The Effect of the China Connect

The “China Connect”, a carefully designed partial equity market liberalization in a capital-abundant country, provides a quasi-natural policy experiment to investigate the capital inflow effects of liberalization using firm-level data. Identification is further improved by the unique Chinese environment, including the trapped savings problem, significant domestic capital misallocation, and overall tight capital controls. In particular, we uncover a new learning channel of liberalization through improved market efficiency in addition to the traditional funding cost channel. Furthermore, liberalization makes domestic firms more sensitive to global shocks, which suggests a policy trade-off between efficiency and volatility for liberalization.

Few issues have stirred such passionate debate among researchers and policymakers as the effects of financial globalization. For developing countries, the topic is of enormous practical relevance, not least because countries such as China and India are still very much in the early stages of financial globalization and face numerous ongoing decisions about further integration. Although this is a long-studied topic, the existing literature has not provided robust evidence on the macroeconomic effects of liberalization (Henry 2007; Kose et al. 2009). Prior studies emphasized a funding cost channel of stock market liberalization for capital-scarce, small countries (Bekaert, Harvey, and Lundblad 2005; Chari and Henry 2004, 2008; Gourinchas and Jeanne 2006). Whether it applies to a large capital-abundant country like China is an open question, however (Liu, Spiegel, and Zhang 2021).

The Shanghai-Hong Kong “Stock Connect” program (the China Connect) provides a unique policy experiment to study the capital inflow effects of liberalization, including both short-run allocative efficiency and long-run heightened volatility. The China setting is interesting because liberalization allows only a subset of Chinese A-share firms to be traded by foreigners. Moreover, it did not coincide with other major economic reforms. Furthermore, the unique Chinese environment, such as large trapped savings, significant domestic capital misallocation, and overall tight capital controls, allows us to better identify new channels of foreign capital inflows.

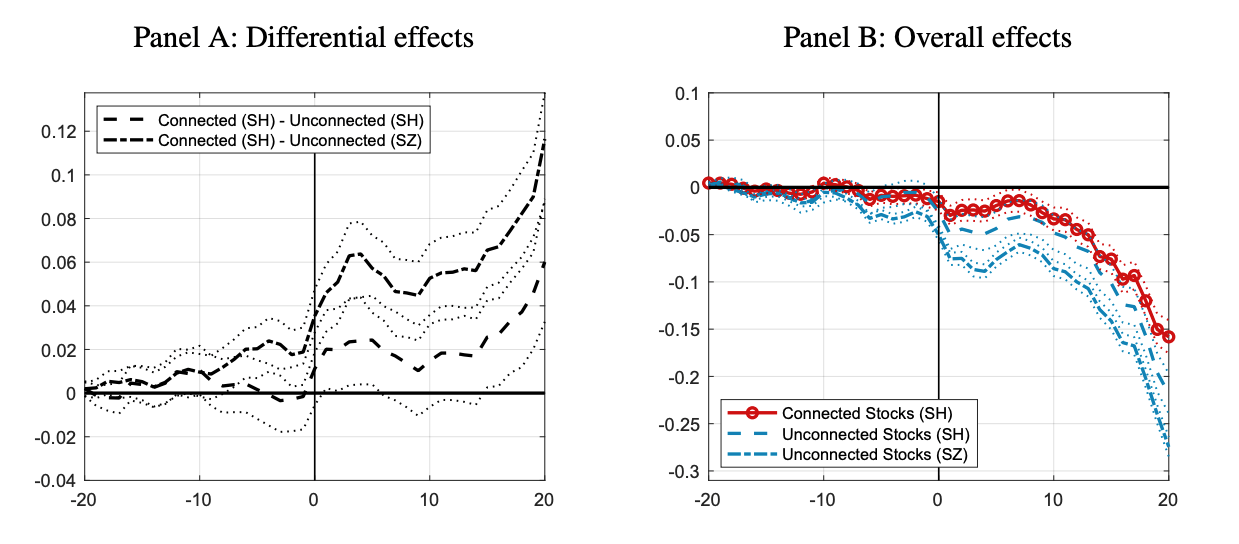

Liberalization in a capital-abundant country is quite different from that in a capital-scarce economy, as typically examined in the literature. Equity valuations in China have been, on average, elevated rather than depressed despite attendant risks. Thus, a general valuation decline is more likely upon liberalization. Furthermore, foreign presence in the mainland market might make it more efficient in an otherwise retail-driven setting. Taken together, asset prices might adjust downward after the Connect, especially for overvalued stocks (Figure 1, panel B). In addition, because liberalization brings in more foreign capital, connected stocks fall less (rise more) than unconnected ones (Figure 1, panel A).

Figure 1. Stock Return Responses Around the Connect Announcement

NOTE: Cumulative abnormal return based on a market model centered on November 10, 2014 (with 95% confidence interval).

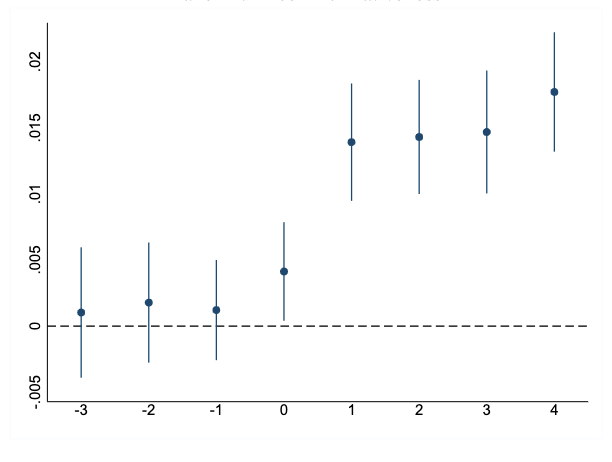

Liberalization also makes the stock market more efficient. Following Dávila and Parlatore (2021), we construct a firm-level measure of price informativeness, which utilizes R2 values from firm-level asset price regressions. The measure captures the information content of future earnings contained in stock prices. We find that this price informativeness measure of connected firms rises relative to unconnected ones after liberalization (Figure 2), which suggests that prices are more informative about future fundamentals post-liberalization. The improved price efficiency could come from more foreign-informed traders via liberalization (Lundblad et al. 2022), who produced new information and improved corporate governance (Kacperczyk, Sundaresan, and Wang 2021; Yoon 2021). It could also come from the regulatory change: the China Securities Regulatory Commission and the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong signed a memorandum of understanding on the China Connect in 2014 to share information and cooperate in law enforcement.

Figure 2. Improved Price Informativeness from Liberalization

NOTE. The figure plots the difference in price informativeness measures constructed following Dávila and Parlatore (2021) of connected and unconnected firms, i.e., the coefficient estimates with 95 % confidence interval from the estimation in the paper. Time 0 is the quarter for the China Connect.

Even though the China Connect is about stock market liberalization, there could also be real effects (Bond, Edmans, and Goldstein 2012). On the one hand, liberalization changes funding costs and thus corporate investment, i.e., the traditional funding cost channel emphasized in previous literature. In China’s case, capital investment is too large, at least in the aggregate. It is thus unclear whether this channel is important. On the other hand, liberalization can affect corporate investment decisions through a learning channel (Chen, Goldstein, and Jiang 2007). With higher price efficiency from liberalization, corporate investment becomes more efficient because managers learn more from stock prices. The learning channel is new to the literature and can be more easily identified in capital-abundant China.

We find supporting evidence for both channels. First, connected firms invest more than unconnected ones post-liberalization, especially those that are more financially constrained, such as small-sized and private-owned ones. Connected large and state-owned enterprises, however, do not increase their investment. Second, the investment-Q sensitivity is more correlated with the price informativeness measure for connected firms post-liberalization. This suggests that the information contained in the stock price is new and helpful to managers. Taken together, liberalization can bring in allocative efficiency by narrowing the existing domestic capital misallocation through relaxing financial constraints and by improving the market mechanism to signal value.

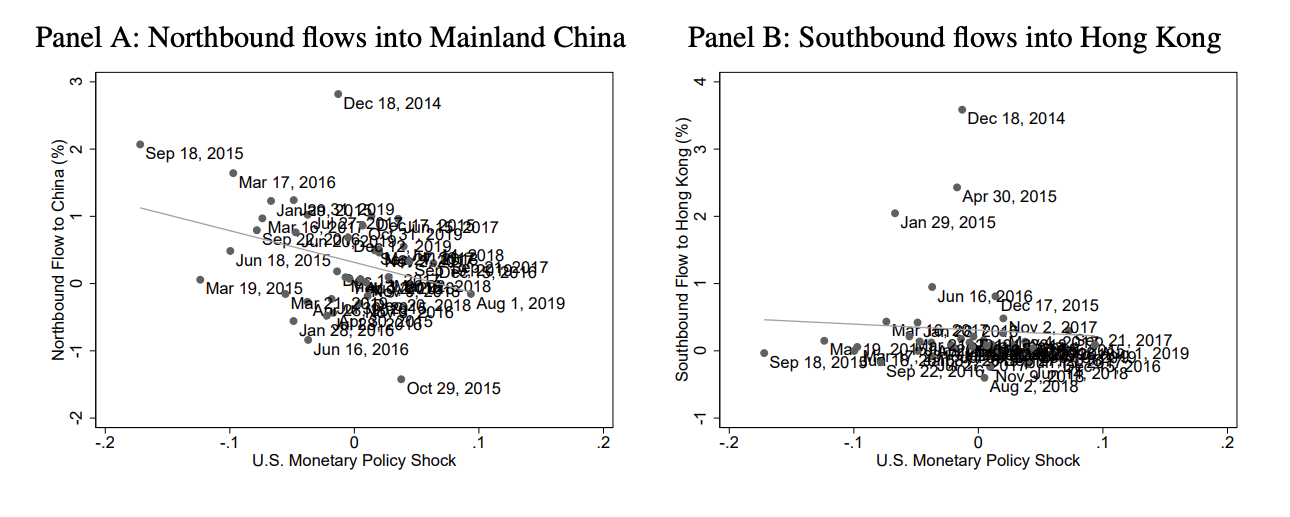

In addition to benefits, liberalization can bring in costs by exposing China to the influence of global shocks. Impressionistic evidence in Figure 3 indicates that capital flows into China through the Connect are negatively correlated with US monetary policy shocks on FOMC announcement days while capital flows into Hong Kong are not. We conduct a formal difference-in-differences estimation of both stock price and investment sensitivity to global shocks, including US monetary policy shocks (Rogers, Scotti, and Wright 2018), the VIX, the global financial cycle factor (Miranda-Agrippino and Rey 2020), and global risk aversion (Bekaert, Hoerova, and Xu 2021). Connected firms indeed experience higher sensitivity to those shocks than unconnected ones post-liberalization.

Figure 3. China Capital Flows and US Monetary Policy Shocks

NOTE. The figure shows the correlation between capital flows (through the Connect program) and US monetary policy shocks on FOMC announcement days (in Chinese local time).

Our empirical findings have strong policy implications. For countries like China and India, the allocative benefit of liberalization through market efficiency might be more important than the traditional funding cost. However, the transmission of global shocks is rather powerful, considering that China has imposed the tightest capital controls policy in the world. As a result, policymakers should fully understand the trade-off between allocative efficiency and volatility before implementing financial liberalization policies.

(Ma, International School of Finance, Fudan University; Rogers, International School of Finance, Fudan University; Zhou, Faculty of Business Administration, University of Macau)

References

Bekaert, Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, and Christian Lundblad. 2005. “Does Financial Liberalization Spur Growth?” Journal of Financial Economics 77 (1): 3–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.05.007.

Bekaert, Geert, Marie Hoerova, and Nancy R. Xu. 2021. “Risk, Monetary Policy, and Asset Prices in a Global World.” Social Science Research Network Working Paper No. 3599583. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3599583.

Bond, Philip, Alex Edmans, and Itay Goldstein. 2012. “The Real Effects of Financial Markets.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 4: 339–60. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-110311-101826.

Chari, Anusha, and Peter Blair Henry. 2004. “Risk Sharing and Asset Prices: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Journal of Finance 59 (3): 1295–1324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00663.x.

Chari, Anusha, and Peter Blair Henry. 2008. “Firm-Specific Information and the Efficiency of Investment.” Journal of Financial Economics 87 (3): 636–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.03.008.

Chen, Qi, Itay Goldstein, and Wei Jiang. 2007. “Price Informativeness and Investment Sensitivity to Stock Price.” Review of Financial Studies 20 (3): 619–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhl024.

Dávila, Eduardo, and Cecilia Parlatore. 2021. “Identifying Price Informativeness.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 25210. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25210.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Olivier Jeanne. 2006. “The Elusive Gains from International Financial Integration.” Review of Economic Studies 73 (3): 715–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2006.00393.x.

Henry, Peter Blair. 2007. “Capital Account Liberalization: Theory, Evidence, and Speculation.” Journal of Economic Literature 45 (4): 887–935. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.45.4.887.

Kacperczyk, Marcin, Savitar Sundaresan, and Tianyu Wang. 2021. “Do Foreign Institutional Investors Improve Price Efficiency?” Review of Financial Studies 34 (3): 1317–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa076.

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin Wei. 2006. “Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal.” International Monetary Fund Staff Papers, 56 (1): 8–62. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Financial-Globalization-A-Reappraisal-19435

Liu, Zheng, Mark M. Spiegel, and Jingyi Zhang. 2021. “Optimal Capital Account Liberalization in China.” Journal of Monetary Economics 117: 1041–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2020.08.003.

Lundblad, Christian T., Donghui Shi, Xiaoyan Zhang, and Zijian Zhang. 2022. “Are Foreign Investors Informed? Trading Experiences of Foreign Investors in China.” Asian Bureau of Finance and Economic Research Working Paper. https://abfer.org/media/abfer-events-2022/webinar-series/cmd/Are-Foreign-Investors-Informed_Trading-Experiences-of-Foreign-Investors-in-China_ChristianLunblad.pdf

Ma, Chang, John H. Rogers, and Sili Zhou. 2019. “The Effect of the China Connect.” Social Science Research Network Working Paper No. 3432134. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3432134.

Miranda-Agrippino, Silvia, and Hélène Rey. 2020. “US Monetary Policy and the Global Financial Cycle.” Review of Economic Studies 87 (6): 2754–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdaa019.

Rogers, John H., Chiara Scotti, and Jonathan H. Wright. 2018. “Unconventional Monetary Policy and International Risk Premia.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 50 (8): 1827–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12511.

Yoon, Aaron S. 2021. “The Role of Private Disclosures in Markets with Weak Institutions: Evidence from Market Liberalization in China.” Accounting Review 96 (4): 433–55. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2018-0606.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email