Empowering through Courts: Judicial Centralization and Municipal Financing in China

A more centralized judicial system can limit intervention by local governments and reduce court biases in favor of local governments. We find that following the judicial centralization reform which is gradually rolled out in China since 2014, local governments are more likely to lose lawsuits against their contractors, and creditors are indirectly disadvantaged as their residual claims become less valuable. This has significantly increased local governments’ financing costs and decreased their borrowing and spending.

A judiciary independent of political influences is essential to discipline government behaviors and has important economic consequences in many settings (North and Weingast, 1989). For high-level courts with substantial power in judicial interpretation, if political influences are powerful enough to compel these courts to override existing contract terms, isolating these influences and ensuring the judiciary independence can send a credible signal to the private sector about government adherence to contractual obligations, (Klerman and Mahoney, 2005). This is particularly important when addressing matters of public indebtedness, as governments may strategically default on debt obligations if they can affect court decisions to reduce the cost of default or even nullify debt outstanding (Dove, 2017, 2018).

In contrast, courts at the grassroots level have very limited power in judicial interpretation and are unlikely to override existing contract terms. Political influences over these courts can only affect to what extent the courts favor governments in determining the transfer between governments and their counterparties in situations not specified in the contract. In this sense, the judiciary’s role is best described as setting the transfer in an incomplete contract rather than affecting government adherence to contractual obligations.

In this paper (Hu, Peng, and Su, 2024), we study the impact of a high-profile judicial centralization reform aimed to alleviate local court capture on local governments’ debt capacity in China. With China’s high level of economic decentralization, local protectionism was ubiquitous in commercial lawsuits (Gong, 2004; Xu, 2011). At the core of this reform is to move the financial and personnel controls over local courts from the prefecture-level city governments to provincial-level governments. When initiating the reform plan in November 2013, the Chinese central government stated its goal was “promoting the unified management of personnel and budgets in local courts and procuratorates below the provincial level and exploring the establishment of a judicial jurisdiction system that is appropriately separated from administrative divisions.” This reform is widely recognized by judges, legal scholars, and economists to have significantly transformed China’s judicial system (Zhang and Ginsburg, 2019; Liu et al., 2022).

Judicial Centralization Reduces Local Court Bias

We start by examining whether the reform has changed court bias in favor of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), the legal entities that finance local public projects through financial tools such as municipal corporate bonds (MCBs) (Chen, He, and Liu, 2020). We construct the list of LGFVs based on all the MCBs, and then match it with all the court verdicts with these LGFVs as either plaintiffs or defendants. In total, 2,144 out of the 3,201 LGFVs are matched to at least one court verdict and the average number of verdicts involving these matched LGFVs is 33, much higher than that of non-LGFV firms.

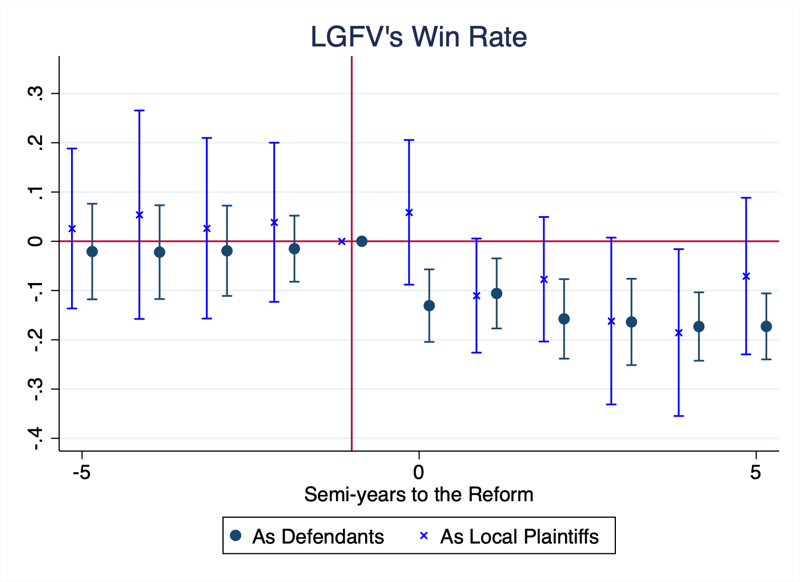

By exploiting the staggered roll-out of the reform across different cities, we find that following the reform in the LGFVs' cities, the win rate of LGFVs decreased by 17.2% when against non-local plaintiffs and by 11.6% when against local plaintiffs. Figure 1 shows the dynamic effect over time. In comparison, during our sample period, LGFVs' average win rate is 56.6% for lawsuits as plaintiffs and 50.1% as defendants. We also find that the magnitude of the effect was larger for non-local than local counterparties because non-local firms suffered from additional local protectionism bias before the reform (Liu et al., 2022). The decline in local LGFVs’ win rate is quantitatively larger when against contractors with a larger contract value. Regarding composition of the lawsuits, the reform also encourages smaller, less powerful counterparts to file lawsuits against LGFVs.

Figure 1: LGFVs’ win rate in court after the judicial reform

LGFVs’ Creditors Are Disadvantaged

The reform had little direct impact on the LGFVs’ creditors because in the data, more than 93.7% of the lawsuits involving LGFVs were against their business partners, such as contractors and suppliers. This is not surprising, because debt contracts are very simple and standard while procurement contracts can be much more complex and subject to disputes. The reform can affect the creditors indirectly because with LGFVs losing more in lawsuits, they have less money to pay creditors.

The empirical analysis confirms our prediction. We first find that the reform has increased the LGFVs’ default risk. Despite no formal default of MCBs, LGFVs have recently defaulted on non-standard debt obligations such as trust products. The average default rate is significantly higher in cities with the reform by about 2.0% as compared to the mean of 2.7%.

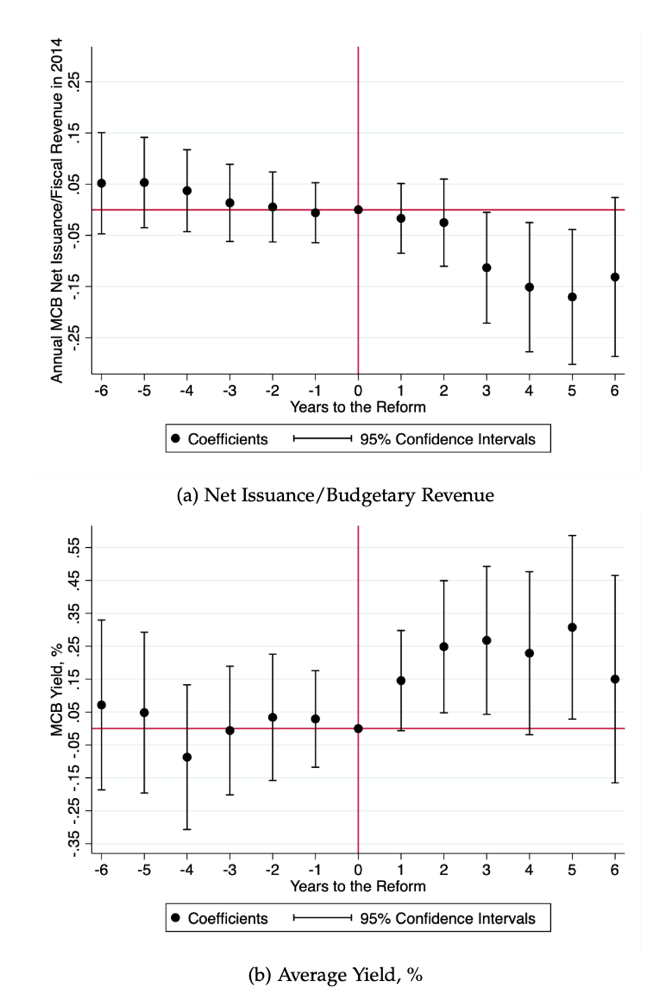

Consistent with the positive effect on LGFVs’ default, we find that the reform has undermined the LGFVs' debt capacity and spending. At the city level, the MCB net issuance as a fraction of the city government budgetary income decreased significantly after the judicial reform, with the magnitude of approximately 15% five years after the reform. The average MCB yield also increased gradually by around 0.25% since the second year of the reform. This is consistent with the hypothesis that a more favorable judicial environment for LGFVs’ contractors and suppliers indirectly disadvantages LGFVs’ bond creditors.

Figure 2: MCB Issuance and Yield after the Judicial Reform

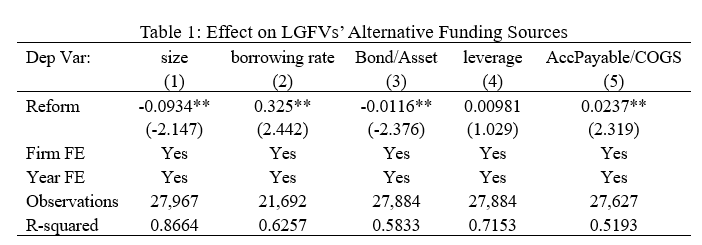

We then examine how LGFVs’ overall balance sheet is affected by the reform. As shown in Table 1, we find that after the reform, their total asset size decreased by 9.34% and average borrowing rates increased by 0.32%. The bond-to-asset ratio also decreased, suggesting a more pronounced response from bond investors. Unlike other financing sources, trade credit, as measured by account payable over cost-of-goods-sold, increased by 2.37%. The increase in trade credit is likely a joint outcome of LGFVs’ tighter financial constraints and a fairer legal environment that makes business partners more willing to extend trade credit.

This tightened debt capacity has real impacts, leading to significant drops in LGFVs’ spending by about 71.4%. Moreover, the city-level annual residential land supply, which typically requires initial investment from LGFVs, decreased by about 0.23 square meters per urban residenta, which is economically important compared to the mean of 1.47 square meters per urban resident. This means that the decreased borrowing capacity undermined the LGFVs’ main role in producing land inventories for local government to sell.

Contractors Offer More Favorable Prices

Reduced court protection may bring one benefit to LGFVs, if the contractors take into account the more favorable legal environment and offer lower contracting prices. Using value-added tax (VAT) invoice data and by comparing changes in prices paid by LGFVs relative to non-LGFVs for the same products from the same suppliers in the same year, we find that after the reform, the LGFVs’ relative price dropped significantly, by about 9.87%. Although it is difficult to compare this benefit effect to the effect on lawsuits, we think the result of increased default risk and tightened borrowing capacity implies that such ex-ante price adjustment is not large enough to fully offset the direct effect of the lawsuits.

There are many hypotheses for why the ex-ante price adjustment cannot fully offset the direct effect of lawsuits. For example, bond investors can be more risk averse while entrepreneurs have higher discount rates. As a result, contractors and suppliers will adjust ex-ante prices by less, and bond investors will disvalue the increased ex-post risk by more, leading to an overall increase in LGFVs’ cost. An alternative and non-exclusive hypothesis is that alleviating court capture may lead to more moral hazard problems from the contractors’ side, such as problems of project quality or delays, thereby increasing overall project costs. In the data, we do find that lawsuits involving contractors’ moral hazard increased significantly after the reform.

Final Thoughts

Whether tightened borrowing constraints hurt local government functioning or make budget constraints harder and prevent inefficient spending is another important question. Nonetheless, the judicial reform has also generated positive effects, such as more external investment as documented by Liu et al. (2022). Importantly, these positive effects should improve, the government borrowing capacity and hence cannot explain what we find in this paper.

References

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu. 2020. “The Financing of Local Government in China: Stimulus Loan Wanes and Shadow Banking Waxes.” Journal of Financial Economics 137 (1): 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.07.009.

Dove, John A. 2017. “Judicial Independence and US State Bond Ratings: An Empirical Investigation.” Public Budgeting and Finance 37 (3): 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbaf.12153.

Dove, John A. 2018. “It’s Easier to Contract than to Pay: Judicial Independence and US Municipal Default in the 19th Century.” Journal of Comparative Economics 46 (4): 1062–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2018.04.003.

Gong, Ting. 2004. “Dependent Judiciary and Unaccountable Judges: Judicial Corruption in Contemporary China.” China Review 4 (2): 33–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23461883.

Hu, Jiayin, Wenwei Peng, and Yang Su. 2024. “Empowering through Courts: Judicial Centralization and Municipal Financing in China.” Social Science Research Network Working Paper No. 4750742. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4750742.

Klerman, Daniel M., and Paul G. Mahoney. 2005. “The Value of Judicial Independence: Evidence from Eighteenth-Century England.” American Law and Economics Review 7 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahi005.

Liu, Ernest, Yi Lu, Wenwei Peng, and Shaoda Wang. 2022. “Judicial Independence, Local Protectionism, and Economic Integration: Evidence from China,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 30432. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30432.

North, Douglass C., and Barry R. Weingast. 1989. “Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England.” Journal of Economic History 49 (4): 803–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700009451.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011. “The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4): 1076–1151. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23071664.

Zhang, Taisu, and Tom Ginsburg. 2019. “China’s Turn toward Law.” Virginia Journal of International Law 59: 306. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.13051/17947.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email