provided by central or local governments or backed by financial institutions, constitute a fundamental element of China’s financial system.5 Our findings confirm the strong public belief in government bailouts that were expected to be extended to small banks in China before the bailout policy shift. Despite being acknowledged as a fundamental challenge for the Chinese banking sector (Song and Xiong 2018, Zhu 2016), little research has been conducted on the effect of systemic bailouts on banks’ behavior as well as the overall risk in the banking sector. The difficulty in addressing this question stems from the fact that in China, there is little variation in the government guarantee, and even if there were, changes in implicit guarantees are difficult to observe or quantify.6 However, our empirical approach enables us to rule out alternative mechanisms and identify a shift in market beliefs about future government guarantees. Our study fills this gap. We provide compelling evidence that systemic government guarantees distort pricing, lead to inefficient credit allocation in the interbank market, and encourage excessive risk-taking by small banks.

Finally, this study highlights a novel contagion mechanism driven by updating beliefs about future bailouts following the regulator’s decision to address a small bank’s collapse. Interestingly, conventional interventions such as liquidity injections may be ineffective at mitigating this spillover effect. It is reasonable to anticipate that, in the absence of these interventions, an implicit non-guarantee could interact with other spillover mechanisms, possibly inducing a more pronounced negative impact on financial stability. Therefore, the failure of an SU bank could potentially contribute to systemic risk. Interestingly, we find that the impact of government guarantees on small banks mirrors the trade-off seen in TBTF: it safeguards financial stability ex post while challenging the ex ante efficiency.

From this perspective, it may be rational for regulators to bail out a small distressed bank, as the associated costs are likely far lower than rescuing a larger institution or addressing contagion-driven failures of multiple banks. These findings help explain not only China’s long-standing systemic bailout scheme, but also US regulators’ recent decision to invoke the systemic risk exception (made with respect to compliance with the least-cost resolution requirement), insuring all depositors in Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Given that small community banks and credit unions were also rescued, the underlying reason behind government bailouts should go beyond avoiding systemic financial crises. Rather, the rationale could be linked to these banks’ previously assumed obligations to cooperate with central or local government policies, as well as to ex post social harmony and stability.

2 To be specific, among the six banks, the Bank of Jinzhou and Hengfeng Bank experienced direct intervention by the central government, while the other four banks were bailed out by the local government via share purchase or private placement, where all the bailouts happened in the aftermath of the bailout policy shift. For details, see the 2020 Annual Report to Congress, the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, December 2020, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Chapter_2_Section_2--Vulnerabilities_in_Chinas_Financial_System_and_Risks_for_the_United_States.pdf

3 However, we believe that these bailouts would not have an impact comparable to the bailout policy change following the takeover of Baoshang Bank, in terms of magnitude and persistence, because it marked the first deviation from the full bailout policy in the past 20 years.

4 It is worth noting that fiscal capacity may endogenously affect the probability of bank failure through other channels, such as the stringency of bank stress tests (see Faria-e Castro, Martinez, and Philippon 2017). However, this concern should be alleviated in our case, as in most instances the regulatory framework and supervisory policies are established by the central government, which arguably should not be influenced by the local government’s fiscal capacity.

5 See, for example, Jin, Wang, and Zhang (2023) and Geng and Pan (2024) for studies on guarantees extended to debts issued by state-owned enterprises; Liu, Lyu, and Yu (2021) for the impacts of government guarantees offered to public bonds issued by local government financial vehicles; Allen et al. (2023) for the implicit guarantee provided by financial intermediaries on trust products in China; Huang, Huang, and Shao (2023) for banks’ choices of extending guarantees to investors in wealth management products; and Cong et al. (2019) for the implicit guarantee on bank loans made to state-connected firms during recessions.

6 For example, Gormley, Johnson, and Rhee (2015) provide evidence that even with a promised no-bailout scheme, beliefs of TBTF were not eliminated because investors believed that this policy was not time consistent. In addition, many studies, e.g., Berndt, Duffie, and Zhu (2022), adopt a structural approach to estimate the implied probability of government guarantee from the market data.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

Allen, Franklin, and Douglas Gale. 2000. “Financial Contagion.” Journal of Political Economy 108 (1): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/262109.

Allen, Franklin, Xian Gu, C. Wei Li, Jun “QJ” Qian, and Yiming Qian. 2023. “Implicit Guarantees and the Rise of Shadow Banking: The Case of Trust Products.” Journal of Financial Economics 149 (2): 115–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2023.04.012.

Berndt, Antje, Darrell Duffie, and Yichao Zhu. 2022. “The Decline of Too Big to Fail.” Social Science Research Network Working Paper No. 3497897. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3497897.

Cong, Lin William, Haoyu Gao, Jacopo Ponticelli, and Xiaoguang Yang. 2019. “Credit Allocation Under Economic Stimulus: Evidence from China.” Review of Financial Studies, 32(9): 3412–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz008.

Duarte, Fernando, and Thomas M. Eisenbach. 2021. “Fire-Sale Spillovers and Systemic Risk.” Journal of Finance 76(3): 1251–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13010.

Eisenberg, Larry, and Thomas H. Noe. 2001. “Systemic Risk in Financial Systems.” Management Science 47 (2): 236–49. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.47.2.236.9835.

Faria-e-Castro, Miguel, Joseba Martinez, and Thomas Philippon. 2017. “Runs versus Lemons: Information Disclosure and Fiscal Capacity.” Review of Economic Studies 84 (4): 1683–1707. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdw060.

Geng, Zhe, and Jun Pan. 2024. “The SOE Premium and Government Support in China’s Credit Market.” Journal of Finance 79 (5): 3041–3103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13380.

Gormley, Todd A., Simon Johnson, and Changyong Rhee. 2015. “Ending ‘Too Big to Fail’: Government Promises versus Investor Perceptions.” Review of Finance 19 (2): 491–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfu015.

Greenwood, Robin, Augustin Landier, and David Thesmar. 2015. “Vulnerable Banks.” Journal of Financial Economics 115 (3): 471–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.11.006.

Huang, Ji, Zongbo Huang, and Xiang Shao. 2023. “The Risk of Implicit Guarantees: Evidence from Shadow Banks in China.” Review of Finance 27 (4): 1521–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfac061.

Jin, Shuang, Wei Wang, and Zilong Zhang. 2023. “The Real Effects of Implicit Government Guarantee: Evidence from Chinese State-Owned Enterprise Defaults.” Management Science 69 (6): 3650–74. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4483.

Liu, Laura Xiaolei, Yuanzhen Lyu, and Fan Yu. 2021. “Local Government Implicit Debt and the Pricing of LGFV Bonds.” Journal of Financial Research, 12: 170–188, in Chinese.

Liu, Liyuan, Xianshuang Wang, and Zhen Zhou. 2024. “Let a Small Bank Fail: Implicit Non-guarantee and Financial Contagion.” Social Science Research Network Working Paper No. 4581919. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4581919.

Song, Zheng, and Wei Xiong. 2018. “Risks in China’s Financial System.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 10: 261–86. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-110716-032402.

Zhu, Ning. 2016. China’s Guaranteed Bubble. McGraw-Hill Education.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email