Destination-Specific Export Expansions and Their Impact on Education and Long-Term Outcomes in China

We examine the short-run schooling consequences of destination-specific export expansions and their longer-run effects on adult outcomes. We find that export expansions to rich-country markets resulted in substantially higher high school enrollment rates. These expansions disproportionately favored urban children and those in regions with lower initial skill endowments. Subsequently, the effects translated into higher high school attainment, but not into higher rates of college education and above. More than a decade later, the affected cohorts exhibited significant differences in employment and fertility outcomes, highlighting the persistent effects of the shocks. The human capital effects were mainly driven by parental wage growth and the education premium in local labor markets.

Over the past four decades, many developing countries have significantly expanded their exports of manufactured goods. Evidence suggests that this surge in export manufacturing has significantly affected the educational distribution within these countries. Studies by Atkin (2016) and Li (2018) show that local expansions of low-skilled exports in Mexico and China led students to drop out of school during periods of rapid trade liberalization. Yet the long-term effects of destination-specific export expansions remain underexplored. The end of the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA), which eliminated textile and clothing (T&C) export quotas imposed by high-income countries, provides a perfect setting for examining this issue.

How MFA affected China’s T&C exports

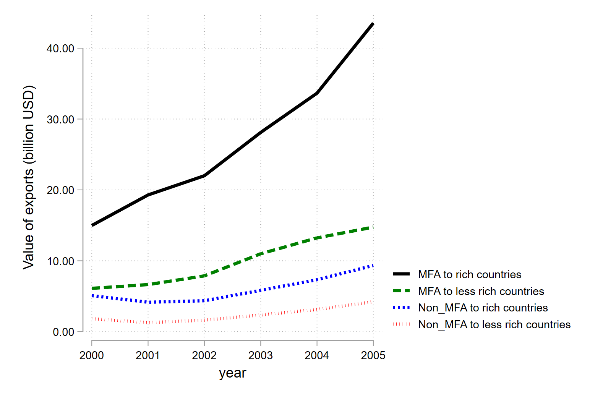

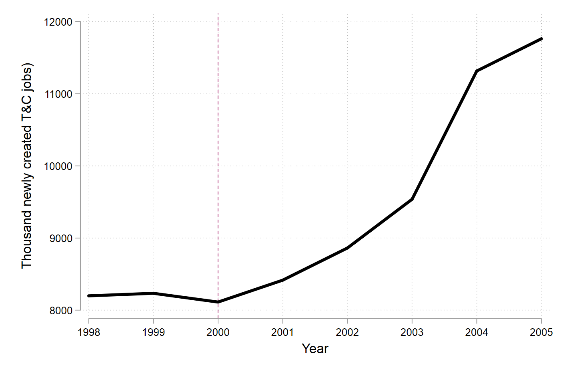

The MFA, a nontariff barrier, imposed export quotas to limit T&C exports to rich-country markets. However, the Agreement on Textile and Clothing (ATC) replaced the MFA during the Uruguay Round in 1995, marking a significant step toward global trade liberalization. China became eligible for ATC integration in late 2001, following its admission to the World Trade Organization. After being admitted to the WTO, China dramatically expanded its T&C exports to high-income countries (Figure 1), leading to a substantial increase in T&C sector employment (Figure 2).

Figure 1: T&C Exports by Destinations

Figure 2: Evolution of T&C employment,1998–2005

The expansion of T&C exports to high-income markets increased the demand for skills needed to produce, design, and sell higher-quality T&C goods. A simple comparison of the changes in workers with at least a high school education shows that the number of purchasing and sales workers with at least a high school education increased by 5.69 million from 2000 to 2005. However, the number of T&C production line workers increased by only around 0.227 million over the same period. This disproportionate surge suggests that the expansion of T&C employment led to higher demand for medium-level skilled workers relative to unskilled ones, which could encourage households to invest more in children’s education.

What we learned from destination-specific export expansions

In a recent study by Zhang and Zhou (2023), a unique dataset was used to explore the short-run schooling consequences and long-term effects of destination-specific export expansions following the end of the MFA. The identification strategy leverages the timing of the MFA's end and the export exposures experienced by 16-year-olds. In China, age 16 marks the typical end of nearly free compulsory education and is the first age at which youths are legally allowed to enter local labor markets according to Chinese labor laws. Therefore, it is a critical age for households deciding whether to send pupils to costly high school. Our study compares the outcomes of cohorts exposed to varying levels of local export shocks at age 16.

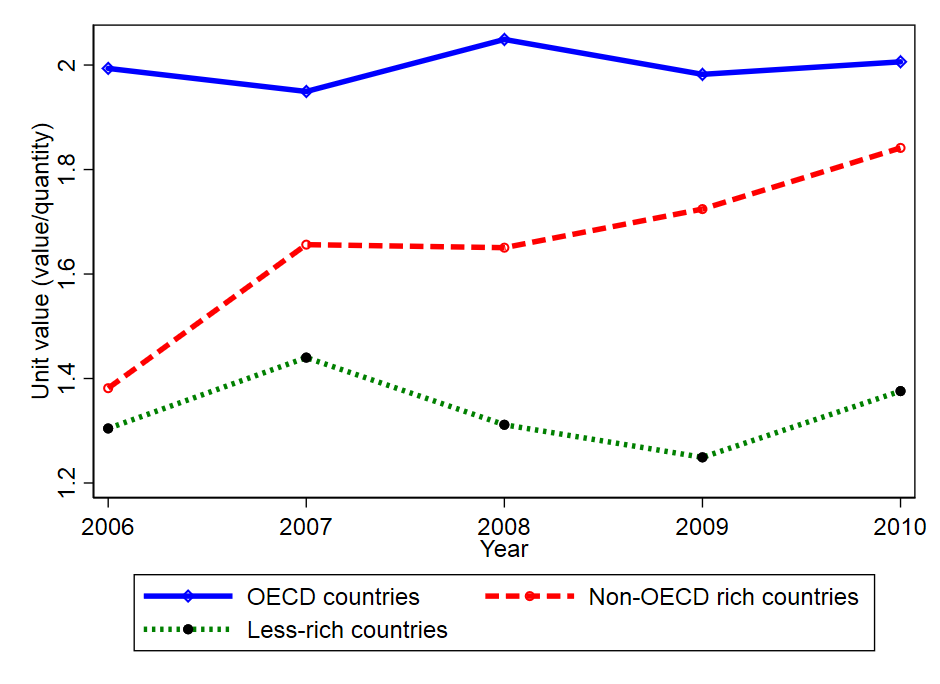

Our empirical evidence suggests that the expansion of MFA exports to high-income countries increased high school enrollment rates. This was driven by both household income growth and the local education premium. Our analysis of the income effect restricts the sample to the T&C industries, and the evidence suggests that more exposed prefectures increased T&C production more to boost exports and consequently employment in these industries. Yet, this growth does not necessarily translate into overall income and employment gains for the prefectures, as output and employment in other industries at a comparative disadvantage may simultaneously decline under balanced trade conditions. Despite the potential for simultaneous reductions under balanced trade, China’s trade is unbalanced over the period, and the aggregate trade surplus expanded rapidly, driven mainly by exports to rich countries, including the MFA good (Brambilla, Khandelwal, and Schott, 2010). Furthermore, we provide evidence of the education premium as another mechanism. As detailed in the paper, we find a rise in local skill demand induced by the expansion of exports to high-income countries, where consumers prefer higher-quality products (Figure 3). Consequently, exporting to rich countries increases the demand for local skill embodied in exports.

Figure 3: Unit value of T&C goods exported to different countries, 2006–2010

We find also unequal effects of the expansions across genders, regions, and the rural-urban divide. MFA export expansions slightly favored girls, consistent with the argument that a change in gender-specific income affects the relative outcomes for the gender (Voigtländer and Voth 2013; Schaller 2016). This effect was more pronounced in urban areas, where households were more likely to perceive changes in education returns. Moreover, this impact was more pronounced in regions with initially scarce skills, suggesting that the initial skill endowment influenced the schooling consequences of exports.

Tracking the affected cohorts to examine longer-run effects

We tracked the affected cohorts for 10 to 15 years to assess the longer-run effects, including the completion of higher education and various adult outcomes. We find that the increased high school enrollment rates translated into higher high school attainment. However, the impact on college education was small and statistically insignificant, suggesting that the T&C export shocks resulted in only a medium-level increase in skill acquisition.

In terms of labor market outcomes, we find that individuals exposed to larger MFA export shocks at age 16 were less likely to be unemployed or exit the labor market in 2015. They were also more likely to migrate between prefectures and tended to delay having children. These findings highlight the long-lasting effects of early-life export shocks on adult outcomes.

Why households responded to T&C export expansions

Our theoretical framework proposes wage growth and education premium as the main channels driving the observed outcomes. Our evidence supports these mechanisms, showing that households exposed to larger MFA export expansions invested more in their children’s education. This was driven by increased household incomes and a higher education premium in local labor markets.

These findings suggest that the preference of rich-country markets for higher-quality products enhances human capital investment in the source country and the enhancement works mainly through an increase in households’ educational investment, driven by a mechanism involving wage growth and high school education premium in local labor markets.

Conclusion

Our findings underscore the importance of considering the destination-specific nature of exports when evaluating the impact of trade liberalization. Exporting to high-income countries, where there is a preference for higher-quality goods, can enhance human capital investment in the source country. This has important policy implications for developing countries that rely heavily on exports of low-technology goods but struggle to upgrade the skills level of their workforce.

Authors’ note: This research was made possible by the support of the Major Program of the National Social Science Fund of China and the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

(Junsen Zhang, Zhejiang University; Kang Zhou, Zhejiang University)

References

Atkin, David. 2016. “Endogenous Skill Acquisition and Export Manufacturing in Mexico.” American Economic Review 106 (8): 2046–85. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120901.

Brambilla, Irene, Amit Khandelwal, and Peter K. Schott. 2007. “China’s Experience under the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA) and the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC).” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 13346. https://doi.org/10.3386/w13346.

Li, Bingjing. 2018. “Export Expansion, Skill Acquisition, and Industry Specialization: Evidence from China.” Journal of International Economics 114: 346–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.07.009.

Schaller, Jessamyn. 2016. “Booms, Busts, and Fertility: Testing the Becker Model Using Gender-Specific Labor Demand.” Journal of Human Resources 51 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.51.1.1.

Voigtländer, Nico, and Hans-Joachim Voth. 2013. “How the West ‘Invented’ Fertility Restriction.” American Economic Review 103 (6): 2227–64. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2227.

Zhang, Junsen, and Kang Zhou. 2023. “Quota Removal, Destination-Specific Export Shocks, and Skill Acquisition in China.” Journal of Development Economics 165: 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103149.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email