Gaokao, Ability, and Occupation Choice

In China, the college entrance exam score is predictive for both firm success and wage-job success in the future, yet higher-score individuals are less likely to create firms.

In 2021, over 10.78 million Chinese high school students took the college entrance exam (Gaokao): a historical high. While the Gaokao is the most important talent selection channel in China, many questions about the Gaokao system remain unanswered. Does the exam measure ability? What type of ability? Does the exam score make a difference for a young person’s future career? Are higher-score individuals more likely to work in government, become entrepreneurs, or earn higher wages?

It is impossible to provide comprehensive answers to all of these questions in a single study, but here, we provide partial answers to some of these questions. Our results come from a recent study, motivated by a theoretical literature on talent allocation (e.g., Baumol 1990; Murphy, Shleifer and Vishny 1991; Acemoglu 1995). This literature has long noted that talent is general and can be used in both the entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial sectors, and that its allocation depends on the reward structure of a society. While this important theory of talent allocation has been developed for three decades, few empirical studies have directly tested it due to data challenges.

In Bai, Jia, Li and Wang (2021), we study whether talented Chinese are more or less likely to become entrepreneurs. Empirically, we link the universe of college admission records in 1999–2003 with the universe of Chinese firms and their owners, and then use a random sample of 20% of the linked data to examine who have become entrepreneurs and how successful their firms are. In total, this yields a sample of 1.8 million college graduates who created approximately 170,000 firms by 2015. We supplement this linked data with a large survey of Chinese college graduates that we conducted during 2010–2015 to study waged jobs. We use students’ Gaokao score as a proxy for talent and validate our measure with data.

Research design: within-college comparison

We focus on within-college analyses -- comparing individuals in their mid-30s with others in their cohort who graduated from the same college -- for conceptual and empirical reasons. Conceptually, the within-college comparison helps to control for the confounding factors of college reputation and network. Empirically, we find that most of the variation in firm creation comes from within colleges. For instance, although college fixed effects can explain up to 19% of the variation in wages of paid jobs (in our survey data), the effects can account for only 1.2% of the variation in firm creation. In addition, we find that the college fixed effects can explain only 46% of the variation in exam scores, leaving the majority of the variation to occur within colleges. The wide variation in scores within a college is driven by considerable uncertainty and political economy factors (particularly provincial quotas) in the college admission process. In addition, because Gaokao scores are comparable only for students from the same province and year, as well as the same academic track (social science vs. natural science), we isolate province-year-track fixed effects in our analyses.

We control for a set of individuals’ personal characteristics, which include gender, Hukou (rural vs. urban), high school quality, birth county’s GDP per capita, and age fixed effects. Although we do not have a specific measure of socioeconomic status (such as parental income), it is reasonable to assume that those from better high schools and wealthier counties have higher socioeconomic status. Within colleges, higher socioeconomic status is positively associated with exam scores.

Exam score, ability, and occupation choice

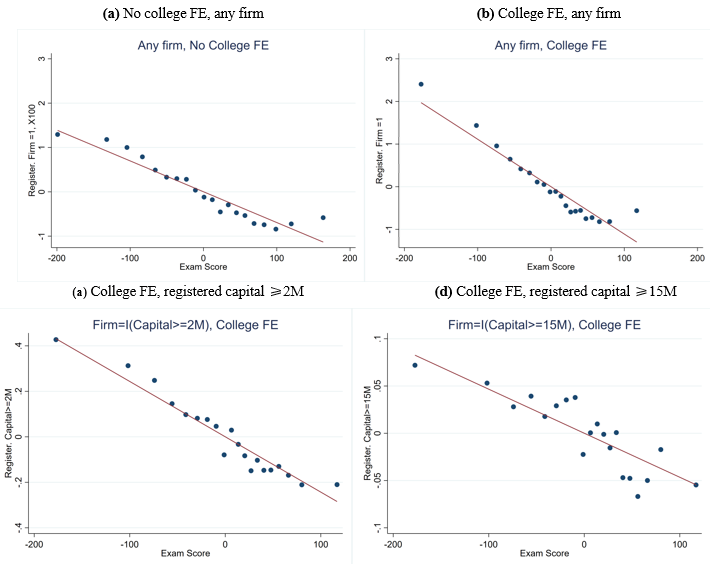

1. Given the same college, higher-score individuals are less likely to create firms by their mid-30s. A one-standard-deviation higher score is associated with a 10% lower probability of creating a firm. This finding holds even when we focus on the creation of more successful (large) firms, as shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: College Entrance Exam Score and Firm Creation

Notes: Firm=I(Capital≥2M/15M) refers to defining a firm only if it is large, i.e., its registered capital no less than RMB 2 million/15 million.

We also find that individuals of higher socioeconomic status are more likely to create firms. This finding suggests that it is difficult for socioeconomic status to explain the negative relationship between the score and firm creation.

2. Opposite to the entrepreneurship result, the firms that are created by higher-score individuals are more successful than those of their lower-score counterparts. The firms created by higher-score individuals are typically larger, more likely to expand, more likely to enter non-local markets, more likely to survive, and more likely to be publicly listed. These results hold even when we address potential entry bias by using within-college peer exposure to predict entry. These results suggest that talent, as measured by the Gaokao score, can be turned into entrepreneurial ability.

3. Outside of entrepreneurship, higher-score individuals also earn higher wages, obtain jobs that provide local Hukou, and are more likely to join the state sector. These findings imply that the Gaokao score is also positively associated with wage ability.

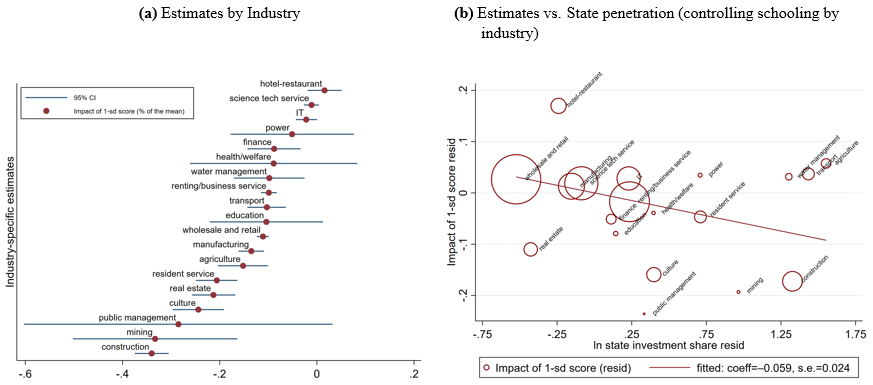

4. The negative score-entrepreneur correlation varies greatly by industries, according to state penetration (measured by the share of state investment in total investment by industry), Figure 2(a) plots the estimates by industry where the dependent variable is a dummy indicating entering a certain industry. The coefficients can be interpreted as “one standard deviation score is negatively associated with X% of the dependent variable”. We find wide variation across industries. For instance, the negative score-entrepreneur correlation in the construction industry is 15 times that in the IT industry.

Figure 2(b) plots the correlation between these estimates and state penetration, where we control for the influence of human capital (proxied by the average years of schooling of employees by industry). As shown, in industries with more state penetration, the negative relationship between the score and firm creation is stronger, which further illustrates the importance of the state in influencing career choices of talented individuals.

Figure 2: Score-Entrepreneur Relationships by Industry

Taken together, our results suggest that the Gaokao score is positively associated with both entrepreneurial ability and waged-job ability, but that higher-score individuals are attracted away by wage jobs, particularly those of the state sector.

Alternative hypotheses: Lower entrepreneurial ability? Personal traits?

In principle, however, there could exist two broad alternative hypotheses to explain why higher-score individuals are less likely to create firms. In the first alternative hypothesis, which we term the “lower entrepreneurial ability” hypothesis, the score does not measure a general talent that is useful for entrepreneurs; rather, it is negatively correlated with entrepreneurial ability, which could potentially explain the negative correlation between score and firm creation. For instance, one could assume that those with higher scores lack the skills of jack-of-all-trades (e.g., Lazear 2004) and/or that they obtain higher scores by putting more effort into the test, but their actual ability may be lower than that of their lower-score counterparts. Our evidence on firm success, however, goes against this hypothesis.

The second alternative hypothesis emphasizes that higher-score individuals possess unfavorable behavioral traits (e.g., more risk averse or less social) for becoming entrepreneurs, which we term the “personal traits” hypothesis. Using survey data, we find that, within any given college, higher-score individuals have a higher GPA and are more likely to receive academic awards. We do not, however, find strong correlations between scores and risk attitudes or participation in social activities. Overall, these results suggest that scores are not correlated with these behavioral traits in a way that is particularly unfavorable for becoming an entrepreneur.

Discussion

Can we apply our findings to other countries? In principle, one can link individual-level SAT (or other exam) scores to firm creation and firm success in the United States or other countries, however, we are not aware of any such studies. In light of our findings on the importance of the state sector, however, we conjecture that there may be wide variation across countries, depending on the role of the state in the economy. We thus hope that our study provides new avenues for future research that allow scholars to compare talent allocation across countries.

(Chong-En Bai, School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University; Ruixue Jia, University of California, San Diego, London School of Economics and Political Science and NBER; Hongbin Li, Stanford University; Xin Wang, Department of Economics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong.)

References

Acemoglu Acemoglu, Daron (1995), “Reward Structures and the Allocation of Talent,” European Economic Review, 39(1): 17–33.

Bai, Chong-En, Ruixue Jia, Hongbin Li, and Xin Wang (2021), “Entrepreneurial Reluctance: Talent and Firm Creation in China,” NBER Working Paper 28865.

Baumol, William J., Robert E. Litan, and Carl J. Schramm (2007), Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity. Yale University Press.

Lazear, Edward (2004), “Balanced Skills and Entrepreneurship,” American Economic Review, 94(2): 208–211.

Murphy, Kevin M., Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny (1991), “The Allocation of Talent: Implications for Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2): 503–530.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email