The Externalities of ESG Disclosure

We study the real effects of mandatory environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure through the lens of regulatory salience. Our analysis exploits a unique setting in China, where firms differ in their exposure to a countrywide political campaign combating poverty based on whether they are required to disclose their contributions in their ESG reports (“treatment”). Using a difference-in-differences analysis, we find that treated firms significantly increase not only their donations to poverty alleviation, but also their pollution levels following the treatment. Negative environmental externalities increase with firms’ financial constraints and market competition. Further evidence shows that treated firms receive more government subsidies and state-owned bank loans, and achieve greater operating performance and valuation. These findings highlight mandatory disclosure as a form of mild government intervention on corporate behavior toward politically favored directions. However, this may lead firms to deprioritize other long-term investments.

The disclosure of ESG information has become increasingly prevalent worldwide. Today, almost all public companies regularly publish ESG reports alongside their annual reports. Most of these disclosures are made voluntarily, driven by investor and societal demand for more reliable ESG data (Ilhan et al. 2023), and following frameworks developed by international organizations, such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). Various jurisdictions have also implemented or plan to implement mandatory ESG disclosure requirements to better monitor corporate ESG actions, such as in the US (Securities and Exchange Commission 2024 mandate), EU (Non-Financial Reporting Directive in 2014, replaced by Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive in 2022), China (ISSB reporting by 2026), and Singapore (ISSB reporting by 2027). Despite its significance, the literature on mandatory ESG disclosure remains limited (Christensen, Hail, and Leuz 2021), and the few studies that exist mainly focus on its informational and incentive roles in disciplining corporate behavior (e.g., Jouvenot and Krueger 2020).

We propose an important yet largely unexplored channel, namely regulatory salience, through which mandatory ESG disclosure could affect corporate ESG actions. Specifically, we consider mandatory disclosure as a way for the government to “mildly” influence corporate actions toward politically desired outcomes. This contrasts with a strong form of state influence through its “visible hands,” such as laws, regulations, and direct government interference in corporate actions. It also differs from the subtler version of state influence using its “invisible hands” through government ownership and political connections in business. Disclosure mandates combine visible and invisible hands, as the government sets rules for reporting (but not actions) and corporations respond by changing their actions. Mandatory disclosure can also reflect the government’s political agenda, creating regulatory salience on certain issues, especially those related to ESG. Such a regulatory salience mechanism may yield different empirical predictions from the information and incentive channels of mandatory disclosure regarding corporate ESG actions.

We test the regulatory salience channel and provide insights into the real effects and potential externalities of mandatory ESG disclosures by leveraging a unique setting in China, where the regulator differentially requires listed firms to disclose their contributions to poverty alleviation. In 2016, the China Securities and Regulatory Commission (CSRC) started mandating all listed firms to disclose detailed quantitative information on their pecuniary and non-pecuniary contributions to the targeted poverty alleviation (TPA) program, a political campaign led by President Xi Jinping. Officially adopted in 2014, the TPA is central to China’s anti-poverty strategy and the CPC’s century goal of building a “moderately prosperous society.” It involves the establishment of a national poverty registration system, leading groups on poverty alleviation established at all administrative levels, clear guidelines, and targeted populations and timelines. The TPA disclosure mandate initiated two years later was an integral part of the campaign.

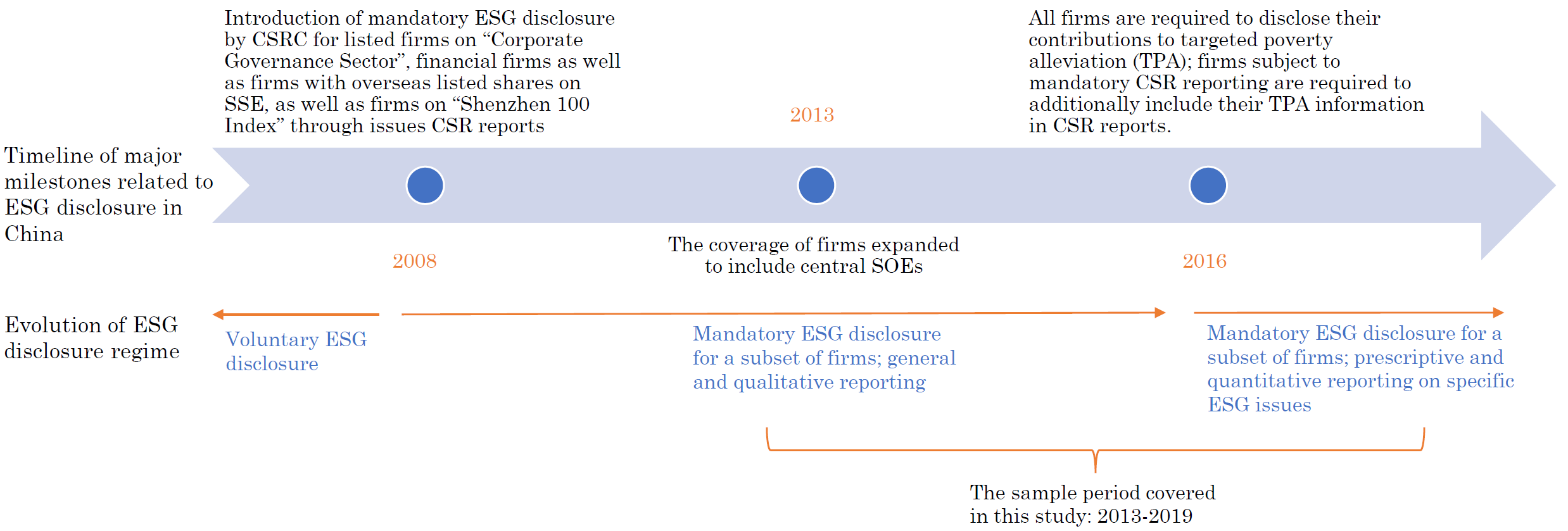

An important feature of this mandate is that regulators specifically require a predetermined subset of firms to disclose their TPA contributions in a more prominent way. In 2008, CSRC prescribed a subset of companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges to issue corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports, but with low standards and loose guidelines. In the 2016 TPA mandate, these firms are required to disclose their TPA information both in their annual reports and in their CSR reports, making them more exposed (sensitive) to this political campaign. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the ESG reporting landscape in China, highlighting the subgroup firms that are more exposed to the regulatory salience of TPA. This group of firms that have to issue CSR reports and disclose their TPA contributions in both the annual reports and the CSR reports constitute our treated group, as the salience of TPA is stronger for them given that such information is put under the spotlight rather than muddled with financial information. The treated group is defined by themes and sectors, and firms within this group may change over time, alleviating selection concerns. Our empirical evidence shows that potential selection issues do not bias our interpretations.

Figure 1. The Evolution of ESG Disclosures in China over Time

Using a sample of 2,376 firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges over the period 2013–2019 and applying a difference-in-differences methodology, we find that while all firms increased their TPA donations after the TPA disclosure mandate, treated firms that had to disclose such information more prominently in CSR reports, on average, increased their TPA donations by $500,000 more than control firms, representing a 7.5-times increase from the pre-mandate level. In addition to the direct effect of the TPA disclosure mandate, we examine its environmental externality. We find that treated firms, in response to the mandate, released an average of 5,258 more tons of toxic pollutants relative to control firms, translating into estimated costs of 5-15 million CNY (0.68-2.05 million USD) based on abatement investment estimations. These pollutants include a wide range of toxicants, including sulfur dioxide and heavy metals, even tiny amounts of which are found to be hazardous to public health.

We hypothesize that mandating disclosure on specific ESG issues reflects the government’s political agenda and creates regulatory salience on these issues, incentivizing reporting firms to focus more on the mandated issues. This is one way for the government to mildly influence corporate behaviors without directly intervening. However, this may lead firms to trade off more salient, shorter-term ESG goals with longer-term goals, especially when they face resource constraints. Due to the long timescale required to address environmental issues and the lack of immediate verifiable outcomes, firms may deprioritize environmental protection and allocate resources to TPA, which is more salient and has a clear timeline for achieving its goals. Therefore, mandatory ESG disclosure on TPA donations, while helping the government to influence corporations toward state-desired actions, may create negative externalities by distorting managerial incentives and resource allocation from a social welfare perspective. We interpret this as the “regulatory salience” effect of mandatory disclosure.

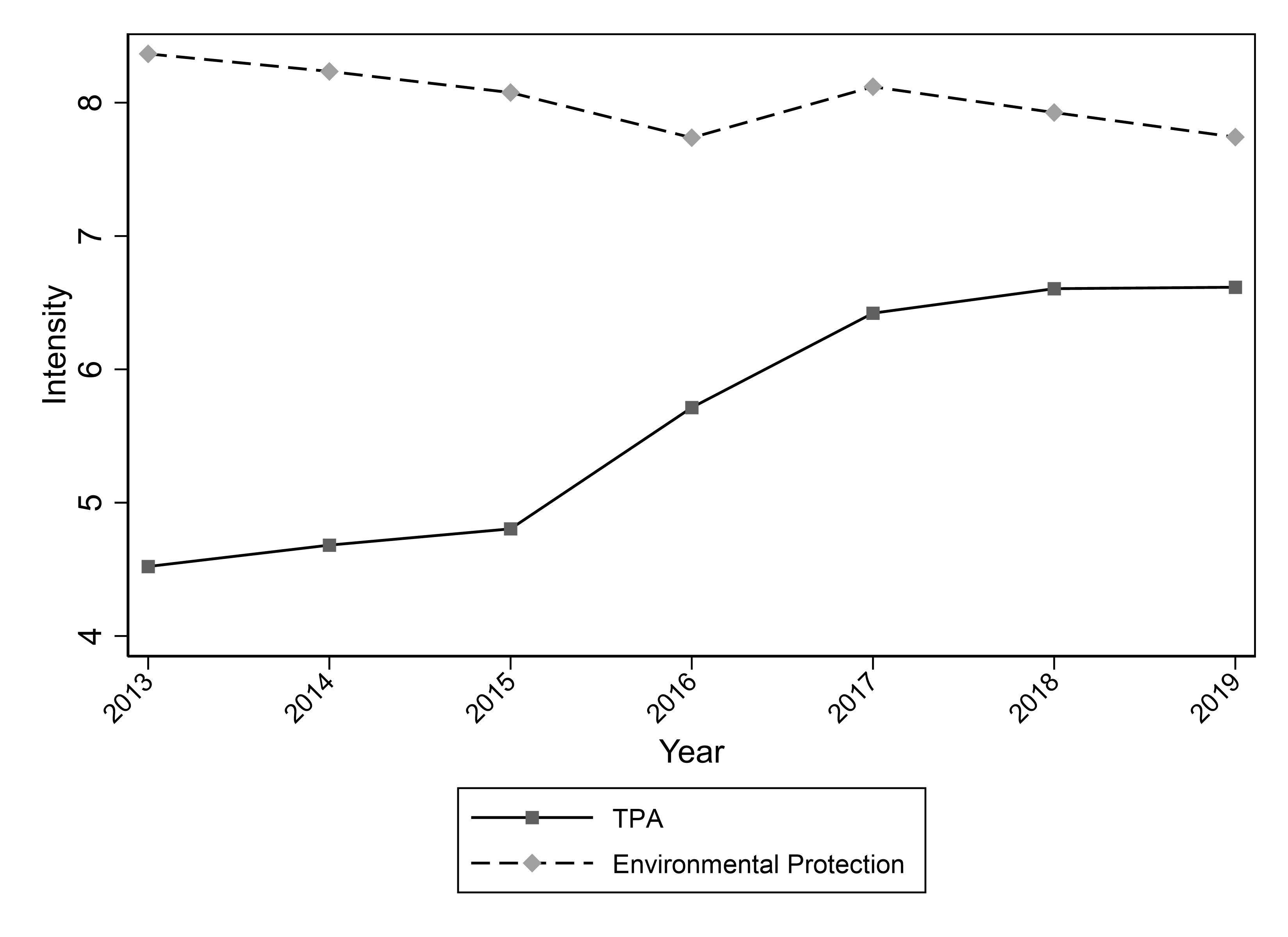

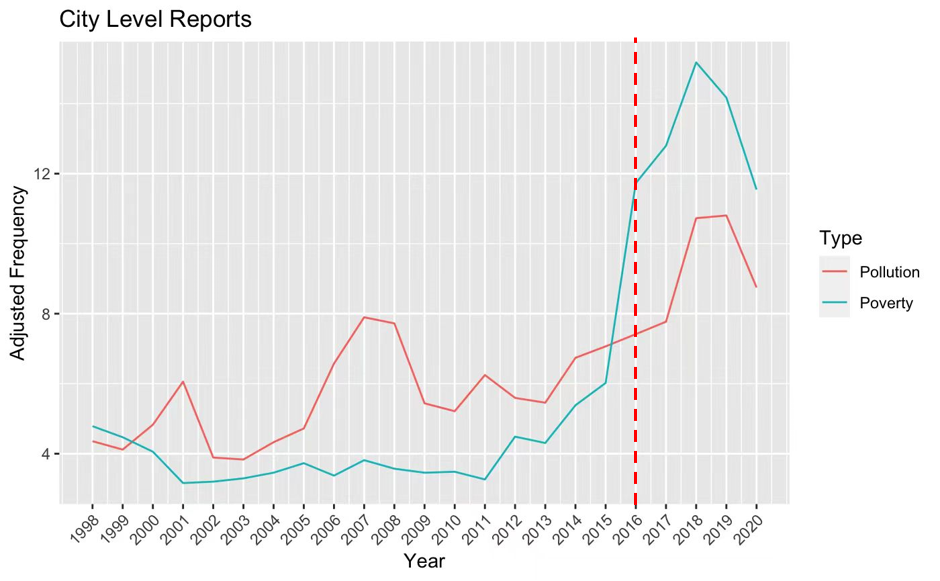

To substantiate this interpretation of the trade-off between the environmental (“E”) dimension and the more regulatorily salient social (“S”) dimension, we analyze keywords in news articles from People’s Daily and four major state-owned financial newspapers (Securities Daily, Securities Times, China Securities Journal, and Shanghai Securities Journal), as well as in local government officials’ reports. We observe a significant shift in regulators’ attention from environmental protection to poverty alleviation after the 2016 TPA disclosure mandate. This is reflected in both the media coverage intensity, measured by the number of news articles related to TPA and environmental protection, respectively (Figure 2A) and the frequency of these two keywords in city-level government working reports (Figure 2B).

Figure 2A. Firm-level overall media coverage on TPA vs. environmental protection

Figure 2B. Regulatory Salience of TPA vs. Environmental Protection in Local Government Working Reports

We also find that firms’ overall capital expenditure did not change, indicating that they reallocated resources internally from environmental spending to TPA donations. We further find that treated firms experienced lower costs of debt, received more government subsidies, and achieved greater operating performance and valuation. In other words, the TPA disclosure mandate has altered how the pie of ESG spending is divided, but not the overall size of the pie.

We perform several robustness tests to pin down the regulatory salience channel and rule out alternative explanations. First, we demonstrate that our findings are unlikely driven by a selection effect where politically important firms are pressured to issue ESG reports and increase TPA contributions. We find no significant difference in effects among state-owned enterprises, which typically champion political agendas. To further alleviate potential selection concerns, we employ a matching method, matching each treated firm with at most three control firms based on observable characteristics. Our results remain consistent after applying this matching. In addition, we show that the increased pollution levels are not mechanically driven by business expansion. Moreover, our findings are robust to alternative data on firm-level pollution and account for regulatory stringencies and penalties. Finally, in a dynamic analysis testing the pre-trend, we find no differences in donations and pollution levels between treated and control firms in the absence of the mandate.

We then conduct several cross-sectional analyses to further substantiate the regulatory salience mechanism. Firms facing greater financial constraints and fiercer competition are more incentivized to make such TPA-environment trade-offs to pander to local politicians’ preferences in exchange for favorable treatment. Consistent with this prediction, we find that the negative environmental externalities are concentrated in firms that are more financially constrained and in industries or regions with higher levels of product market competition.

Overall, our findings illuminate a mild form of government intervention on corporate actions toward politically favored directions through mandatory disclosures. However, the regulatory salience of the spotlighted issue may crowd out corporate spending on longer-term projects such as pollution abatement. This suggests that mandatory disclosure on specific ESG issues may create externalities on other stakeholders and society at large—either intended or unintended—a finding that has important policy implications for regulators mandating ESG disclosure worldwide.

References

Christensen, Hans B., Luzi Hail, and Christian Leuz. 2021. “Mandatory CSR and Sustainability Reporting: Economic Analysis and Literature Review.” Review of Accounting Studies 26 (3): 1176–1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09609-5.

Ilhan, Emirhan, Philipp Krueger, Zacharias Sautner, and Laura T. Starks. 2023. “Climate Risk Disclosure and Institutional Investors.” Review of Financial Studies 36 (7): 2617–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhad002.

Jiang, Yi, Ya Kang, and Hao Liang. 2024. “The Externalities of ESG Disclosure.” European Corporate Governance Institute–Finance Working Paper No. 880/2023. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4777001.

Jouvenot, Valentin, and Philipp Krueger. 2020. “Disclosure of Carbon Emissions in European Stock Markets.” Revue d'économie financière, 138 (2): 157–76.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email