QR Code-Based Mobile Payments and Financial Inclusion

By means of a unique dataset of around half a million Chinese firms, we investigate the link between the use of a QR code-based mobile payment system and financial inclusion. We find that the use of digital payments allows firms to access credit provided by the big tech company operating the payment platform. The transaction data generated via QR code and the creation of a financial footprint in the credit registry also produce spillover effects on access to bank credit. Finally, there are positive effects of access to big tech credit on firms’ sales, including during the COVID-19 shock..

T he presence of information asymmetries between small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and credit intermediaries is a serious problem that may reduce financing of good investment opportunities and the development of promising entrepreneurs’ projects (Petersen and Rajan 1994, Berger and Udell 2006). Possible solutions to mitigate this problem for SMEs are posting collateral or relying on credit history (solutions often referred to as transaction-based lending) or building close and long-term relationships with specific lenders (relationship lending). Artificial intelligence, however, has provided a new solution, allowing large technology firms (big techs) to use credit-scoring techniques—based on a vast amount of data and machine learning techniques—to better capture the riskiness of clients operating in their business platforms (BIS 2019, Cornelli et al. 2020).

It is widely known that big techs operate e-commerce platforms that enable direct interaction among a large number of online merchants (Frost et al. 2019, Hau et al. 2021). Furthermore, in more recent years, the increasing use of quick response (QR) payment has allowed big techs to get information not only on e-commerce platforms, but also offline transactions, for example, at shops or restaurants (Gambacorta et al. 2022). Small businesses, even those not equipped with point-of-sale (POS) machines, are now able to collect payments through a simple QR code. Such innovation lowers the cost of small business to access electronic payments, therefore reducing the need for cash. Big techs have already become substantial players in digital payments in several advanced and emerging market economies (FSB 2019a, 2019b). They account for 94% of mobile payments in China (Carstens et al. 2021).

In addition to more effective payment services, QR code-based mobile payments can have also positive effects for financial inclusion. The use of QR code payments generates a vast amount of data that big techs can use to better assess the risk profile of customers and provide them with credit services. It is therefore interesting to evaluate whether (i) the use of QR code payments gives merchants who use QR code payments access to big tech credit, (ii) whether access to and use of big tech credit gives firms access to more traditional bank credit, and (iii) whether there are real effects of the use of QR code payments and the subsequent provision of credit on firms’ business volume.

We try to answer these three questions using a unique dataset that compares the characteristics of loans provided by MYbank, one of the brands under Ant Group (an important big tech company in China) with those of loans supplied by traditional financial institutions (Beck et al. 2022). In particular, we study a random sample of around 500,000 Chinese firms that used QR code-based mobile payments from January 2017 to July 2020. The analysis of this period also allows us to conduct a test during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, we have access to detailed information on credit supplied by MYbank and traditional banks as well as on firms’ characteristics, such as their transaction volumes and network score (a measure of firms’ centrality in the big tech ecosystem).

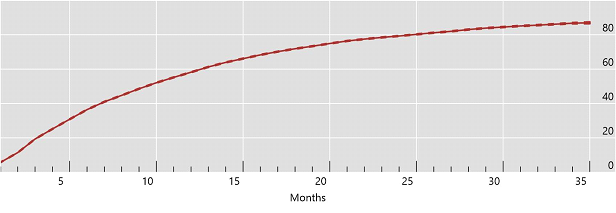

With respect to the first question, we find that the collection of data on digital payments (e.g., transaction volume, location, importance in payment network) allows firms to access credit provided by the same big tech company operating the platform. Figure 1 shows a rapid increase in the likelihood of gaining access to big tech credit the longer the firm uses QR codes in payments. The horizontal axis shows the amount of time elapsed between when a firm starts using QR codes for payment purposes and when it receives the offer of a credit line from MYbank, while the vertical axis reports the probability of having access to big tech credit. One year after starting to use QR code payments, the probability to have access to a big tech credit line reaches almost 60%. This probability increases to 80% after two years.

Figure 1. Does the Use of QR Codes in Payment Give Firms Access to Big Tech Credit?

In percent

Dashed lines indicate 5th/95th

percentiles. The x-axis reports the QR code duration, that is, the number of

months after the firm started to use the QR code payment system. The y-axis

reports the probability of a firm of having access to big tech credit.

Source: Beck et al (2022).

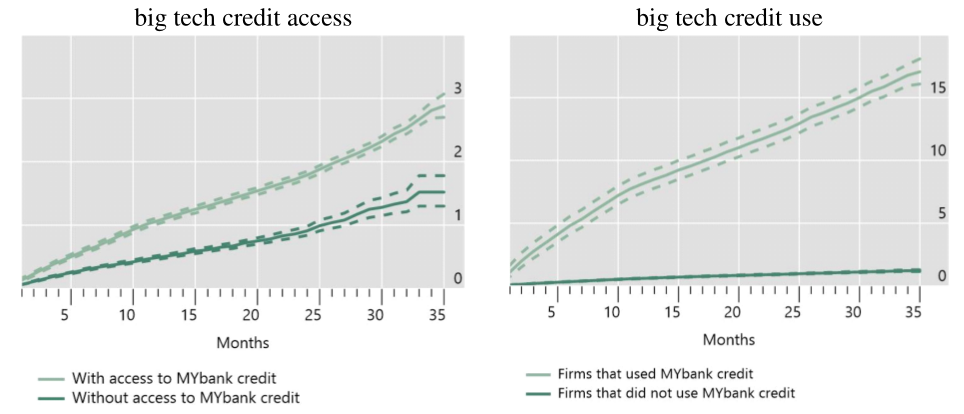

Answering the second question, we find that transaction data generated via QR code payments generate spillover effects on the use of bank credit. However, Figure 2 shows that there are substantial differences between the effects of simple access to big tech credit and the actual use of it. Controlling for demand effects, when firms have only access to big tech credit (but do not use it), the spillover effects on bank credit are quite limited. This is because simple access to big tech credit is not visible to banks in the credit registry. After three years of use of the QR code, the probability of using bank credit for firms with access to MYbank credit is only 3% (Figure 2, left). By contrast, actual use of a big tech credit line significantly increases the probability of having access to bank credit, likely because in this case a financial footprint is created in the credit register: three years after starting to use the QR codes, the probability of using a bank credit line is around 17%. This means that the inclusion of big tech credit exposures in the credit registry acts as a signaling device and allows SMEs to be better identified and screened by banks.

Figure 2. Spillover Effect from Big Tech Credit to Bank Credit

In percent

Dashed lines indicate 5th/95th

percentiles. The x-axis reports the QR code duration, the number of months

after the firm started to use the QR code payment system. The y-axis reports

the probability for a firm of using bank credit.

Source: Beck et al (2022).

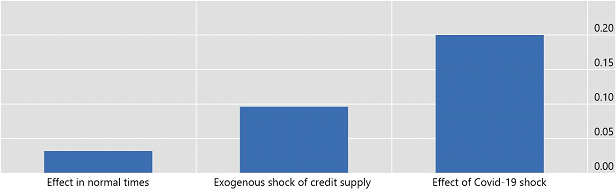

To answer the third question, we use three different tests to verify whether access to big tech credit produces real effects for firms’ activity. The first test analyses the pre-COVID-19 period of 2017–2019, while the second test considers only the exogenous shock generated by the introduction of the big tech loan product in August 2017. The third test compares the pre-pandemic period to the pandemic period, considering firms with and without access to big tech credit. Figure 3 reports the results of the three different tests. In the pre-pandemic period, transaction volume increased around 3.5% more (after three months) for firms that had access to big tech credit (treated group) than those with similar characteristics that did not have access (control group). When we limit the analysis to around the launch of the loan product, the effects are more sizable: transaction volume increases by 9.6% more (after three months) for those firms that received the initial offer of big tech loans than the others. Finally, the third test shows that the real effect during the COVID-19 pandemic is significantly larger than that in the pre-pandemic period: transaction volume growth is 20% higher for firms with access to big tech credit than those that were financially excluded.

Figure 3. Real Effects of Access to MYbank Credit

Increase in transaction volume (log)

Note: The first test (left histogram) evaluates the effects (after three months) of the provision of big tech credit on firms’ transaction volumes over the period 2017–2019. The analysis is based on a propensity score matching combined with a difference-in-differences type of analysis. The second test (middle histogram) uses a similar approach but focuses only on the initial offering of big tech loans. Ant Group introduced the possibility of MYbank credit products to QR code merchants at the end of June 2017 and started to supply loans in August 2017. The third test (right histogram) considers the specific effects during the pandemic.

Source: Beck et al (2022).

In summary, the use of apps for mobile payments, through so-called QR codes, simplifies the collection of payments for firms at a reduced cost. This can help firms increase transaction volumes as well as disclose characteristics of transactions via payment data. Big techs can process these data—together with other non-traditional information collected on social media, search engines and e-commerce platforms—to generate a credit score. In this way, firms that are typically unbanked and lack financial statements can have access to small loans that are not collateralized and typically used to adjust their liquidity needs. The use of QR codes thus has positive effects on financial inclusion that go well beyond the efficient processing of payments. Our analysis notably shows that the use of digital payments allows firms to access credit services offered by big techs. Moreover, the use of big tech financial services and the transaction data generated via QR codes produce spillover effects on access to bank credit. Specifically, the inclusion of big tech credit exposures in the credit registry acts as a signaling device that gives SMEs access to more traditional banking services. Finally, access to big tech credit has also positive effects on firms’ volume of business. These effects are significantly larger during the COVID-19 period, when credit lines were used to insulate the effects of an unexpected shock.

References

Bank for International Settlements. 2019. “Big Tech in Finance: Opportunities and Risks.” BIS Annual Economic Report. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2019e3.pdf.

Beck, Thorsten, Leonardo Gambacorta, Yiping Huang, Zhenhua Li, and Han Qiu. 2022. “Big Techs, QR Code Payments, and Financial Inclusion.” BIS Working Paper No. 1011. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1011.htm.

Berger, Allen N., and Gregory F. Udell. 2006. “A More Complete Conceptual Framework for SME Finance.” Journal of Banking and Finance 30 (11): 2945–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.008.

Carstens, Agustín, Stijn Claessens, Fernando Restoy and Hyun Song Shin. 2021. “Regulating big techs in finance”, BIS Bulletin No. 45. https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull45.htm

Cornelli, Giulio, Jon Frost, Leonardo Gambacorta, Raghavendra Rau, Robert Wardrop, and Tania Ziegler. 2020. “Fintech and Big Tech Credit: A New Database.” BIS Working Paper No. 887. https://www.bis.org/publ/work887.pdf.

Financial Stability Board. 2019a. “FinTech and Market Structure in Financial Services: Market Developments and Potential Financial Stability Implications.”https://www.fsb.org/2019/02/fintech-and-market-structure-in-financial-services-market-developments-and-potential-financial-stability-implications/.

Financial Stability Board. 2019b. “BigTech in Finance: Market Developments and Potential Financial Stability Implications.” https://www.fsb.org/2019/12/bigtech-in-finance-market-developments-and-potential-financial-stability-implications/.

Frost, Jon, Leonardo Gambacorta, Yi Huang, Hyun Song Shin, and Pablo Zbinden. 2019. “BigTech and the Changing Structure of Financial Intermediation.” Economic Policy 34 (100): 761–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiaa003.

Gambacorta, Leonardo, Yiping Huang, Zhenhua Li, Han Qiu, and Shu Chen. 2022. “Data Versus Collateral.” Review of Finance, rfac022. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfac022.

Hau Harald, Yi Huang, Hongzhe Shan, Zixia Sheng. 2021. “FinTech credit and entrepreneurial growth.” Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3899863.

Petersen, Mitchell A., and Raghuram G. Rajan. 1994. “The Benefits of Lending Relationships: Evidence from Small Business Data.” Journal of Finance 1: 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1994.tb04418.x

Tang, Huan. 2019. “Peer-to-Peer Lenders Versus Banks: Substitutes or Complements?” Review of Financial Studies 32 (5): 1900–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhy137.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email