Reluctant Entrepreneurs: Evidence from China’s SOE Reform

In this column, we examine how the presence of state-owned enterprises (SOE) affects the private sector by influencing the allocation of skills across SOEs, private sector waged employment and entrepreneurship. The allure of state-sector employment for high-skilled labor not only discourages the growth of the private sector through labor allocation but, more importantly, impedes the establishment of new productive private firms, thus reducing the dynamism of the economy. However, once these high-skilled individuals are compelled to exit the SOEs---for example, due to the large-scale SOE downsizing that occurred in China in the late 1990s---they reluctantly transform into successful entrepreneurs who catalyze the economic growth in subsequent decades.

Entrepreneurship is one of the core engines for economic growth, fostering innovation, and generating employment opportunities (Haltiwanger et al., 2013; Decker et al., 2014). Firms founded by entrepreneurs with higher skills tend to exhibit greater growth throughout their life cycles, and are the key drivers for economic dynamism (Queiró, 2022). However, the conventional wisdom that individuals with the greatest ability naturally gravitate toward entrepreneurship has been challenged in recent papers (Hacamo and Kleiner, 2022; Bai et al., 2021). Indeed, a Roy-style career choice model would have predicted that individuals with the greatest ability do not necessarily gravitate towards entrepreneurship when alternative employment options offer attractive features such as social status, job security, and social welfare provisions, which they may value more than low-skilled workers. Often, high-skilled individuals become entrepreneurs reluctantly, i.e. not out of a strong desire or passion for entrepreneurship, but out of necessity or other circumstances.

In our recent paper (Fang et al. 2023), we study the impact of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) on the quality of entrepreneurship in China. China provides an ideal setting to study the impact of SOEs on entrepreneurship. The share of SOEs in the Chinese economy has experienced dramatic changes since the 1990s. The number of state-owned or state-controlled enterprises fell from 118,000 in 1995 to 24,961 in 2004. Official data suggests that China laid off about 35 million SOE workers between 1995 and 2001, particularly during the SOE downsizing of 1998 when China was preparing for its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). The unprecedented event enables us to study not only changes in the sorting of individuals who just enter the labor market, but also the reshuffling of high-ability individuals---who initially sorted into the state sector before the SOE reform---reluctantly into entrepreneurship.

The allure of the state sector has become even more relevant nowadays. Starting from 2013, there has been a resurgence of SOE in the Chinese economy (Fang et al., 2022; Brandt et al., 2023) and thus understanding the impact of SOE on entrepreneurship is again crucial for predicting the future dynamism of the Chinese economy.

SOE’s Benefits and Individuals’ Occupational Choice

Despite the fact that SOEs have lower productivity than private-owned enterprises (POEs), extensive literature documents that SOEs have better access to economic resources, and SOE employees enjoy superior job-related benefits than those of POEs or the self-employed. Because no doubt individuals value these benefits, the availability of SOE employment is likely to affect who select into entrepreneurship.

We first develop a simple three-sector occupational choice model to illustrate how individuals with different entrepreneurial abilities select into three sectors: working for an SOE firm; working for a POE firm; and becoming an entrepreneur. If the individual becomes an SOE worker, he receives a constant wage as well as additional benefits---e.g., job security, fringe benefit, and social status; if he works for a POE firm, he receives a constant wage plus a bonus payment that depends on his ability; if he becomes an entrepreneur, he is endowed with a project and exerts effort to search for an alternative riskier project with a higher payoff, where the cost of effort decreases with his entrepreneurial ability.

The model predicts that, if individuals with a higher entrepreneurial ability tend to value more the benefits/amenities associated with the SOE jobs, then the most able individuals will selected into the SOE sector, the moderately able individuals into the entrepreneurial sector, and the least able individuals into the POE sector. We provide supportive evidence, using the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) survey data, for the ability ranking among the three sectors as predicted by our model prior to the 1998 SOE downsizing.

SOE Reform: Worsening Job Prospects (1992-1997), Massive Layoffs (1998-2001), and the Burgeoning of Reluctant Entrepreneurs

Following Deng Xiaoping's South Tour in 1992, a spectrum of liberalization policies were adopted to reform the SOE sector and establish a modern enterprise system. Crucially, the reform introduced market competition against SOEs and harbingered a vibrant private sector (Garnaut et al., 2018; Naughton, 1994). The reform from 1992 significantly worsened the prospect of SOE jobs by lessening the government support for the SOEs, though they continued to operate at loss. Crucial for our model of individuals’ sectoral choice, the “guaranteed job assignment” system for college graduates was revoked from 1992, and college graduates were highly encouraged to seek job opportunities on their own, including in the private sector.

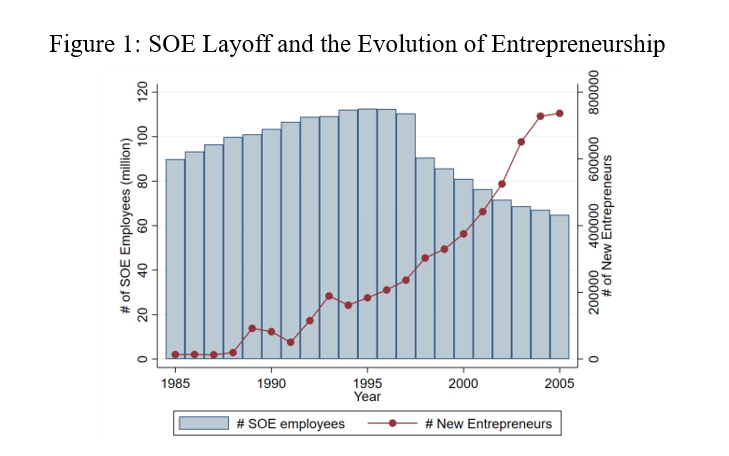

From 1998, China initiated a major SOE reform, known as the “Grasp the Large, Let Go of the Small'' policy, which was announced at the 15th CCP Congress (Hsieh and Song, 2015). The key component of the policy is to keep only a few large SOEs in the strategic sectors and to merge, privatize, and close most other medium-to-small SOE firms. This led to a substantial downsizing of the SOE labor force. In the post-layoff era, there was a remarkable increase in the number of private firms and new entrepreneurs. Figure 1 shows that the number of SOE employees experienced a sharp decline since 1998, and the number of new entrepreneurs experienced rapid growth.

Notes: This figure plots the evolution of entrepreneurship in corresponds to the evolution of SOE layoff. The left axis corresponds to the number of SOE employees, and the right axis corresponds to the number of new entrepreneurs in each year. It shows that the number of new entrepreneurs that enters the market each year were stable (around 4,000 per year) in the early 1990s, and has been growing rapidly and more than doubled till 2005.

Reluctant Entrepreneurs Perform Better

More importantly, as the average entrepreneurial ability of SOE workers is higher than that in the entrepreneurial sector, a downsizing of the SOE sector will lead to not only more entrepreneurs but also better entrepreneurs on average.

We test the hypothesis with detailed firm registration and performance data maintained by the State Administration for Industry and Commerce of China, which covers the universe of all registered firms established in China since 1949. The database also contains basic demographic information of the legal representative and main initial shareholders, such as the age, the birthplace, and their shares in the company. We define an entrepreneur as the legal representative of a firm, and we exclude the self-employed individuals from the sample of entrepreneurs in our baseline empirical analysis. We focus on the over 5 million firms that were established during the period between 1993 and 2005, and track their performance until 2020.

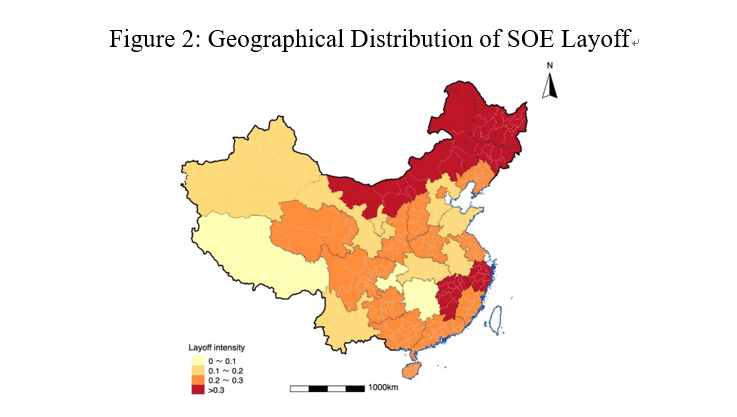

Our identification strategy relies on the heterogeneity across provinces in the realized intensity of SOE layoffs. We define the treatment intensity in a province as the percentage change in the number of SOE employees in 2001 relative to that in 1995. Figure 2 plots the geographical variations of the SOE layoff intensity, as measured by the percentage change in the number of SOE employees from 1995 to 2001 in the province. It shows significant regional variation in the layoff intensity. To identify the causal effect of SOE layoff on entrepreneurship, we rely on a difference-in-differences analysis that compares the entry and the performance of entrepreneurs from high layoff intensity provinces to those from low layoff intensity provinces, before and after the massive SOE downsizing in 1998. To address the concern that the realized layoff intensity in a province -- our measure of treatment intensity -- may be correlated with some unobserved provincial-level changes that affect the entrepreneurial market, we exploit the fact that provinces differ in the initial industry composition and different industries had different SOE presence before the SOE downsizing in 1998 to construct a Bartik shift-share instrument.

Notes: This figure plots the geographical distribution of the SOEs’ layoff intensity across the reform period (1995-2001), and it shows significant regional variation in the layoff intensity.

We show that the 1998 SOE downsizing boosted new firm creation as well as the entry of new entrepreneurs. Moreover, we find that the layoff-induced entrepreneurs outperformed other comparable entrepreneurs. Specifically, the average quality of entrepreneurs as measured by their firms’ performance metrics such as Return Of Equity (ROE), annual income, and profit, exhibited a larger increase following the 1998 SOE downsizing in the high-layoff intensity provinces compared to those in the low-layoff intensity provinces. This outperformance persists even after more than 10 years. Our finding is robust to a number of specifications and the use of the instrumental variable approach.

Recognizing the differences in the career choice problems faced by individuals who entered the labor market before the SOE reform started (prior to 1991), during the SOE reform (1992-1997), or after the SOE downsizing (after 1998), our model also predicts potential performance heterogeneity across entrepreneurs of different generations. Consistent with our theoretical prediction, we also find that the layoff-induced entrepreneurs who initially entered the labor market before 1991 (the older, pre-SOE reform cohort) perform worse than those who entered the labor market between 1992 and 1997 (the middle cohort), who in turn perform worse than those who entered the labor market after 1998 (the younger, post SOE downsizing cohort).

Of course, apart from the mechanism laid out above, there exist several potential alternative explanations that may rationalize our findings. For example, one alternative mechanism is that a province with more intensive SOE layoffs may lead to a more abundant local labor supply, which will decrease local labor costs and improve firm performance; a second potential mechanism is that a province with a more intensive layoffs releases more skilled labor into the local labor market, and it is the more skilled employees rather than the more able entrepreneurs that cause the new firms' better performance; a third potential mechanism is that provinces with higher SOE layoff intensities may be more pro-market during the SOE reform, which can encourage entrepreneurship and improve performance; and a fourth channel is that former SOE workers may have accumulated social capital such as networks that can contribute to their entrepreneurial performance after they leave the SOE sector. We carefully examine these channels and demonstrate that our results are not driven by these alternative mechanisms.

Concluding Remarks

SOEs, which provide more benefits to their workers, lead to a reluctance towards entrepreneurial endeavors among high-skilled individuals. The mechanism elucidated in this column bears significant implications for the influence of the state sector on the broader market economy. The allure of state-sector employment for high-skilled labor not only discourages private sector growth through labor allocation but also impedes the establishment of new productive private firms by the high-skilled, thereby stifling economic dynamism. When these previously highly skilled individuals are compelled to exit the SOEs, they reluctantly transform into successful entrepreneurs, catalyzing subsequent economic growth.

While we study the problem in the context of China in the era of SOE reform, we believe that the mechanism elucidated herein may extend to broader contexts that feature a strong state sector. The resurgence of SOEs in the Chinese economy from 2013 onward underscores the continued relevance of understanding the impact of SOEs on entrepreneurship for predicting future economic dynamism. Our findings may also shed light on cross-country comparisons of entrepreneurial quality. For example, countries and regions with a strong state or public sector that offer additional benefits, especially when social security is insufficient, may expect lower entrepreneurial qualities as a result.

(This is reposted from an article originally posted at VoxEU.)

References

Bai, C.-E., R. Jia, H. Li, and X. Wang (2021): “Entrepreneurial Reluctance: Talent and Firm Creation in China,” NBER Working Paper No. 28865.

Brandt, L., R. Dai, and X. Zhang (2023): “The Anatomy of SOE in China”. University of Toronto Working Paper.

Cheng, H., H. Li, and T. Li (2021): “Performance State-Owned Enterprises: New Evidence from China Employer- Employee Survey,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 69, 513–540.

Cull, R. and L. C. Xu (2003): “Who Gets Credit? Behavior Bureaucrats State Banks Allocating Credit Chinese State-Owned Enterprises,” Journal of Development Economics, 71, 533–559.

Decker, R., J. Haltiwanger, R. Jarmin, and J. Miranda (2014): “Role of Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28, 3–24.

Fang, H., J. Wu, R. Zhang, and L.-A. Zhou (2022): “Understanding the Resurgence of the SOEs in China: Evidence from the Real Estate Sector,” NBER Working Paper No. 29688

Fang, H., Li, M., Wu, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2023): “Reluctant Entrepreneurs: Evidence from China’s SOE Reform,” NBER Working Paper No. 31700.

Garnaut, R., L. Song, and C. Fang (2018): China’s 40 years of reform and development: 1978–2018, ANU Press.

Hacamo, I. and K. Kleiner (2022): “Forced Entrepreneurs,” Journal of Finance, 77, 49–83.

Haltiwanger, J., R. S. Jarmin, and J. Miranda (2013): “Who Creates Jobs? Small Versus Large Versus Young,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 347–361.

Harrison, A., M. Meyer, P. Wang, L. Zhao, and M. Zhao (2019): “Can Tiger Change Its Stripes? Reform Chinese State-Owned Enterprises Penumbra State,” NBER Working Paper No. 25475.

Hsieh, C.-T. and Z. M. Song (2015): “Grasp the Large, Let Go of the Small: The Transformation of the State Sector in China,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 295–346.

Min, H. (2011): “Former Officials Subsidies State-Owned Enterprises,” Journal of Economic Development, 36, 1.

Naughton, B. (1994): “What is Distinctive about China’s Economic Transition? State Enterprise Reform and Overall System Transformation,” Journal of Comparative Economics, 18, 470–490.

Queiró, F. (2022): “Entrepreneurial Human Capital and Firm Dynamics,” Review of Economic Studies, 89, 2061–2100.

Song, Z., K. Storesletten, and F. Zilibotti (2011): “Growing Like China,” American Economic Review, 101, 196–233.

Wang, Y. P., Y. Wang, and G. Bramley (2005): “Chinese Housing Reform State-Owned Enterprises Its Impacts Different Social Groups,” Urban Studies, 42, 1859–1878.

West, L. A. (1999): “Pension Reform in China: Preparing for the Future,” Journal of Development Studies, 35, 153–183.

Yu, H. (2014): “Ascendency State-Owned Enterprises China: Development, Controversy Problems,” Journal of Contemporary China, 23, 161–182.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email