Visible Hands: Professional Asset Managers’Expectations and the Stock Market in China

Mutual funds have become an important type of private institutional investor in Chinese security markets, with assets under management exceeding $3 trillion. We study how Chinese fund managers’ growth expectations affect their equity investment decisions, and in turn, the effects on stock prices. We identify a strong short-run causal effect of growth expectations on stock returns. We also find that fund investment helps bring prices in line with firms’ longer-run earnings prospects.

When informationally efficient, the prices of actively traded corporate securities can improve resource allocation in the business sector (Fama 1970; Chen, Goldstein, and Jiang 2007). Given the large amounts of potentially relevant data and the cost of processing and interpreting it, a related question is how information gets into prices. Empirical assessment of the who and how of price discovery generally requires data on the opinions, forecasts, investments, and/or ex post performance of a set of market participants or analysts. For example, some studies have focused on information production from professional investment analysis, such as company earnings forecasts or credit ratings, which typically come from third parties, rather than active investors (Bradshaw 2011; Kothari, So, and Verdi 2016; White 2013; Livingston, Poon, and Zhou 2018).

The starting point for our paper (Ammer et al. 2022) is Chinese mutual fund managers’ near-term macroeconomic growth forecasts, which are inferred by natural language processing of the qualitative discussion sections that were a required part of funds’ quarterly reports during the 2008–2020 sample period. An advantage of this approach is that these opinions come from the investors themselves, so they can be more directly linked to the investment decisions observed for the asset managers in the data set, to fund performance, and to the impact of managers’ growth expectations on the prices of the stocks that their funds hold or buy.

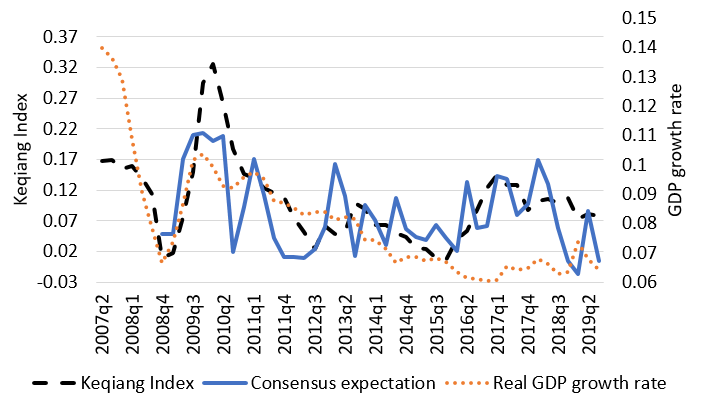

Figure 1: Consensus growth expectation, real GDP growth, and Keqiang Index

Note: Data are quarterly from 2007 Q2 to 2020 Q3. The Keqiang Index is a linear combination of the growth rate of electricity consumption (weight = 0.4), bank loans (weight = 0.35), and railway cargo volume (weight = 0.25). For ease of exposition, we display 0.2*consensus+0.1 on the left y-axis.

Each reading on a manager’s growth expectations is a value between -1 (a strongly pessimistic outlook) and +1 (strongly optimistic). The assignment of scores draws on a dictionary of relevant words and phrases, including keywords that identify the topic (such as nouns like “GDP growth” and “national income”), directional words (such as “increase” or “stagnant”), and scaling words indicating magnitude (such as “mildly” and “potentially”) or negation (e.g., “no” or “not”). Semantic clauses in a report can be scored if a keyword is accompanied by at least one directional word, and the score of a clause is computed as the product of its scorable parts. The score value of keywords is 1, directional words take on a value from {-1, -0.5, 0, 0.5, 1}, and scaling words from {-1, 0.5, 1}. The overall score for a fund report is the average of the scores we calculate from its clauses.

We confirm that the average (“consensus”) expectation across managers (Figure 1) has short-term predictive power for measures of macroeconomic growth, specifically GDP and the Keqiang Index, which provides validation both for the expectations measure and for fund managers’ competence in macroeconomic analysis. We also show that investment returns are higher for funds with managers who accurately forecast growth.

Managers’ growth expectations affect fund investment

We next assess the extent to which managers’ investment decisions reflect their growth expectations. We focus on actively managed equity and mixed (equity and bond) funds, for which managers would potentially be strategically adjusting their exposure to the broad economy through changes in equity positions. We find that optimistic growth expectations lead managers to choose more bullish portfolio allocations, shifting from cash or bonds to more equity investment and increasing the stock-market beta of their overall portfolios. In addition, within their stock portfolios, bullish managers reallocate toward firms in more cyclical industries and toward state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Earnings of SOEs are relatively procyclical, in part because cheap financing costs from an implicit government guarantee allows them to expand faster during booms. During downturns, cost-cutting is deterred by SOEs’ obligations to maintain both employment levels and their purchases of intermediate goods, as a required participatory contribution to countercyclical stabilization policy (Bai, Philippon, and Savov 2006; Song, Storesletten, and Zilibotti 2011).

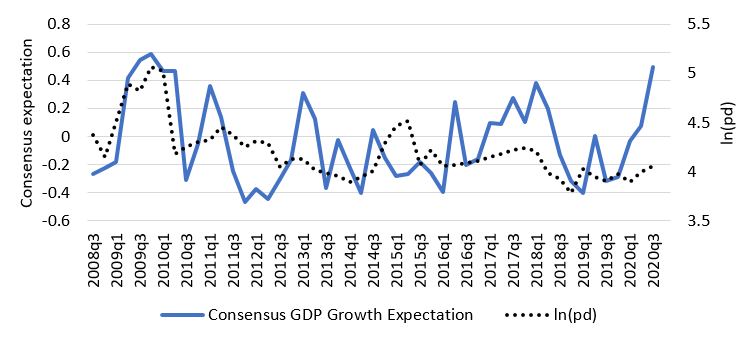

Figure 2: Comovement of the consensus growth expectation and the p-d ratio

Note: The blue solid curve is the consensus growth expectation, the black dashed curve is the log p-d ratio of the stock market.

Managers’ growth expectations affect stock prices

Fluctuations in managers’ growth expectations should affect asset prices through shifts in demand. At the aggregate level, we find that our measure of consensus expectation is positively correlated with the price-dividend ratio (p/d) for the market index (Figure 2). In regression analysis, we also confirm that the consensus growth expectation has explanatory power for p/d that goes beyond the information in lagged GDP growth.

The growth expectations of active fund managers can also have cross-sectional implications for stock prices. Turning to panel data, we show that the CAPM abnormal return on a stock is positively correlated with the contemporaneous growth expectations of active fund managers who held it at the end of the previous period. Furthermore, this effect is increasing in the fraction of outstanding company shares held by those managers. The estimated effect is also stronger, all else equal, when managers holding a stock have pessimistic expectations. Managers making bullish shifts because they have optimistic growth expectations might choose to diversify into new investments, trading decisions that need not put any upward pressure on the prices of the stocks that they already hold.

In contrast, the growth expectations of index funds’ managers have no effect on the prices of stocks in their portfolios, reflecting the passive investment mandate of index funds. For active fund managers, we infer their funds’ net purchases of each stock from changes in reported holdings. We confirm that this measure of trading is the main source of stock price adjustment, when measured at a point in time after managers have submitted their fund reports to the China Securities Regulatory Commission, but before these reports have been made public.

Short sale constraints can delay the adjustment of stock prices

One potential limitation on Chinese mutual fund managers’ participation in price discovery is that they are not permitted to take short positions. As has been shown theoretically, short-sale constraints generally induce incomplete pass-through of negative information (Hong and Stein 2003). An implication is that there should be a lagged response to negative information that manifests as a downward adjustment of stock prices in subsequent periods. Such a delay in price discovery should be strongest when market participants who are aware of negative information have smaller positions in the asset and thus less scope to sell. We find evidence that short sale constraints do delay price discovery of fund managers’ negative growth expectations. Specifically, below-average holdings in a stock by fund managers with pessimistic growth expectations leads to a lower abnormal return for that stock in the month after the report, all else being equal, as the market catches up to the negative information from the previous quarter.

Fund investment improves stock price informativeness about future company earnings

Given our evidence that China’s mutual fund managers and their growth expectations play a material role in price discovery, a natural extension is to assess more directly the extent to which funds’ investment choices contribute to equity valuations that reflect underlying fundamentals, which should depend mainly on companies’ prospects for future payoffs. We assess the extent to which stock price reflects a firm’s future earnings by estimating measures of “price informativeness” (Dávila and Parlatore 2018). Specifically, using stock prices and earnings in a 32-quarter rolling window, we compare the fit of two alternative regressions to capture the reduction in uncertainty about earnings growth that comes from observing the latest stock price.

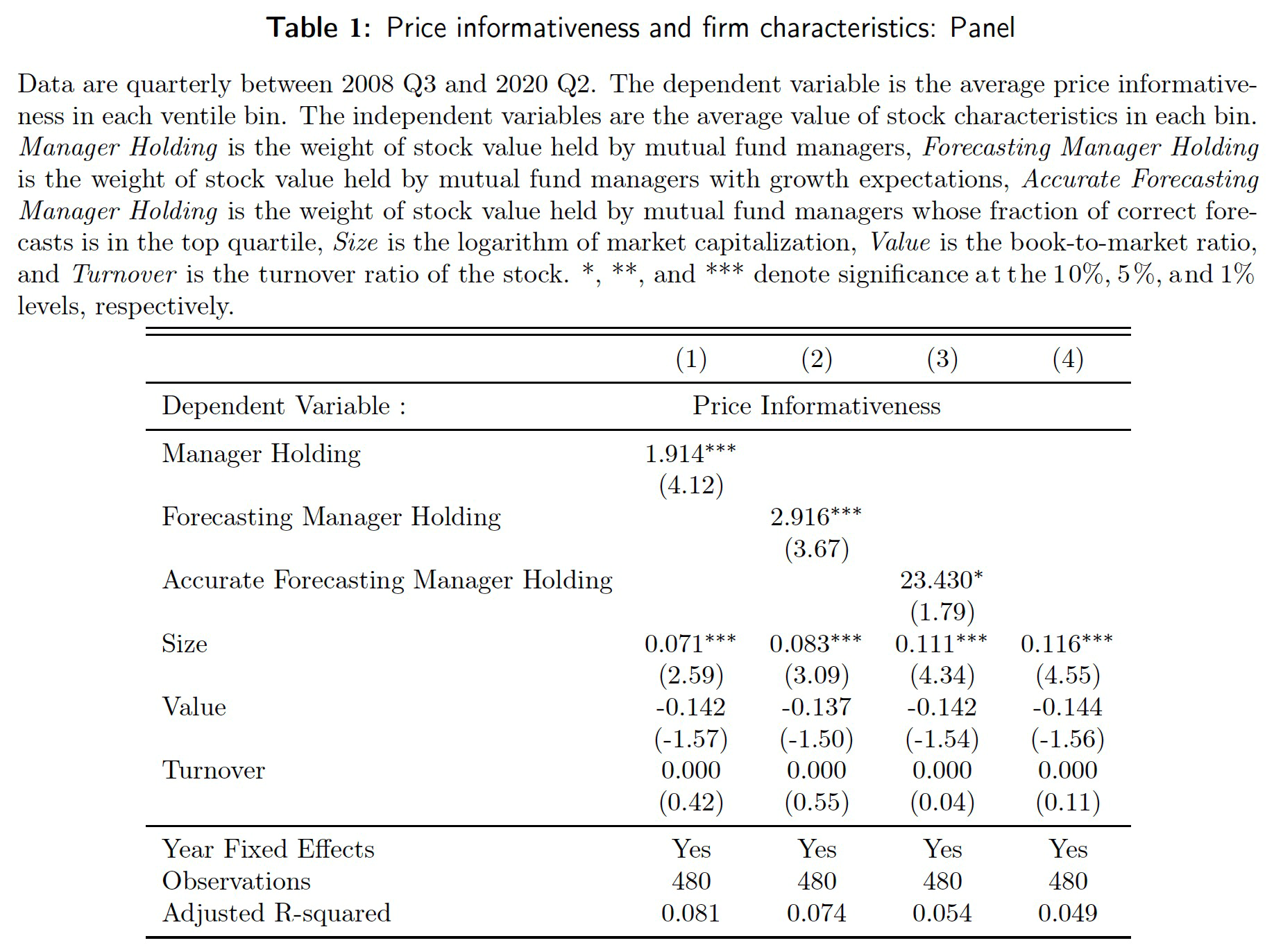

Previous papers have attributed an upward trend in price informativeness measures for the US and Chinese stock markets, respectively, to increasing application of rigorous investment analysis (Dávila and Parlatore 2018; Carpenter, Lu, and Whitelaw 2021). To gauge the contribution of Chinese mutual fund managers to price informativeness more explicitly than this, we first sort our sample stocks in each quarter by our price informative measure, dividing them into 20 equal-sized bins (Dávila and Parlatore 2018). Then, using bin-level averages in a panel setting, we regress price-informativeness against the fraction of the bin held by active mutual funds in our sample, also controling for size, book-to-market ratio, and turnover.

As shown in Table 1, price informativeness is increasing in mutual-fund holdings. Thus, fund managers also appear to contribute to a longer-horizon form of price discovery, helping to keep stock prices in line with an earnings-based measure of fundamental value, and potentially improving resource allocation across firms, as well as over time.

(John Ammer is a Senior Economic Project Manager in the International Finance Division at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC; John Rogers is a Professor of Economics at Fudan University; Gang Wang is an Associate Professor at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics; Yang Yu is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.)

References

Ammer, John, John H. Rogers, Gang Wang, and Yang Yu. 2022: “Visible Hands: Professional Asset Managers’ Expectations and the Stock Market in China.” International Finance Discussion Paper No. 1362. https://dx.doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2022.1362.

Bai, Jennie, Thomas Philippon, and Alexi Savov. 2016. “Have Financial Markets Become More Informative?” Journal of Financial Economics 122 (3): 625–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.08.005.

Bradshaw, Mark T. 2011. “Analysts’ Forecasts: What Do We Know after Decades of Work?” SSRN Working Paper No. 1880339. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1880339.

Carpenter, Jennifer N., Fangzhou Lu, and Robert F. Whitelaw. 2021. “The Real Value of China’s Stock Market.” Journal of Financial Economics 139 (3): 679–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2020.08.012.

Chen, Qi, Itay Goldstein, and Wei Jiang. 2007. “Price Informativeness and Investment Sensitivity to Stock Price.” Review of Financial Studies 20: 619–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhl024.

Dávila, Eduardo, and Cecilia Parlatore. 2018. “Identifying Price Informativeness.” NBER Working Paper No. 25210. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25210.

Fama, Eugene F. 1970. “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work.” Journal of Finance 25 (2): 383–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/2325486.

Hong, Harrison, and Jeremy C. Stein. 2003. “Differences of Opinion, Short-Sales Constraints, and Market Crashes.” Review of Financial Studies 16 (2): 487–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhg006.

Kothari, S. P., Eric So, and Rodrigo Verdi. 2016. “Analysts’ Forecasts and Asset Pricing: A Survey.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 8: 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-121415-032930.

Livingston, Miles, Winnie P. H. Poon, and Lei Zhou. 2018. “Are Chinese Credit Ratings Relevant? A Study of the Chinese Bond Market and Credit Rating Industry.” Journal of Banking and Finance 87: 216–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.09.020.

Song, Zheng, Kjetil Storesletten, and Fabrizio Zilibotti. 2011. “Growing like China.” American Economic Review 101 (1): 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.1.196.

White, Lawrence J. 2013. “Credit Rating Agencies: An Overview.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 5: 93–122. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-110112-120942.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email