The Impact of FDI on Domestic Firm Innovation: Evidence from Foreign Investment Deregulation in China

This paper studies the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on domestic firms’ innovation in China. Using firm level patent application records that cover all manufacturing firms with annual sales above 5M Yuan from 1998 to 2007, our results show that both the quantity and quality of domestic firms’ innovation benefit from FDI. In addition to the traditional spillover effect from FDI in the same industry, the paper emphasizes the importance of knowledge spillover: FDI in similar technology domains spurs domestic firms’ innovation much more than FDI in the same industry. The paper also shows that knowledge spillover from FDI in similar technology domains is not driven by input-out linkages. And the spillover effect is stronger in cities with higher human capital stock and firms with higher absorptive capacity.

Innovation is an essential driver of economic growth and policy makers make huge efforts to encourage innovation, such as human capital investment and support for research and development (R&D). But developing countries find it hard to close the technology gap with rich countries on their own. They often seek to open their markets and attract foreign direct investment (FDI) in the belief that FDI can spur domestic innovation and industry upgrading. However, we still have no clear evidence on whether FDI promotes domestic firms’ innovation or not.

The relationship between FDI and domestic firms’ innovation is not clear in theory. On the one hand, foreign firms can disseminate cutting-edge technology as well as hire and train local workers, generating positive effects on domestic firms’ innovation. The presence of FDI in the same industry could lower the cost of domestic firms’ innovation through multiple channels, including demonstration effect, supplier sharing, and labor mobility (Javorcik and Spatareanu 2009; Alfaro and Rodríguez-Clare 2004; Alfaro-Ureña et al. 2019; Bai et al. 2020). Besides the traditional horizontal FDI spillover effect, researchers have recently realized the importance of spillover within similar technology domains, because knowledge can be transferred to firms that share similar industry know-how and talent input. Fons-Rosen et al. (2017) find that FDI can boost domestic firms’ productivity and innovation if foreign firms enter sectors that are technologically close to domestic firms. FDI could also induce learning and upgrading in upstream and downstream firms through input-output linkages (Javorcik 2004, 2008). On the other hand, FDI could hurt domestic firms’ performance through the competition effect, because heightened competition can discourage domestic firms’ innovation (Aghion et al. 2005). If the technology gap between home and host countries is too large or domestic firms lack sufficient absorptive capacity, they would not be able to assimilate the knowledge brought by FDI (Zhang et al. 2010). Ultimately, the impact of FDI on domestic firms’ innovation remains an underexplored topic.

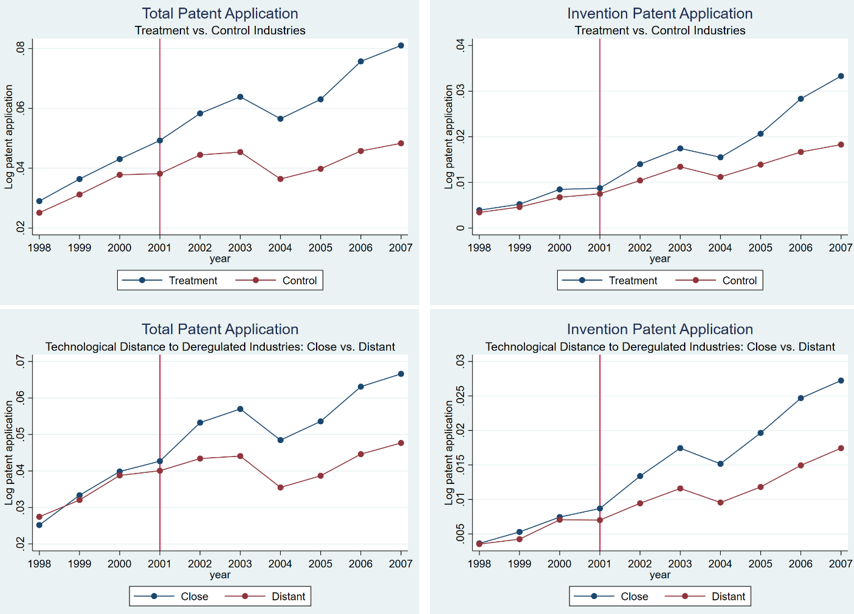

In a recent paper, we provide causal evidence on whether domestic firms become more innovative after exposure to FDI. We focus on two main measures of FDI presence: the traditional horizontal FDI (measured by the share of FDI in the same industry) and technologically close FDI (measured by FDI from industries that share similar technological domains) (see Note 1). We explore China’s FDI deregulation in 2002 upon joining the WTO, which exogenously increased the share of FDI in deregulated industries. The deregulation in 2002 allows us to use a difference-in-difference (DID) estimation strategy to establish the causal impact of FDI. China liberalized 112 of its 425 four-digit manufacturing industries for FDI; these industries indeed experienced higher growth in FDI inflows than control industries after 2002. To examine whether our DID design is valid, we first show graphical evidence that before 2001 patent applications in treatment (Close) and control (Distant) groups follow similar patterns (Figure 1). In the case of horizontal FDI (the upper panel), the treatment group is firms in deregulated industries and the control group is firms in other industries. In the case of technologically close FDI (the bottom panel), treated firms (Close) are those closer to deregulated industries in terms of the technology distance and control firms (Distant) are the distant ones. Treatment (Close) and control (Distant) groups show parallel trends before treatment and the trends only began to diverge after 2001, suggesting that the two groups are comparable.

Figure 1. Domestic firms’ patent application trends

Note: Figure 1 plots the trend in domestic firms’ total and invention patent application by group over time. The upper panel shows how domestic firms in industries that opened up for FDI in 2002 compare with domestic firms in other industries in patent applications. The bottom panel compares patent application patterns in domestic firms that have above median technological closeness (Close) to deregulated industries with those that have below median technological closeness (Distant).

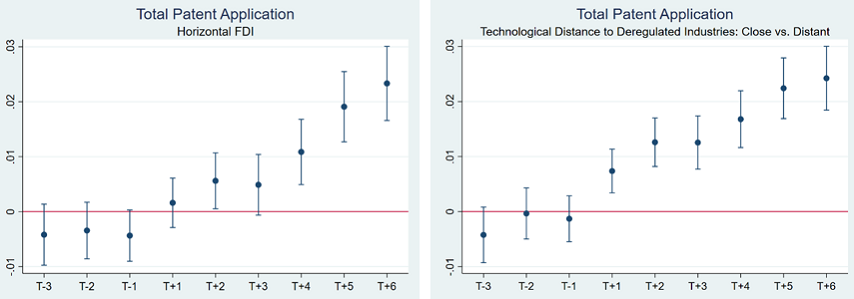

Our event study confirms the positive impact of horizontal and technologically close FDI on domestic firms’ innovation by showing that the estimated difference in patent applications before 2001 is tiny and statistically insignificant (Figure 2). Domestic firms in the treatment group become more innovative right after the reform. The effect is larger and more significant for domestic firms in industries that are technologically close to deregulated industries.

Figure 2. Event study estimation: FDI liberalization and domestic firms’ patent application

Note: The left panel of Figure 2 displays the estimated coefficients on total patent application difference between industries that were opened up for FDI in 2002 and those that did not (control group) and the 95% confidence interval. The right panel displays the estimated coefficients on total patent application difference between industries that have above median IV_techclosei2002 (Close) and those that are below median (Distant) and the 95% confidence interval. Above median IV_techclosei2002 indicates the industry is more technologically close to deregulated industries.

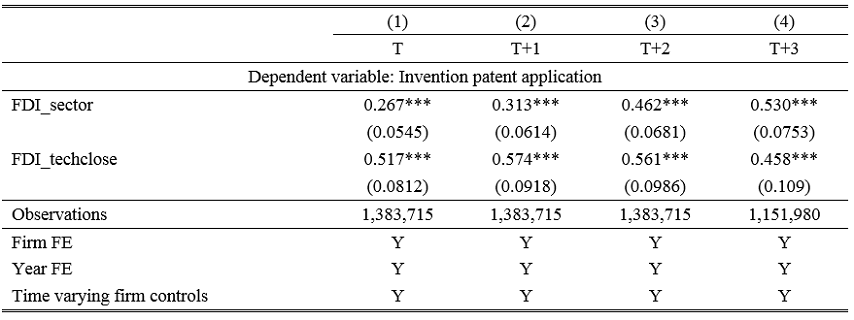

Using an IV-DID approach, our baseline regression results indicate that both horizontal FDI and technologically close FDI promote domestic firms’ innovation (Table 1). We focus on invention patent application because it is the most novel type of innovation. A one percentage point increase in foreign equity share in the same industry results in a 0.27 % increase in domestic firms’ invention patent application in the same year. The effect increases to 0.53 % after three years. A one percentage point increase in foreign equity share in technologically close industries can lead to a 0.52 % increase in domestic firms’ invention patent application in the same year of exposure. The coefficients on technologically close FDI also persists even three years after exposure. The above results indicate that knowledge spillover from FDI is much larger in technologically close industries than in the same industry.

Table 1. IV model: Invention patent application

Note: Table 1 reports dynamic effects of exposure to horizontal and technologically close FDI on domestic firms’ invention patent application based on IV model. The dependent variable is domestic firms’ invention patent application. Column (1) reports the effect in the year of exposure, while column (2)-(4) reports lagged effect after 1 to 3 years of exposure. Time varying firm controls include firm sales, capital-labor ratio, export status and SOE dummy. Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

We also tested how the effect varies by patent type, patent quality, and conducted various placebo tests and robustness checks to rule out the effects of vertical FDI and trade shocks. Exposure to FDI seems to have limited effect on domestic firms’ design patent application. Both horizontal and technologically close FDI have strong, positive, and increasing effect on domestic firms’ utility model patent application, but the effect from horizontal FDI is larger. This is intuitive as it is easier to conduct minor innovation through imitating the technology of foreign competitors. Using patent grant and citation as a measure of patent quality, we confirm that horizontal and technologically close FDI significantly improve domestic firms’ patent quality.

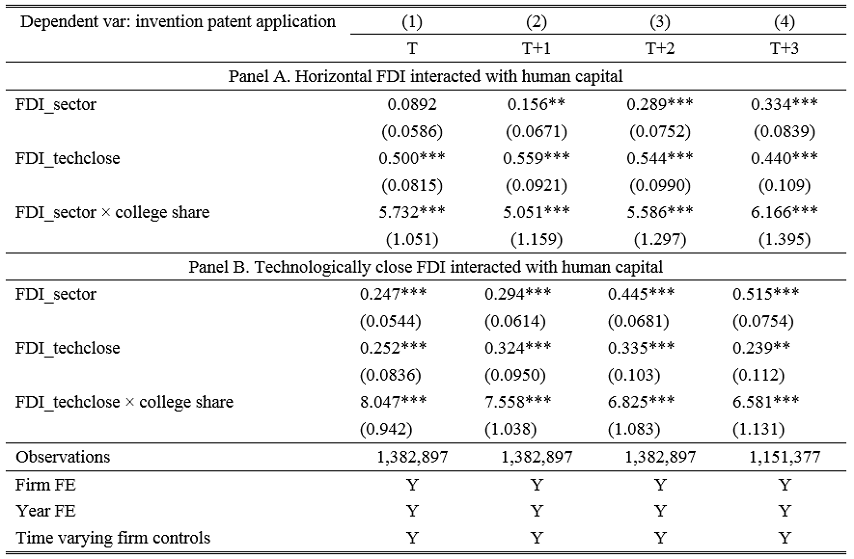

Finally, we explore the mechanism for such innovation spillovers. Domestic firms’ absorptive capacity and local human capital have proven critical in magnifying FDI spillovers. A unit increase in the interaction term of horizontal FDI and college population share results in a 5.7 to 6.2 % increase in invention patent application. A unit increase in the interaction term between technologically close FDI and college population share leads to a 6.6 to 8 % increase in invention patent application. In addition, we found that exposure to horizontal FDI in the same city has a negative effect on domestic firms’ innovation. Horizontal FDI from other cities generates large and increasing spillovers on domestic firms’ invention patent application. This suggests that the negative competition effect dominates in local market.

Table 2. IV results: local human capital

Taken together, our analysis provides evidence on dynamic innovation spillovers from FDI, highlights a novel channel for such spillovers through technologically close industries, and emphasizes absorptive capacity and human capital as key factors to maximize developmental benefits from FDI.

Note 1: Two industries are technologically close if they have largely overlapping technological domains. Detailed methodologies for measuring technologically close FDI is explained in Section 2.2 of the full paper.

(Yan Liu is an economist in the Finance, Competitiveness and Innovation Global Practice at the World Bank Group; Xuan Wang, University of Michigan.)

References

Aghion, Philippe, Nick Bloom, Richard Blundell, Rachel Griffith, and Peter Howitt. 2005. “Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120 (2): 701–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/120.2.701.

Alfaro, Laura, and Andres Rodríguez-Clare. 2004. “Multinationals and Linkages: Evidence from Latin America.” Economia 4 (2): 113–70.

Alfaro, L., Rodríguez-Clare, A., Hanson, G.H. and Bravo-Ortega, C., 2004. Multinationals and linkages: an empirical investigation [with Comments]. Economia, 4(2), pp.113-169.

Alfaro-Ureña, Alonso, Isabela Manelici, and Jose Pablo Vasquez Carvajal. 2019. “The Effects of Joining Multinational Supply Chains: New Evidence from Firm-to-Firm Linkages.” https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3376129.

Bai, Jie, Panle Jia Barwick, Shengmao Cao, and Shanjun Li. 2020. “Quid Pro Quo, Knowledge Spillover, and Industrial Quality Upgrading: Evidence from the Chinese Auto Industry.” NBER Working Paper No. 27644. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27644/w27644.pdf.

Fons-Rosen, Christian, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Bent E. Sorensen, Carolina Villegas-Sanchez, and Vadym Volosovych. 2017. “Foreign Investment and Domestic Productivity: Identifying Knowledge Spillovers and Competition Effects.” NBER Working Paper No. 23643. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23643.

Javorcik, Beata S. 2004. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers through Backward Linkages.” American Economic Review 94 (3): 605–27. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464605.

Javorcik, Beata S. 2008. “Can Survey Evidence Shed Light on Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment?” World Bank Research Observer 23 (2), 139–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkn006.

Javorcik, Beata S., and Mariana Spatareanu. 2009. “Tough Love: Do Czech Suppliers Learn from Their Relationships with Multinationals?” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 111 (4): 811–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2009.01591.x.

Zhang, Yan, Haiyang Li, Yu Li, and Li-An Zhou. 2010. “FDI Spillovers in an Emerging Market: The Role of Foreign Firms’ Country Origin Diversity and Domestic Firms’ Absorptive Capacity.” Strategic Management Journal 31 (9): 969–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.856.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email