Fertility and Delayed Migration: How Son Preference Protects Young Girls Against Mother–Child Separation

Mother–child separation harms children’s development. This concern is particularly relevant in rapidly urbanizing societies with massive migration. We find that during early childhood, specifically at age two, girls are less likely to become separated from their parents than boys in rural China. This is due to son preference, which leads parents to attempt to have another child after a firstborn daughter, mostly when the daughter is two years old. Furthermore, migrant women often stay in their hometowns during pregnancy, which paradoxically prevents mother–daughter separation.

Early childhood experiences establish the foundation for optimum health, growth, and neurodevelopment throughout the lifespan (Cunha et al. 2006; Heckman 2006; Cunha and Heckman 2007; Cunha, Heckman, and Schennach 2010). Parental companionship, especially from one’s mother, plays a critical role in building this foundation (Baum 2003; Zhao et al. 2014; Luby et al. 2016). However, knowledge of who is more likely to experience this separation and why is rather lacking. This question is particularly relevant for countries that have undergone rapid urbanization. In China, when workers migrate to more developed regions, they often leave their children behind in their hometowns owing to high childcare costs or limited access to public schools and kindergartens in urban areas (Graham and Jordan 2011; Zhang et al. 2014).

In this study, we aim to answer an important question: Is there a gender gap in being left behind during early childhood? If so, what is the mechanism? We find that parents are less likely to leave girls behind than boys in early childhood in rural China and this gap can be paradoxically explained by mothers’ tendency to stay at home to give birth to the second child if the first child is a girl, due to son preference.

Previous studies have investigated human capital losses of left-behind children from different perspectives (Chen 2013; Zhang et al. 2014; Meng and Yamauchi 2017) and the existence of the son preference in various countries (Park and Cho 1995; Das Gupta et al. 2003; Ebenstein 2010). We extend the literature by investigating the gender gap in mother-child separation and find a surprising mechanism where son preference protects young girls. We also offer a new explanation for the puzzling phenomenon in which, on average, girls perform better academically than boys (Entwisle 2018).

General Findings

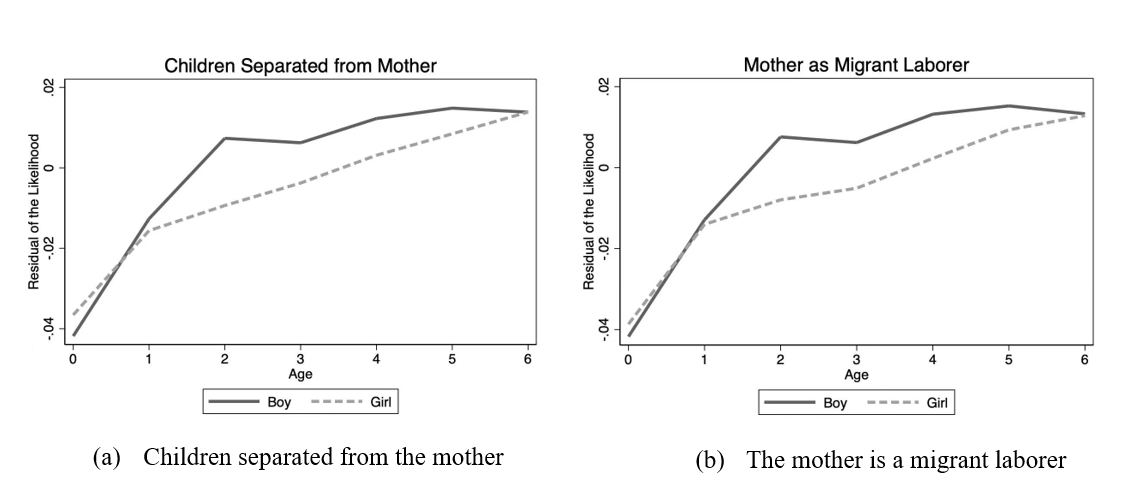

Using the population census in 2010, we draw two figures on the gender difference in the probability of mother-child separation and mother’s migration for work in Figure 1. The sample comprises children ages zero to six from rural Han families, excluding those migrating with parents. Provinces under a restrictive one-child policy or with large minority groups are also excluded. The horizontal axis is the children’s age. In subfigure (a), the vertical axis represents the likelihood of mothers currently residing in a different county, after netting out family characteristics, including parents’ ages (and the quadratic terms), the dummy indicator of rural residency in the hukou system, and parents’ years of schooling. In subfigure (b), the vertical axis denotes the likelihood of mothers currently migrating for work for children of certain age, after netting out family characteristics. Figure 1 clearly shows that boys are more likely to suffer from mother-child separation and have a migrant mother during early childhood, especially at age two. Using a difference-in-differences regression, we show that boys are 3.1 percentage points more likely to be separated from their mothers than girls at age two. This is equivalent to a 44.9 percent increase in the probability of separation. In line with this result, we find the likelihood of parents, especially mothers, migrating for work to be significantly higher for boys than for girls at age two.

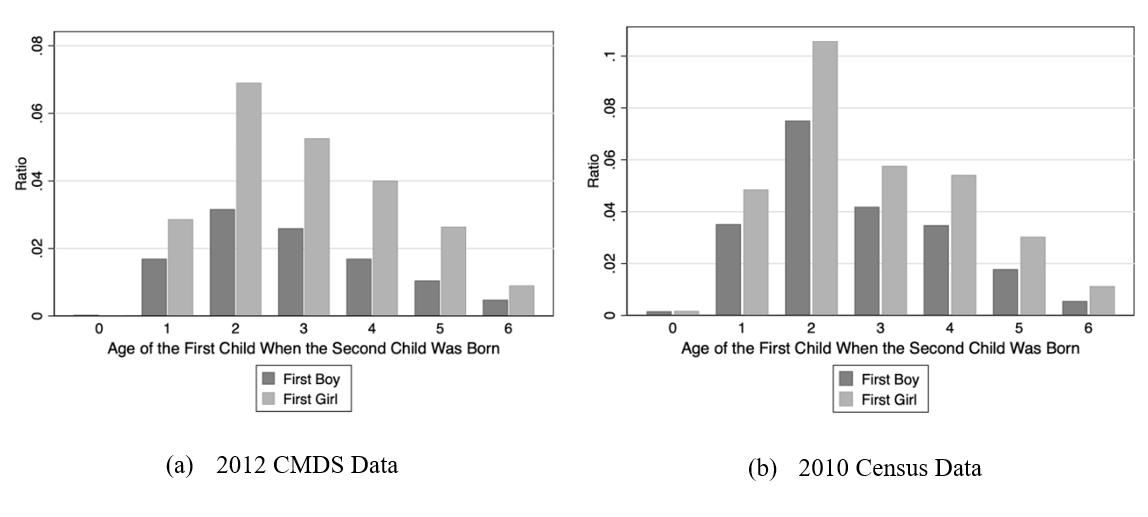

To explain the observed gender gap, we further collect two pieces of evidence. First, we find that families with firstborn girls are much more likely to give birth to a second child, and the birth peak is two years after the first baby. We depict the ratio of the number of families who have second children to the total number of families that already have one child by birth interval and firstborn gender in Figure 2. Subfigure (a) uses data from the 2012 wave of the China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS), which is implemented by the National Health Commission and targets migrant households, and subfigure (b) uses the 0.35% sample from the 2010 China Population Census. Both samples consist of rural Han families with migrant parents, excluding province of origin under a restrictive one-child policy or with large minority groups. On the one hand, Chinese parents are, on average, 11.9 percentage points (110.7%) more likely to give birth to a second child when their firstborn is a girl. This finding is consistent with much of the prior research documenting the impact of son preference on fertility (Ebenstein 2010). On the other hand, the peak timing for migrant parents to give birth to a second child is two years after the first birth.

Second, we find that pregnant women postpone migration or return to their hometowns when they are pregnant and preparing for childbirth. The CMDS suggests that 64.2% of migrant mothers stay in their hometowns throughout their pregnancy; 80.9% give birth in their hometowns. Due to the dual hukou system, rural residents are ineligible for urban health insurance, which makes parents to give birth to babies in their hometowns.

Figure 1. Residual of the likelihood of mother-child separation and that of mother being migrant laborer against children’s age.

Source: 0.35% sample from the 2010 China Population Census.

Figure 2. Ratio of the number of households giving birth to a second child to the total number of households with at least one child.

Subfigure (a) uses data from the 2012 wave of the CMDS, and subfigure (b) uses the 0.35% sample from the 2010 China Population Census. The dark bars indicate households with firstborn boys, while the light bars represent households with firstborn girls.

Combining the evidence of the likelihood, timing, and location of a mother’s second experience of childbirth, we argue that the gender gap in mother-child separation during early childhood is driven by the fact that, in the context of son preference, parents with firstborn girls are more likely to have a second child shortly after their first child’s birth (Ebenstein 2010). The fact that pregnant women postpone migration or return to their hometowns effectively prevents mother–daughter separation until the mother gives birth to her second child, which is around the time when her firstborn turns two years old. Thus, son preference paradoxically protects girls from becoming separated from their mothers in early childhood.

We investigate the above-mentioned mechanism by two placebo tests. First, during the 1980s and 1990s, in some provinces, even if a second birth was permitted, women could only give birth to a second child four years or more after the birth of the first child (e.g., Gansu, Hubei, and Jiangxi). We illustrate that gender differences in early childhood separation do not exist in these regions with birth interval restrictions, as parents cannot freely respond to the birth of a firstborn girl by immediately having a second child. Second, we note that the observed gender gap in early childhood separation occurs only in provinces with a 1.5 or two-child policy, but not in provinces with a strict one-child policy because families are not permitted by law to respond to the birth of a firstborn girl by having a second child. To further examine this mechanism, we conduct two heterogeneity analyses. First, we detect a significant gender difference in being left behind only in regions with skewed sex ratios and in families with lower levels of parental education. Second, we find that gender differences in parent–child separation are more prominent in regions with high historical migration rates.

Policy Implications

People usually consider girls to be vulnerable in China due to son preference. However, we show that boys are also victims of son preference. In a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation, we show that 5% to 20% of the gender gap in academic performance in elementary school can be attributed to the gender gap in mother-child separation at age two. Thus, our study has an important policy implication to call for a protection for not only girls, but also boys in their first 1,000 days when they may suffer from being left behind by their migrant parents. A more promising way to address this issue and the problem of left-behind children in general would be for policymakers to remove barriers to social services in different localities, which would allow parents to be with their children while pursuing better work opportunities.

(Zibin Huang, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics; Xu Jiang, Renmin University of China; Ang Sun, Renmin University of China)

References

Baum II, Charles L. 2003. “Does Early Maternal Employment Harm Child Development? An Analysis of the Potential Benefits of Leave Taking.” Journal of Labor Economics 21 (2): 409–448. https://doi.org/10.1086/345563.

Chen, Joyce J. 2013. “Identifying Non-cooperative Behavior Among Spouses: Child Outcomes in Migrant-Sending Households.” Journal of Development Economics 100 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.06.006.

Cunha, Flavio, James J. Heckman, Lance Lochner, Dimitriy V. Masterov. 2006. “Interpreting the Evidence on Life Cycle Skill Formation.” In Handbook of the Economics of Education, vol. 1, edited by Eric Hanushek and Finis Welch, 697–812. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Cunha, Flavio, and James Heckman. 2007. “The Technology of Skill Formation.” American Economic Review 97 (2): 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.2.31.

Cunha, Flavio, James J. Heckman, and Susanne M. Schennach. 2010. “Estimating the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Formation.” Econometrica 78 (3): 883–931. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA6551.

Das Gupta, Monica, Jiang Zhenghua, Li Bohua, Xie Zhenming, Woojin Chung, and Bae Hwa-Ok. 2003. “Why Is Son Preference So Persistent in East and South Asia? A Cross-Country Study of China, India, and the Republic of Korea.” Journal of Development Studies 40 (2): 153–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293807.

Ebenstein, Avraham. 2010. “The ‘Missing Girls’ of China and the Unintended Consequences of the One Child Policy.” Journal of Human Resources 45 (1): 87–115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2010.0003.

Entwisle, Doris R. 2018. Children, Schools, and Inequality. Routledge. New York: Routledge.

Graham, Elspeth, and Lucy P. Jordan. 2011. “Migrant Parents and the Psychological Well-Being of Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73 (4): 763–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00844.x.

Heckman, James J. 2006. “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children.” Science 312 (5782): 1900–1902. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128898.

Luby, Joan L., Andy Belden, Michael P. Harms, Rebecca Tillman, and Deanna M. Barch. 2016. “Preschool Is a Sensitive Period for the Influence of Maternal Support on the Trajectory of Hippocampal Development.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (20): 5742–47. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601443113.

Meng, Xin, and Chikako Yamauchi. 2017. “Children of Migrants: The Cumulative Impact of Parental Migration on Children’s Education and Health Outcomes in China.” Demography 54 (5): 1677–1714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0613-z.

Park, Chai Bin, and Nam-Hoon Cho. 1995. “Consequences of Son Preference in a Low-Fertility Society: Imbalance of the Sex Ratio at Birth in Korea.” Population and Development Review 21 (1): 59–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137413.

Potter Jr., Robert G. 1963. “Birth Intervals: Structure and Change.” Population Studies 17 (2): 155–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.1963.10405762.

Zhang, Hongliang, Jere R. Behrman, C. Simon Fan, Xiangdong Wei, and Junsen Zhang. 2014. “Does Parental Absence Reduce Cognitive Achievements? Evidence from Rural China.” Journal of Development Economics 111: 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.09.004.

Zhao, Qiran, Xiaohua Yu, Xiaobing Wang, and Thomas Glauben. 2014. “The Impact of Parental Migration on Children’s School Performance in Rural China.” China Economic Review 31: 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2014.07.013.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email