Tournament-Style Political Competition and Local Protectionism: Theory and Evidence from China

Inter-jurisdictional competition in a regionally decentralized authoritarian regime distorts local politicians’ incentives in resource allocation among firms from their own city and a competing city. When local politicians are in more intensive political competition, they allocate fewer government procurement contracts to firms in the competing city, and local firms, especially local State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), internalize the politicians’ career concerns and invest less in the competing cities. These findings provide a political economy explanation for inefficient local protectionism when politicians engage in tournament-style political competition.

The seminal work of Xu (2011) argues that the institutional foundation underlying the successful Chinese economic reform can be referred to as regionally decentralized authoritarianism (RDA), which is characterized by a high centralization of political power and a high decentralization of administrative and economic power, with the incentives of the local politicians provided via promotion tournaments (Li and Zhou 2005). Under the RDA, local politicians are incentivized by inter-jurisdictional competition: to maximize their chances of career promotion, local government leaders compete against one another to spur total investment and boost the growth of the local economy (Yu, Zhou, and Zhu 2016; Xu 2011). The key difference between the RDA and democracy lies in the objective of the tournament participants. Unlike local politicians in a democratic regime who mainly respond to voters’ welfare, politicians in an autocratic regime respond mainly to upper-level government objectives. On the positive side, the central government can provide local leaders with strong career incentives, which are considered a key driver of China’s economic growth over the last thirty years (Li and Zhou 2005; Maskin, Qian, and Xu 2000; Blanchard and Shleifer 2001). On the negative side, because the economic development of each region is connected to other regions due to regional spillovers and externalities, tournament-style political competition may lead to socially inefficient resource allocation. In a recent working paper (Fang, Li, and Wu 2022), we ask the following questions. First, how does tournament-style political competition affect local politicians’ incentives in their economic policies regarding firms from competing cities? Second, to the extent that firms internalize local politicians’ career incentives, how would political competition influence their investment decisions and shape the country’s internal economic integration?

We first develop a model in which local politicians compete with one another for promotion in a tournament by selecting projects of varying returns. The model shows that under tournament-style political competition, the joint presence of regional spillover and political competition leads to local protectionism as manifested by resource allocations inefficiently biased against firms in the competing cities. The model also yields testable predictions regarding how the politicians’ career incentives and political network impact inter-jurisdictional resource allocations. We show that, for each pair of competing cities, the inter-city allocation of projects or resources are lower when the politicians are engaged in more fierce political competition, or when the politicians are closer to the end of their term, but are higher when politicians of the city pairs share political connections. Moreover, our model generates a sharp prediction that the effect of political competition on resource allocation should be affected in opposite directions by the local politicians’ connections and by how near they are to the end of their term.

In our empirical work, we first construct an empirical measure for the politicians’ “ability,” which we proxy by their ex ante (and exogenous) promotion probability, and use the ability differential between each city pair’s mayors to measure their competition intensity. Specifically, we estimate local officials’ likelihood of promotion by running a logit regression of the promotion dummy variable for each city-year, which takes value 1 if the city’s mayor was promoted to a higher-level position by the end of the year, on the set of personal characteristics such as age, gender, education level, tenure, factional ties, and the city characteristics including its economic performance, then use the estimated coefficients to predict the ex ante promotion likelihood for each mayor in each year, which we use to proxy as the politicians’ “ability” in that year. We then empirically test the model’s predictions regarding the relationship between city leaders’ competition and the inter-jurisdictional allocation of resources in the context of Chinese cities, focusing on city governments’ procurement allocations and firms’ equity investment across cities, both for the period of 2003 and 2019. Because government procurement is often used by local governments to support firms’ development, firms from another city whose local leader is in fierce competition with the procuring city will have, ceteris paribus, a lower probability of winning the procurement contract. We find that when mayors in a city pair are closer in their promotion probability, which indicates that they are engaged in more intense political competition, they allocate fewer government procurement contracts to firms in the competing city. Specifically, Table 1 shows that, after including an extensive set of controls, increasing the “ability” differential by one standard deviation (about 0.1)—i.e., weakening the intensity of competition—leads to a 3% (column 1) increase in the cross-city allocation of procurement contracts, and a 4% (column 2) increase in inter-city equity investment. Interestingly, we find that firms, especially local SOEs, internalize the local politicians’ career concerns and invest less in the competing cities (columns 3–5). Both findings suggest tournament-style competition leads to inefficient local protectionism and are robust to a set of alternative specifications.

Note: This table reports the results estimating the impact of political competition on the inter-city allocation of procurement contracts and firms’ investment. The data sample includes city pairs ij from the same province. The dependent variable for column (1) is the total number of procurement contracts (in logs) signed between firms in city i and government departments in city j in each year. The dependent variable for columns (2)-(5) is the equity investment flows (in logs) from city j to city i in each year, in total volume, and for firms with different ownership types, respectively. ai represents the promotion propensity score for city i’s mayor in each year, which serves as the proxy for his ability; |ai-aj| represents the ability differential between city i’s mayor and city j’s, which measures the intensity of political competition between the two mayors. Standard errors are estimated using cluster-bootstrap at the province-year level. ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

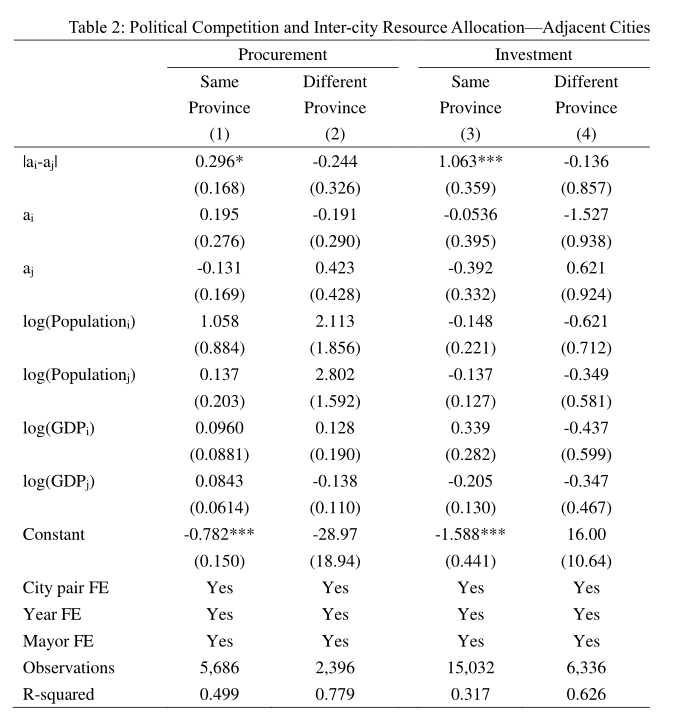

The theoretical model implies that it is the joint presence of regional spillover and the incentive for political competition that leads to resource allocations biased against firms in competing cities. To separately identify the role of the two forces in distorting resource allocation, we compare cities that are adjacent but not in the same province to the adjacent cities in the same province. Adjacent cities have stronger regional spillover regardless of whether they are in the same province, but only city leaders in the same province compete against one another for promotion. The comparison of the two enables us to identify the role of political competition. Thus, we run the main regression based on this adjacent cities sample. Table 2 suggests that increasing the “ability” differential by one standard deviation (about 0.1) leads to a 3% (column 1) increase in the cross-city allocation of procurement contracts and an increase in inter-city equity investment by 10% (column 3) if the two adjacent cities are in the same province; however, the effect turns negative and statistically insignificant for city pairs that cross province borders (columns 2 and 4).

Note: This table reports the results based on the adjacent city pairs sample. The dependent variable for columns (1)-(2) is the total number of procurement contracts (in logs) signed between firms in city i and government departments in city j in each year. The dependent variable for columns (3)-(4) is the equity investment flows (in logs) from city j to city i in each year. Columns (1) and (3) report the regression results for adjacent city pairs from the same province, and columns (2) and (4) report the regression results for adjacent city pairs from different provinces. All other variables are as defined in Table 1. Standard errors are estimated using cluster-bootstrap at the province-year level. ***, **, and * represent significance at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

Our empirical findings also corroborate the model predictions that political networks based on factional ties, working experience, or personal connections reduce the distortionary bias in resource allocation, and the distortion is more severe when local politicians approach the end of their terms and thus have more imminent career concerns. Our analysis points to the inefficient inter-jurisdictional resource allocation in the form of local protectionism as an unintended consequence of tournament-style political competition.

Our theoretical and empirical findings altogether accentuate the potential downside of tournament-style political competition. We underline a key mechanism through which political competition affects local policies toward firms in other regions: local officials are disincentivized to support the growth of firms from a competitor’s region because they are assessed by the upper-level government on their relative economic performance in a promotion tournament. In the absence of regional spillover or promotion incentive, each city should treat firms from everywhere equally and conduct business with those of the highest quality. However, doing business with firms from other regions generates short-run economic benefits to that region, which in turn increases the promotion probability of the competing politician. As such, career-concerned local leaders may distort resource allocation against firms from the competing city. This results in local protectionism, where local firms are favorably treated at the cost of efficiency. Further, firms may seek protection from the local government due to the lack of adequate formal market-supporting institutions and take into account the local officials’ preferences in their investment decisions. As a result, they tend to invest less in cities whose local leaders are in more intense political competition against leaders of their home city, which can again lead to social inefficiency.

References

Blanchard, Olivier, and Andrei Shleifer. 2001. “Federalism with and without Political Centralization: China versus Russia.” IMF Staff Papers 48 (1): 171–79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4621694.

Fang, Hanming, Ming Li, and Zenan Wu. 2022. “Tournament-Style Political Competition and Local Protectionism: Theory and Evidence from China.” NBER Working Paper No. 30780. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30780.

Li, Hongbin, and Li-An Zhou. 2005. “Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (9–10): 1743–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009.

Maskin, Eric, Yingyi Qian, and Chenggang Xu. 2000. “Incentives, Information, and Organizational Form.” Review of Economic Studies 67 (2): 359–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-937X.00135.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011. “The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development.” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4): 1076–1151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.4.1076.

Yu, Jihai, Li-An Zhou, and Guozhong Zhu. 2016. “Strategic Interaction in Political Competition: Evidence from Spatial Effects Across Chinese Cities.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 57: 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2015.12.003.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email