Fiscal Stimulus, Deposit Competition, and the Rise of Shadow Banking: Evidence from China

Shadow banking—the unregulated or lightly regulated non-bank segment of the financial sector lacking an explicit safety net—has evolved into a significant fraction of the overall financial system in both developed and emerging market economies. IMF (2014) notes that under some measures, shadow banking grew before and after the global financial crisis (GFC), and its growth outpaced that of the traditional banking system. Understanding the causes and consequences of its growth is thus an important question for academia, policy, and practice.

The extant literature has focused on monetary policies and on private incentives to “arbitrage” bank regulation as the main factors that lead to the rise of shadow banking. For example, Xiao (2020) finds that deposits will flow out of traditional banking to the shadow banking sector during periods of tightening monetary policies. Buchak et al. (2018) and Gopal and Schnabl (2022) show that the aftermath of the GFC and a tightening of bank regulations led to a contraction of bank credit, and shadow banks, including online, “fintech” lenders, partially filled the gap. Hachem and Song (2021) show that the tightening of liquidity regulations can push banks facing a liquidity crunch to issue more shadow banking products, leading to a possible reallocation of funding away from more liquid banks. Within the banking system, shadow banking can also arise in the form of regulatory arbitrage that leads to securitization without risk transfer (Acharya et al. 2013a, 2013b; Borst 2013).

In contrast to prior literature, we show in our recent paper, entitled “Fiscal Stimulus, Deposit Competition, and the Rise of Shadow Banking: Evidence from China,” that large-scale fiscal policies can also give rise to rapid growth of the shadow banking sector. Conceptually, fiscal policies supported by credit expansion can intensify deposit competition, which will not only increase deposit rates and reduce bank profits, but also drive banks to other funding sources as they seek to maintain profitability. One way to maintain profitability is to issue off-balance-sheet, shadow-banking products. The increasing reliance on these less-regulated products can have an adverse impact on the entire banking sector. This new perspective, along with empirical evidence, differs from the extant literature in terms of the source of the shock (fiscal expansion versus monetary tightening) and banks’ motivation for issuing shadow-banking products (profit-seeking versus circumventing regulations).

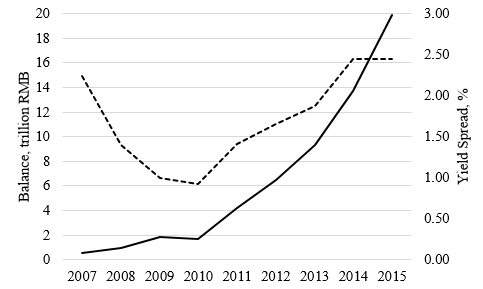

We examine how this new mechanism affects the banking sector by studying the RMB 4 trillion fiscal stimulus in China following the GFC. Large, state-owned banks supported the fiscal stimulus by issuing a large volume of new loans during 2009–10. The GFC also slowed bank deposit growth from cross-border money inflows. We focus on wealth management products (WMPs), which are investment products offered by banks to depositors, with either explicit or implicit return guarantees and not subject to on-balance sheet regulations such as those for deposits. Figure 1 shows that both the size of bank WMPs and their yield spread (yield over deposit rate ceiling) quickly increased after 2010, suggesting a swift increase in WMP supply from banks.

Figure 1. Balance (solid curve) and Yield Spread (dashed curve) of bank WMPs

To establish a causal relationship between intensified deposit competition and the rise of WMPs, we exploit the unique role of a large, state-owned bank, Bank of China (BOC). Compared to other large banks, BOC was much more aggressive in its credit expansion. From 2008 to 2010, loan balance increased by 77% for BOC, as compared to 60% for Agricultural Bank of China, 48% for both the China Construction Bank and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and 59% for all banks as a whole. In the meantime, BOC also suffered disproportionately large losses in foreign deposit inflows due to its predominant role in China’s international settlement market. Starting in 2011, when the stimulus ended and tightening monetary policy ensued, BOC competed more aggressively for deposits (to maintain the regulatory limit of loan-to-deposit ratio). While all the big banks offered almost the same deposit rates before 2010, the deposit rate offered by BOC began to diverge from the other big banks and remained higher by about 0.3%. Given the size of BOC in local deposit markets, the increased competition had a material impact on the small and medium-sized banks (SMBs). We then use the branch overlap with BOC as a measure of intensified deposit competition for SMBs after 2010 and study the responses of SMBs.

Consistent with the deposit competition hypothesis, branch overlap with BOC has a significant and negative impact on the SMBs’ deposit availability, as measured by the deposit-to-asset ratio (DAR), and a significant and positive impact on their WMP issuance. A one-dollar loss in deposits is estimated to lead to a one-dollar increase in WMP balance.

Besides WMPs, intensified deposit competition also increases the banks’ deposit rates, WMP yields, and interbank borrowing and bond financing, but there is no significant effect on other passive liabilities from their business operation. In terms of magnitude, the loss of deposits induced by BOC competition is fully compensated by the increase in interbank borrowing and bond financing. As a result, we find no significant impact of deposit competition on the SMBs’ on-balance-sheet assets.

If the SMBs can fully make up the loss of deposits with other on-balance-sheet liabilities, why do they still issue WMPs? We propose that short-term profit-seeking as the main motive. As SMBs increase their deposit rates and shifted to costlier funding sources (e.g., interbank borrowing and bond financing), their profitability is significantly and negatively impacted. When the exposure to BOC competition increases from the 10th to the 90th percentile, the average ROA (return on assets) decreases by 0.2% (compared to the sample mean of 0.9%) and ROE (return on equity) decreases by 3.0% (compared to the sample mean of 12.5%). Profits from off-balance sheet activities can partially make up, roughly by one quarter, the total losses due to more fierce deposit competition. This profit-seeking motive is similar to the practice of “reaching for yield” in the asset management industry: fund managers sometimes take on excessive, unmeasured risks when fund performance is evaluated based on measured risks. Similarly, banks seek profits from off-balance-sheet activities, which are not regulated and evaluated as on-balance-sheet activities.

The shift from deposit to WMP financing can have a substantial impact on bank risks. Meiselman, Nagel, and Purnanandam (2023) show with empirical evidence that banks’ short-term profit-seeking strategy is in general associated with greater realization of tail risks. In our context, the issuance of WMPs can expose banks to greater rollover risks, since WMPs have a shorter maturity (typically three to six months) than average deposits.

We find several pieces of evidence suggesting increased rollover risks as a result of more WMP outstanding. First, a greater number of WMPs due is associated with higher yields on the new products, suggesting that banks use new products to roll over maturing products. Second, banks ask for significantly higher quotes in the interbank market when they have more WMPs approaching maturity. At the aggregate level, the one-week Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (SHIBOR) closely tracks the aggregate amount of maturing WMPs. Finally, investors appear to “price” the banks’ rollover risks: during episodes of interbank market distress, stock prices drop more for banks with more WMPs approaching maturity in the short run.

(Viral V. Acharya, Stern School of Business, New York University; Jun “QJ” Qian, International School of Finance, Fudan University; Yang Su, Business School, Chinese University of Hong Kong; Zhishu Yang, School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University)

References

Acharya, Viral V., and R. Sabri Öncu. 2013a. “A Proposal for the Resolution of Systemically Important Assets and Liabilities: The Case of the Repo Market.” International Journal of Central Banking 9 (1): 291–350. https://www.ijcb.org/journal/ijcb13q0a14.pdf.

Acharya, Viral V., Jun Qian, Yang Su, and Zhishu Yang. 2023. “Fiscal Stimulus, Deposit Competition, and the Rise of Shadow Banking: Evidence from China.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32034.

Acharya, Viral V., Philipp Schnabl, and Gustavo Suarez. 2013b. “Securitization without Risk Transfer.” Journal of Financial Economics 107 (3): 515–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.09.004.

Borst, Nicholas. 2013. “Shadow Deposits as a Source of Financial Instability: Lessons from the American Experience for China.” Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Briefs 13–14. https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/shadow-deposits-source-financial-instability-lessons-american-experience.

Buchak, Greg, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru. 2018. “Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise of Shadow Banks.” Journal of Financial Economics 130 (3): 453–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.03.011.

Hachem, Kinda, and Zheng Song. 2020. “Liquidity Rules and Credit Booms.” Journal of Political Economy 129 (10): 2721–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/715074.

Gopal, Manasa, and Philipp Schnabl. 2022. “The Rise of Finance Companies and FinTech Lenders in Small Business Lending.” Review of Financial Studies 35 (11), 4859–901. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhac034.

International Monetary Fund, 2014. “Risk Taking, Liquidity, and Shadow Banking: Curbing Excess While Promoting Growth,” Global Financial Stability Report. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2016/12/31/Risk-Taking-Liquidity-and-Shadow-Banking-Curbing-Excess-While-Promoting-Growth.

Meiselman, Ben S., Stefan Nagel, and Amiyatosh Purnanandam. 2023. “Judging Banks’ Risk by the Profits They Report.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 31635. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31635.

Xiao, Kairong. 2020. “Monetary Transmission through Shadow Banks.” Review of Financial Studies, 33 (6): 2379–420. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz112.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email