How House Prices Affected China’s Birth Rate Decline

China’s birth rate decline since 2016 coincided with a steep rise in urban house prices, sparking questions about a potential causal link. We explore this link through a unique quasi-experiment, revealing a previously underexplored channel through which house prices influence births, and discuss the implications of their research for China’s housing market and demographic future.

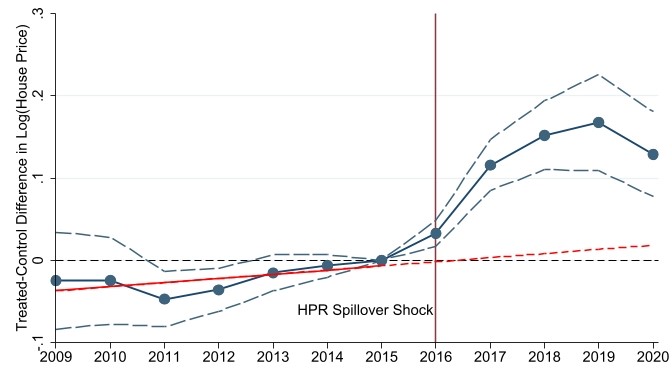

China has experienced a significant decline in birth rates since 2016. Before this recent decline, the birth rate had averaged approximately thirteen per thousand since the early 2000s, remaining below the replacement level. Concerns over an aging population led to the relaxation of the one-child policy in 2013, but it failed to significantly boost birth rates. In fact, the birth rate fell rapidly from thirteen per thousand in 2016 to six per thousand recently. This precipitous decline, seen in both the raw birth rate and the birth rate for women of childbearing age (Figure 1), caused the country’s population to peak in 2023. For China, the potential consequences include labor shortages, increased pressure on elderly care systems, and slower economic growth (Prasad 2023). Globally, China’s birth rate decline could have far-reaching repercussions, reshaping global demographics, and shifting the balance of economic and political power.

Figure 1 The Coincidental Timing of the House Price Surge and Birth Rate Decline. Source: Annual data on the national birth rate from the China Statistical Yearbook; annual data on births per women of childbearing age from the authors’ calculation based on data from the China Statistical Yearbook and Population Census; monthly data on the national urban house price index from CityRE.

Interestingly, China’s birth rate decline coincided with a rapid rise in urban house prices. As shown in Figure 1, the national average urban house price index increased by 54% between 2016 and 2021, while the raw birth rate dropped by 45%, and the birth rate for women of childbearing age fell by 39% during the same period. This coincidence raises an important question: is there a causal link between the surge in urban house prices and China’s birth rate decline?

Studying this potential link is essential and challenging, as demographic shifts can influence house prices, which themselves reflect future expectations. Identifying valid instruments for house prices is difficult. For example, one commonly used strategy adopts instruments related to supply elasticity, but the interpretation of these instruments is complicated by the fact that cities with inelastic housing supply are often “superstar” cities that experience faster economic growth during boom episodes when house prices also rise. This can influence individuals’ opportunity costs through economic fundamentals, thereby affecting birth rates beyond the direct effect of house prices.

Quasi-experiment on how house prices affect birth rate decline

In a recent study (Liu and Zhang 2024), we investigate the causal effect of house prices on China’s birth rate decline. We use a unique quasi-experiment related to increased house prices in some Chinese cities to identify this effect. The background of this quasi-experiment is the prevalence of investment purchases in China’s housing market (Fang, Gu, Xiong, and Zhou 2015; Wu, Gyourko, and Deng 2016; Chen and Wen 2017; Glaeser et al. 2017) and the unintended consequences of policies aimed at controlling them. In 2016, major Chinese metropolises imposed house purchase restrictions to cool overheated housing markets by curbing local investment and speculation. We show in earlier work (Deng et al. 2022) that the unfulfilled investment demand from the regulated metropolises was redirected to nearby unregulated cities, our treated cities. This shock caused house prices to rise with no fundamental changes in these cities, compared to unregulated cities that are farther away, our control cities.

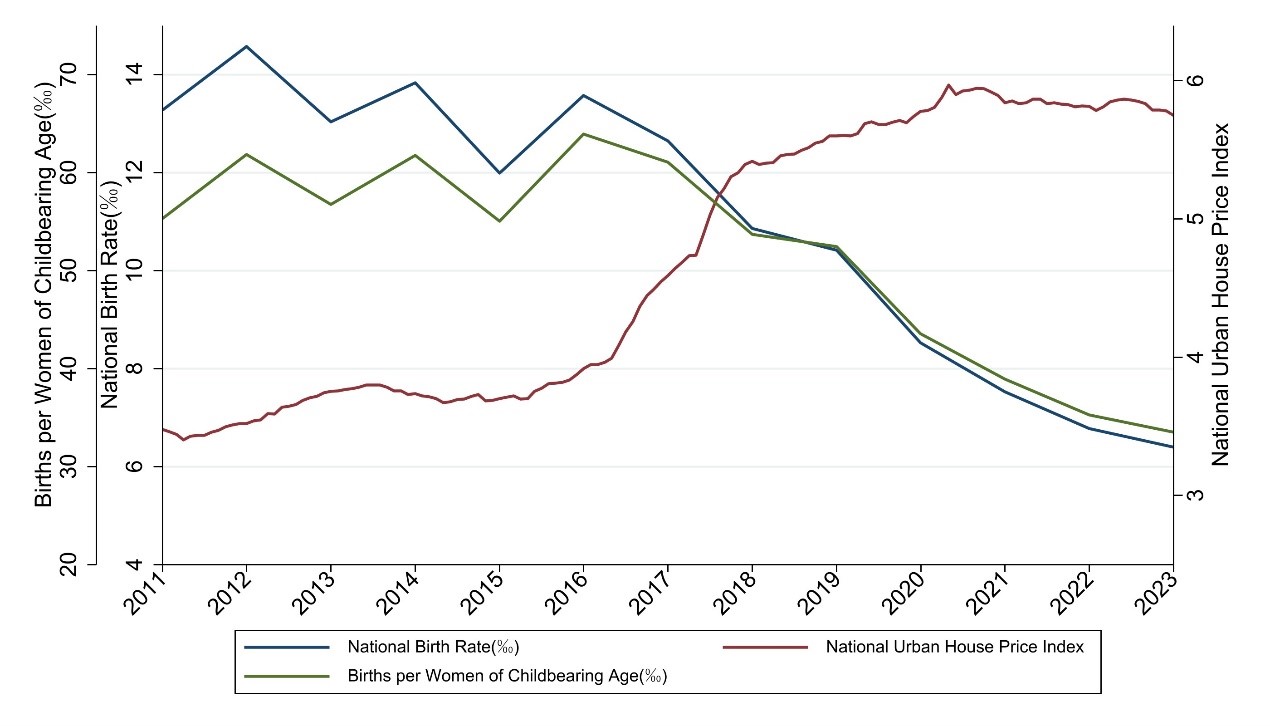

We use city-level urban house price indices from CityRE, and we manually collected city-level birth rates from annual statistical communiqués released by city governments. Using this urban house price quasi-experiment, we find results consistent with the interpretation that the speculation-driven rise in house prices significantly affected the decline of China’s birth rate. In our treated cities—the nearby unregulated cities—house prices sharply took off from trend (Figure 2), compared to the control cities, and the birth rate sharply fell off from trend (Figure 3).

Figure 2 House prices in the treated cities (nearby unregulated cities) diverged from the trend, increasing sharply and persistently compared to control cities, shortly after the quasi-experiment of the house purchase restriction spillover shock. Source: Authors’ calculation based on city-level urban house price index from CityRE.

Figure 3 The birth rate in the treated cities (nearby unregulated cities) diverged from the trend, declining sharply and persistently compared to control cities, one year after the quasi-experiment that abnormally increased urban house prices. Source: Authors’ calculation based on city-level birth rates from statistical communiqués.

We found that the sharp decline in birth rates in treated cities compared to control cities after the urban house price shock could not be attributed to any other factor we considered. One potential concern is that the treated and control cities may not be fully comparable. By design, treated cities were closer to regulated cities and may have been economically more vibrant. Indeed, our analysis revealed that treated cities were larger, experienced faster economic growth, had higher house price levels and similar wages, but lower fiscal expenditure per capita. To address these inherent differences, we controlled for these time-varying characteristics, in addition to city fixed effects and city-specific trends. Furthermore, we matched treated cities with control cities that were comparable in these characteristics and obtained similar results.

Another concern is that the negative but shrinking pre-trends in birth rates in treated cities compared to control cities could have affected our treatment effect estimates. One possible channel is that treated cities may have experienced a relatively growing population of women of childbearing age. To address this, we alternatively used the birth rate among women of childbearing age as the dependent variable and found quantitatively similar results, suggesting that the influence of this channel is limited.

We also considered the possibility that individual-level factors, such as education and income, could have affected birth trends before the house price shock. To address this, we utilized data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a nationally representative survey, and reconstructed annual birth records from its biennial survey waves. We estimated the treatment effect on the number of newborns at the individual level, controlling for these individual-level factors as well as individual fixed effects. Our analysis revealed a significantly negative treatment effect on individual-level births without observing significant pre-trends, further supporting our findings.

The economic magnitude of our estimated house prices’ effect on the birth rate decline is substantial. We estimate a semielasticity of 8.8, that a 10% abnormal increase in house prices reduced the birth rate by 0.88 per thousand people. Using spatial decay of the spillover shock and a potential outcome framework, we estimate that this house price shock alone reduced births by 2.46 million, relative to preexisting projections in the unregulated cities.

Rural aspiration for urban homeownership drove the house price impact on the birth rate decline

Why did the house price rise affect the birth rate? We explore this by using the individual-level CFPS data, and analyze treatment effects on the number of newborns to urban and rural individuals with different housing tenure statuses.

Figure 4 The number of newborns to women of childbearing age significantly declined in treated cities relative to control cities after the house price shock, specifically among rural dwellers who own homes but do not own urban homes. Source: Authors’ calculation based on individual-level annual birth records reconstructed from the CFPS.

We found a significant negative treatment effect on birth rates only among rural individuals who own their rural dwellings but do not own urban homes, which is also the majority group in our sample. Notably, these individuals have land for shelter allocated by their villages, so their shelter costs were not directly affected by the urban house price shock. Additionally, we observed no change in urban rents. Instead, the negative treatment effect on their birth rate is consistent with the interpretation that rural people's aspirations for urban homeownership drove the effect of house prices on the decline in birth rates during this episode, a hypothesis that we elaborate on below.

We did not find a significant negative treatment effect among urban homeowners, which is likely due to the offsetting effects of two conventional factors: the substitution effect of needing future shelter for new births, and the positive wealth effect. By design, urban homeowners were unaffected by the hypothesis that rural people’s aspirations for urban homeownership drive the effect of house prices on birth rates, and our results confirm that they do not explain the impact of house prices on the birth rate decline.

In contrast, we found imprecise but consistent effects among two other groups. Mobile individuals who own neither rural nor urban homes locally exhibited an imprecise negative effect, while rural individuals who own both rural and urban homes showed imprecise but positive effects. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis.

Our hypothesis of rural people’s aspirations for urban homeownership explaining house prices’ impact on the birth rate decline is related to the view that owning an urban home enhances marriage prospects and access to higher-quality education. We test both mechanisms and find supportive results.

Social norms in the marriage market exacerbated the effect of the house price shock on the birth rate decline

We observe that the birth rate decline of rural individuals without urban homeownership was especially noticeable in areas with a severe local sex imbalance, as proxied by a high local sex ratio among marriage-age individuals. Additionally, our analysis revealed that rural individuals in treated cities who do not own urban homes experienced a significant delay in marriage following the house price shock.

In China’s marriage market, urban homeownership (unlike rural housing, which is non-tradable) is a key factor for competition (Wei and Zhang 2011; Wei, Zhang, and Liu 2017). A joint survey by Wuhan University, CASS, Sina, and XinhuaNet found that 83% of rural respondents believe that young people from their hometown need to purchase a city home in order to get married. However, our individual-level dataset reveals that only 17% of rural individuals actually own an urban home. These statistics support the interpretation that the house price shock increased barriers to marriage, as dictated by marriage market norms that emphasize urban homeownership, thereby contributing to the decline in birth rates.

Figure 5 Red arrow: “House prices.” Speech bubble: “If you don't buy a home, you won’t get married!” Source: XinhuaNet.

Urban homeownership as a gateway to overcoming the urban-rural gap in educational resources also played a key role in house prices’ impact on the birth rate decline

The impact of rising urban house prices on birth rates among rural individuals was also particularly pronounced in areas with limited access to rural schools, as indicated by longer home-to-school travel times. In China, owning an urban home is closely tied to access to educational opportunities, as public-school enrollment is often linked to property ownership within a school’s catchment area and/or possession of an urban hukou, which is frequently obtained through urban homeownership. The existing literature has documented a significant urban-rural gap in educational attainment (e.g., Li et al. 2015). Furthermore, the recent consolidation and closure of rural schools (Ding, Wang, and Ye 2016) have increased travel distances and reduced local access to education, placing rural students who lack access to urban schools at an even greater disadvantage.

Our findings further indicate that rural married couples in the treated cities without urban homeownership reduced childbearing, a behavior consistent with the interpretation of a strategic adaptation. Facing higher barriers to accessing public education tied to urban homeownership, these couples appear to be reducing their fertility. Moreover, among these rural couples, we observe an increase in private educational investments conditional on having children, which is consistent with the view that rural families are compensating for the growing difficulty of accessing urban public education by turning to private alternatives, a resource they had previously relied on less.

Figure 6 In 2024, Nabu Village, Guangxi Province, an elementary school previously closed during the rural school consolidation initiative, reopened to serve the village’s students. Source: China Education News Net.

How our study contributes to the academic discussion on the birth rate

The literature has long suggested that house prices play a nonnegligible role in determining fertility outcomes (e.g., Becker 1960; Yi and Zhang 2010; Lovenheim and Mumford 2013; Dettling and Kearney 2014), with some studies suggesting that house price increases can increase fertility through a wealth effect (e.g., Lovenheim and Mumford 2013; Daysal et al. 2021; Ang et al. 2024). However, other studies have found that house price increases can also reduce fertility by raising the cost of sheltering (e.g., Yi and Zhang 2010; Clark 2012; Dettling and Kearney 2014; Liu, Liu, and Wang 2021; Meng, Peng, and Zhou 2023).

Our study provides the first causal evidence for a previously underexplored channel through which house prices impact fertility outcomes: by affecting the price of educational resources and marriage market benefits associated with homeownership. This channel, which has received less attention, may be equally important in understanding the relationship between house prices and birth rates. It is linked to classical theories on inequality, public versus private education, and human capital production (de la Croix and Doepke, 2003, 2004), as well as the competitive savings motive (Wei and Zhang 2011). Our results suggest that this channel cannot be ignored for understanding house prices’ effect on China’s recent birth rate decline.

Our findings highlight the importance of considering rural individuals and their interactions with urban housing markets when understanding and addressing China’s future demographics and human capital development. This consideration is related to the redistributive feature of housing markets (Chen, Fang, and Tang 2024). As Chetty et al. (2014) suggest, a child’s prospects for upward mobility are greatly influenced by relocating to the right areas and are negatively impacted by residential segregation. Furthermore, Heckman and Landersø (2022) show that family residential decisions are typically made early in children’s lives, often before their birth.

What does the future hold for China’s birth rate?

An open question remains as to what will happen to China’s birth rate as the housing market cools. Most of our treated cities are Tier 3 cities (Rogoff and Yang 2024), which experienced slow house price growth before 2016 but saw a sharp increase during 2016–2021. After our sample period, these cities began facing downward pressure on prices. Several factors contribute to the uncertainty surrounding this issue. First, local governments’ active management of land and housing prices, often through local government financing vehicles purchasing land at higher-than-market prices, may sustain housing costs despite cooling demand (Chang, Wang, and Xiong 2024).

Second, as expectations for rapid housing appreciation dwindle, user costs associated with homeownership may rise, further complicating individuals’ decisions regarding marriage and fertility. This could lead to delays in family formation during prime fertility years, potentially resulting in fewer children overall as individuals may postpone childbearing beyond their biological prime.

Third, the house price rise may have sparked a permanent change in societal expectations, where the traditional milestones of homeownership, marriage, and childbearing are no longer seen as essential life goals. As more individuals delay or forgo marriage and children due to housing affordability issues, these behaviors may become normalized. This shift in norms could mean that China’s birth rate remains low, even if urban house prices cool.

From a policy perspective, interventions beyond the housing market are needed. Addressing the urban-rural gap in public educational resources—for example, by decoupling urban school eligibility from homeownership and hukou—could alleviate some pressures that discourage childbearing. Policymakers may also need to reshape social norms around marriage and family formation, fostering an environment where young people feel empowered to start families without the burden of homeownership. Ultimately, it remains to be seen whether fertility norms will revert to pre-shock levels or whether the house price rise episode has permanently reshaped China’s demographic future.

Ziqian Liu, University of Washington

Yu Zhang, Peking University

References

Ang, Geer, Ya Tan, Yingjia Zhai, Fan Zhang, and Qinghua Zhang. 2024. “Housing Wealth, Fertility, and Children’s Health in China: A Regression Discontinuity Design.” Journal of Health Economics 97: 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2024.102915.

Becker, Gary S. 1960. “An Economic Analysis of Fertility.” In Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries, edited by Ansley J. Coale, 209–240. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chang, Jeffery Jinfan, Yuheng Wang, and Wei Xiong. 2023. “Price and Volume Divergence in China’s Real Estate Markets: the Role of Local Governments.” https://wxiong.mycpanel.princeton.edu/papers/Land.pdf.

Chen, Kaiji, and Yi Wen. 2017. “The Great Housing Boom of China.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9 (2): 73–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20140234.

Chen, Kaiji, Hanming Fang, and Yang Tang. 2024. “Housing Privatization as Intergenerational Redistribution.” [ADD LINK, IF AVAILABLE.]

Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez. 2014. “Where Is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (4): 1553–1623. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022.

Clark, William A. V. 2012. “Do Women Delay Family Formation in Expensive Housing Markets?” Demographic Research 27 (1): 1–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.1.

Daysal, N. Meltem, Michael Lovenheim, Nikolaj Siersbæk, and David N. Wasser. 2021. “Home Prices, Fertility, and Early-life Health Outcomes.” Journal of Public Economics 198: 104366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104366.

De la Croix, David, and Matthias Doepke. 2003. “Inequality and Growth: Why Differential Fertility Matters.” American Economic Review 93 (4): 1091–1113. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803769206214.

De la Croix, David, and Matthias Doepke. 2004. “Public versus Private Education when Differential Fertility Matters.” Journal of Development Economics 73 (2): 607–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2003.05.005.

Deng, Yinglu, Li Liao, Jiaheng Yu, and Yu Zhang. 2022. “Capital Spillover, House Prices, and Consumer Spending: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from House Purchase Restrictions.” Review of Financial Studies 35 (6): 3060–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhab091.

Dettling, Lisa J., and Melissa S. Kearney. 2014. “House Prices and Birth Rates: The Impact of the Real Estate Market on the Decision to Have a Baby.” Journal of Public Economics 110 (February): 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.09.009.

Ding, Yanqing, Shaoda Wang, and Xiaoyang Ye. 2016. “Why Have Some Local Governments Closed More Rural Schools than Others?” China Economics of Education Review (in Chinese) 1 (4): 3–34. [ADD LINK, IF AVAILABLE.]

Fang, Hanming, Quanlin Gu, Wei Xiong, and Li-An Zhou. 2016. “Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30 (1): 105–66. https://doi.org/10.1086/685953.

Glaeser, Edward, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, and Andrei Shleifer. 2017. “A Real Estate Boom with Chinese Characteristics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (1): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.93.

Heckman, James, and Rasmus Landersø. 2022. “Lessons for Americans from Denmark about Inequality and Social Mobility.” Labour Economics 77 (August): 101999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.101999.

Li, Hongbin, Prashant Loyalka, Scott Rozelle, Binzhen Wu, and Jieyu Xie. 2015. “Unequal Access to College in China: How Far Have Poor, Rural Students Been Left Behind?” China Quarterly 221: 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015000314.

Liu, Hong, Lili Liu, and Fei Wang. 2023. “Housing Wealth and Fertility: Evidence from China.” Journal of Population Economics 36 (1): 359–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00879-6.

Liu, Ziqian, and Yu Zhang. 2024. “The Effect of House Prices on Fertility: Evidence from House Purchase Restrictions.” https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4808554.

Lovenheim, Michael F., and Kevin J. Mumford. 2013. “Do Family Wealth Shocks Affect Fertility Choices? Evidence from the Housing Market.” Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (2): 464–75. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00266.

Meng, Lina, Lu Peng, and Yinggang Zhou. 2023. “Do Housing Booms Reduce Fertility Intentions? Evidence from the New Two-Child Policy in China.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 101 (July): 103920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2023.103920.

Prasad, Eswar S. 2023. “Has China’s Growth Gone from Miracle to Malady?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w31151. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31151.

Rogoff, Kenneth S., and Yuanchen Yang. 2024. “A Tale of Tier 3 Cities.” Journal of International Economics 152 (November): 103989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2024.103989.

Wei, Shang-Jin, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2011. “The Competitive Saving Motive: Evidence from Rising Sex Ratios and Savings Rates in China.” Journal of Political Economy 119 (3): 511–64. https://doi.org/10.1086/660887.

Wei, Shang-Jin, Xiaobo Zhang, and Yin Liu. 2017. “Home Ownership as Status Competition: Some Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Development Economics 127 (): 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.12.001.

Wu, Jing, Joseph Gyourko, and Yongheng Deng. 2016. “Evaluating the Risk of Chinese Housing Markets: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” China Economic Review 39 (July): 91–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.03.008.

Yi, Junjian, and Junsen Zhang. 2010. “The Effect of House Price on Fertility: Evidence from Hong Kong.” Economic Inquiry 48 (3): 635–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2009.00213.x.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email