Does Farming Culture Shape Household Financial Decisions?

The study investigates the impact of traditional rice farming culture on household financial decisions in China. It finds that the collectivist culture associated with rice farming leads to a higher propensity for stock market investment and lottery ticket purchases, while reducing the purchase of insurance. This behavior is attributed to strong community ties and informal safety nets that reduce perceived financial risks. The research highlights the significant influence of cultural heritage on modern economic behaviors and the importance of considering cultural factors in financial policymaking.

For a household in modern society, investing in financial markets is important, as it contributes to asset accumulation, welfare growth, and consumption smoothing (Cole and Shastry 2009). Regardless of the household’s level of risk aversion, its investment in risky assets should be greater than zero (Campbell 2017). While the literature extensively describes the benefits of investing in financial markets, the data tell a different story: in China, only 14.8% of households invest in the financial markets.

Our study (Zeng and Yu 2024) explores how ancient farming culture affects investment decisions in Chinese households. The recent development of the rice theory of culture (Talhelm et al. 2014) allows for the measurement of collectivist versus individualist culture variations within China. The theory posits that people in regions with a long history of growing rice are more collectivist than those in wheat-growing regions because paddy rice requires more intensive irrigation and labor compared to wheat, necessitating more cooperative work with a farmer's family members and neighboring farmers. Based on this, we propose that rice farming culture is a cultural factor that contributes to households’ ability to cope with financial distress. We postulate that households in regions with stronger rice farming cultures will have a more effective informal risk diversification system and therefore a greater ability to cope with potential future financial distress. As a result, they will be more willing to invest in financial markets and buy lottery tickets. Additionally, this informal risk diversification system can act as a substitute for insurance, leading to lower demand for insurance among residents of these areas.

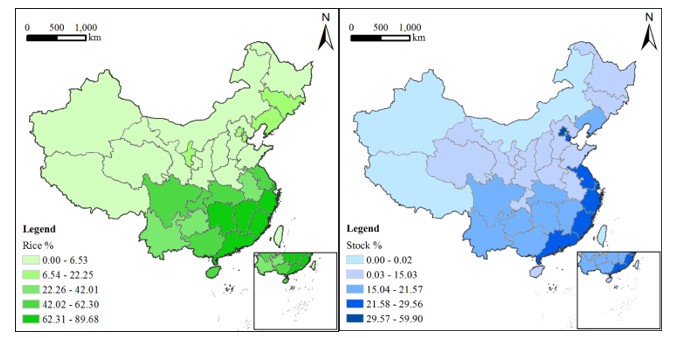

Figure 1 shows the ratio of rice area to arable land and the number of stock accounts to the total population for each province in China. Provinces with a higher proportion of rice cultivation have a higher proportion of their population with stock accounts.

Figure 1. Rice cultivation and household stock holdings in China

The map on the left shows the distribution of rice cultivation in China, with darker colors indicating a higher proportion of rice cultivation in that region. The map on the right shows the distribution of stock market investment in China, with darker colors indicating a higher proportion of residents in the region with a stock account.

From the data of financial decisions in more than 90,000 Chinese households, as shown in Figure 2, we find that those in regions with a history of rice cultivation are more inclined to participate in the stock market (44% higher than the average) and purchase lottery tickets (65% higher than the average). Yet, these households show less interest in purchasing insurance (12% lower than the average). This could be attributed to the community itself acting as a safety net, a form of living insurance woven from bonds of mutual assistance. This propensity reflects the communal risk-taking culture of their ancestors.

Figure 2. Household stock holdings, risky financial assets, insurance, and lottery tickets in rice and wheat regions

Figure 2 shows the proportion of households in rice and wheat regions holding stocks and risky financial assets, and buying insurance or lottery tickets. The criterion for distinguishing between rice and wheat regions is whether the area under rice cultivation accounts for 50% of the area being put to agricultural use; if rice cultivation exceeds 50% of agricultural land usage, then the province is classified as a rice region, and vice versa. Whiskers in the graph represent the 95% confidence interval for the statistics.

To address potential confounding factors, we run a series of tests to ensure that the observed financial behaviors are attributed to culture rather than regional economic prosperity, government policies, or other socioeconomic variables.

First, we adopt Talhelm et al.’s (2014) approach by using a subsample of households from neighboring counties on different sides of the Qinling-Huaihe Line, the historic geographic rice-wheat border of China. This line spans five provinces and separates the rice-growing regions from the wheat-growing regions. Within the same province, households on either side of the line are likely to be affected by similar regional factors but have vastly different farming methods. By focusing on households in the Qinling-Huaihe Line regions, we can mitigate the impact of other potential regional factors. Secondly, we use instrumental variables such as rainfall patterns, which serve as proxies for the intensity of rice cultivation, thus strengthening the validity of the findings. Finally, in all the tests, we control for regional GDP per capita and disposable income per capita to isolate the effect of rice culture from mere economic development.

To explore the potential mechanism of the rice effect, we found that households in rice-growing regions are more likely to borrow from friends and relatives and have interest waived. With the increased accessibility of informal credit, households in collectivist cultural areas encounter weaker financing constraints and are more inclined to take risks.

We also investigate the relationship between rice farming culture and the development of regional clan systems, and find that clan systems contribute to the formation of local business alliances and thus promote business development at the local level as Cai, Zhou, and Wu (2008) suggest. We find that business development at the end of the Qing Dynasty was also one of the important channels through which collectivist culture influenced household financial decisions.

In addition, we find that people in areas with a stronger rice farming culture have greater trust in others. More trusting individuals perceive a lower probability of being cheated and thus are less reluctant to invest in financial markets (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales 2008). We also find that where more rice is grown, there is also higher social capital, which affects the willingness of residents to make risky investments.

We also find the link between collectivist culture and cognitive biases related to prospect theory. Households that are more influenced by collectivist culture have risk preferences that are better predicted by prospect theory. This finding may help explain investors’ behaviors in the financial markets with rice-cultivation origins.

Collectivist culture based on rice cultivation plays an important role as an informal system of risk diversification by enhancing the factors as explained above. This influence is so long-lasting and far-reaching that urban residents, despite having long ago moved away from agricultural activities, are unable to escape it. Our decisions today have been shaped partly by our ancestors who planted seeds in the fields two thousand years ago.

References

Cai, H. B., L. A. Zhou, and Y. Y. Wu. 2008. “Clan System, Merchant Beliefs and Merchant Governance: A Comparative Study of Huizhou and Jin Merchants in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.” Management World (8): 87–99. (In Chinese)

Campbell, John Y. 2017. Financial Decisions and Markets: A Course in Asset Pricing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cole, Shawn, and Gauri Kartini Shastry. 2009. “Smart Money: The Effect of Education, Cognitive Ability, and Financial Literacy on Financial Market Participation.” Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/smart-money-the-effect-of-education-cognitive-ability-and-financial-literacy-on-financial-market-participation.

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales. 2008. “Trusting the Stock Market.” Journal of Finance 63(6), 2557–2600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2008.01408.x.

Talhelm, Thomas, Xuemin Zhang, Shigehiro Oishi, Shimin Chen, Dongyuan Duan, Xuezhao Lan, and Shinobu Kitayama. 2014. “Large-Scale Psychological Differences within China Explained by Rice versus Wheat Agriculture.” Science, 344 (6184): 603–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246850.

Zeng, Sipeng, and Frank Yu. 2024. “Does Farming Culture Shape Household Financial Decisions?” Journal of Corporate Finance 84: 102533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2023.102533.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email