China’s New Goal for Income Distribution: What Does it Mean and are There Tradeoffs?

China’s political leadership recently committed to expanding the proportion of middle-income groups to create a less polarised, and more ‘olive-shaped’, distribution of wealth. This column considers the potential trade-offs between reducing income polarisation and other goals, including poverty reduction. An obvious concern is how the process of economic growth impacts the extent of polarisation, but the country’s historical record does not point to any serious trade-offs going forward, including with economic growth, poverty reduction, and overall social welfare. However, potential trade-offs would need to be considered further in the context of specific policy efforts, such as expanding social service coverage in rural areas.

President Xi was clearly not saying that this is the only policy goal for China, even among those goals related to the distribution of income. (Xi has often emphasized the goal of ending poverty.) So, the question naturally arises as to what trade-offs might exist against other goals. That is a difficult question. Trade-offs can be hard to identify ex-post in observable data, which also reflect past shocks and policy choices (given the trade-offs faced at the time). Nonetheless, it is of interest to see what the historical experience suggests about trade-offs with regard to this new goal. This requires that we can quantify attainments of the multiple distributional goals, including defining and measuring the idea of “fleshing out the olive” (Economist 2021).

China's well-documented success in reducing absolute poverty came (of course) with a rising share of the population living above the official poverty lines (Chen and Ravallion 2021). Many of those who escaped absolute poverty joined China’s “middle-class.” Naturally, what this means depends on the setting. The prevailing definition of a “middle-income group” can be expected to change over time with rising living standards; what was considered a “middle” income in the China of the 1980s is clearly not the same as today. “Fleshing out the olive” can be interpreted as reducing the spread of incomes relative to the current median, which arguably provides a more relevant reference point than a fixed absolute level of real income.

This perspective suggests that the concept of “polarization” found in economics is relevant to monitoring China’s performance in “fleshing out the olive,” and identifying potential trade-offs against other goals. And there is a measure available in the literature, namely the Foster-Wolfson (FW) polarization index (Foster and Wolfson 2010). The greater the spread of incomes relative to the median (in either direction) the higher the FW index.What trade-offs might be found between this concept of polarization and other goals for the distribution of income? And what does the time-series evidence suggest?

Trade-offs?

Our new paper, “Fleshing out the Olive?,” points to some theoretical arguments about potential trade-offs between reducing income polarization—interpreted as the spread of incomes relative to the median—and other valued goals, including poverty reduction. Some policies that are good for fighting poverty and inequality could well be polarizing. Policy makers need to be aware of these potential trade-offs. How much they matter in practice is an open question.

An obvious concern is how the process of economic growth impacts the extent of polarization. One can make theoretical arguments either way. A growth process that only raises the incomes (relative to the median) of the upper half of the distribution will clearly be polarizing, while a growth process that only raises the incomes of the poorest half (relative to the median) will be de-polarizing. On the other hand, a distribution-neutral growth process—whereby all income levels increase by the same proportion—will leave the polarization index unchanged. Yet such a growth process can be effective in reducing absolute and weakly-relative poverty, as well as enriching the middle class in absolute terms (Ravallion 2016).

While it is not something that has attracted much attention in the literature, one might expect that the process of economic development through structural transformation in a country such as China can have a de-polarizing effect, as the poorest move closer to the middle. Nor is this an aspect of the potential distributional changes with development that is likely to be captured well by the standard inequality indices. Potentially de-polarizing gains among the poorer half may, however, come hand-in-hand with polarizing gains among the (primarily urban) upper half, comprising an elite of skilled workers and those who own the capital stock and/or rental properties.

Counter arguments to the idea that a less polarized distribution will yield lower economic growth can also be drawn from the literature on growth economics. One strand of that literature has argued that a larger middle-class share (by various measures) can promote economic growth and poverty reduction. (Our paper cites various papers on this topic.) We need not find any aggregate trade-off over time.

Also relevant in the context of China is the evolution of the large disparities found between mean incomes in urban and rural areas. This reflects long-standing inequalities in social policies (health, education and social protection) as well as impediments to internal migration, notably through the hukou registration system, and administrative land allocation processes. (Our paper provides references to the literature on these points.) Given the large mean income gaps between China’s urban and rural areas, the degree of urban-rural sectoral fractionalization—the extent to which people live in different sectors—can also matter to both income inequality and polarization.

These observations suggest that a focus on polarization begs some new policy questions that will need further thought. A prominent example in contemporary China is the Central Government’s goal of eliminating the hukou registration system—the internal “passport” system in China that restricts the access of rural migrants to urban services and markets. While ongoing reforms to the hukou system would undoubtedly help reduce poverty, the impact on polarization is unclear, given that the bulk of both the personal benefits and the costs of relaxing hukou restrictions may well fall on the lower side of the median, suggesting that these reforms could be polarizing. The potential for such polarizing effects of relaxing hukou restrictions would need to be balanced against other considerations, including poverty reduction.

What does the time-series evidence suggest?

In addition to arguing that the Foster-Wolfson index is a close match to the spirit of the idea of “fleshing out the olive”—and so provides a valuable tool for monitoring progress in attaining that goal—our new paper looks for signs of trade-offs in the aggregate time series data for China since soon after Deng Xiaoping’s growth-promoting reforms, launched in the late 1970s. To make our estimates back to the early 1980’s, we have no choice but to rely on published tabulations of the distribution of income in China, as produced by the National Bureau of Statistics. (The micro data from NBS’s surveys are not publicly available.) From the data available, we estimate parameterized Lorenz curves, separately for urban and rural areas. We then aggregate these into a national Lorenz curve, allowing for the higher cost-of-living in urban China, also factoring in the differences in the rates of price inflation between urban and rural areas. (Our methods are described more full in Ravallion and Chen 2021.)

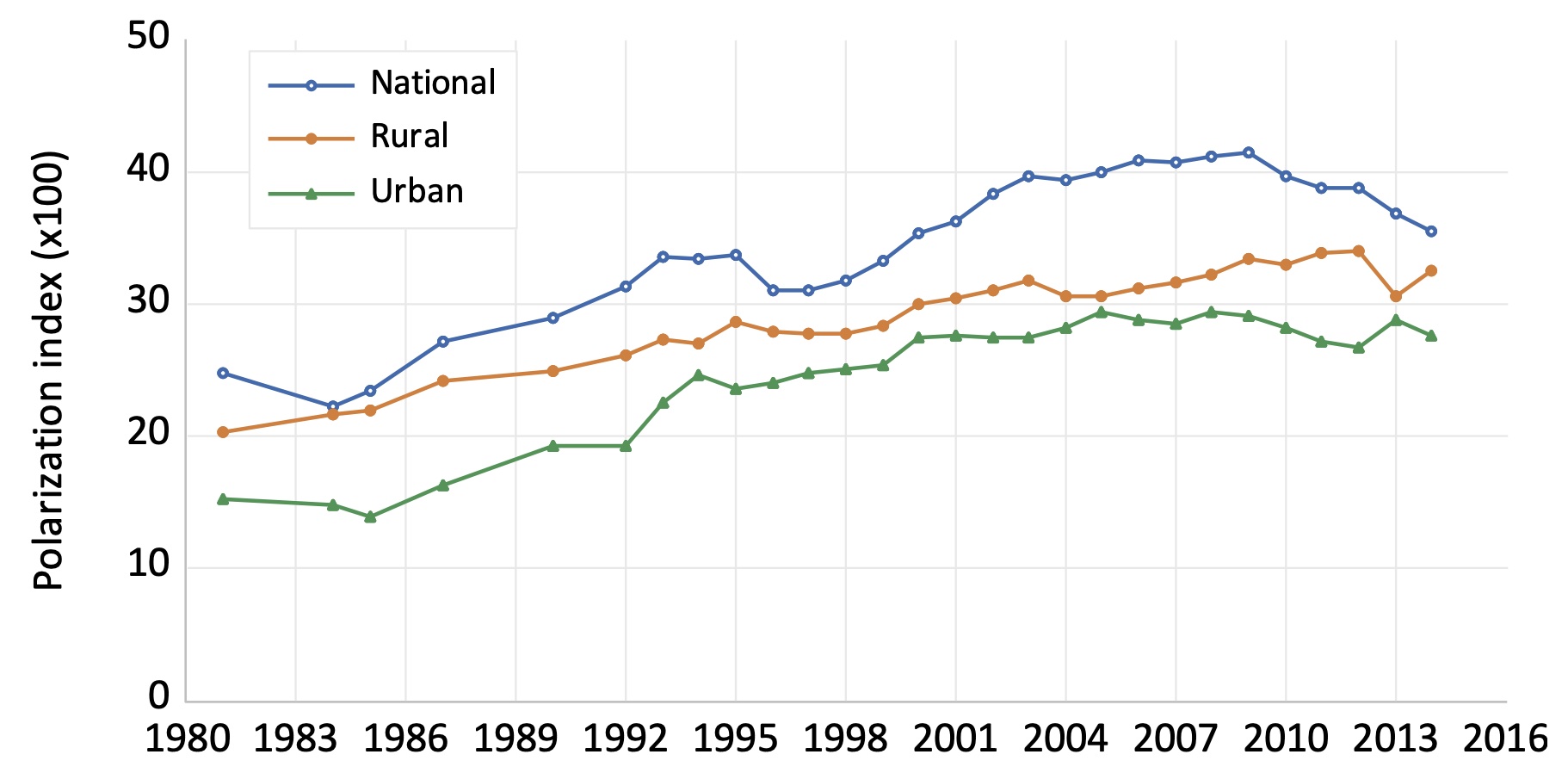

Figure 1 summarizes our estimates of the FW polarization index over time. We see an overall upward drift in the extent of polarization nationally, though with two distinct turning points, a brief one in the mid-1990s, and another starting in 2009. The TPs are less pronounced within each of urban and rural areas, suggesting the presence of some strong between-sector effects.

Figure 1 Income polarization indices for China

Our paper finds rather little evidence in the time-series data of any negative co-movement between polarization (on the one hand) and economic growth or reducing poverty and inequality (on the other). We find that polarization rose with rising average incomes up to 2009, but this appears to be spurious, reflecting common time trends. Periods of higher poverty reduction or higher economic growth did not typically see more rapid polarization. And we find strong co-movement between the Gini index and the Foster-Wolfson polarization index. Nor do we find that periods of a more rapid rise in the urbanization of the poorer half of the population (who started off almost only in rural areas) tended to be more polarizing.

To the extent that reducing polarization is a new policy goal for China, the historical record does not point to any serious trade-offs with past goals going forward, including with economic growth, poverty reduction and overall social welfare. The recent reversal in the generally upward path for polarization in China has been driven almost entirely by attenuated median-normalized incomes among the upper half.

Of special relevance to thinking about the future policy options in reducing polarization is our finding that the rise and fall in China’s national polarization index in Figure 1 is largely accountable to the evolution of the gap between urban and rural mean incomes. Here too, the historical record provides little support for the idea that reducing urban-rural disparities would be polarizing—indeed, the data we have assembled suggest the opposite. However, potential trade-offs would need to be considered further in the context of specific policy efforts, such as in expanding social service coverage in rural areas, also taking account of how those efforts are financed.

(This article was first published on VoxEU: https://voxeu.org/article/china-s-new-goal-income-distribution-insights-survey-data)

ReferencesChen, Shaohua, and Martin Ravallion, 2021, “Reconciling the Conflicting Narratives on Poverty in China,” Journal of Development Economics 153 (November): in progress.

Economist, The, 2021, “Fleshing Out the Olive,” The Economist Magazine August 28.

Foster, James, and Michael Wolfson, 2010, “Polarization and the Decline of the Middle Class: Canada and the U.S.,” Journal of Economic Inequality 8: 247–73.

Ravallion, Martin, 2016, The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement, and Policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ravallion, Martin, and Shaohua Chen, 2021, “Fleshing Out the Olive? On Income Polarization in China,” NBER Working Paper 29383.

Xinhua News Agency, 2021, “Xi Jinping Report Collection,” Xinhua News Agency, Beijing, August 17th.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email